Let’s skip ahead to after the election. No matter who wins, the next president will declare that they have a “mandate” to do something. And they will be wrong.

The whole canard that a newly elected president is for some reason entitled to have their way is an invention. The word “mandate” doesn’t appear in the Constitution or the Federalist Papers.

The myth can be traced to Andrew Jackson. He shuttered the Second Bank of the United States partly on the grounds that he ran on doing so—though his campaign hardly revolved around the issue—but he relied even more on the notion that he was “the people’s president.” Jackson introduced the argument that because the president is elected by the whole country, his agenda has unique legitimacy and urgency. This “constituted a revolutionary change in the conceptualization of the basis of presidential power,” the presidential historians Richard J. Ellis and Steven Kirk wrote, establishing the idea that the president derives some extra-constitutional authority from his connection to the people.

Abraham Lincoln and Woodrow Wilson—presidents I respectively revere and despise—furthered this conception of the president as an avatar of the national will. Most famously in his Gettysburg Address, Lincoln elevated the logic and language of the Declaration of Independence to justify a Union victory and the emancipation of the slaves and to enshrine equality before the law as central to America’s purpose. Wilson just wanted to wield as much unchecked power as possible.

Proponents of the idea that the president is the singular instrument of the “will of the people”—sometimes called the “plebiscitary mandate”—typically insinuate that presidents outrank Congress because they have the backing of a national majority while legislators wield only narrow, sectarian mandates from their districts or states.

This is anti-Constitutional, quasi-authoritarian, mystical codswallop.

The Constitution is incandescently clear on this point: Congress is the supreme branch of government. It writes the laws, declares war, levies taxes, creates most of the courts and executive agencies, and pays their officials’ salaries. It can fire members of the other branches, but the other branches can’t fire members of Congress.

Congressional majorities—and hence congressional mandates—form around specific issues and interests as a result of deliberation and compromise. Or at least they do when Congress works.

The political scientist Julia R. Azari has identified two other theories of presidential supremacy: the “critical election” mandate and the “responsible party” mandate. The former holds that some elections represent an inflection point or realignment that signals popular approval for a new direction, which Franklin D. Roosevelt claimed in 1933. The latter says that if a candidate runs on explicit promises or policies, the voters have a right to expect the government to deliver them.

These are real conceptual distinctions, but in terms of practical politics and constitutional legitimacy, they’re just different flavors of the same nonsense.

Which brings me back to this election. Vice President Kamala Harris has been shrewdly opaque about her agenda; she has been far more detailed about the positions she no longer holds than she has about the ones she does. When asked for specifics about what she would do if elected, she often offers word salads and nostrums about bringing people together. Beyond fighting for expanded abortion rights, her only plausible claim to a mandate is not being Donald Trump, a pledge she would achieve on “Day One.”

Trump hasn’t offered many specifics either, but some of the few he has are very controversial. Many of his supporters insist he doesn’t really mean them: Take him seriously, not literally, as they say. He won’t really send troops and police officers to drag millions of immigrants who are here illegally from their homes, presumably to put them in camps before deporting them. He won’t actually impose massive, across-the-board tariffs or prosecute his political enemies in pursuit of “retribution.”

But you can be sure that if he is elected, many Republicans will claim he has a mandate to do exactly that. Perhaps that would help progressives who love the idea of presidential mandates—when they win—see the problem with them.

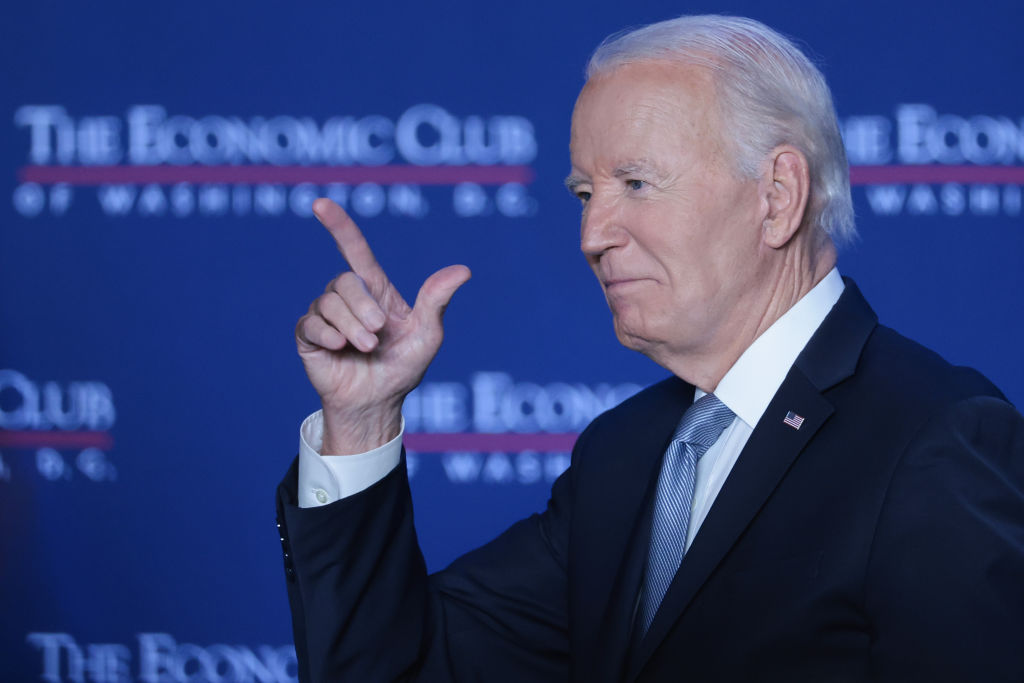

But the core problem with mandate-mania is this: Presidential electoral majorities never speak with one voice in favor of a policy platform. In 2020, many people voted against Trump more than for Biden. Virtually no one voted for him to be the reincarnated FDR, as a cabal of historians encouraged him to be, after he was elected. If voters wanted that, Biden would have campaigned on that and voters would have elected the congressional majorities they gave Roosevelt.

Presidential elections are job interviews. The person the voters hire will have only one real mandate: to do the job delineated by the Constitution.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.