Israel’s strikes on the heart of Iran’s regime are already shaping up as one of the most ambitious and effective campaigns by a military long known for operational daring and excellence. By trying to forestall an existential threat to itself, Israel in effect is also upholding decades of official U.S. policy to do whatever it takes to keep Iran short of a bomb.

But will Israeli action and determination be enough? Equally important, if the United States does get involved, what all would be needed, on top of everything Israel already is doing, to best ensure America’s enduring redline can be fulfilled after years of costly inaction?

Israel’s operational successes have been nothing short of remarkable. In just days, really within the space of 24 hours, it all but erased primary nodes of Iran’s military command and control and its nuclear infrastructure. This includes seriously damaging key nuclear facilities and wiping much of its atomic hard drive by killing weaponization scientists and their managers. Israel securing air dominance over three adversaries in 1967, or the Wehrmacht annihilating Stalin’s air force in 1941, seem the only modern analogues to these battlefield victories in the crucial opening phase.

Yet operational success, no matter how stunning, does not bring strategic closure. The countless Soviet and Arab planes destroyed on tarmacs and runways did not stop those countries from reconstituting their forces, devising new strategies, and living to fight another day fairly quickly.

Similarly, Israel’s sudden achievements now raise as many uncertainties as they resolve. Despite initial gains exceeding what many had thought possible, the war could still go on for weeks or even longer, and Israel is expanding beyond atomic infrastructure and missile arsenals to target Iran’s intelligence services, defense industry, energy installations, and other core regime pillars. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has encouraged Iranians to rise up, underscoring that Israel seeks not merely to roll back Iran’s nuclear program but to end it by precipitating the regime’s collapse.

This poses a weighty and urgent strategic dilemma for the United States. Five presidents in a row, including President Donald Trump, have sought a political solution to Iran’s nuclear threat. The net result was Iran’s march to the threshold of the ultimate weapon and, in turn, Israel’s imperative to pursue its own political endgame, premised squarely on using military force.

Amid a pummeling for which it was disastrously unprepared, and wanting to terminate current hostilities as rapidly as possible, Iran’s regime will try to exploit any daylight peeking through these U.S. and Israeli approaches, without actually negotiating away whatever nuclear program it has left. Iran indicates potential willingness to return to talks, but only after the shooting stops—and it is not offering new concessions. Both right before and after Israel’s opening blows, Iranian officials vowed to end international oversight of their country’s nuclear activities, and suggested they would relocate sensitive materials to secret sites. Tehran has vowed routinely to present the world with a nuclear fait accompli if attacked.

Short of Iran reversing course and fully dismantling its entire nuclear program, ending the war now would give it precious breathing space to rebuild. But staying above the fray and trying to leverage Tehran’s predicament diplomatically, an option the president left open on Tuesday, raises essentially the same risk. It constitutes a real gamble that Israel can achieve decisive results—either triggering regime collapse or, at the very least, meaningfully shutting off Iran’s path a bomb—before what’s left of the Iranian state scrapes together its atomic remnants and assembles a nuclear device.

Regime collapse is certainly a sensible goal at this point. But the actual process is nearly impossible to game out. Iranians are already taking to the streets in certain instances, yet it is incredibly challenging to foresee whether the security services will be able, or willing, to suppress a spiral into widespread protests and subversion. This is a key “known unknown” determining regime implosion, and it becomes even less knowable with those forces in the throes of a war that has upended their chain of command.

“Amid a pummeling for which it was disastrously unprepared, and wanting to terminate current hostilities as rapidly as possible, Iran’s regime will try to exploit any daylight peeking through these U.S. and Israeli approaches.”

Even with the rapid upheaval to Iran’s military leadership—Israel has taken out at least 10 high-ranking generals so far—its collective memory remains seared by the formative eight-year death grapple with Iraq, similar to how Nazi Germany’s overlearning of the lessons of World War I drove it to fight to the bitter end of World War II, trusting in wonder weapons and redoubled defiance to overcome ever-longer odds. Moreover, Saddam Hussein lost his life, and Bashar al-Assad his throne, after each failed to rebuild his nuclear weapons program following Israeli strikes. With decision-makers in Tehran likely viewing unfolding events through such prisms, can America afford to bet the regime won’t do everything possible to finish a nuclear bomb post-haste?

