During the 1830s, a steamboat captain by the name of Henry Miller Shreve oversaw a Herculean feat of riverine clearing. A section of the Red River—which today forms much of the border between Oklahoma and Texas, and eventually empties into the Atchafalaya and the Gulf of Mexico—in northwest Louisiana had been clogged for roughly three quarters of a millennium by a tangle of logs, vegetation, and sediment known as the Great Raft. So Shreve took action: He won a contract with the Army Corps of Engineers, perfected the use of the snagboat, and after seven years finally rendered the river navigable. Today, Shreveport, Louisiana, is named in his honor, and the city has since given America many distinguished native sons, from Lead Belly to Terry Bradshaw (to Johnny Cochrane).

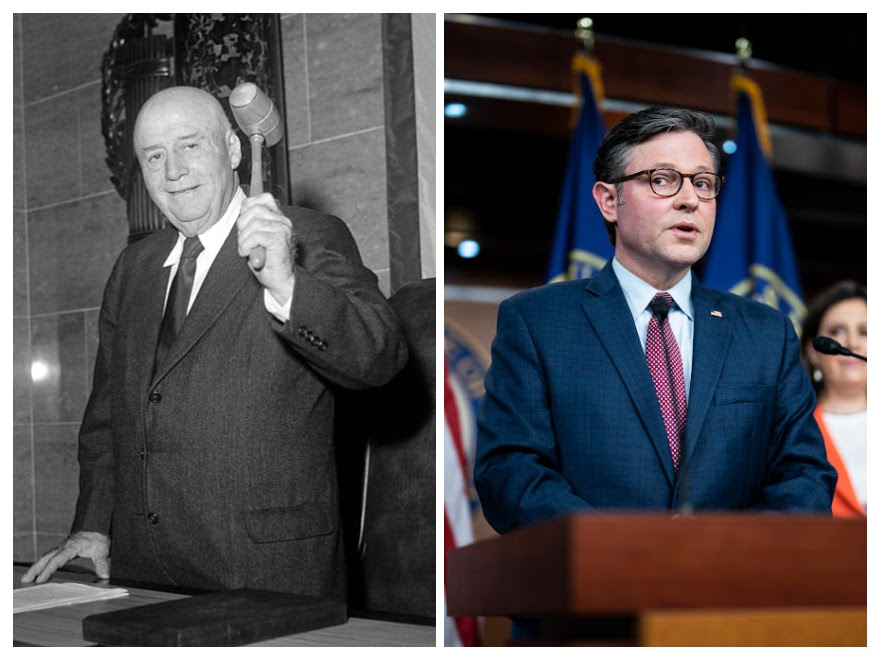

It’s also the birthplace of Speaker of the House Mike Johnson.

Since winning the gavel last October, Johnson has faced the same pressures that led to his predecessor’s ousting: crafting a spending deal palatable to uncompromising members of his conference. He seems to be repeating Kevin McCarthy’s approach so far, cutting deals that satisfy most Democrats and Republicans before moving them to the House floor via suspension of the rules—a tool traditionally reserved for less important legislation. That’s how the House passed a continuing resolution in November, the National Defense Authorization Act in December, and another continuing resolution earlier this month. Johnson most recently made a deal with Democrats on full-year spending levels, and the corresponding spending bills will almost certainly pass using the same procedures.

But these are bipartisan deals with broad bipartisan support—and that means they’re total failures by the lights of the House Freedom Caucus, which has denounced every one of them for compromising on conservative values. Johnson, apparently guilty of the same sins as McCarthy, may soon find himself facing the same circular firing squad.

There are no obvious solutions to Johnson’s problems, no Shrevian snagboats to clear the way for a bill that 217 House Republicans, 60 senators, and President Joe Biden all want signed into law. Physical obstacles may yield to ingenious devices, but political problems must be worked out through political means.

Mired as this Congress has been in seemingly endless budget negotiations, we might hope that Johnson can channel Shreve’s river-opening spirit. But if the speaker is searching for historical forebears to guide him, he would do well to look some 200 miles upriver, from Shreveport to the Denison Dam, located on the border between Oklahoma and Texas.

A different kind of speaker.

It was built in the early 1940s thanks largely to the political clout of Samuel Taliaferro Rayburn.

Originally from nearby Bonham, Texas, Rayburn was known as an unflaggingly loyal, straight-talking, good-to-his-word legislator. He rose through the ranks at the Texas legislature, becoming speaker there at age 29, and in 1912 he successfully ran for the House of Representatives as a Democrat. Rayburn spent five decades in Congress where, among other legislative achievements, he built a coalition for rural electrification that made the Denison Dam a reality. And for 17 years, he served as 43rd speaker of the House.

Rayburn’s unpretentious persona has much to offer to Johnson, who in accepting the speakership said he wants his office “to be known for trust, and transparency, and accountability.” That was certainly Rayburn’s way.

His meteoric rise in the Texas state legislature had much to do with his dogged unwillingness to abandon two scandal-embroiled leaders who came before him. Once he became speaker in Austin, a fellow legislator described him as “quick to rule, accurate, honest and sincere. He is fair to every member and is universally popular. You always know where to find him.” That reputation followed him to Washington. As Rayburn’s biographers D.B. Hardeman and Donald C. Bacon wrote of him (and his mentor, fellow Texan John Nance Garner): “The credo of the southwestern frontier was their code—tell the truth, let your word be your bond, love your country, stand by your friends.”

