Last month, an assailant targeted two Minnesota state lawmakers and their spouses, killing one couple and gravely wounding the other. A few weeks before that, two staff members from the Israeli Embassy were tragically shot and killed on the streets of Washington, D.C., just days before they were set to become engaged. In April, an arsonist set fire to the Pennsylvania governor’s mansion during Passover, forcing Gov. Josh Shapiro and his family to evacuate the building. In September, bullets tore through the doors and windows of the Arizona Democratic campaign office. On the campaign trail last July, President Donald Trump miraculously avoided assassination.

These are not isolated incidents; they are alarming, all-too-frequent signals that our civic fabric is fraying. Politically motivated violence is on the rise in America. Each new horrific act underscores a deepening rupture in our culture that illustrates a breakdown in shared civic norms and mutual trust. Violence, after all, is downstream of dehumanization, and we’re in a moment of increasing detachment. More and more, we see others not as fellow citizens but as threats. Solving this crisis requires more than policy. It begins at the most personal level, with how we treat each other.

Just 11 percent of young men today strongly disagree that violence is ever justified when politics fail. This alarming statistic, drawn from a recent survey from the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute, doesn’t reflect a generation that’s gone astray; it reflects an entire civic culture in decline. In the age of viral outrage and performative politics, our discourse is increasingly shaped by spectacle rather than persuasion, and volume rather than virtue.

And yet, history reminds us: We have endured division before.

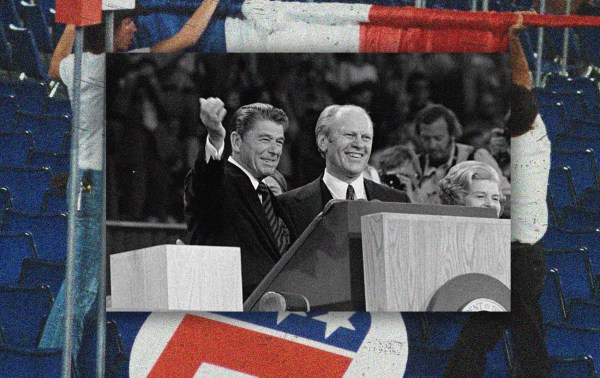

Bitter divides over the Vietnam War, economic stagnation, a long hostage crisis, and a national malaise beset the country between 1960 and 1980. It was into this thicket that President Ronald Reagan stepped. In an era every bit as complicated and contentious as ours today, he reminded Americans of the ideals we have long shared, not only through rhetoric but through his actions. He asked us not to look inward in fear, but outward in hope. By 1984, he carried 49 states. Confidence began to return. Not just in government, but in ourselves.

“Reagan taught us a crucial lesson that’s in short supply today: In a healthy democracy, everyone needs a way to leave the room with dignity.”

I had the privilege of witnessing this transformation up close. I served on his White House staff as an assistant to the president, and later as his chief of staff after he left office. What I saw in Ronald Reagan was something deeper than political skill: a moral imagination, rooted in humility, human connection, and principled compromise. He embodied a model of leadership that prized storytelling over shouting and connection over confrontation.

As Jonah Goldberg explained on The Remnant, Ronald Reagan’s genius was in how he communicated:

He just tells stories that people regardless of their partisan or ideological affiliations have access to, because they’re stories. … He was a guy who cared a lot about ideas, but he did not convey ideas by getting abstract. He conveyed ideas by telling stories about the human experience, which is the way our brains are actually designed to receive information.

In that spirit, let me share a few stories of my own: quiet but instructive moments that reveal the heart of the man and offer lessons for our fractured times.

One evening well into retirement, Reagan was at a fundraising dinner at the Eisenhower Library, surrounded by a throng of admirers. Every time he lifted his fork, someone appeared with a camera, an autograph request, or a family story. He was constantly interrupted and barely got a chance to eat. It was, frankly, exhausting. Afterward in the car, I broached the subject gently, preparing to apologize for what could have been better staff work. “Let me raise something about how our evening went …” I began. But before I could finish, he turned to me with a warm smile and said, “Aren’t people wonderful?”

To Reagan, the interruptions weren’t intrusions but reminders of the connection he had forged with citizens from every walk of life. That instinct—to assume the best in others, to see dignity in everyone, to look past inconvenience—was part of what made him so effective. He didn’t see people as distractions. He saw them as his fellow Americans. And he liked them.

Another occurred when we were running late on a busy trip. The team was eager to catch up on time and remove unnecessary events from the schedule, but the president was uneasy. There was still one more commitment on the schedule: a meeting with a local Boy Scout who had written months earlier, hoping to shake his hand. There were no cameras. No press. No political advantage. But Reagan insisted we go. He had made a promise, and to him, the boy mattered. That moment mattered. Reagan believed in showing up, especially for those with no influence, no power, and nothing to offer in return.

And then there was the time I asked him how he avoided nerves before delivering a major address, one that would become one of the most widely broadcast speeches of his presidency. “How do you not get nervous?” I asked. He smiled, recalling his early days as a radio announcer, sitting alone in a windowless booth, narrating baseball games from a wire service to a large audience of listeners. “I remember the guys at the barber shop would always have the radio on. I knew they’d be listening to the game, so I just imagined I was talking to them,” he said. That was the key. He spoke to the world the same way he spoke to a friend or neighbor.

When I first joined the White House, I was young and driven, eager to help the president capitalize on his political mandate. So were many of my colleagues. But Reagan taught us a crucial lesson that’s in short supply today: In a healthy democracy, everyone needs a way to leave the room with dignity. He’d tell us during negotiations, “Let the other side share in the win.” While today’s culture of outrage and polemics insists on total victory, humiliation, and the viral takedown, Ronald Reagan took a more civil path. “If you get 80 percent of what you want,” he’d say, “take it—and come back to try for the rest later.” Even after tough negotiations with congressional opponents, he reminded us that the people on the other side of the table were elected by Americans, too.

Nowhere was this more evident than in his relationship with Tip O’Neill. The two men were fierce political adversaries: Reagan, the conservative standard-bearer, and O’Neill, the liberal defender of the New Deal order. Their debates were fierce. But after hours, over drinks at the White House, they traded jokes like old friends. After one particularly bruising battle, Reagan called to smooth things over. “That’s politics,” O’Neill replied. “After 5 o’clock, we’re friends.” From then on, Reagan would grin and ask, “Tip, is it 5 o’clock yet?” and adjust his watch accordingly.

Their friendship wasn’t a quaint relic of a gentler time. It was an act of devotion to the foundational values of America, and an example of how to disagree without despising and debate without dehumanizing.

Today, that devotion is slipping away. When young men start to believe that violence is the only way to be heard, it is because we’ve failed to offer them a better alternative. We’ve ceded too much ground to cynicism, spectacle, and tribal rage. Reagan’s example reminds us that decency is powerful. And believing in renewal and the goodness of others isn’t naïve—it’s an essential value to keep a free society together.

If we want to change the culture, we need stories that elevate rather than inflame. We need human connection that reminds us of our collective character, grace, and quiet strength. We need to teach our young people how to lose without rage, disagree without contempt, and lead without cruelty.

We need stories that begin and end with the simple conviction: Aren’t people wonderful?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.