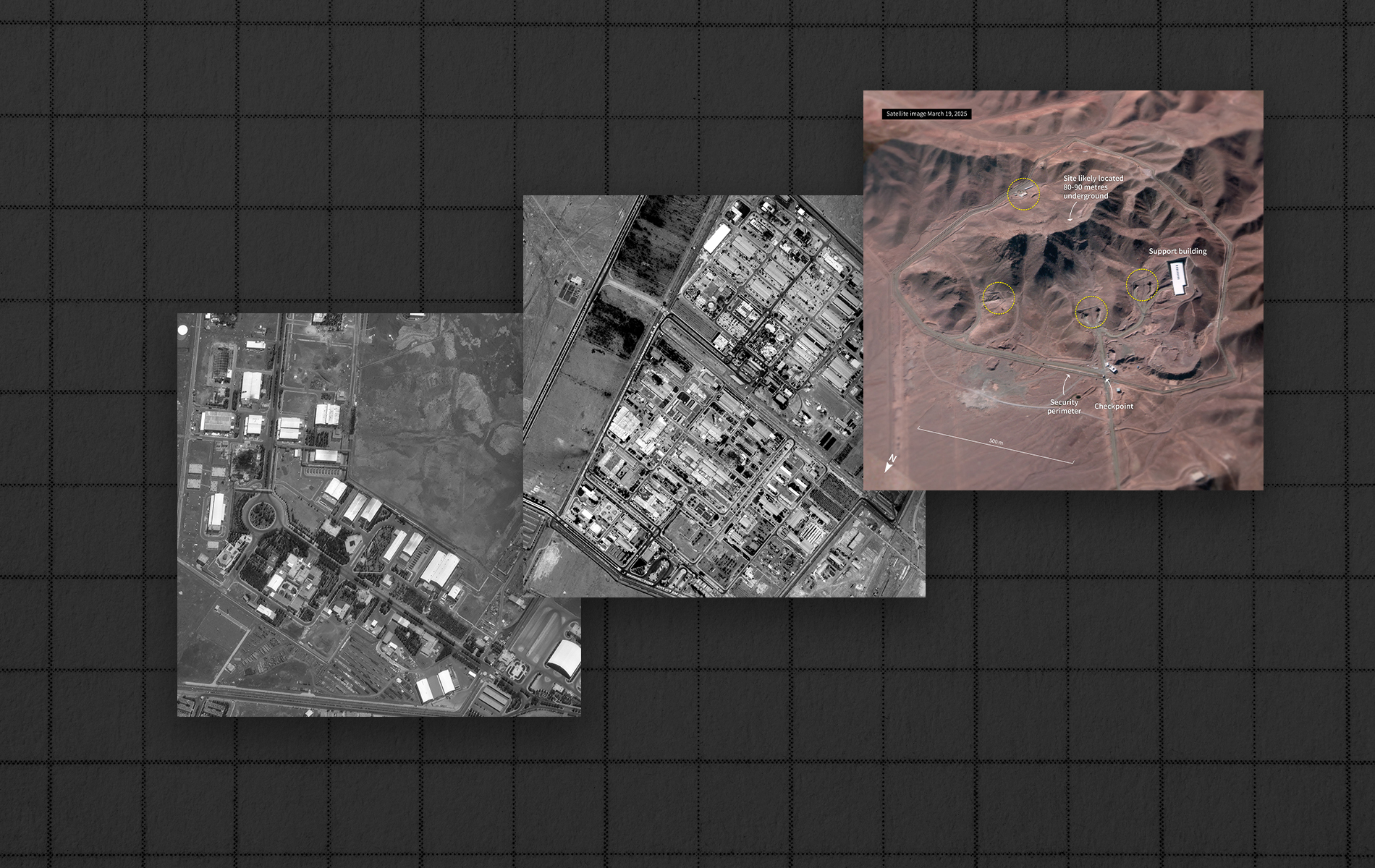

Tehran’s nuclear program is built specifically to survive Israeli military action. The regime studiously avoided Iraq’s and Syria’s mistakes of concentrating on singular aboveground sites and relying on foreign suppliers for critical materials and components. It has a deep history of building enrichment sites covertly, producing and storing centrifuges in undeclared locations, and shrouding weaponization in Manhattan Project-level secrecy. Rafael Grossi, chief of the International Atomic Energy Agency, has warned for years that he cannot rule out secret sites somewhere in the country. And despite the decapitation of Iran’s scientific expertise and program leadership, presumably knowledge survives of enriching uranium to purities suitable for a crude but testable device, and designing such a device. It would be but a small jump from there to making the fissile material and other components of a nuclear warhead.

In these contexts, an American decision to strike Iran’s facility at Fordow would be necessary, but also insufficient, to reliably prevent nuclear reconstitution and achieve the president’s goal of “a real end” to the conflict—a “complete give-up” by Tehran. Home to Iran’s most sensitive enrichment, Fordow sits under hundreds of feet of solid rock and is effectively immune to all but the most powerful U.S. bunker busters. Neutralizing it would eliminate the last known cog in Iran’s machine for finishing all the ingredients of a bomb.

But even with Fordow out of the picture, sound military planning would have to assume Iran retains enough leftover capacity, know-how, and motivation to pick back up. Those same planners also should expect that any recrudescence will be even harder to detect and stop. Ever since the first concerted attempts to disrupt Iran’s nuclear progress in 2010, when the Stuxnet cyberattack throttled Iran’s main enrichment plant and key scientists began being killed, Iran has improved its ability to absorb these blows, move farther underground, and work more secretly without missing a beat.

The optimism engendered by Israel’s successful operations, which now leave Fordow open to attack, must be leavened by such considerations. The current situation also should be seen in the context of a larger historical trend where military and strategic assets become increasingly hardened and in-depth the more they are pulverized by bombing. In World War I, defenses on the Western Front countered evermore powerful, accurate, and sustained artillery barrages by sheltering under reinforced concrete and echeloning in multiple layers, leaving no single line or point critical to overall survival. During the next war, German munitions output grew steadily in the face of massive bomber raids as it spread subterranean factories throughout the interior of its territory.

