The Crisis of Liberalism

Liberalism is in crisis. Its defenders, who see liberalism as a bulwark against tyranny, fear that illiberalism now threatens to overwhelm liberal democracy. Its critics, who say liberalism is a failure that erodes community and tradition, welcome a “post-liberal” order.

Today’s liberalism debate gives the false impression that this crisis is somehow new. In fact, it is as old as liberalism itself: Liberalism has always been defined in part by the argument over the nature and limits of its own identity. Since the middle of the last century, political discourse has been consumed by questions about the virtues and vices of liberalism—from the “fusionist” project to balance freedom and tradition to the republican revival among historians and political theorists to “communitarian” critiques to more recent debates about deliberative democracy.

Today’s critics of liberalism seem to labor under the illusion that they are the first to recognize that liberal society does not provide a substantive moral consensus about the highest good—ignoring intellectual traditions that might help them articulate a humane alternative. Liberalism’s defenders, meanwhile, ignore the fact that individualism does not satisfy the basic human need for belonging. Thus they dismiss the most trenchant criticisms of liberalism, depriving themselves of the resources helpful for a defense of liberal democracy.

What passes for rational debate over liberalism frequently amounts to rival groups shouting past one another—a mutual misunderstanding that gives way to conflict. At its worst, today’s debate offers little more than a performative confirmation of one of the most piercing criticisms of liberalism itself: that liberal discourse masks, rather than resolves, the substantive disagreements that divide us.

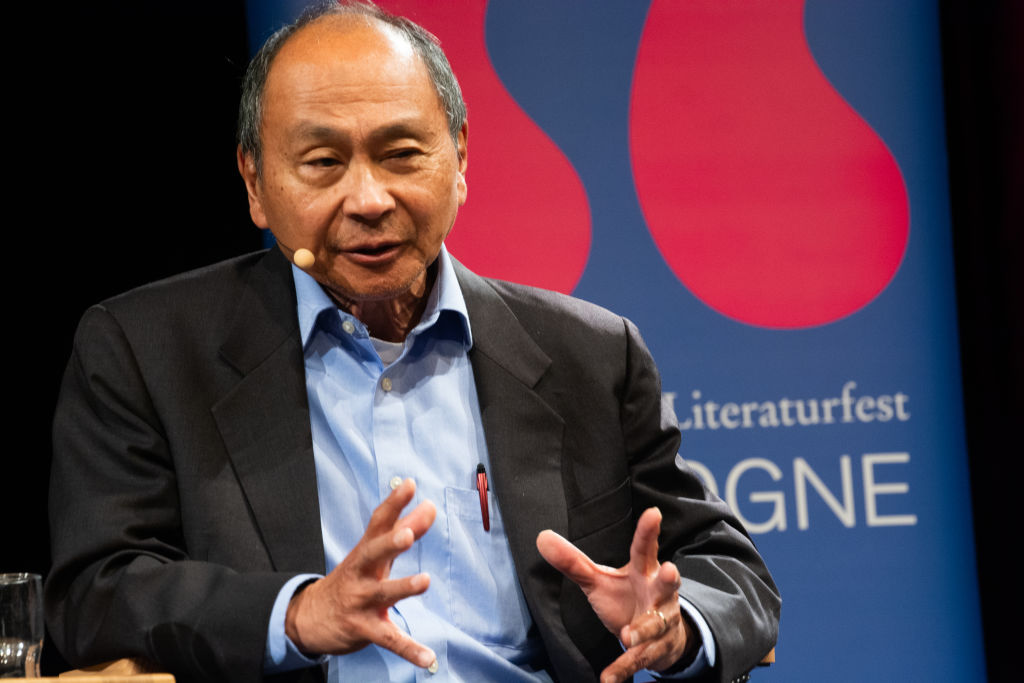

In this disheartening context, we should welcome Francis Fukuyama’s book Liberalism and Its Discontents. Its timely defense of liberalism is refreshingly innocent of the limitations described above. Fukuyama places the debate within a historical context that enriches rather than impoverishes. In going back to the origins of liberalism, he learns from, even while rejecting, many of the most substantive criticisms of liberal theory.

