DES MOINES—It all started out like a typical Iowa caucus. Gathered around the gleaming basketball court at Drake University’s Knapp Center, the caucus goers of Des Moines 62nd precinct—the city’s largest—found themselves pretty evenly split. Elizabeth Warren had the strongest support, but all four of the other major candidates, including Bernie Sanders, Joe Biden, Pete Buttigieg, and Amy Klobuchar, had managed to stay above the 15 percent support benchmark needed to be considered “viable.” Sanders’ supporters looked in danger of missing the cutoff—until two of the dozen-odd voters who were there to support Tom Steyer wandered over to the Bernie group just before the first count was made.

Down the street, at the Drake Fieldhouse, things were getting complicated for the 38th precinct, which is largely comprised of the undergrads of Drake University itself. As the caucus groups formed up on the building’s artificial turf, it quickly became clear that Klobuchar’s and Biden’s supporters would not reach the viability threshold, and the Warren, Sanders, and Buttigieg camps began sending emissaries around to try to lure the disenfranchised participants to their own groups. Instead of filtering into the other factions, however, the Klobuchar and Biden supporters struck a deal: Along with the handful of Andrew Yang fans at the caucus, they would form a new joint faction. The man they agreed to throw their support behind? Sen. Cory Booker, who dropped out of the race in January. Klobuchar’s precinct captain told me the idea was to demonstrate that, while none of their candidates registered on their own, there was still plenty of enthusiasm for a moderate candidate at the caucus. Their combined forces were enough to deny a delegate to Sanders, whose supporters were far from pleased at the stunt.

Across town at First Presbyterian Church, Sanders supporters were left crying foul after supporters of the other campaigns worked together to ensure Biden, Warren, and Klobuchar would all be viable at the second ballot, resulting in a single delegate being awarded to each candidate despite Bernie having the most supporters at the caucus by far.

Out in the suburbs of West Des Moines, where Sen. Amy Klobuchar had stopped by a pair of caucuses taking place at Johnston Middle School to speak just an hour earlier, her campaign was still a few votes short of viability. Here, again, it was Steyer supporters who came to the rescue: One woman agreed to caucus for Klobuchar even though, she told a reporter, she wasn’t her first or second choice.

The Iowa caucuses are always a constellation of more than 1,600 little vignettes like these, hundreds of tiny political intrigues which in sum give the country its first sense of who has real momentum behind them going into the next early voting states of New Hampshire and Nevada. This morning, however, the vignettes are all we have: The sum is still just as much a mystery as it was at the second caucuses closed last night.

An app the state party had instructed caucus officials to use to report caucus results reportedly malfunctioned, forcing those officials to make use of a backup phone line system. The unexpected stress on that system left officials on hold for extended periods as the night stretched on. Many simply gave up and went to bed, saying they’d call the results in Tuesday. Cable news networks, which had worked themselves into a lather throughout the day Monday, were suddenly left with an unexpected famine of information and a whole lot of empty airtime to fill.

“You’ve got interviewers interviewing interviewers,” one Iowan at the Des Moines airport chuckled to a friend as CNN blared on the TV overhead. “They don’t have anything to say! No news!”

The strange fact of the matter is that none of the caucus results are unknown, exactly: Unlike in a primary, the results of each individual caucus are announced before caucusgoers go home at the end of the night. Each piece of the Iowa results, then, is known to some small group of Iowa Democrats or other—the rub is just in assembling all that information into something a candidate can carry into New Hampshire.

Some anecdotal evidence can give a vague sense of what happened on Monday, of course. The general consensus Monday night appeared to be that things looked grimmer than expected for Joe Biden, who failed to meet the viability threshold in a number of districts where he expected to be competitive. If that holds true, Biden is far from dead in the water—he still holds a polling lead nationwide and a commanding one in Southern states. But a poor showing in Iowa would mean he has failed to cut off any of his upstart challengers off at the knees early, and that Amy Klobuchar and Pete Buttigieg are likely to stick around for some time to come.