Rayburn put in many long years as an effective backroom operator, including during Democrats’ decade in the minority, before becoming a powerful champion of New Deal legislation as the chairman of the House Commerce Committee. Having earned his colleagues’ trust, he was able to act as a broker between the many different factions in the House, even in times of narrow Democratic majorities. Bringing together bipartisan governing coalitions often required sanding off bills’ sharp edges, thereby disappointing crusading advocates. In handling a vicious fight over public utility holding companies in 1935, for example, Rayburn skillfully guided Congress toward a compromise that failed to deliver the deathblow to the corporate form that many (including he himself) had hoped for, but nevertheless secured strong regulation.

Rayburn also understood that politics is fundamentally about accommodation rather than running one’s competitors off the field. After FDR’s disastrous court-packing failure in 1937 empowered conservatives, then-House Majority Leader Rayburn convinced the White House to reduce its lobbying efforts on Capitol Hill. Instead, he would figure out how to work with his conservative colleagues rather than dominate them. “I used to want to be a big, tall fellow, but I found I can dart in and out and between ’em and get things done before they see me,” Rayburn declared. That didn’t mean he was any sort of pushover, though. When Time magazine called him a great compromiser, he retorted, “I am not a compromiser. I’d rather be known as a persuader. I try to compromise by getting people to think my way.”

Of course Mr. Sam, as he came to be known, was able to operate out of the public eye to a degree difficult to imagine in the age of social media. In his basement office, over brown liquor, members exchanged information and opinions with total candor and an expectation that everything said was “strictly graveyard.” With fewer staff and media around, the House in Rayburn’s day was based more on human relationships between members. One could rise to the top in that environment only through great longevity. Rayburn first took office in the House in 1913, at age 30; it took him 27 years, and a whole lot of informal institution-building with himself at the center, to climb the leadership ladder and finally become speaker.

Mike Johnson’s legislative logjam.

Johnson, by contrast, must lead after less than seven years of House service and no time at all in top leadership. He has to somehow build relationships amid a nonstop media circus and as professional partisans portray him as an extreme ideologue. Members of the Republican conference seem to believe that he can implement a more open process, giving all members a greater chance to participate while simultaneously delivering solid partisan victories at every turn. That combination is likely impossible, which means Johnson has an unenviably difficult job.

But if he can make his House a bit more like Rayburn’s, one might begin to make out the shape of a successful speakership. For all of Rayburn’s stature, nobody ever expected him to be a dictator. Rather, he made it clear that everyone would get a fair shake in having their view considered, and that the body’s majority would work its will. He was known to help committee chairmen shepherd their bills to the floor, fending off last-minute attacks, even on bills he did not support himself.

There are some reasons to be hopeful—and they have to do with Johnson’s similarities to Rayburn. Kevin McCarthy portrayed himself as a genial dealmaker, ready to pal around with anyone and quick with a joke. For all those smiles, though, too many of the former speaker’s colleagues felt that he talked out of both sides of his mouth. Ultimately, he lacked the trust needed to act as a good faith broker between factions. Johnson, on the other hand, exudes earnestness and preaches straight-shooting, much as the young Rayburn did. He’s surely a committed ideologue, and yet Johnson has gained his colleagues’ esteem by presenting himself as a real coalition-builder, someone willing to humbly hear out anyone in search of the common good.

That self-presentation is more promise than solid record, but it creates an opportunity for Johnson. Rather than trying to be a Republican Nancy Pelosi, he could follow Rayburn’s example and prioritize coalition-building and legislating over the mere pursuit of partisan angles.

Take the supplemental spending bill Congress is currently debating. In a recent piece, Politico reporter Rachel Bade explored how a Johnson speakership could prioritize legislating—while also reminding readers, over and over, why most Capitol Hill veterans doubt that will be the case. Yes, Johnson has relied on bipartisan majorities and suspension of the rules, but he’s done so solely for must-pass bills. The supplemental spending bill—which attempts to package Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan aid with more resources for securing the southern border—is different. It doesn’t absolutely have to pass, and plenty of Republicans have expressly declared a desire to see it fail.

Johnson might choose to put whatever deal the Senate delivers up for a vote, again using suspension of the rules. That seems like the quickest way to passage, and it would please many Democrats who believe in the importance of passing the bill quickly. But it very well could reignite the intraparty conflagration that consumed McCarthy. Perhaps Johnson would survive it; Bade floats the possibility that his straight-dealing might earn Johnson some Democratic support that McCarthy never got. But it’s hard to overstate how angry many Republicans would be in this scenario. They would insist, and not unreasonably, that there should have been extended, substantive deliberation, rather than a quick vote that deprives opponents of all their parliamentary resources.

Speaker Johnson could alternatively try to make his colleagues shoulder the burden of shaping this compromise. There is a sense of urgency but no hard deadline. Bringing conservative Republicans into the debate, giving them a chance to air out their concerns, and ensuring that some of their most important demands are incorporated into a final bill, would go a long way toward creating the kind of broad coalition needed to make progress on border security or foreign aid. The speaker ought to say: “It’s not my job to figure everything out, but to help make sure that the House can do so.”

In other words, Johnson needs to remind everyone, loudly and frequently, that he has no Shrevian snagboats capable of forcing GOP-only legislation through the impasse of divided government. What he can do is facilitate real deliberation, followed by a real chance for a (bipartisan) majority of the House to work its will.

Taking this approach will earn Johnson some harsh critics, especially among those who would rather see an intractable logjam than any governing decisions they dislike, so great is their desire to deprive Biden of any accomplishment this election year. Perhaps that would include former president Donald Trump.

Nevertheless, it would be the right course. As a defense, Speaker Johnson should take to heart a Rayburn aphorism: “Any jackass can kick a barn down, but it takes a good carpenter to build one.” Building coalitions is the essence of congressional politics; it’s the key to keeping legislative currents flowing. The politics of 2024, sure to be full of darker notes, could use someone who understands that.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.