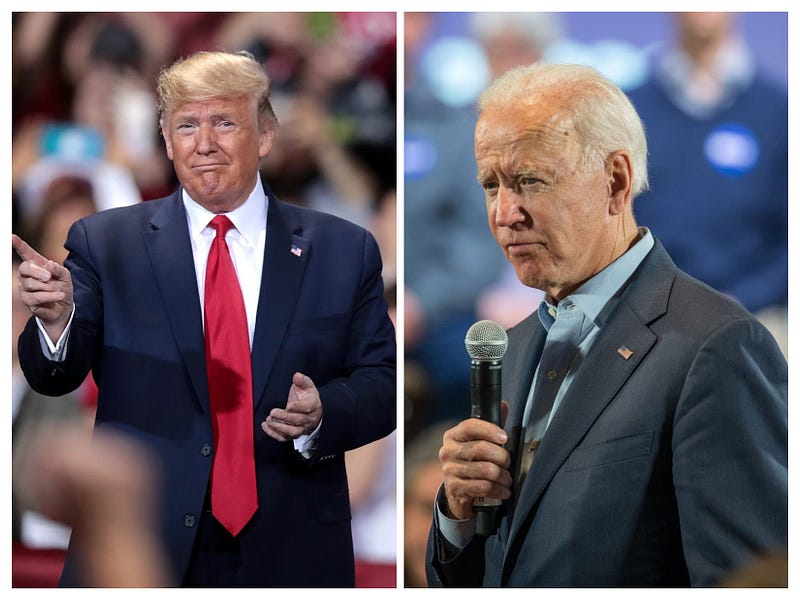

Back in 2008, Barack Obama’s campaign pioneered the use of the web and associated metrics, catching his opponent John McCain flat-footed. It changed the way candidates ran for president. And now, since the pandemic prevents both Donald Trump and Joe Biden from having rallies or other in-person events, the online campaign is pretty much the only campaign.

Not since 2008 have we seen as sharp a contrast in the digital media presence between presumptive nominees. But this time the difference is almost entirely about tone.

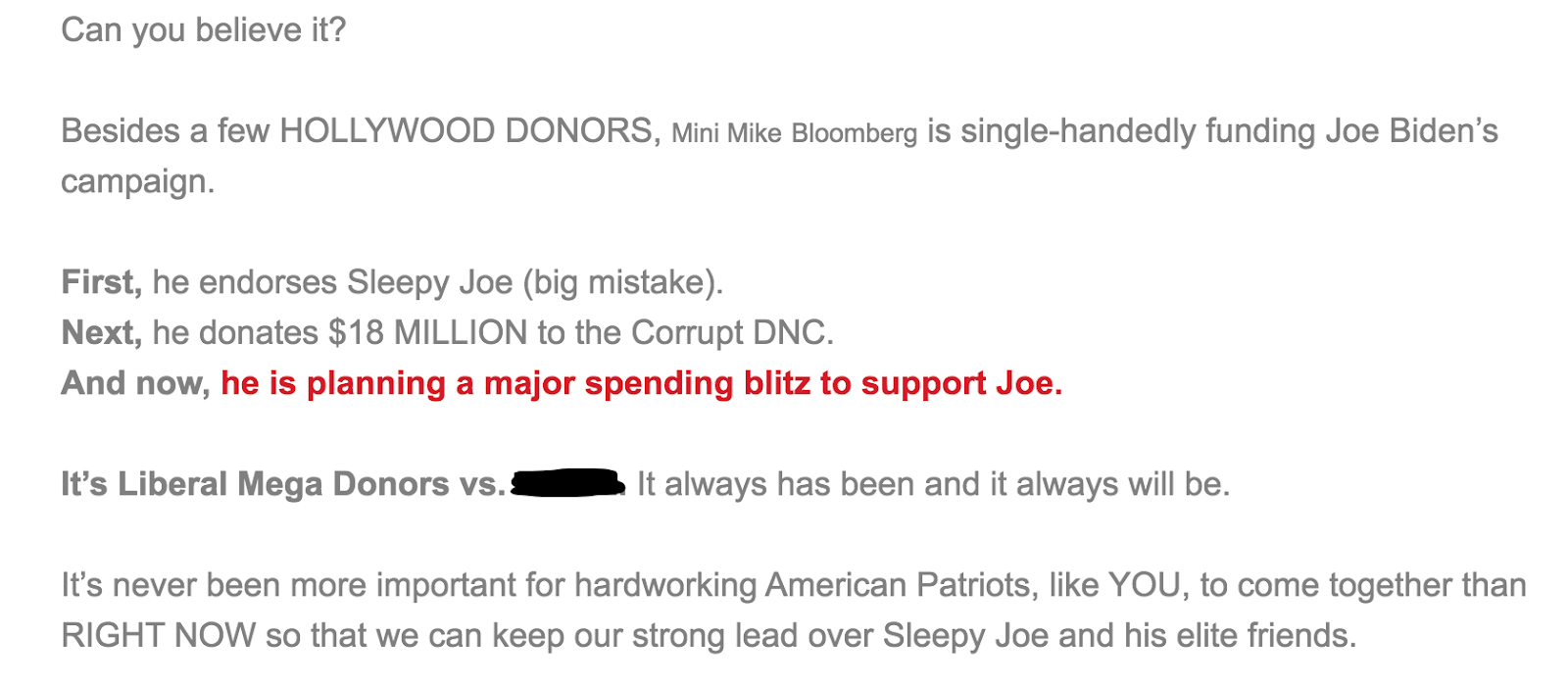

Take, for example, this recent Trump campaign email:

