Earlier this month, the New York Times reported that starting in March 2020, the Trump campaign had tricked many donors into signing up to make repeated donations, even when the donor intended to donate only once.

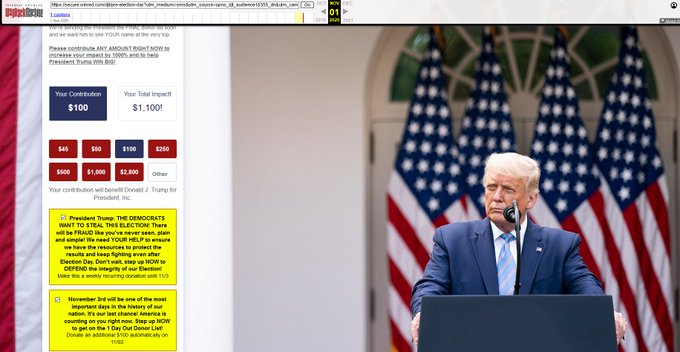

When supporters made donations through the WinRed website, the default setting—a checked box that the user would have to uncheck to opt out—would sign them up to make recurring donations—once a month or (later in the campaign) once a week, at the same dollar amount. The Times told the story of a donor who wanted to make a one-time $500 donation to the campaign but found himself having $500 taken from his account every week. Like many donors, he did not realize he had to actively uncheck a box to avoid recurring donations. The fact that the box in question was well hidden in the fine print did not make it easier. Later, another pre-checked box was added that signed donors up to participate in “money bombs,” days during which additional donations would be automatically withdrawn from their account.

What’s going on here is a type of nudging. For those not familiar with the term, it’s when psychology is used to trick consumers into making choices that the designers of the nudge perceive to be better for the consumers themselves. One example would be when cafeterias and grocery stores are redesigned to make healthy foods more visible, increasing the likelihood that consumers will choose them. With nudging, no choices are actually taken away, nor is the right choice financially subsidized or the wrong choice penalized (as is the case with excise duties), but consumers still become more likely to make the “right” choice.

As a behavioral economist, I did a lot of my doctoral research on nudging. Unlike most people in my field, I am rather skeptical of nudging, and to me, what the Trump campaign did merely emphasizes how dangerous the use and legitimizing of nudging can be. There are several reasons why nudging is problematic, not least because, as it relies on psychological manipulation, it necessarily happens in the dark, without the consent or even knowledge of the affected consumers. Whatever one may say about more heavy-handed nanny state measures like sin taxes, at least they happen in the open.

My fellow behavioral economists may protest that what the Trump campaign did cannot be considered a nudge, since the nudge was meant to benefit the campaign, not the donor. The precise definition of nudging requires that it is done for the benefit of the individual being nudged. But who decides what is beneficial? Who decides what the best option is?

In the end, what the Trump campaign did was basically to add a default option nudge to its fundraising website. The default option benefited the campaign, but they knew participants would be far less likely to choose it without the nudge. Nudges like this one are used all the time: Many employers, including public employers, today offer “opt-in” rather than “opt-out” pension contribution schemes, meaning you will automatically be enrolled and have a contribution deducted from your paycheck unless you actively make the choice not to be. While what the Trump campaign did was arguably nudging at its worst, one cannot deny the similarities between the actions of the campaign, and the actions of government actors trying to steer the choices of individuals “for their own good.”

It is unsurprising the nudge used by the Trump campaign was so successful. My own research suggests that the default option nudge tends to work especially well with people who make their decisions in a rush, without paying much attention. It is easy to see how fired-up Trump supporters at rallies may have used their phone to donate money and missed the fine print. Even people who are normally attentive can be made inattentive by surges in emotions, such as may occur at a rally, or while watching a debate. The fact that they trusted Trump and his campaign made the nudge even more likely to work; their guards were already down. My research also suggests that nudges work better when the stakes involved are small. If you’re spending (or donating) pocket change, you’re far more susceptible to all kinds of nudges and manipulations because the amounts are small, making it seem not worthwhile to think hard about the decision for a prolonged period of time (or read the fine print).