Just as it took sustained and intensive efforts to overcome these measures in wars past, therefore, preventing Iran’s nuclear reconstitution will entail a broad campaign. Taking out Fordow would sharpen Tehran’s choice between relinquishing the rest of its nuclear enterprise permanently, verifiably, and totally—including ballistic missile programs—or facing the combined might of the United States and Israel. Even if the regime opts once again to “drink the poison chalice” and admit total defeat, as Supreme Leader Khamenei’s predecessor did in ending the Iran-Iraq War, it should be with the full understanding that any future rebuilding effort would seal the regime’s prompt demise via the full force of U.S.-Israeli action.

With Iran’s air defenses now obliterated, the Trump administration also should deploy U.S. air assets in Iranian skies to assess the extent of damage being inflicted and detect possible reconstitution. Meanwhile, American aerial refueling tankers should support strike, reconnaissance, and other Israeli operations taking place over unprecedented ranges with incredibly demanding logistics. The administration should coordinate closely with Congress on key decisions, particularly in light of recent concerns from members of both houses about Iran’s approach to the nuclear brink. After having been largely shut out of nuclear negotiations for more than a decade, the legislative branch could reinforce and amplify signals of Trump’s seriousness about preventing a nuclear Iran.

An overused but salient military maxim cautions that no operation enjoys certainty beyond the first encounter with the enemy’s main forces. On one level, this can be understood positively. The first phases of Israel’s evolving operation will be studied in staff colleges a century hence, as they have exceeded even the rosiest prewar benchmarks for success. But now, as Trump considers how to leverage these gains and end Iran’s nuclear pursuit, he should do so with one idea front of mind: Tehran’s nuclear battleplan is to survive first contact with the enemy, then rebuild in the thick fog of uncertainty that inevitably compounds as conflict unfolds.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.