In an extremely competitive field, Hamline University is making a bold bid to be the new standard-bearer for universities willing to cast aside principles of academic freedom and freedom of speech. What really sets Hamline apart is the degree to which the university is sacrificing its core academic mission for the sake of political correctness and the willingness of the university president to be so explicit about what she is doing.

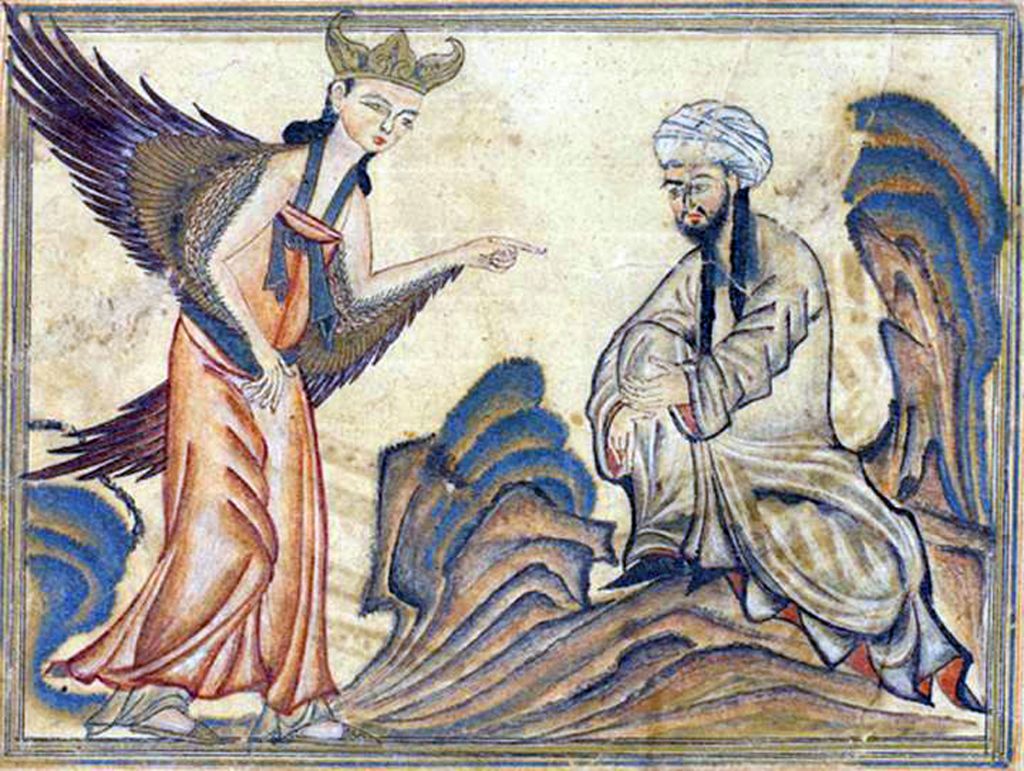

Hamline is a private liberal arts college in Minnesota. During the fall semester of 2022, an adjunct instructor for an undergraduate class in global art history showed the students a famed medieval work of Persian art. The painting depicts the Prophet Mohammed receiving the revelation of the Quran from the Angel Gabriel. The class session was virtual and recorded. Given that many Muslims believe that creating or viewing images of Mohammed is forbidden, the instructor spent some time explaining the works about to be shown and gave students an opportunity to turn off their video. Nonetheless, a student in the class also happened to be the president of the Muslim Student Association, and she complained, “I’m like, ‘this can’t be real. As a Muslim, and a Black person, I don’t feel like I belong, and I don’t think I’ll ever belong in a community where they don’t value me as a member, and they don’t show the same respect that I show them.”