The real evil genius, however, lay in the fact that donating money toward a cause serves to make people more emotionally invested in that cause. Tricking people into donating the maximum federal limit, when they had intended to donate only a few hundred dollars, may very well have made them more invested in Trump’s victory. To admit to themselves and others that they had no intention to donate that much money would mean effectively admitting that the Trump campaign defrauded them, which means the pesky liberals and NeverTrumpers were right (at least on that count). For many people it’s easier to invent an ex post justification, telling themselves that they were absolutely going to donate the federal legal limit anyway, so they don’t really mind at all.

One common argument in favor of nudges, and default option nudges in particular, is that there always will be a default option. Either you are enrolled, or you have to enroll. So why not make it the “better” option? Why is that more manipulative? Furthermore, companies use psychology all the time to make people spend more, including by setting the more expensive option as the default, so why is it so bad if the government uses (or mandates that it be used) for good? There are already several examples of governments, local and federal, using nudging to help consumers make better decisions: The Affordable Care Act utilized several forms of nudging, including auto-enrollment (with an opt-out option) for workers in firms with over 200 employees.

Mike Bloomberg did not ban anyone from consuming as much soda as they wanted, but he tried to ban the Big Gulp and thus force consumers to buy soda in smaller units. On a local level, the city of Berkeley, California, recently banned shops from placing candy in the checkout lanes. No consumer is banned from buying candy, just like no consumer would have been banned from drinking soda if Mike Bloomberg had had his way, but nonetheless, fewer would do so—it’s basic psychology. Since these nudges all have goals (i.e. reducing obesity) that virtually everyone can agree are virtuous, and since companies use arguably as much or more psychology to make consumers act the way they want, why is it wrong for governments to manipulate consumers for ‘good’?

The response from nudging skeptics like myself would be that the government must be held to a higher standard of ethics so as to not erode trust, and that if a government is allowed to manipulate its citizens in the dark, the consequences are far more dire than if corporations are allowed to do so, since governments are so much more powerful. The Trump campaign could indeed claim that what it did was no different from what businesses do every day, and it would not be entirely incorrect. Outraged people might respond that campaigns should live up to the ethical standards of government rather than act like businesses, and I would be inclined to agree, but when governments have already reduced themselves to using psychology to trick people into doing “what is best for them,” it becomes harder to find a leg to stand on.

The Trump campaign could even argue that the recurring donations were for the benefit of the donor, just like the nudges implemented and encouraged by both businesses and federal and local governments, since these donations increased the chances of Trump winning the election, which would in turn benefit the donor who would get to live in an America that had been made Great Again. Sure, there might not be any guaranteed individual benefit, but then on the other hand, is there any guaranteed benefit for the individuals who are nudged to reduce their carbon footprint, or to recycle? While nudges were originally pitched as a way to help make it easier for individuals to make decisions that they would like to make and that they would benefit from personally, this original cornerstone has largely been abandoned in recent years with the introduction of these “green nudges”. While these nudges may support commendable goals, the only way that a consumer benefits from them is if all—or the vast majority—of consumers globally change their behaviors. If you are nudged into reducing your carbon footprint while no-one else does the same, your individual benefit will be non-existent. By crossing the barrier from nudging for the individual good to nudging to accomplish what policy-makers consider the “greater good” or even for future as-of-yet-unborn generations, nudging has become all the more problematic from an ethical viewpoint.

What the Trump campaign did was no doubt despicable, and I would argue that campaign laws should be changed to prevent campaigns from abusing the trust of their donors in this way in the future. Most importantly though, this incident highlights that a public debate about nudging and its acceptable uses and limits is long overdue. Policymakers need to recognize that when shady tactics are used by the “good” guys, it becomes easier for bad guys to get away with using them too. Nudging, and behavioral economics as a whole, was developed with the very best of intentions, but that does not prevent it from being weaponized and used in malicious ways.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.