As the coronavirus pandemic spread throughout the world this year, we quickly learned that the elderly, and particularly those with pre-existing conditions, are especially at risk of severe complications and death from COVID-19. It’s no wonder that those living in long-term care settings are perhaps the most vulnerable group in society.

Our research at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity shows staggering numbers. There are 5.1 million elderly and disabled individuals who live in long-term care facilities, including nursing homes and assisted living facilities. These individuals represent only 1.6% of the population, but as of May 22, they account for 43% of all COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. And this is likely an undercount; excluding New York state (where COVID-19 nursing home fatality figures do not include those residents who die in the hospital), the average across all remaining states is 53 percent. Based on this metric, those hardest hit include Pennsylvania (69 percent), Ohio (70 percent), New Hampshire (70 percent), Rhode Island (77 percent), and Minnesota (81 percent).

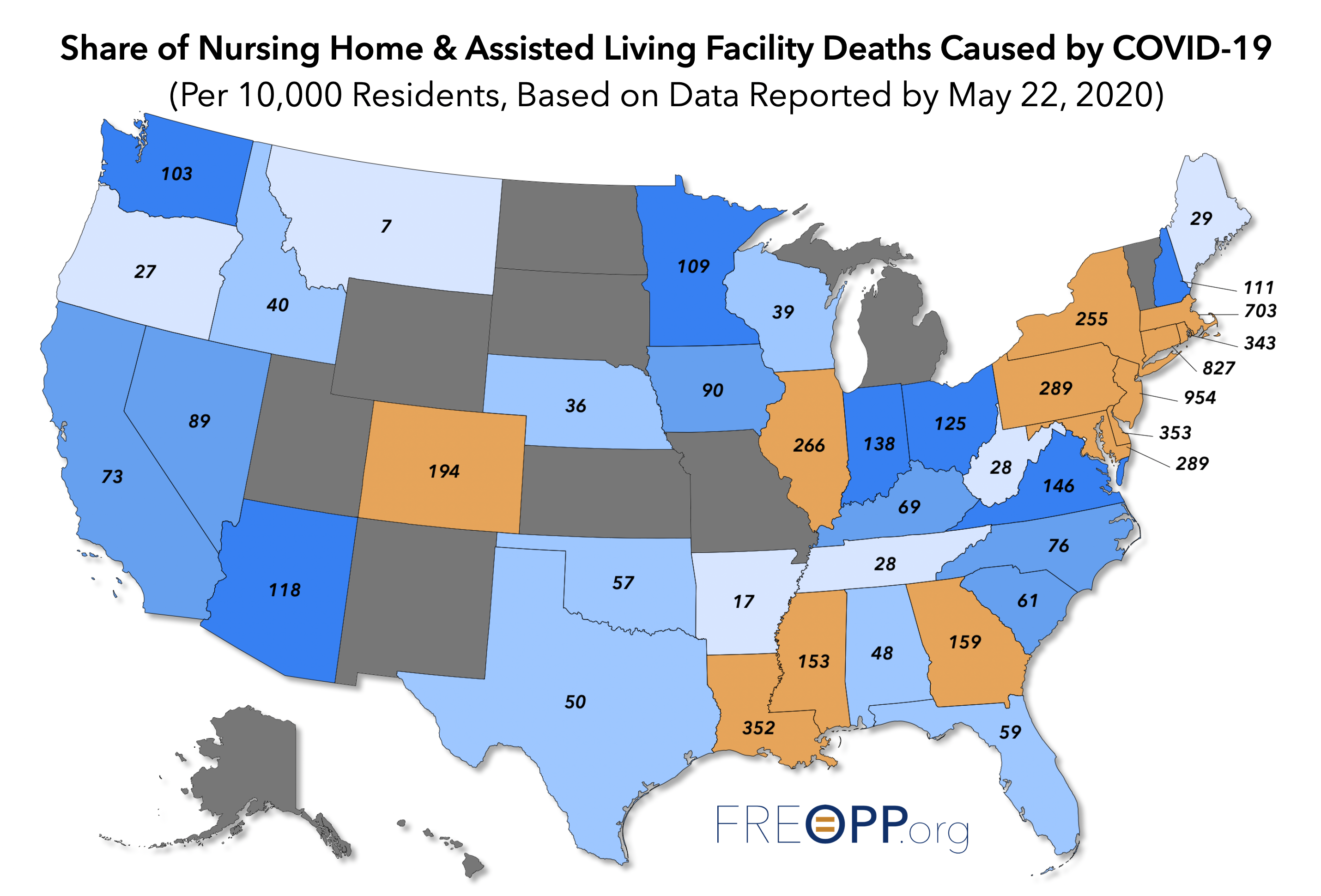

We can also analyze fatality data in long-term care facilities by looking at the number of residents who have died as a share of the total population in those facilities. The fatality rates in the northeast are particularly grim. Coronavirus deaths per 10,000 residents in Massachusetts and Connecticut stand at 703 and 827, respectively. And at 954 fatalities per 10,000 residents, nearly 10 percent of all long-term care residents in New Jersey have died from COVID-19.

The U.S. is not an outlier for nursing home-related deaths due to COVID-19. Researchers at the International Long-term Care Policy Network found that of all fatalities in Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, and Sweden, half were nursing home residents.

With recognition of nursing homes as ground zero for the pandemic, it is important to understand how we got here, so that we can protect our most vulnerable in the future. In the past, our work at FREOPP has focused on how individual states, such as New York, disastrously forced nursing homes to accept hospital patients with active SARS-CoV-2 infections. These tragic decisions amplified an underlying problem: the fractured payment system for long-term care services.

A perfect storm.

Nursing homes were an obvious vulnerable population in the context of COVID-19. The nursing home population is elderly, frail, and suffers from many chronic conditions that lead to severe cases of COVID-19, including cardiovascular disease and diabetes. The congregate nature of these facilities only exacerbates the problem. Nursing homes look and operate much like hospitals, where many residents are confined to a bed and may share a room with another resident. The people who work in nursing homes have close and sustained contact with residents, because they are assisting them with activities of daily living.