The campus bureaucracy rushed into action. David Everett, the associate vice president for inclusive excellence, explained to the campus, “Certain actions taken in that class were undeniably inconsiderate, disrespectful and Islamophobic.” Not satisfied with that, university president Fayneese S. Miller and Everett sent a joint email to students declaring, “We believe in academic freedom, but it should not and cannot be used to excuse away behavior that harms others.” Ultimately “respect, decency, and appreciation of religious and other differences should supersede” academic freedom. The offended students were reassured that the art history instructor, who has not been named, had been terminated. Over the weekend, the president followed up with another email emphasizing that the highest priority on Hamline’s campus is that “our Muslim students, as well as all other students, feel safe, supported, and respected both in and out of our classrooms.”

There is no evidence or even accusation that the instructor behaved in a manner that was intemperate, unprofessional, or incompetent. There is no suggestion that the instructional material used in the class was not relevant to the subject matter or is not important to the global history of art. The instructor emphasized to students that “I am showing you this image for a reason. … I would like to remind you there is no one, monothetic Islamic culture.” Everett, the “inclusive excellence” vice president, responded by accusing the instructor of “Islamophobia.” As another member of the Muslim Student Association noted, “Hamline teaches us it doesn’t matter the intent, the impact is what matters.” No doubt the student is accurately reporting the message Hamline has been sending to its students.

Advocacy organizations like PEN America, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, and the Academic Freedom Alliance have all taken Hamline to task for its assault on academic freedom. Scholars of Islamic history and art have emphasized that the university’s actions are an appalling endorsement of extremist rhetoric that narrows Islamic thought and restricts free inquiry. So far Miller does not seem to appreciate the damage that she has done.

There are three core principles of academic freedom and free speech that most American universities have embraced. Professors should, without fear of reprisal from their university employer, be able to research and publish controversial scholarship, be able to discuss germane but controversial ideas and materials in the classroom, and be able to speak freely and write in public “as a citizen.” Hamline University has adopted those standard policies without reservation in its own faculty handbook.

The entire purpose of such commitments is to allow scholars and teachers to engage in free inquiry without being told that they are “no longer part of the Hamline community.” There are many stakeholders—ranging from students to donors to politicians—who might be offended, threatened, or angered by scholarly work that occurs on a university campus. If students complain that they are offended by something a professor teaches them in class and the university president responds that “respect, decency, and appreciation of religious and other differences” are more important than respecting scholarly expertise on what and how university students should be taught, then there is simply no credible commitment at that “university” to scholarly inquiry and college-level education.

The implications of the principle that the Hamline University president has laid down would turn back the clock on liberal arts education in America by more than a century. If respecting students means not offending their sensibilities, and if that requirement for respect takes priority over free inquiry in the classroom, then few classrooms in the social sciences and humanities will be safe.

Surely students could similarly get a professor fired at Hamline for showing them an image of Andres Serrano’s Immersion (Piss Christ) or Robert Mapplethorpe’s Self Portrait with Whip. I assume students could likewise get a professor fired for assigning them to read Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, or perhaps even for inviting him to speak to a class. Miller, the Hamline president, would undoubtedly support the conservative Christian students at the University of North Carolina who objected to the assignment of a book that included selections from the Quran or those at the University of South Carolina who objected to the assignment of Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir Fun Home. Infamous academic freedom controversies from days of yore like the philosopher Bertrand Russell being barred from teaching at City College of New York for his outspoken tolerance for homosexuality and atheism or the biologist Leo Koch being fired from the University of Illinois for writing a letter to the student paper endorsing premarital sex regardless of “a Christian code of ethics which was already decrepit in the days of Queen Victoria” would start to seem au courant.

But one suspects that the old Animal Farm adage applies here as well: All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others. Perhaps the associate vice president for inclusive excellence will not be equally concerned with all student complaints that their deeply held beliefs and values have been disrespected by something that they encountered in a classroom. But the game of suppressing speech on university campuses that someone finds “inconsiderate” can be played by those on the right as well as the left and those embracing all manner and hue of personal identity. Such efforts have damaging effects on higher education no matter whose ox is being gored. If universities are unwilling to defend or keep faith with the most basic principles of academic freedom, they should not be surprised if alumni and politicians show little respect for them either.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.