Fukuyama’s defense of liberalism—what he calls, following Deirdre McCloskey, “humane liberalism”—will challenge and inform, if not always persuade, those who do not share his starting premises, not least because the criticisms he engages will be recognizable by his opponents as criticisms. Yet Fukuyama’s argument is not without its own limitations, which hamper an otherwise urgent and compelling case for liberal democracy today.

A Plea for Moderation

Liberalism, for Fukuyama, is not a contemporary political ideology but a foundational doctrine. It asserts “the limitation of the power of governments through law and ultimately constitutions, creating institutions protecting the rights of individuals living under their jurisdiction.”

The doctrine arose amid the ruins of Europe’s wars of religion as a way to govern religiously diverse societies by “lowering the sights” of politics. Liberalism made peace with irreconcilable disagreements about the highest good by making peaceful coexistence the highest political good. A liberal society requires and promotes tolerance, civility, and the equal protection of human dignity.

Fukuyama concedes that liberalism has opened itself up to substantive criticisms from left and right. Rather than abandoning liberalism, however, he offers three reasons for revitalizing it.

The first is practical: Liberalism provides the most effective and humane way to govern diverse societies. Alternatives tend toward tyranny.

The second is moral: Liberalism protects human autonomy, our capacity for moral choice. Rather than a modern threat to tradition, Fukuyama sees autonomy as basic to the West’s religious inheritance and indeed to the human person.

The third is economic: Liberalism protects the right to property, to transact, and to contract. For this reason, liberal societies have always been associated with economic growth and modernization—a process that, Fukuyama argues, is cause and effect of the autonomous individualism on which liberalism depends.

This last point is more subtle and important to Fukuyama’s overall argument than first meets the eye. Liberalism, he argues, though universal in its aspirations, is not an ahistorical dogma. It’s a historical achievement—the product of a particular and contingent set of socioeconomic developments in Western Europe. That makes it no less worthy of defense:

One of the enduring challenges of human societies is the need to move beyond kinship as a source of social organization towards more impersonal forms of social interaction … So while liberal individualism may be the historically contingent by-product of Western civilization, it has proven to be highly attractive to people of varied cultures once they are exposed to the freedom it brings.

Here we can hear echoes, and perhaps refinement, of the liberal Hegelianism on display in Fukuyama’s best-known book, The End of History and the Last Man. Liberalism is not a set of self-evident truths universally recognizable on the basis of pure reason alone, but a product of history—a goal toward which all peoples can and should seek to advance.

The central thesis of Liberalism and Its Discontents is that liberalism has become a victim—not of its own success, as Notre Dame professor Patrick Deneen has charged—but of its own excess. In effect, Fukuyama offers a reflection on the Aristotelian insight that the vice of a given political regime is its virtue taken to an extreme, as when democracy devolves into demagogy.

The book explores how and why liberalism has been carried to false extremes by those who have radicalized its core commitments to freedom, autonomy, and equal dignity—and what can be done to rein it in. Fukuyama thus seeks to save liberalism not only from its critics but from itself. The book concludes, “Recovering a sense of moderation, both individual and communal, is therefore the key to the revival—indeed to the survival—of liberalism itself.”

Liberalism, Left and Right

Although he believes the more immediate, political threat to liberalism today comes from the far right, Fukuyama argues that the crisis of liberalism derives from left and right radicalizations of the liberal tradition.

Take, for instance, the “neoliberal revolution” of the Reagan-Thatcher era. The neoliberal agenda was rooted in liberal insights about the “superior efficiency of markets” and the “moral hazards” often created by government programs intended to help people, according to Fukuyama. But these insights transformed “into something of a religion, in which state intervention was opposed as a matter of principle.” This, in turn, gave rise to a set of policies that “promoted two decades of rapid economic growth,” but which also “succeeded in destabilizing the global economy and undermining its own success.”