Note the use of caps-lock, colored fonts, and the use of sarcastic nicknames for Mike Bloomberg and Joe Biden.

Contrast that with a recent email from the Biden campaign, employing a more solemn tenor (and monochrome font and no caps lock):

Another Trump email not only makes a product offering—it’s a coloring book depicting Trump as a superhero—but it uses language reminiscent of the heyday of the “as seen on TV” era: “For the first time EVER, we have launched Official Trump Coloring Books. They are already FLYING off the shelves, and we only have 600 left in stock. Since you’re one of President Trump’s top supporters, we’ve reserved one just for you. We can only hold your order for THREE HOURS before we will be forced to release it to someone on our waiting list.”

Yet another—this one using only italics as flourish—reads: “Have you entered to win the beautiful photo that President Trump signed for you? He hand-signed one of his favorite photographs to give to one lucky supporter – someone who has been there for him since the very beginning – and we can’t think of anyone who is more deserving of it than [email recipient].”

Meanwhile, the focus of a second Biden campaign email is on the potential supporter: “This campaign will be about you: the issues you care about and the conversations we’ll have in the months to come.”

And then there are the campaign websites. The contrasts have less to do with design and functionality (although the Biden site does have a train that travels along the track as you scroll vertically, a reference to the fact he rode Amtrak back and forth during his time in the Senate to be with his family as much as possible) than they do, again, with the tone of the content.

Biden’s site focuses heavily on his back story, with details on his family’s many highs and lows. And the site also outlines his policy stances in great detail.

Trump’s website hits you with popup ads asking for contributions before you can even see what’s on the site. And when you get past that, there is an RSS feed to his latest tweets, a listing of the various “coalitions” working to get him elected, and ways to get involved. What passes for a policy presentation is a sub-site that details his “promises kept” including on immigration, regulatory reform, and foreign policy.

There’s another significant difference. Biden does address Trump at various places, mostly to criticize policy choices that he disagrees with, such as expressing dismay that “President Trump uses family separation as a weapon against desperate mothers, fathers, and children seeking safety and a better life” in his discussion of what his immigration policy will be.

Meanwhile, visitors to the Trump website might be invited to watch an ad attacking Biden on China before clicking through to the website, and a video under Trump’s “news” section is titled merely “Another Biden Interview, Another Disaster.”

In Vanity Fair, veteran campaign reporter Peter Hamby concludes that “Biden will lose in November if he chases virality and follower counts that don’t actually grow support among voters, and he’ll lose if he tries to Xerox another candidate’s playbook. … Biden can win if he understands that he doesn’t need to ‘win the internet’ to win the White House.” But Biden isn’t as much ceding the internet as, through his campaign’s digital execution, making a bet that character—or more precisely, being a good guy with a tight family—will be the thing that wins voters.

And being a good guy with a close family is a specific image beyond simply not being Donald Trump. This is an important distinction from the 2016 campaign. Yes,Hillary’s campaign attempted to position her as “not Donald Trump,” but that strategy was undercut by her irrepressible arrogance (see “deplorables”) and the off-again-on-again investigation around her private email server.

In theory, a “good guy with a close family” can withstand the opposition’s attempts to tarnish his reputation, because supporters and crossover would see criticisms of candidate in a different light.

What Trump’s campaign tone shows is that, whatever the RNC’s old guard went through last time in a desperate attempt to preserve some remnants of the party’s traditional approaches to conservatism, that won’t be part of the process this time. Right out of the gate, the party is Trump and Trump is the party. #MAGA isn’t something to be tolerated in the pursuit of power, it’s now officially what the party leads with and fully embraces.

Things are bound to be less binary (read “messier”) as the campaign grinds along, of course. Any good election bingo card will include squares with “Access Hollywood,” “Tara Reade,” “Impeachment,” and “Where’s Hunter?” on it. And these days even approaches to a global pandemic are divided along party lines.

But above all else, as evinced by their digital messaging, the candidates have made likability the dividing line. Joe Biden believes voters want a POTUS they like; Donald J. Trump thinks voters couldn’t care less. The contrast is distinct, but “they go low, we go high” didn’t work for the Democrats in 2016. Will it work this time?

Ward Carroll is a retired naval aviator and novelist. Follow him on Twitter at @wardcarroll.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.