The pandemic has further exposed problems that have plagued the long-term care industry: staff shortages, burnout, lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), inadequate sanitation, and poor infection controls. Many personal care staff and nurses work at more than one nursing home, creating the possibility of spreading infection from one facility to another. Perhaps it is not surprising that so many nursing home residents have died from the coronavirus; the CDC reports that as many as 380,000 residents die from infections in long-term care facilities each year.

In other words, the combination of vulnerable population, living together in a congregate setting, with staffing and sanitation problems combined into the perfect storm of infection, illness, and death.

Some people argue that reopening the economy will be catastrophic for public health. But it is eminently possible to safely reopen the economy, so long as we take the right steps to protect the most vulnerable populations.

In the short term, that means rescinding the catastrophic Andrew Cuomo-style orders in states like New Jersey and Michigan that have forced nursing homes to accept infected patients, and instead barring hospitals from discharging infected nursing home residents, as Louisiana has done.

But beyond that we need to address the underlying, 50-years-in-the-making problem of how we pay for long-term care.

Follow the money.

Beginning with passage of the Social Security Act in 1935, the federal government changed the way the poor and frail received assistance, prohibiting payment to public poorhouses in favor of payments to private institutions. From this change, the private nursing home industry was born.

The passage of the Medicare and Medicaid Act of 1965 expanded federal funding of long-term care specifically. While Medicare would cover post-acute care following surgery short-term, Medicaid would become the dominant payer for custodial care, assisting an individual with activities of daily living (e.g., bathing, dressing, transferring in and out of bed, etc.).

As the price of care in nursing homes continued to rise over the ensuing decades, Medicaid solidified its status as the payer of last resort for millions of low-income seniors. Excluding Medicare payment for post-acute care, Medicaid now pays 54% of long-term care nationwide. On average, Medicaid spends more than $70,000 per year to keep an individual in a nursing home.

Payment of long-term care services is a strain on Medicaid’s finances as well. Only about 6 percent of Medicaid enrollees receive long-term care services, but such services account for more than 30 percent of the program’s expenditures. And the aging of the population means the expenditures are likely to increase for the foreseeable future.