Fukuyama concludes that, whatever their benefits, neoliberal policies also produced “the world that emerged by the 2010s; in which aggregate incomes were higher than ever, but inequality within countries had also grown enormously.” The ensuing instability—made worse by wars and refugee crises—“paved the way for the populist reaction that became clearly evident in 2016 with Britain’s Brexit vote and the election of Donald Trump in the United States.”

Liberals on the right carry liberal individualism to a distorting extreme—aided by economic theories that take the “selfish individual” and its preferences as basic. This kind of individualism, Fukuyama emphasizes, is not “wrong” so much as “incomplete,” ignoring the “historically contingent” nature of individualism as well as the profound human craving for “the bond of community and social solidarity.”

Meanwhile, a liberalism of the left values “a different type of autonomy centered around individual self-actualization.” It, too, starts from liberal premises—e.g., the importance of freedom of choice, the need to protect individuals against oppressive forms of social organization—but radically evolves into “identity politics, versions of which then began to undermine the premises of liberalism itself.”

If neoliberalism fetishizes the “selfish individual,” left liberalism “absolutizes” the “sovereign self” and its choices “over all other human goods.” Autonomy here means not the freedom to buy and sell, but the “recovery of that authentic inner self, and escape from the social rules that imprisoned it.” This conception of autonomy, Fukuyama argues, is “theoretically objectionable” because it considers the human person free only when unfettered from “all prior loyalties and commitments.”

Practically, Fukuyama observes, the “sovereign self” wound up reinforcing the countercultural movements of the 1960s and ‘70s, contributing to a therapeutic culture of “self-care” and “self-actualization” that exacerbated “liberalism’s tendency to weaken other forms of communal engagement.” In this way, by taking autonomy to an extreme, liberalism on the left helped erode “virtues like public-spiritedness that are needed to sustain a liberal polity overall.”

Taken together, Fukuyama warns, both radicalizations of liberalism serve to “delegitimize existing institutions,” creating socioeconomic conditions that threaten liberal democracy.

Illiberalism, Left and Right

Fukuyama is hardly the first to observe the corrosive effects of liberal extremism on the social fabric. On the contrary, that is the central thesis of the “communitarian” critics, such as Michael Sandel, Michael Walzer, and Alasdair MacIntyre, all of whom he favorably cites. What is distinctive—and counterintuitive—about Fukuyama’s argument is that he takes liberalism to be the solution rather than the problem. The radicalized forms of liberalism open the doctrine up to criticisms that ultimately “fail to hit their target,” insofar as they “amount to a charge of guilt by association,” he argues.

These criticisms begin from correct premises and highlight real problems but fail to show why liberalism itself must be abandoned. In fact, Fukuyama maintains, these arguments have merit because they appeal to core liberal commitments, such as freedom, equality, and human dignity. Hence the answer to these criticisms “is not to abandon liberalism as such, but to moderate it.”

Take critical theory. Fukuyama concedes that it is often “popularizers and political advocates,” not “serious intellectuals,” advancing the theory. But critical theory itself “made a serious and sustained critique of liberalism’s underlying principles.” Fukuyama insists we should examine the theory’s origins to determine what it gets right—such as the insight that, historically, certain minority groups have been marginalized by the dominant liberal order—and where it goes astray, for instance by trying to replace liberalism “with an alternative illiberal ideology.”

Similarly for right-wing critiques of liberalism, such as those advanced by self-described “national conservatives,” Fukuyama concedes that nations are “important not just because they are the locus of legitimate power and instruments for controlling violence. They are also a singular source of community.” Liberals ignore this at their peril. “If liberalism were to be seen as nothing more than a mechanism for peacefully managing diversity without a broader sense of national purpose, that could be considered a grave political weakness.”

Nationalism, however, radicalizes the need for collective belonging. A national identity based on “fixed characteristics like race, ethnicity, or religious heritage,” risks transforming into “a potentially exclusionary category that violates the liberal principle of equal dignity.” Instead, a nation needs a “positive vision of a liberal national identity,” which “should be a point of pride” for all citizens. By shying “away from appeals to patriotism and cultural tradition,” liberals have allowed this territory to be claimed by the extreme right.

