By many measures, it should be a good year to run for reelection as an incumbent Republican U.S. senator.

Twenty-one GOP-held Senate seats are up for reelection this midterm cycle and 14 Democratic-held seats are up—all in states that President Joe Biden won in 2020. Wisconsin is one of only two states—along with Pennsylvania—that Biden won and where Republican senators are mounting reelection campaigns this year. Biden won the Badger State by a slim 20,000 votes out of more than 3 million cast.

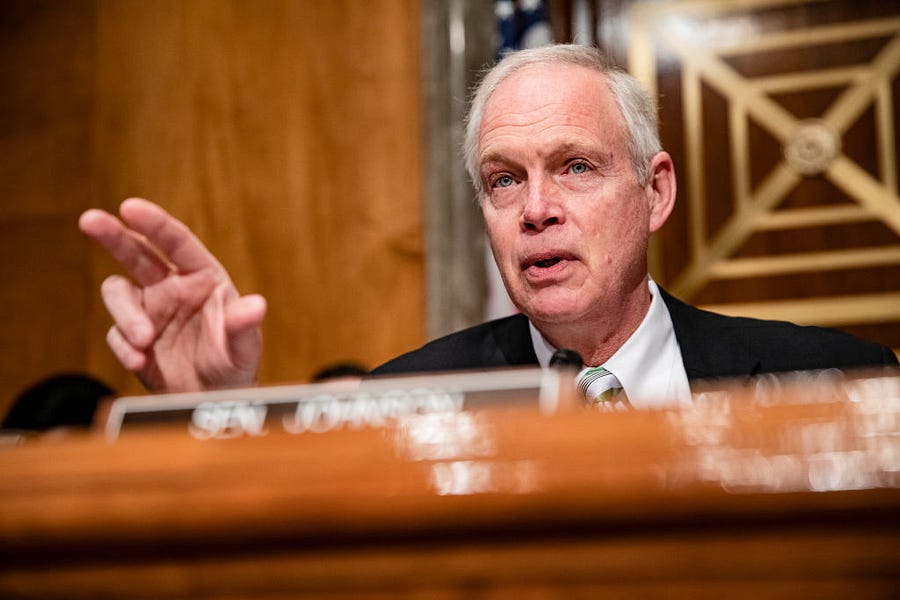

But Democrats are eager to parlay Wisconsin’s 2020 support for Biden—even if marginal—into a critical loss for incumbent Republican Sen. Ron Johnson and boost chances of hanging onto control of the Senate in November. Johnson is arguably the most vulnerable GOP incumbent on the ballot this cycle. Even with Biden’s low approval in the state, Johnson has not seemed to benefit by comparison: His favorability in state polling is underwater and has not shown much improvement.

The Democratic Party is poised to drop millions to try and unseat Johnson in November. But his supporters warn against underestimating the sophomore senator, who has previously demonstrated an ability to emerge from sagging poll numbers. He has survived grim odds in cycles that looked a lot worse for Republicans, particularly in 2016.

“I would never, ever in Wisconsin bet against Johnson,” former Rep. Reid Ribble, a Wisconsin Republican, told The Dispatch. “There’s nobody on the campaign trail that works harder than he does. If he can pick up some of the suburban voters that voted against Trump in 2020 he’ll be fine.”

Wisconsin’s primary comes late in the cycle, on August 9 (Johnson faces no Republican competition). In addition to the Senate contest, voters will also weigh in on contests for governor, the state assembly, attorney general, and secretary of state, and political watchers said they expect that engagement will be high due to the high-profile Senate and governor’s races.

“We are one of the most perennially competitive states in the country for elections,” Jason Stein, research director of the Wisconsin Policy Forum, told The Dispatch. Voters in the state know, he said, that “sometimes in Wisconsin even statewide elections are decided by very slim margins.”

Johnson entered the political scene as a Tea Party disrupter with a fiscally conservative message and has developed into a fervent Donald Trump devotee.

He mounted his first race in 2010 as a political outsider: He was a wealthy businessman and CEO of a polyester and plastics manufacturer, with a relatively unknown profile.

That year, he swept the Republican primary and went on to defeat incumbent Democrat Russ Feingold by capturing 52 percent of the vote, running on a Tea Party message. He tapped into voters’ frustration with the Obama administration’s approach to health care, big spending, and the Democratic establishment’s control of Washington.

