What is manhood? What does it require?

Most men and most civilizations have grappled with these questions. In The Iliad, Homer presented Achilles and Hector as two divergent, embodied exemplars, asking his audience whether the mortal defender or the demi-god conqueror is more worthy of the term. Centuries later, Saint Paul encouraged the early church in Corinth to “Keep alert, stand firm in your faith, be courageous, be strong.” In many translations, “be courageous” is rendered as “act like men.”

Reckoning with the meaning of manhood is not new, and yet today it is often treated as toxic or problematic. It’s troubling, and not simply because the trend might lead our culture to answer the question—what does it mean to be a man?—incorrectly. Rather, our aversion to masculinity might keep us from asking this question in the first place, letting its meaning become a relic of a quaint past. Yet it’s an essential one to reevaluate.

Over the last half-century, American men have undergone a transformation. In 1990, 1 in 33 reported not having a single close friend. That figure is nearly 1 in 6 today. Somewhere around 10 million working-age, able-bodied men have opted out of the workforce (many rely on the beneficence of their family or social safety programs to get by, and they report much higher screen time than their working counterparts). Rates of single motherhood have doubled since 1968, with fathers leaving their children’s lives or never entering them at higher and higher rates. And 1 in 4 American children live without a father in the home, biological or otherwise. As Sen. Chris Murphy recently remarked, many men today are in the middle of an identity crisis.

These shifts—growing anomie, declining workforce participation, reduced attachment to institutions like family—have borne bitter fruits. Men have fallen far behind women in postsecondary achievement and even K-12 academic performance. They suffer from drug addiction, deaths by suicide, and depression at alarming rates. And men and women are increasingly “going it alone,” uninterested, unwilling, or unable to find a long-term partner, let alone a spouse.

Masculinity in 21st-century America, then, often means being lethargic, alienated, and afraid to form intimate bonds. That’s been the trend for the last 50 years at least, with little sign of change.

Lost in these statistics and many subsequent analyses, however, is the integral connection between men’s contemporary woes and our escalating social atomization. From Alexis de Tocqueville to Robert Putnam, observers of America have discerned a rising tide of hyperindividualism that threatens not only personal happiness but broad-based civic flourishing. Put simply, people are doing fewer things together.

Participation in civic organizations is declining. For the first time in American history, church membership has dipped below the majority of the population. Men are more unchurched than women, with 46 percent of men compared to 53 percent of women belonging to a house of worship. Equal parts of men and women report feeling lonely—less than half of Americans say they are “not at all lonely.”

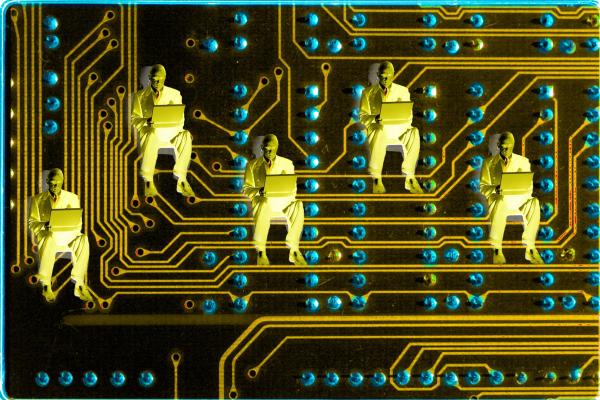

Technology deepens this inward turn, enabling people to order food, forge friendships, chat with potential romantic partners, and even “participate” in worship services without ever leaving the house or interacting with other people face to face. We have secured for ourselves, in the words of the late David Foster Wallace, “The freedom to be lords of our own tiny skull-sized kingdoms, alone at the center of all creation.” But this freedom comes without a compass and a defined role for companionship, leaving men (and women, for that matter) adrift. We have never been more capable of navigating the oceans of our lives, and we have never been less capable of deciding where to set sail. In turn, many have opted to stop sailing, so to speak.

Defenders of traditional forms of social organization are used to describing institutions like marriage and religion in terms of how they sculpt our desires, polishing rough edges and redirecting our energies toward the good. But in our time, as political theorist Yuval Levin has pointed out, institutional breakdown has left many young people vulnerable to a sort of “disordered passivity.”

The problem is that these fading institutions often summon manhood. They ask and respond to the question, “What does it mean to be a man?” And they do so not through public argument but through the obligations they establish, the roles they forge. Manhood is more than a concept floating in the void of intellectual discourse; it’s grounded in real institutions and embodied by real people. Put another way, manhood is defined not primarily by colloquy nor personal whim, but by the people, places, and institutions that demand something from us as men.

