A video making the rounds on Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube claims that Bayer, the German pharmaceutical company, was involved in deadly medical testing on Auschwitz prisoners during the Holocaust.

The clip is pulled from the beginning of a December episode of the Joe Rogan Experience podcast featuring guest Brigham Buhler—founder of the virtual health care provider Ways2Well. Buhler, a critic of what he calls the “medical industrial complex,” referenced Bayer’s links to medical experimentation during World War II in a discussion with host Joe Rogan about profiteering and the stifling of innovation in the medical industry.

According to Buhler, a small medical company—later identified by Buhler as a precursor to pharmaceutical giant Bayer—reached out to the Third Reich during World War II asking for 150 participants for a clinical trial, upon which the regime shipped 150 healthy Jewish women for product testing. Buhler claims that the company explained in letters to the Third Reich that all 150 women died within six months and asked for more participants to be sent.

The specific example referenced by Buhler has been alleged for decades, though Holocaust historians and other researchers have never found corroborating evidence to support it. But the precursor company to Bayer did in fact work closely with Nazi officials during World War II and facilitated a number of atrocities.

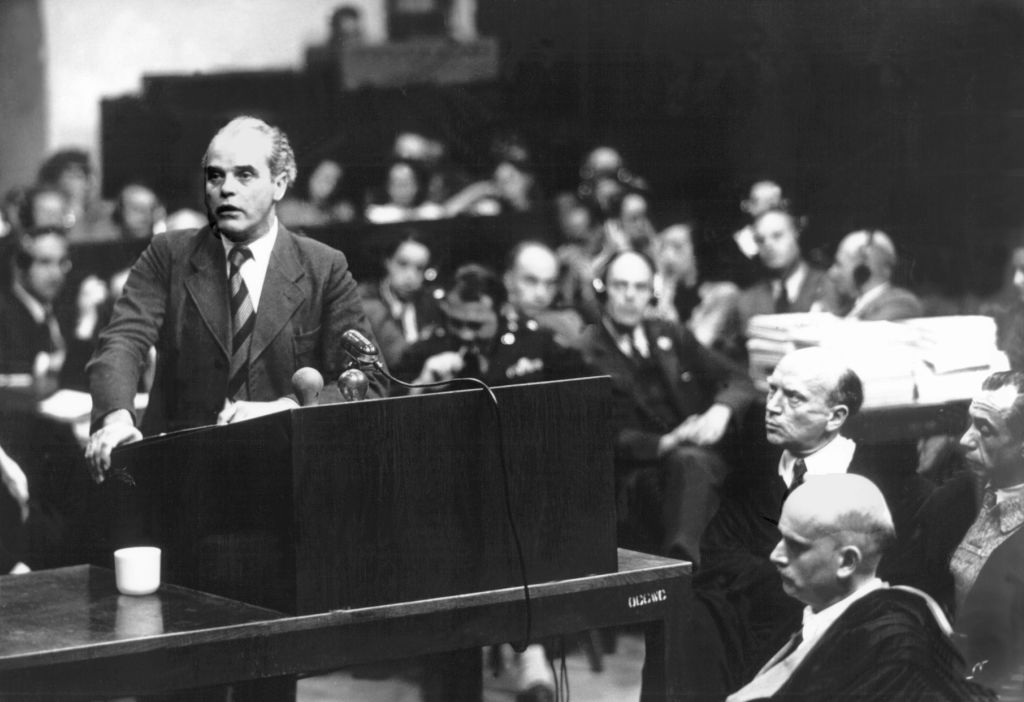

The claim to which Buhler referred initially emerged in court in 1947 as part of the sixth Subsequent Nuremberg Proceedings—The United States of America vs. Carl Krauch, et al.—against members of the German chemical pharmaceutical conglomerate I.G. Farben, the precursor to Bayer. According to research into the story by a team of anesthesiologists and historians, an affidavit given in the case by a survivor of the Auschwitz concentration camp claimed that a Soviet officer had requested the translation of five letters that showed correspondence between I.G. Farben and the commander of Auschwitz. The letters supposedly detailed the sale of about 150 women for use in experiments for a new soporific (anesthetic) drug. In 2019, this team, curious to see if they could confirm the use of female prisoners to test a drug used in further anesthetic practice, conducted research to determine whether any corroborating evidence existed for the sale. The team investigated the Auschwitz archives, Bayer corporate history and archives, and former Soviet Union archives, but no corroborating records could be found.

“We did not find in the investigated places any proof of this purchase,” Dr. Claude Lentschener, an anesthesiologist at Paris’ Cochin Hospital and the lead author of the study, told The Dispatch Fact Check. “At the present time there is not any known proof of this affair.”

Dr. Piotr Setkiewicz, director of the Centre for Research at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, expressed similar reservations about the story. “I believe that the testimony cited by some other historians is unconfirmed and, considering the circumstances of the event, unlikely,” he told The Dispatch Fact Check. “However, there is no doubt that Bayer ordered its new experimental drugs to be tested on Auschwitz prisoners through the camp doctor SS-Obersturmfuehrer Helmuth Vetter.”

Bayer itself is quite open about its predecessor’s involvement with the Nazi regime. “I.G. Farben was directly involved in many of the National Socialist injustices,” a representative of Bayer’s Finkelstein Foundation told The Dispatch Fact Check in an email. “This includes war production, intensive use of forced laborers at its former Lower Rhine sites and use of forced laborers at Auschwitz-Monowitz for the construction of the Monowitz factory.”

I.G. Farben was originally formed in 1925 from the merger of Bayer and five other German companies, and by the onset of World War II was central to Germany’s war production effort. The company relied heavily on forced labor in occupied territories beginning in 1940, and in 1941 constructed a chemical factory near Auschwitz to produce a form of synthetic rubber. In 1942, I.G. Farben began building its own concentration camp, Buna-Monowitz, to accommodate additional workers. This camp relied on both Allied prisoners of war and laborers from Auschwitz. Upon Germany’s surrender in 1945, I.G. Farben was dissolved and 23 of its senior managers were put on trial in Nuremberg. The modern Bayer company was formed in 1951.

Bayer has openly acknowledged its historical ties to the Third Reich, and the company has pursued a number of initiatives to explore and document its involvement in Nazi atrocities. In 2023, the company established the Hans and Berthold Finkelstein Foundation—named after an employee of I.G. Farben who was expelled from the company due to his Jewish heritage and his son, a forced laborer in the camps—in order to “remember the past and to reflect on the deeds of I.G. Farben during National Socialism.” The foundation’s mission is built on three pillars—remembrance, research, and resistance—and seeks to both shed light on the history of I.G. Farben while fighting antisemitism, racism, and totalitarianism in the present day.

“As a responsible global player, we owe it to the victims and their descendants to face up to our history and learn specific lessons,” the Finkelstein Foundation representative said. “We cannot undo past injustices, but we understand that there remains a historical and moral responsibility for the repercussions, and we are committed to that responsibility.”

If you have a claim you would like to see us fact check, please send us an email at factcheck@thedispatch.com. If you would like to suggest a correction to this piece or any other Dispatch article, please email corrections@thedispatch.com.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.