Here the politics of identity and nationalism began to mirror one another. Both start from an insight about the importance of mutual recognition within the social whole and point to liberalism’s failure to answer to this basic human need. (It is no coincidence that the themes of identity and recognition, treated at length in Fukuyama’s previous book, Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment, were developed by the Russian-born French Hegelian Alexandre Kojève—the inspiration for Fukuyama’s end of history thesis.) But identity politics and nationalism carry this insight to illiberal extremes. They err, Fukuyama argues, by mistaking liberalism’s historical failures for irredeemable flaws of liberal doctrine.

Rather than jettisoning liberalism, Fukuyama urges us to learn from such criticisms, articulating a humane liberalism responsive to the need for recognition and belonging while striving to instantiate the ideals of freedom and equality.

Modern Science’s ‘Distinctive Cognitive Mode’

In the first half of Liberalism and Its Discontents, Fukuyama proves a reliable guide through the history of modern political thought. He is on firm ground when arguing that extreme forms of liberalism have proved theoretically objectionable and practically destructive. And his attempt to salvage liberalism from its critics—by showing how, at their best, their critiques presuppose liberal principles themselves—is among the strongest parts of the book. The same cannot be said for his discussion of scientific rationality.

“From its earliest beginnings,” Fukuyama argues, “modern liberalism was strongly associated with a distinctive cognitive mode, that of modern natural science.” This “cognitive mode” is characterized by a belief in “an objective reality outside the human mind, which human beings can gradually understand and ultimately come to manipulate” through the experimental method of modern natural science. According to Fukuyama, this cognitive mode provides the basis for the liberal commitment to rational discourse—with its “broad normative preference for empirical rigor”—as well as “the project of mastering nature through science and technology, and using the latter to bend the given world to suit human purposes.”

But, beginning with Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure who influenced such French “poststructuralists” as Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida, a critique of scientific rationality has called both into question. As Fukuyama tells it, these thinkers, along with influential figures such as Michel Foucault and Edward Said, have attacked modern science for its association with “existing power structures” and western imperialism—thus denying the possibility of rational discourse.

Together with digital media that promote disinformation, Fukuyama argues these critiques have contributed to a “deep cognitive crisis” in modern democracies—a crisis worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic, during which the right has “produced a mirror-image” of the postmodernist critique of liberalism and “its associated cognitive methods.”

It would be difficult to deny the historical connection between the rise of liberalism and modern science. And modern societies are, indeed, in the midst of an epistemic crisis that threatens the foundations of liberal democracy, predating but exacerbated by COVID-19. Understanding the nature of this crisis is an urgent task.

But readers familiar with either the history and philosophy of modern science or the writings of so-called “postmodern” thinkers will not recognize Fukuyama’s characterizations as much more than caricatures.

Which Scientific Method?

Fukuyama’s Baconian account of scientific rationality ignores considerable scholarly literature that has questioned the influence of Francis Bacon’s ideas on the historical development of modern natural science. Meanwhile, Fukuyama identifies modern science with a particular “scientific method”—which he associates, somewhat indiscriminately, with a “battery” of concepts such as “induction,” “verifiability,” “falsification,” and “causal inference.” Yet, these are rival philosophical interpretations of science, rather than neutral descriptions of a single “scientific method.”

No less puzzling is Fukuyama’s association of this cognitive mode with a belief in an “objective reality outside the human mind.” This belief—which philosophers call “realism”—certainly has been rejected by postmodern theorists. But it was the modern philosophers associated with the Scientific Revolution itself—notably René Descartes, David Hume, and Immanuel Kant —who revived skepticism, in contrast to the realism of medieval Aristotelianism that held sway until the Renaissance.

Less controversial is Fukuyama’s association of modern science with the “project of mastering nature through science and technology, and using the latter to bend the given world to suit human purposes.” Generally, it would be difficult to deny the link between modern science and technological dominance. But here, too, Fukuyama’s account runs roughshod over complex conceptual and historical territory.

