For too long, our debates on post-secondary education have taken a binary form: either “college for everyone” or “learn a trade.” But in an era when career trajectories are no longer linear, and when technology is rapidly and unpredictably evolving, the ability to adapt and acquire new skills is essential. What we need instead is a “both-and” approach.

Ben Wildavsky, a visiting scholar at the University of Virginia’s School of Education and Human Development, puts adaptability front and center in his recent book The Career Arts. In doing so, he helps to fight back against the false dichotomies that riddle discussions about post-secondary education.

The most important thing to remember about the benefits and costs of college education is that national wealth is directly related to levels of education and skills. This was true in the transition from agriculture to manufacturing (via the universal high school movement) and from manufacturing to a more service-based economy. Since the 1970s, America has invested massively in expanding access to higher education and reaped the benefits in terms of higher GDP and living standards. Education, then, feeds human capital development, the complex mix of education, skills, and social connection on which free markets depend for growth. To paraphrase Lincoln, human capacity is the underlying source of all capital.

A recent report we wrote at the American Enterprise Institute on the value of a bachelor’s degree supports this insight. People with four-year degrees make far more and tend to accrue much more wealth than those with only a high school education or a two-year degree. They also enjoy higher rates of marriage and better social and health outcomes. What’s true at the individual level is also true at the community level: Regions with higher concentrations of people with four-year degrees are wealthier and healthier. They also have a much easier time attracting investment, driving further economic growth. Education and human capital are the ignition points for the kinds of virtuous cycles we seek for ourselves, our children, and the towns and cities we live in.

Higher education has been an unalloyed good for the economy and human well-being. But we’ve reached a point of diminishing returns. The rapid escalation in tuition and fees has cut into the earning and wealth premiums that previous generations enjoyed. Further, as economist Bryan Caplan has pointed out, the value of a degree is back-loaded, with almost all of the economic returns concentrated in the final year of education. This is likely because degrees “signal” to employers that an applicant is more likely to have the types of skills necessary for workforce success.

This brings us to The Career Arts, in which Wildavsky makes an argument that will satisfy no one: He says career success requires integrating broad-based skills (like those acquired through a liberal arts education) with more narrow, technical skills (such as those acquired through credential programs through community colleges, technical schools, and apprenticeship programs) rather than choosing between them. Integrating them, Wildavsky says, supports well-rounded and resilient workers who can readily adapt to changing technological and economic conditions. According to economist Nouriel Roubini, this integration is becoming increasingly valuable as technology advances.

