We have all had the unsettling feeling that our smartphones are reading our mind. You Google “sandwich places near me,” and then five minutes later you get a Facebook ad for Panera or Subway. Your phone isn’t reading your mind, but neither is it a coincidence.

Beginning this week, iPhone users should be able to exert a little more control over the data that app makers utilize to make those personalized ads and notifications show up. Apple is introducing new privacy measures that would, in theory, give customers control over whether they give their data away or not, and if they do, knowledge of what type of data they are handing over to companies.

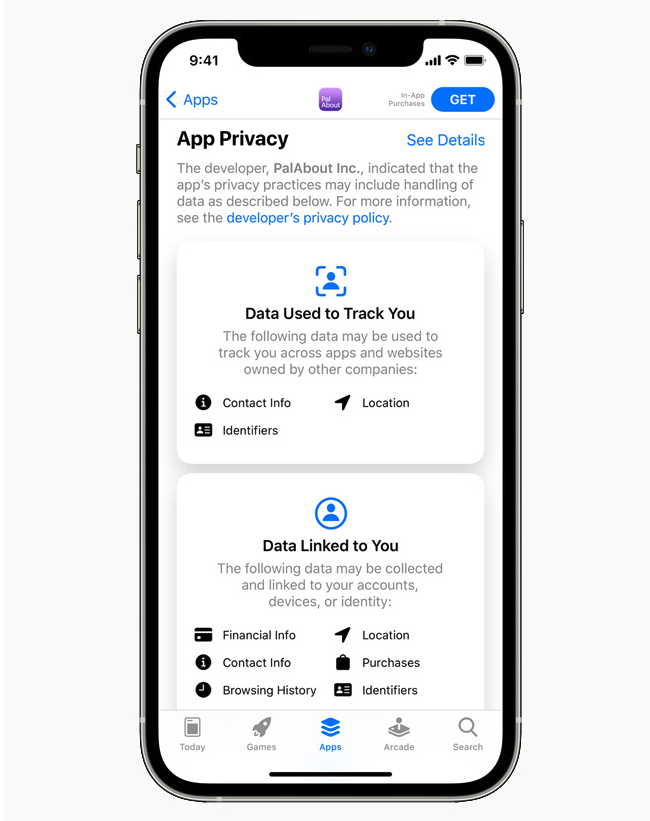

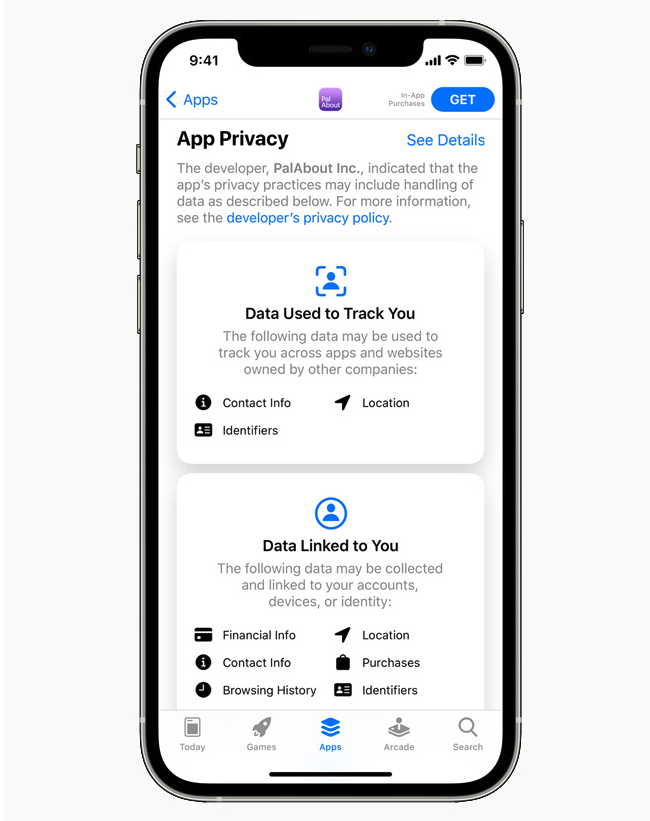

With the introduction of iOS14 in June 2020, Apple introduced a “privacy nutrition label” for all apps. Every application in the App Store, even those made by Apple, is required to summarize what that app is doing with your data. These labels (seen below) show two things: the data the app uses to track you and the data that is linked to your identity in the eyes of advertisers. These labels are seen on the landing page of apps available in the App Store.

