Private elementary and secondary schools are taking it on the chin. Since the COVID-19 pandemic shut down schools across the land, more than two dozen schools have closed for good. While thousands of other scrappy, beloved community institutions are scrambling to hold on, private schools are also under the microscope. Earlier this month, it was reported that elite prep schools like Saint Andrew’s (which President Trump’s youngest son attends) had received Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans. The backlash was justifiably swift.

The PPP brouhaha is just one of the recent events complicating efforts to support struggling private schools (for another example, see here). After all, no one should be making the case to bail out deep-pocketed, elite private schools (with tuitions nearing $50,000 and endowments in the tens of millions). But contrary to public misperception, such schools are only a tiny sliver of the nation’s 35,000 private schools. Indeed, thousands of private schools are a tuition cycle away from dire financial straits—or closure.

Bellwether Education has reported that, in 2011-12 (the most recent year with nationwide data), 60 percent of private schools charged less than $6,000 a year in tuition. In diocesan Catholic schools, which comprise the largest share of private schools, the average K-8 parish school charged tuition of $4,841 in 2017-18 (and enrolled about 240 students). Such costs are dwarfed by annual outlays on the nation’s public schools, which collect an average of $13,000 to $14,000 a year per pupil—with the amount higher still in urban centers like New York and Chicago.

Not only are most private schools relatively inexpensive, but the evidence suggests that they’re putting those dollars to good use. Dating back to James Coleman’s seminal research from decades ago, the evidence suggests that students who choose to attend private schools reap significant benefits from doing so. More recent research continues and extends Coleman’s findings. As EdChoice has reported in a summary of the research on private-school choice programs, 11 out of 17 gold-standard studies on academic performance found positive outcomes, four out of six empirical analyses on education attainment were positive, and 28 out of 30 studies showed increased parental satisfaction.

If these schools close, the negative impacts extend beyond the students and families that attended those schools. If a sizable share of the 5 million students who attend private K-12 schools suddenly flood into local public schools, the costs would be significant. EdChoice’s Robert Enlow has calculated that if only 10 percent of private school students return to the public system, the combined state and local cost would be $6.7 billion a year. If 30 percent of private school students were suddenly to enroll in public schools, the cost would be $20 billion a year.

Then there’s the seismic impact of losing vital community institutions. As Notre Dame scholars Nicole Garnett and Margaret Brinig studied the closure of Catholic schools across the dioceses of Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Chicago in their 2014 book Lost Classroom, Lost Community and found that the loss of these schools led a significant loss of social capital and an overall decline in community cohesion. Garnett and Brinig found that, between 1999 and 2005, the presence of an open Catholic school in a police beat was consistently associated with a statistically significant decrease in crime (the crime rate in police beats with Catholic schools was, on average, at least 33 percent lower than in police beats without them).

Congress rightly stepped up to help preserve all manner of small enterprises across the land, from hamburger stands to hair salons. Federal aid during a pandemic is less a bailout than life support provided in response to a purposeful shutdown of the economy. Schools were shuttered in the service of public health. That’s fine. Public schools are facing budget shortfalls and will continue to need additional assistance, but they also have known they would continue to receive revenues throughout the crisis, and that they’ll come back to new revenues in the fall. Tuition-dependent private schools know no such thing. Their survival is entirely dependent on whether and when they’re allowed to open.

In the meantime, as Congress seeks to bolster state governments and local school systems in the next round of aid, it should take care to ensure that private schools don’t get left behind. While they were eligible for PPP loans, private schools are not used to collecting federal funds. Unlike big nonprofits, they don’t have in-house lawyers or grant writers and financial advisors. Thus, they generally weren’t equipped to take advantage of PPP loans for private small businesses. And, unlike local districts, they can’t be sure that they’ll still be around whenever things start to return to normal. Thousands of private schools are in mortal peril through no fault of their own, and it would be a grave loss to the nation if they were to vanish. Congress should act accordingly.

In the HEROES Act, the House Democrats’ opening bid included almost $60 billion in K-12 funding and $900 billion more for state and local government. Given that more than a quarter of state revenue flows into K-12 schools, that would earmark another $200 billion-plus for public school systems. In short, the House proposal envisions more than $250 billion for public schools (though a final deal is likely to be for significantly less). Whatever the numbers turn out to be, Congress would do well to set forth a modest, additional pool of funds to support hand-to-mouth private schools.

About 10 percent of all students—and about 5 percent of low-income students—attend private schools. Let’s work from the lower of those figures. If another aid bill passes, Congress should include a provision that allocates an amount of aid for private K-12 schools that is the equivalent to 5 percent of the aid set aside for public schools. If combined aid for public schools winds up at around half the House’s projected level, say $120 billion, that would suggest investing about $6 billion in a preservation fund for private schools. These funds should not come at the expense of support for public K-12 schools—they should accompany it.

Now, concerns about federal funds subsidizing ritzy private schools are certainly fair. So, two criteria should be required of schools seeking aid. First, a school’s 2019-20 tuition should be no higher than local public school per pupil spending. Second, schools with any kind of sizable endowment should be ineligible. For those worried about church-state issues, there’s no need to wade into complicated discussions of Trinity Lutheran; religious institutions were eligible for PPP loans, that template should apply here.

School districts will need federal support, but they can also count on a guaranteed stream of tax dollars going forward—regardless of when they open their doors. Thousands of small, irreplaceable private schools will not have that backstop. It’s time for Congress to do what it can to provide one.

Frederick M. Hess is director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute. Brendan Bell is program manager at AEI.

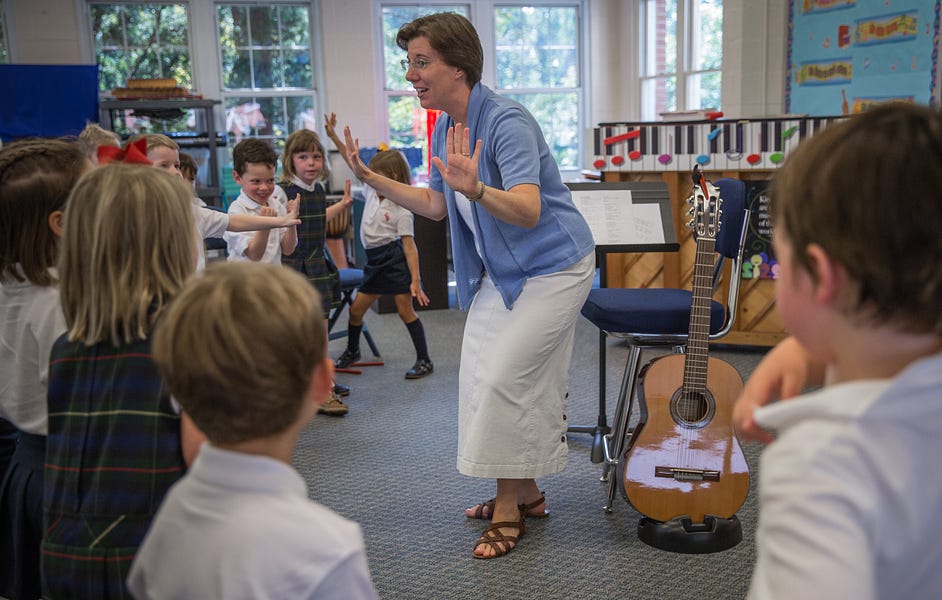

Photograph by Evelyn Hockstein/Washington Post/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.