Strong marriages demand that men, as husbands, care for and love their spouses. Strong families demand that men, as fathers, dedicate substantial time to raising their children and putting loved ones before themselves. Strong religious communities demand that men, as congregants, love the other. These mutual obligations swim against the current of hyperindividualism, shaping us into better people and better men, calling us out of ourselves and teaching us that there’s more to life than endless self-seeking.

They also strengthen women and children who love and rely on us—and those who long ago wrote off relying on the men in their lives. Daughters deserve fathers who give them an example of how men ought to treat them. Sons deserve fathers they can look up to as role models. Wives deserve husbands who embody sustained commitment and care despite the tempests that accompany every good marriage.

It’s tempting to approach the problems men today face one-by-one. We could address psychological distress by investing more in counseling, or declining workforce participation by establishing new community outreach programs. Such solutions have their place. But lasting solutions must get to the root of the problem: atrophying social bonds and the precipitous decay of the institutions that give them substance and form. Without addressing the excesses of hyperindividualism, men’s problems will continue apace, even if patchwork fixes slow the bleeding.

So any approach to the malaise confronting men will first demand that we reorient ourselves toward obligation and formation. Before enumerating to-do items or formulating action plans, we must commit ourselves—again and again—to living for more than base self-satisfaction. Manhood is not worthy of its name if its lodestar is “self-discovery” or the pursuit of pleasure. To be a man is to nurture, strengthen, and fulfill one’s obligations to others, especially those whom we are bound to through institutions like marriage, family, and faith. Manhood is a rite of passage, not a right of birth.

While the instruction of male role models is a good start, this education must ultimately be embodied in traditions and institutions that actually demand something of men. These social structures encompass religious communities, fraternal organizations, sports clubs, and a plethora of other institutions. Joining such organizations, and dedicating even just a few hours a week to their efforts, is integral to solving the unique problems facing men and boys in the 21st century.

Of course, it is difficult to join and participate in embodied community—not to mention marriage and family—when such communities continue to disappear. Rotary Clubs and American Legion posts are frantically searching for new members to stay afloat. Veterans organizations like the Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars are struggling to balance their books. Religious institutions like the Roman Catholic Diocese of Baltimore are shrinking from 61 to 30 parishes in the coming years. Fewer parish fish fries and fewer Friday night beers at the local Legion post are genuine cause for concern.

That is why many of us men must not only join; we must also build. Practically, it has never been easier to form new communities and institutions of civil society. We have technology to thank for reducing barriers to entry: Websites can be built in a matter of hours, publications can be created without purchasing a single printing press, and even social media—when used appropriately—can make it far easier for people to come together in-person.

But to be sure, a flourishing, less atomized masculinity will need to rethink its relationship with technology. As of late last year, American teens spent 4.8 hours per day on social media. Nearly half of teens report using the internet “almost constantly.” Technology broadly, and social media in particular, is a simulacrum for embodied interaction, and a poor simulacrum at best. Social media demands nothing of men other than their data and attention; it exacts no promises, calls us to no higher purposes. Such a “life” breeds eternal adolescence. It is poor soil for the rites of passage that manhood requires.

Putting technology in its place will require friends to lean on and mutual support groups to enforce. App-blocking settings and services can be incredibly useful, particularly if you’re willing to exchange passwords with friends who vow not to divulge it unless there is a genuine emergency. Accountability is key. Even reducing screen time by one hour per day can prove remarkably advantageous. Public policy may also be helpful here. As the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has pointed out, reducing social media usage on a larger scale without some sort of policy intervention is incredibly difficult because of the power of network effects, whereby social media services increase in value as more people use them, making detachment harder.

Cultural change is no small task. It will ultimately cement itself not in the habits of the few who happen to engage with these issues today, but in the social institutions they found and join, in the forms and mores that cement themselves into place over time. Good things take time. Patience and diligence are prerequisites.

But detached from obligation—and from the institutions that conjure, enforce, and honor our allegiance to such obligation—men are lost at sea. No self-help book, no YouTube celebrity, no “sigma male mindset” will set us back on course. Manhood can only be salvaged through a recommitment to the institutions of civil society and the obligations they summon. Manhood can only be saved by taking the marvelous risk of living for more than oneself.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.