Some apps hoover up even more of your data than your financial information or location. Both Instagram and YouTube have access to your search history, your browsing history, “sensitive info” and “other data.” There’s a common saying about social media and free apps that “if you’re not the customer, you’re the product.” And we are all lucrative products. The average American adult’s data is worth about $4.91 per month, according to a study published in Strategy+Business magazine. That may not seem like much, but over the average person’s lifetime, that’s a lot of data and a lot of money. Overall, the data economy has been valued at $227 billion and is expected to reach $400 billion by 2025.

Apple’s “privacy nutrition label” lets users know what kind of data they are giving away. Its new policy, expected to roll out this week, should let people control what they share. The “Apple Tracking Transparency” feature will, according to Apple, “require apps to get the user’s permission before tracking their data across apps or websites owned by other companies.” Apple users can expect to see notifications that look a lot like the one below, asking user’s permission to share their data.

Typically, developers can track a user’s activity across a wide range of websites to then personalize ads they display on their app. That’s why, if you spend a few minutes browsing for the best deal on a new coffee pot, you’re likely to start seeing ads for a new Keurig or Breville on your next social media scroll.

App developers pay digital advertising platforms to auction off available ad space in the apps. Under “Settings,” Apple users will be able to see which apps have asked to track them and choose whether or not they want certain apps to track their online activity. Users will have the ability to opt-in to practices typically used by app developers, rather than having to opt-out.

Privacy experts see these moves by Apple as a step in the right direction, but far from the last step in protecting consumers’ data. “This is all great news,” Dr. Lorrie Cranor, the director of the CyLab Usable Privacy and Security Laboratory at Carnegie Mellon University, told The Dispatch. “We have to start somewhere, and I think this is great. Hopefully it’s not the end, though. Hopefully it’s just the beginning.”

The privacy protections have some limitations, though.

A lack of enforcement mechanisms from Apple is cause for some skepticism among pro-privacy advocates. The “nutrition labels” are self-reported, according to Apple—raising questions about accuracy. With the new tracking transparency system, app developers are required to “respect your choice” of not being tracked. If they don’t, Apple says it has the right to remove the app from the App Store. Still, that may not be enough.

“I do think that Apple could do some policing. Some of these things, they cannot be automatically detected, but there’s actually a lot in there that Apple could automatically detect whether it’s consistent with what the app is doing, and I would like to see them do that,” Cranor said.

App developers have varying perspectives on the new user protections. Some view the move as a welcome change, while others see it as a cumbersome annoyance.

Protecting consumer privacy is becoming more and more important to app developers, and is seen as a “feature of business,” according to Ashley Durkin-Rixey, a spokesperson for the App Association, a lobbying group for app makers and connected device companies. Developers “see this as a way to indicate to consumers: ‘Here’s what we’re doing,’” she told The Dispatch. “For many of them, this is a way to compete. And especially a way to compete against bigger apps.”

Some companies worry the Tracking Transparency feature will affect their bottom line and make it harder to measure the effectiveness of an ad. Durkin-Rixey said it’s clear why some developers are worried: “It makes it a little harder to track your effectiveness. Right now, it’s really easy to open Facebook and see what your effectiveness is on an ad.”

But she added that she expects companies to be able to adapt to the changes.

Facebook derives most of its revenue from digital advertising and initially said the new privacy protections could significantly hurt its earnings. The company said in a blog post back in August 2020 that the changes to Apple’s policies may cut its audience network revenue by 50 percent or worse: “In reality, the impact to Audience Network on iOS 14 may be much more, so we are working on short-and long-term strategies to support publishers through these changes.”

Since then, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg reversed the company’s initial gloomy look at the changes, saying on a Clubhouse forum called “PressClub with Josh Constine” that it might actually bring more business to Facebook “if Apple’s changes encourage more businesses to conduct commerce on our platforms, by making it harder for them to basically use their data in order to find the customers that would want to use their products outside of our platforms.”

However, Zuckerberg added he’s worried how these changes will impact the small businesses and developers that use Facebook’s advertising tools: “I think that there is going to just be a lot of issues there that I’m quite worried about for the health of a lot of the businesses that we try to work with.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.