Fast-forward to the 2016 cycle: Johnson began his reelection campaign as “the most vulnerable senator on the map,” according to the Washington Post. Poor favorability ratings dogged him through much of the race, but by November, he’d tightened his favorability number to a dead heat with Feingold and won the election by a razor’s edge—50.2 percent of the vote.

Six years later, Democrats once again view Johnson as the most vulnerable incumbent.

They have the data on their side. Marquette Law School’s polling—described by University of Wisconsin-Madison politics and law professor Kenneth Mayer as the state’s “gold standard” of polling—shows that a high share of voters view Johnson in a negative light.

An analysis of polling in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel noted that during Johnson’s last reelection campaign, his net favorability ratings rose from minus-11 in fall 2015 to plus-1 by March 2016. By contrast, this cycle, Johnson’s ratings were at minus-7 last summer. The number sank to minus-12 this February, and as of the latest poll in April, stands at minus-10. The state party crowed at the modest improvement, but it’s too soon to tell whether it represents a turnaround for Johnson.

“He’s been on a steady decline of net favorability since the end of 2019,” pollster Charles Franklin, director of the Marquette Law School Poll, told The Dispatch. “This trajectory runs through all of 2020, all of ‘21, so far all of ‘22. We’re not talking about a blip or an outlier.”

Compared to 2016, Johnson also has less of a window to impress voters unfamiliar with him. In 2016, Franklin noted, around 35 percent of voters counted themselves as unfamiliar with Johnson: “But the ‘don’t know’s’ went down, and the favorables went up with almost no change in unfavorables. He converted ‘don’t know’s’ into favorables in that recovery period.”

But currently, the “haven’t heard enough” combined with the “don’t knows” on the question of Johnson’s favorability count for 18 percent of responders—half of 2016’s number.

“There’s a much smaller pool of people he could convert into favorables,” Franklin concluded. “The trend from 2019 has been almost entirely a growth in unfavorables.”

Likely fueling the net negative image of Johnson is a series of controversies sure to come up throughout the rest of the campaign.

“He’s in trouble, there’s no other way to slice it,” Joe Zepecki, a Milwaukee-based Democratic strategist, told The Dispatch. “The amount of controversy that he has generated, the degree to which he has become so polarizing, is entirely a function of his inability to just keep his mouth shut.”

Johnson said on January 2, 2021, he would vote to reject Biden electors from some states and made media appearances arguing that allegations of voter fraud in the presidential contest needed investigation. Two days later, he virtually joined a meeting with conspiracy theory peddler and MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell, a Trump ally, who was encouraging senators to delay the certification of election results.

Following the Capitol riot on January 6, he changed his mind and voted against the challenges to certifying the votes. But he also downplayed what happened, calling the day’s events “not an armed insurrection and it was, by-and-large, peaceful” and suggesting at a Senate hearing that the violence of the day came from “fake Trump protesters.”

He also has left the door open for COVID-19 conspiracy theories, drawing criticism for touting misinformation related to the virus and pushing unproven medical treatments. At one Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee hearing, Johnson’s invited expert witnesses included doctors who were skeptical about the coronavirus vaccine and who promoted the use of unproven drugs such as hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin. Another instance that drew particular heat was when Johnson didn’t refute attorney Todd Callender’s false claim that COVID-19 vaccines give people AIDs during an interview. His office later said in a statement that Johnson does not “believe that the vaccine causes HIV.”

Johnson has become a lightning rod in particular among the “WOW counties,” the suburban Milwaukee outposts of Waukesha, Ozaukee, and Washington that may be key to the outcome in November. For years the WOW counties’ population of college-educated, suburban voters have been mainstays of Republican support. But they soured on Trump in 2020, and polls since show Johnson’s favorability eroding there as well.

Johnson’s slippage in the suburbs could be due to the number of times he’s landed in hot water, largely for lending credence to conspiracy theories on COVID-19 and the 2020 presidential election. These remarks have led to a flat-out war with the Milwaukee media market, which has unsparingly covered his various gaffes and controversies. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel’s editorial board called for Johnson to resign earlier this year, saying he, along with other elected Wisconsin Republicans, “incited” January 6.