For the most part, candidates were forced to spend Monday night doing something unusual for an election night, yet perfectly appropriate to our fragmentary political age: rolling out a version of their victory speeches despite no news of victory, trying to build their own New Hampshire momentum out of pure spin. No candidate leaned into this more shamelessly than Pete Buttigieg.

In fairness, Buttigieg really, really needed a win in Iowa to keep his campaign chugging along. Yet it was a bizarre sight to see him go into full triumphalist mode at his campaign party before a single precinct had been officially counted.

“Tonight, an improbable hope became an undeniable reality,” Buttigieg told his supporters in Des Moines. “We don’t know all the results, but we know by the time it’s all said and done—Iowa, you have shocked the nation. Because by all indications, we are going on to New Hampshire victorious.”

The Warren and Sanders camps were more measured, with each campaign suggesting its internal metrics showed strong numbers in Iowa. Sanders’s team in particular claimed that its numbers showed a tight race between Bernie, Warren, and Buttigieg, with Biden in a distant fourth. And Amy Klobuchar, without making any concrete claims about how the numbers would shake out, enthused to her supporters that they were “punching above our weight.”

The debacle is a horror show for Iowa, which prizes both its unusual caucus system and its first-in-the-nation role in the primaries. Both are already coming under intense scrutiny from incensed Democrats, who can’t believe the results were this badly botched. Their ire has been aggravated by their opponents’ nonstop gloating: Trump’s campaign manager, Brad Parscale, and his sons Don Jr. and Eric all spent Monday night wildly speculating that Democratic officials were fixing the results, and the president tweeted Tuesday morning that “The Democrat Caucus is an unmitigated disaster… just like they ran the Country.”

Still, it’s hard to look at Monday’s results and not feel a suspicion that all the confusion and chaos is weirdly appropriate. In a race where five candidates are all still likely to be viable coming out of Iowa, where nobody has been able to open a truly commanding lead over his or competitors, where a thousand theories of the election bounce off one another and intermingle with no real way of sussing out yet which is right and which is crazy—Monday’s botched result probably gave a better sense of where the race currently stands than any concrete outcome could have done.

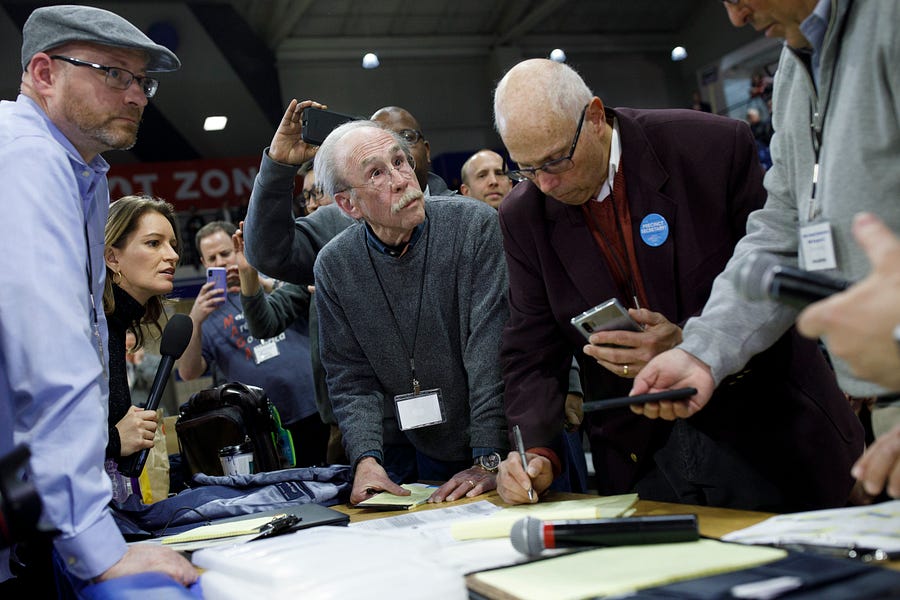

Photograph of caucus officials looking at a vote count at Drake University by Tom Brenner/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.