First, the technological mastery of nature we associate with modernity predates the scientific revolution of the 17th century—beginning in the Renaissance, if not the Middle Ages. Second, the scientific revolution itself began within those branches of natural science, such as astronomy, least connected to technological innovation. Third, the industrial revolution that began in the next century—which made possible a new kind and degree of technological control of nature—was more attributable to advances in engineering techniques, such as the flying shuttle, the spinning jenny, the spinning mule, and the puddling furnace, than to scientific discoveries. In fact, it was not until well into the 19th century that natural science came to be intimately linked to industrial production and technological innovation, especially with the rise of electromagnetism and modern chemistry.

All of this suggests that the identification of science with technological mastery is, at best, one of many contestable interpretations. Defending it would require explaining or accommodating these recalcitrant historical facts rather than sidestepping them.

Rationalism vs. Rationalism

Liberals have historically advanced the Baconian interpretation of science that Fukuyama defends. From the Enlightenment philosophes to early 20th century progressives to today’s techno-utopians and “follow-the science” ideologues, many liberals on left and right have reached for scientific rationality as a tool to master nature and society. One might argue that it was this interpretation of science, more than modern science per se, which plays such a large role in liberal theory.

Yet critical theorists and “postmodernists,” from Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno to Foucault, have unmasked this worldview for the scientific ideology that it is. In this sense, they are heirs not so much to Saussure’s linguistic conventionalism as of the Romantic critique of Enlightenment rationalism alongside thinkers such as Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger.

This, however, does not mean reading these critics of rationalism as asserting “a radical subjectivism that rooted knowledge in lived experience and emotion,” as Fukuyama suggests.

Yes, Foucault, along with Adorno, Horkheimer, Derrida, and others, scrutinized rationalism. They did so not because they prioritized “lived experience and emotion” but recognized subjectivism and rationalism as flipsides of the same coin—ambivalent inheritances of modern thought.

It is worth observing, here, that not only “postmodernists” and critical theorists have taken the rationalist worldview to task. Any number of thinkers—including liberals and non-liberals, leftist and rightists, theists and atheists—have homed in on the dangers and limits of Enlightenment rationalism’s rigid formalism. Thus Hegel and John Henry Newman, R.G. Collingwood and C.S. Lewis, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Hans-Georg Gadamer, Michael Polanyi and Friedrich Hayek, Hannah Arendt and Jürgen Habermas, Charles Taylor and Alasdair MacIntyre—none of these thinkers could be described as valorizing “radical subjectivism.” If they and their postmodern counterparts are wrong to reject rationalism, Fukuyama does not tell us why.

Where some of these thinkers (or at least many of their imitators) do go wrong is in reducing scientific rationality—or even human rationality—to rationalism. Ironically enough, however, this is the very error that Fukuyama himself commits in his characterization of modern science’s “distinctive cognitive mode.” Had he instead rejected rationalism as a perversion of reason, Fukuyama could have given a far more persuasive defense of liberalism against those critiques which needlessly discard rationality as such.

Rationalism and Its Discontents

This failure to adequately engage critiques of rationalism is closely connected to a second flaw in Fukuyama’s argument: his neglect of a critique of liberalism that implicates the very conception of rationality he espouses.

Liberalism is often understood to entail an instrumentalist view of politics: that politics “has the function of bundling together and pushing private interests against a government apparatus specializing in the administrative employment of political power for collective goals,” as Jürgen Habermas describes it. Politics, in other words, is an instrument—a kind of neutral technique—for the fair management of competing private interests.

From there it’s a short step to an overtly technocratic view of politics, in which, rather than rational deliberation within the public sphere, experts and bureaucratic managers work together to administer goods and services to the public. The animating question of politics then becomes: What is the most efficient mechanism for the allocation of goods and services? “Disinterested” expertise here functions to facilitate efficient management, while masking substantive disagreements about the ends politics means to serve.

Politics on this view is simply a means—a necessary evil—entered into by self-interested individuals in order to avert violent conflict. Welfare state liberalism may thus be understood as a further stage along the same process of rationalization, in which the state protects individuals from the maleffects of economic modernization while guaranteeing as many people as possible enjoy its benefits.