“His statements on COVID-19 have been—they’ve just been wacky. His embrace of quack medicine and then, as far as his other statements go on like on January 6 for example, I do think that just contributes to the impression he’s out of touch,” James Widgerson, former editor of RightWisconsin, told The Dispatch. “I wouldn’t say he’s been focused on the kitchen table issues—the issues that have made Joe Biden unpopular. … Instead he’s just become the senator of conspiracy theories.”

Mayer, the University of Wisconsin-Madison professor, told The Dispatch that Johnson’s controversies are “the sorts of things that, in a state like California or Alabama, they would probably not make a difference. In a state that is likely to run 50-50 plus or minus, those things can matter. The fact is, Johnson is more controversial than he was in 2016.”

Johnson also has tied himself closely to Trump, who is not very popular in the state overall. Marquette found that 36 percent of registered voters there viewed the former president favorably, while 58 percent viewed him unfavorably.

But polarization cuts both ways—and the same statements that have inspired loathing among Johnson’s detractors have had the opposite effect on the Republican Party base.

“The things that have gotten him in trouble with independents have maybe helped him with core Republican constituents,” Franklin said.

When he took the stage at the 2022 state GOP convention in Middleton in mid-March, there was little doubt that he had the support of the party faithful. The crowd gave him a standing ovation as he rose to speak, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

While lauding Republicans and chastising Democrats, he also took the time to strike at his political enemies. Negative press coverage topped the list.

“I have an opponent,” he said. “Probably the worst opponent anyone could have. I have the media against me.” The press, he said, would treat him differently if he were a Democrat.

But Johnson is aware that he can’t win in November with the base alone, so he has tried to appeal to the middle.

In January, when announcing he would run for reelection via a Wall Street Journal op-ed, he focused on GOP priorities in investing in the military, creating a healthy economy, and cutting back regulatory overreach. Other talking points focused on red meat for the Republican base: the Biden administration’s “failed response” on COVID-19, crime, and the cost of living. The overall measured tone steered clear of the messages that had sparked controversy elsewhere.

While it remains to be seen which tone will carry the day as the campaign heats up, Johnson is not someone to back down from a tough political fight.

Ribble said part of Johnson’s appeal is the way he connects with voters. “He’s just, absolutely everywhere. When he is back in the state he is at work. As divisive as he might be in the general public, and it’s maybe because he’s become enemy number one of the media in Wisconsin—he’s well liked by the Republican base.”

Democrats, meanwhile, have yet to coalesce around one candidate in the Democratic primary for Senate, which features 10 candidates in all. Only four show significant polling numbers, and the state party is remaining steadfastly neutral in the race.

Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes started as an early favorite in the polling due to name recognition and ran 10 points ahead of the primary field earlier in the year. Barnes has earned high-profile endorsements, including Democratic Sens. Cory Booker of New Jersey and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn of South Carolina, and the Working Families Party.

But the NBA’s Milwaukee Bucks executive Alex Lasry, who is partially self-funding his bid, has dropped more than $5 million on advertising in the race since last October and is closing in on Barnes. April’s Marquette poll showed the two within the margin of error. Lasry is a political newcomer, whose website touts endorsements from a slew of local labor unions and focuses on the job creation brought about thanks to his family’s building of Fiserv Forum, the Bucks’ arena.

Lasry’s surge seemed to catch Barnes somewhat flat-footed: He did not respond with television advertising of his own until mid-May.

Another primary challenger is state treasurer Sarah Godlewski, who has also spent millions of her own dollars in the race. She trails in third but has gotten a bump in the polls since February, when she pivoted to focus on abortion following the leak of the Roe v. Wade draft opinion. She’s earned the endorsement of the pro-abortion rights group EMILY’s List.

“I don’t think the contours of the race have fundamentally changed—I still think Barnes has the advantage. But Lasry is certainly within shouting distance,” Zepecki said.

Outagamie County Executive Tom Nelson is also in the race, so far squarely occupying fourth place despite having announced his run in October 2020. According to Zepecki, Nelson has occupied “what I would call the Bernie Sanders lane and has been very aggressive.”

But there’s still room for major shifts in the Democratic primary: Nearly half of registered voters told Marquette they’re undecided.

“The thing people need to really understand is Wisconsin was cleaved and totally polarized and all of this shit before it was cool. We’ve been doing this for 10 years now,” Zepecki said. “This is as divided a state as there is in the country politically. … Fifty-five percent in this state is equivalent to Brian Kemp getting 72 percent in the primary in Georgia—that’s how big of a blowout that represents.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.