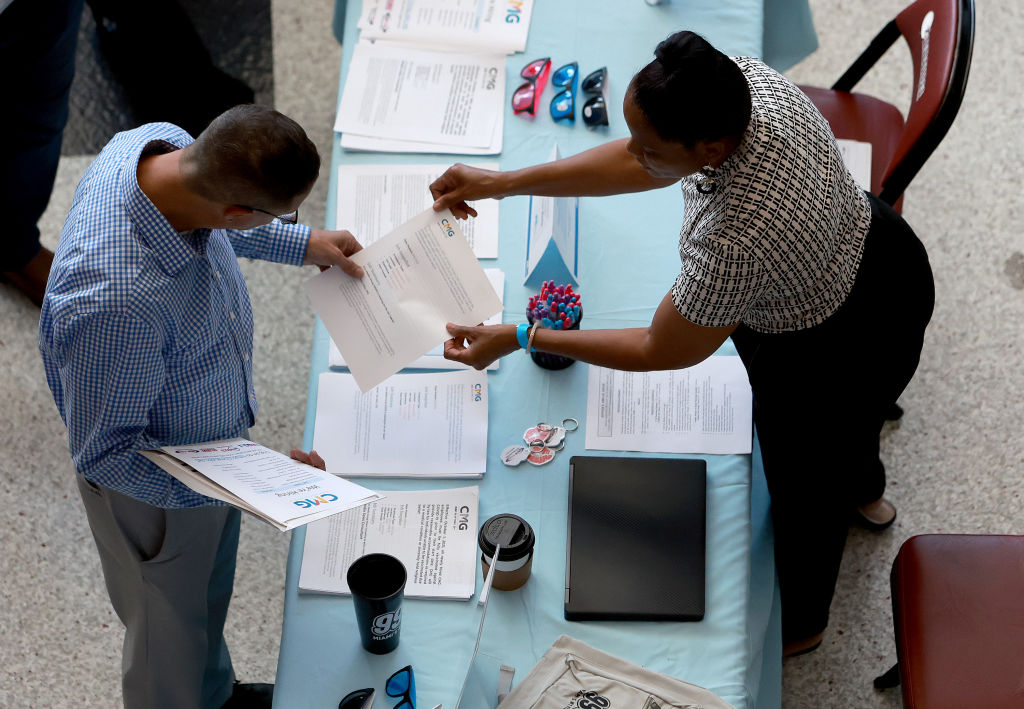

As Wildavsky points out, rising tuition has led to a pivot toward non-college, and thus cheaper, forms of education and credentialing. Wildavsky maintains that these alternatives should play an important role. For those who lack interest or ability to pursue a degree, alternative post-secondary pathways may be the best way to build up skills. Sector-based employment programs such as Year Up and Per Scholas, which train workers for jobs in particular industries, may be a particularly good option: These programs have demonstrated strong long-term employment and wage outcomes.

But Wildavsky contends that an exclusive emphasis on shorter-term credentials is misguided. Many of these credential programs don’t appear to deliver improved earnings or career prospects, especially for disadvantaged black and Latino learners. In fact, they risk becoming a “second-class route” that fails to equip these workers with the skills that can help them access some of the best jobs in the American economy, anthropology-degree-barista anecdotes notwithstanding.

Another problem with non-degree credentials is that whatever near-term advantages they confer in terms of employability tend to be offset by “skills obsolescence.” The narrower the specialty, the more vulnerable it is to shifts in technology and the general trend toward automation. In contrast, the broad, flexible skills developed during a four-year education let workers stay ahead or at least keep pace with shifting economic demands.

Wildavsky is right to argue for a “both-and” approach. High-quality credential programs should complement, not replace, a college education. As he notes, a 2021 survey found that adults with both a college degree and a non-degree credential were more likely than those with just a degree to report that their education was worth the cost, made them attractive job candidates, and helped them achieve their goals.

Another key element in Wildavsky’s career success formula is social capital. This refers to the networks of relationships that help us thrive psychologically, socially, and materially. Higher levels of education have long been associated with increased trust in others and greater participation in the relationships that create so-called “weak ties”—the “friend of a friend” connections that are critical to career advancement. If students pursue non-degree options, they should purposefully build social networks, through civic and social institutions and social clubs or through credential programs themselves. For their part, credentialing institutions need to be deliberate about helping their students acquire and integrate social connections into their career planning.

If there’s a blind spot in Wildavsky’s analysis, it relates to improving the ways in which we support students (and workers) facing decisions about education, training, and careers. For the average person, the array of education and training options is effectively infinite, while the resources we devote to helping people sort through these options is finite in the extreme. Faced with this smorgasbord, we tend to fall back on strictly economic factors to make decisions.

One survey found that 93 percent of American parents want their child to major in engineering. Engineering is indeed one of the most lucrative careers, but the reality is that very few people are intellectually equipped to become engineers. Too often, families are simply flying blind—and not only when it comes to choosing between educational options. Often, they haven’t even had an honest conversation with their children about their interests and abilities. Those attributes are the “horse”; schools and programs are the cart. It’s crucial to get them in the right order.

Shifting this conversation requires creating a more personalized, nuanced understanding of post-secondary options and outcomes. Through more conversations between students and their parents, and more robust college and career counseling services in high schools, we can better support students, whether they are high school seniors or midcareer workers trying to adapt to a changing market. In particular, we can help students decide, based on their unique skills, interests, and financial situations, what postsecondary route is best for them, whether it’s a four-year college, a community college, a trade school or technical program, or directly entering the labor market.

We do a disservice to students when we pretend that they can make decisions about what’s best for them by relying solely on studies and data. A more nuanced message is needed, one that is informed by population-level data about the merits of different pathways but which is also sensitive to an individual’s circumstances. Once we combine this message with a “both-and” approach to postsecondary education, such as Wildavsky’s, we can offer students and workers an empowering message, one that calls on them to take the helm of their own futures.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.