According to this line of argument, liberalism winds up undermining the goals of liberalism itself by producing a bureaucratic state, vulnerable to capture by special interests, that saps liberal societies of the ethical substance on which they depend. The result is a depoliticized citizenry whose role in the political process has been reduced to that of passive consumers, “with only the right to withhold acclamation” of “administrative decisions” made largely without their participation, as Habermas puts it.

Historically, versions of this critique have been advanced by liberalism’s enemies—such as the German political theorist and Nazi collaborator Carl Schmitt, who is popular among today’s post-liberal conservatives. But it has also been hinted at by liberalism’s friends, such as the German sociologist Max Weber. More recently, political theorists from MacIntyre to Taylor to Arendt to Habermas himself have pointed to the instrumental view of politics as liberalism’s fatal flaw—an idea echoed by some of today’s critics. For instance, Patrick Deneen dismisses the American Constitution as the “applied technology” of “liberal theory.”

It is surprising, given his fair-handed treatment of other criticisms—not to mention his references to many of these very figures—that Fukuyama does not address this critique in Liberalism and Its Discontents. He might have argued that technocratic liberalism was yet another case of liberal doctrine taken to a falsifying extreme, thus misleading critics into throwing out the liberal baby with the technocratic bath water.

Developing such an argument, however, would have required disentangling liberalism from the very “cognitive mode” with which Fukuyama explicitly seeks to link it. Here the critiques of rationalism he rejects—including but not limited to those advanced by critical theorists and “postmodernists”—could have proved useful for articulating a more humane conception of human reason. And that could have provided the resources for a non-technocratic politics to help revive political institutions and buttress them against illiberal forces.

Beyond Technocratic Liberalism

What might such a non-technocratic politics look like? One possibility hinted at by Fukuyama is provided by the tradition of civic republicanism, which is traceable to this country’s founding. Some historians have argued that it was republicanism, rather than liberalism, that inspired the American Revolution and constitutional system.

Looking to a classical concept of citizenship, republicanism sees politics as an expression of our political nature rather than an instrument for managing individual competition. It emphasizes civic virtue and the shared obligation of self-rule over the freedom to pursue private self-interest. Yet, though at odds with liberal individualism and the instrumental view of politics it implies, republicanism does not thereby abandon liberty or the institutions established to protect it. It provides an alternative rationale for them instead. On this view, liberal institutions, such as limited government and the separation of powers, do not just protect individual rights. They also make space for the practice of self-government—a kind of politics that demands both liberty and commitment to the common weal.

Liberalism and Its Discontents contains at least one favorable reference to “civic republicanism,” and Fukuyama himself adopts republican rhetoric at times, notably in his discussion of left and right radicalizations of liberalism. Pursuing this line of thought further would have helped his case for liberalism, providing a stronger basis for defending our institutions against illiberal threats.

For instance, from a republican standpoint, the problem with left and right radicalizations of liberalism is not that they pervert liberalism, but that they spoil civic life. The “selfish individual” and the “sovereign self” are both inimical to the public-spirited citizen demanded by the ideal of self-government. As for left and right critics of liberalism, where many of them go astray from the republican standpoint is in identifying our political inheritance exclusively with liberalism. This leads them to reject liberal individualism and the technocratic society to which it gives rise but also liberal institutions themselves.

But these institutions, as Fukuyama rightly emphasizes, are the best known way to promote human flourishing in a diverse society. By identifying our political inheritance too narrowly with liberal individualism, however, Fukuyama himself risks committing the same error as liberalism’s critics. He leaves inadequate space for a non-technocratic account of politics that could provide a positive vision of political community for liberal institutions—and a standpoint from which to criticize the extreme forms of liberalism and illiberalism.

Such limitations notwithstanding, Liberalism and Its Discontents is an achievement—a readable and humane defense of liberalism that is needed today more than ever. All the more remarkable is the fact that all this is accomplished in 154 pages of crisp prose. Fukuyama’s is not simply one more argument for liberalism—it should be the starting point for a reinvigorated debate about the future of the liberal order.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.