At first, the Medicaid statute permitted payment only for institutional care like nursing homes. But the rising elderly population has created a demand for other options like home- and community-based settings. Policymakers have tried to shift recipients toward these options, which are a win-win for both benefit recipients and taxpayers alike, since seniors prefer such settings and they are less costly. Despite these efforts, the bias in long-term care toward nursing homes still lingers.

The bias exists in various ways. Six states provide no Medicaid benefits for assisted living facilities, where seniors live in an environment that promotes independence and self-sufficiency. As for the other 44 states and D.C. that do, seniors can only access such services through a Medicaid waiver program, many of which are in such high demand that states keep otherwise eligible recipients on waiting lists. In fact, the Kaiser Family Foundation reported that those on HCBS waiver waiting lists eclipsed 700,000 people in 2017. And even if you are one of the lucky ones to come off the waiting list, Medicaid will not pay room and board in any home or community based setting.

The institutional bias that persists over 50 years after Medicaid’s inception is obvious when one considers that 62 percent of nursing home residents nationwide are on Medicaid. In some states, the percentage is higher: Alaska, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia all have greater than 70% of residents paying through Medicaid.

The cost pressures on nursing home operators due to high Medicaid case loads mean many nursing homes were teetering on the edge of profitability before the pandemic; Medicaid pays the lowest rates for nursing home care relative to other insurers. As a result, providers must compete for post-acute care residents recovering from procedures like a hip replacement, who pay much higher reimbursement rates through Medicare for a short-term stay. And those procedures were on hold in many places for much of the last few months.

Thin profit margins inevitably affect the quality of care residents receive. There often isn’t enough money to pay for extra staff, leaving existing staff underpaid and overworked. With such working conditions, the potential for elder abuse and neglect increases and infection control diminishes.

These weaknesses arising from a flawed business model have only gotten worse with the pandemic. Shortages of personal protective equipment and sanitation supplies are even greater. Staffs that were stretched to the limit before the virus are strained further when workers become infected or refused to come to work. With the number of patients per staff member increasing, the chances an infected but asymptomatic worker could spread the virus to multiple residents increases as well.

Families are responding by pulling their loved ones out of nursing homes. New move-ins are declining as well, fueled by fears of the virus and restrictions on family members’ ability to visit. Meanwhile, expenses are rising as nursing homes step up efforts to protect residents. The result is nursing homes that were already vulnerable financially have just experienced a shock that many will not survive.

The way forward.

In the short-term, states are targeting emergency funding to nursing homes to hire staff and to purchase PPE and sanitation supplies, in the hopes that the outbreaks can be contained.

It is clear, however, that the long-term care industry will never return to the way things were before. Increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates to nursing homes may provide a temporary boost but is not fiscally sustainable for a program that is already expanding beyond what states can handle. Nursing home closures are inevitable, and consolidation of those that survive is likely. Such disruption and shrinking capacity will collide with Medicaid’s nursing home bias. Without significant changes to Medicaid’s eligibility and benefit structure, Medicaid recipients who would have no choice but to live in a nursing home may not find one available.

As the U.S. population ages, and the demand for long-term care in nursing homes falls, long-term care in home and community settings will take a more prominent role out of necessity. Settings such as assisted living facilities are better equipped to care for Medicaid patients, since their business models attract residents who pay higher rates through long-term care insurance or out-of-pocket payments. However, more flexibility in Medicaid financing is needed to align with these changes and to place individuals in settings most appropriate to their needs. Such a change will yield better health outcomes, and the reduced patient density outside nursing homes may reduce the probability of infection from the next pandemic.

But such changes will not be enough. At some point, we will have to revisit the central role of Medicaid in the funding of long-term care. It is a challenging policy area, not least because of the degree to which it roils state budgets. We could start by offering stronger support to family caregivers, who even today provide more long-term care than the entire corporate long-term care industry.

The COVID-19 pandemic—compounded by the decisions of governors like Andrew Cuomo—has made clear that the U.S. long-term care model is broken. But perhaps that tragedy will spur us to make long-needed reforms to Medicaid that can make long-term care better and safer for generations to come.

Photograph by John Lamparski/NurPhoto via Getty Images.

Gregg Girvan is a health care research fellow at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.