With land wars in Europe and the Middle East and tensions running high in Asia, speculation has only grown louder that we are on the brink of or in the early stages of World War III. We are not. There has not been a foreign attack on the U.S. homeland that would motivate the country to undertake a major national effort to preserve our freedom. Governments allied with the United States are not being toppled or their territories occupied. Major powers are not fighting each other directly. U.S. troops are in combat in relatively small numbers for limited regional purposes.

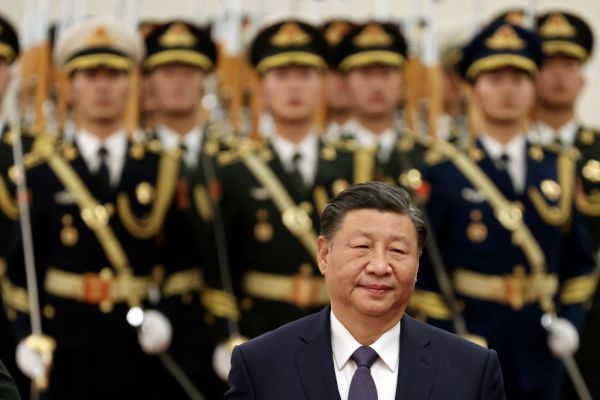

But a world war is approaching. The international order is bifurcating into ideological spheres again, with one sphere consisting of the U.S. and countries attempting to preserve gains of freedom and prosperity from the last 35 years, and another sphere consisting of countries that consider those gains to have come at their expense or endanger their domestic control. This axis of aggrieved countries includes China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. They are building the military forces to defeat us, deepening their cooperation with each other, committing acts of sabotage against us, using the openness of our societies to suborn our publics, testing our willingness to defend ourselves and our allies.

American strategy since the end of the Cold War in 1991 has been to expand the geography of free societies, particularly in Europe. It sought to advance that cause cautiously by blurring the lines between where we have undertaken solemn commitments and where we have not. So, for example, rather than hurriedly admitting former Warsaw Pact and Soviet states into NATO as they desperately wanted, the U.S. invented a “Partnership for Peace” as an intermediate step providing some connection to the club of countries for which the U.S. assumed the responsibility that “an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all.” The objective was to move incrementally so that Russia had time to acclimatize to the new reality of its diminished power. It also served to condition the U.S. public, so that by the time the question was posed of whether Poland should be allowed under the U.S. security umbrella, the answer was, “Aren’t they already?”

“The Ukraine war is a providential warning of how strong and threatening our adversaries are becoming. If we are to prevent the corrosion of the international order, we will need to restore the credibility of our commitments.”

What China and Russia have already succeeded in doing is brutally clarifying the line between what countries the U.S. will defend and those we will not. By imperiling weaker states, they have challenged the U.S. to prove we will protect them. And the last several U.S. presidents have balked. President George W. Bush committed to withdrawing U.S. troops from Iraq, leaving a government in transition subject to Iranian meddling. President Barack Obama infamously extended, then failed to make good on, threats to Syria’s Bashar al-Assad. President Donald Trump threatened to abandon NATO, declined to retaliate for Iranian attacks on Saudi Arabia, and now encourages Russian attacks. President Joe Biden has tempted China to test his blithe commitment that the U.S. would send troops to defend Taiwan—something he has done four times and been hurriedly corrected four times by administration officials. The humiliating scenes of hurried U.S. abandonment of Afghanistan and insistence of its inevitability by both the president and his national security adviser surely cause allies to question Biden’s commitments and tempt adversaries to test them.

Most conspicuously, the president has telegraphed his fear of wider war since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As Russia invaded, Biden rushed U.S. National Guard trainers out of Ukraine. He insisted there would be no direct involvement, such as providing aircraft to Ukraine or imposing a no-fly zone, saying that the U.S. helping uphold the sovereignty of Ukraine’s internationally recognized territory would start World War III. While promising to do “whatever it takes for as long as it takes,” the Biden administration hesitated to provide weapons when needed to Ukraine, often being shamed into relenting on refusals only after European allies—the countries more at risk than the U.S. from a Russian attack—had already done so.

President Biden has excluded Ukraine from our defense perimeter, just as Truman-era Secretary of State Dean Acheson excluded South Korea in 1950, drawing the line at committing the U.S. to “defend every inch of NATO territory.” Such actions encourage the axis of aggrieved to continue chipping away at the security of other states—states we are allied to or care about or rely on for our prosperity.

Our enemies have regional ambitions for conquest and are working to keep the U.S. out, because without the strength of the United States, our regional allies could not protect themselves. Russia threatens nuclear use if the U.S. aids Ukraine, hoping to forestall assistance. China attacks Philippine coast guard ships, hoping the U.S. won’t come to their aid although they are treaty allies of the U.S. North Korea fires missiles over the Sea of Japan and conducts espionage operations against South Korea, testing whether it can be peeled from the U.S. defense umbrella. Iran attacks Saudi Arabia hoping—rightly, it turned out—that the U.S. would balk at retaliation. Their ideal would be a world war without American participation, because it would result in China dominant in Asia, Russia dominant in Europe, North Korea dominant on the Korean Peninsula, and Iran dominant in the Middle East.

Those who fear the U.S. having to fight to honor our allied commitments are seeking clever legalistic loopholes to avoid war, such as pointing out that the NATO treaty technically commits the U.S. only to consultations should an ally be attacked. Such finessing ignores the strategic consequences of what would unquestionably be understood as the U.S. abandoning a commitment we had upheld for 75 years.

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte is right that free societies need to “shift to a wartime mindset.” He urges that allies are “not ready for what is coming our way in four to five years.” But we may not have four or five years—neither that time, nor success, is guaranteed to us. Even before funneling arms to Ukraine, NATO allies including the U.S. lack the weapons and ammunition to fight wars of high intensity: Ukraine uses as many artillery shells in a month as the U.S. can produce in a year. China has 371 ships in its navy while the U.S. Navy has shrunk to only 290 ships—and China’s shipbuilding can produce 230 times the output we can. Russia now commits a third of its government budget to defense and has retooled its economy to military production. North Korea is providing Russia the troops it needs for the war in Ukraine, Iran is providing its drones, and China is providing the war materiel.

The best, and cheapest, way to win wars is to prevent enemies from believing they could win. Accomplishing that (what in defense circles is termed reestablishing deterrence) will require committing to a dramatic increase in defense spending, invoking the Defense Production Act to accelerate weapons and ammunition production, and recruiting a larger conventional force. Those measures would strengthen the U.S. military and likely prevent an attack on our country. Hard choices and hard work will be needed to rebuild our military strength: Money will need to be diverted from other worthy and pressing needs, young Americans will need to be persuaded into service, comfortable practices will need to be disrupted, we will need to let our military focus on its core mission and leave it out of culture wars, and leaders will need to act as statesmen. Those elements were little in evidence in the Biden administration, and a Trump administration will add new challenges.

But those measures alone wouldn’t be sufficient to prevent attacks on allies, because our enemies will still be tempted to test our willingness to protect countries we have committed to protect. The Ukraine war is a providential warning of how strong and threatening our adversaries are becoming. If we are to prevent the corrosion of the international order, we will need to restore the credibility of our commitments. And that means giving less weight to our fears and engendering greater concern on the part of China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. Otherwise, the U.S. will be left standing like a walled medieval city, itself safe but impoverished and surrounded by hostile forces.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.