When Trump supporters envision an America made great again, they are likely picturing the 1950s: a decade in which the U.S. military was preeminent in the world, its economy enjoyed a trade surplus, and its population was homogeneous. Yet this mythical vision of the past obscures as much as it reveals. For it was during this decade that the U.S. government made commitments that would lead to futile military interventions, sapping the nation’s martial confidence and economic strength. And it was during these years that a postwar civil rights movement took shape that would desegregate the South and decouple the reflexive equation of American whiteness with American citizenship.

It was squarely within the mythical 1950s that the U.S. government launched the most public effort to deport large numbers of undocumented Mexican migrants: Operation Wetback. And it’s this example that many on the Trump team are citing as they seek to implement a mass deportation program. But why this campaign from 1954, when there are more recent attempts to draw experience from?

The reasons all fit into a mythical reading of the 1950s. Operation Wetback was big, bold, and public. It was effective. And it was quick. Yet, leavening myth with reality, we can now conclude its approach was short-sighted, its conduct was brutish, and its long term results were fleeting. Operation Wetback was futile. It is a cautionary tale in trusting the political platitudes and simplistic prescriptions that promise a rapid solution to the immigration crisis.

The number of undocumented border crossings, as indicated by the U.S. Border Patrol’s (BP) apprehension of Mexican migrants, was rising in the years before Operation Wetback: 458,215 in 1950, 500,628 in 1951, 534,538 in 1952, and 875, 318 in 1953. BP agents had been using various methods to stem the tide, notably fences and cross-border raids. So when President Dwight Eisenhower appointed an old classmate from West Point, Gen. Joseph Swing, as the new commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) in May 1954, many hoped border enforcement would be instilled with a degree of military efficiency. Swing was soon promising a swift conclusion to the “wetback problem.” An economic recession, which nearly doubled the U.S. unemployment rate between 1953 and 1954, put the issue of undocumented Mexican labor migration into sharp focus for Americans.

A stage was being set. The INS worked hard during the first months of 1954 to ensure American agricultural growers had a plentiful supply of documented Mexican workers. Advance public announcements of Border Patrol roundups convinced many undocumented migrants and their families to voluntarily leave the United States. The U.S. Department of State informed Mexico’s government to prepare for a sudden and large influx of its nationals. Then in mid-June 1954, “Operation Wetback” began.

Border Patrol agents built roadblocks along routes that led to and from the border, including around Nogales, Arizona and El Paso, Texas; teams of 12 BP agents roved in jeeps, planes, and trucks throughout California, Arizona, Texas, and other parts of the country, searching for Mexicans. Public spaces such as parks, fields, and country roads were converted into temporary detention facilities as apprehended Mexican nationals, mostly men, were processed for deportation (the deportation of women and children was kept minimal because it was considered a bad look for the Border Patrol). Migrant camps, ranches, farms, restaurants, and hotels were raided for migrant workers. Journalists followed BP agents everywhere they went, photographing and documenting the apprehensions.

The INS claimed that well over 1 million immigrants exited the United States during the latter half of 1954. Nearly 27,000 were formally deported, yet the great majority of departures were voluntary. There were accounts of harsh and abusive treatment of Mexican immigrants by BP agents. Some Mexican migrants were reportedly “dumped” just across the border—sometimes in the middle of the desert—with no plans for their provision. Migrants were often packed into cargo vessels and shipped from Texas to Mexico ports. In one case, migrants on a ship sailing from Port Isabel, Texas, to Veracruz, Mexico, were subjected to conditions that resembled an “eighteenth century slave ship.” But the goal of Operation Wetback had been met: a militarily precise removal of foreign laborers who were stealing work from American citizens and undermining the stability of the United States. By March 1955, Swing crowed that the undocumented Mexican migration problem was resolved.

Of course, there is a precedent for everything in history. The precedent for Operation Wetback was the Repatriation crisis of the early 1930s, when an estimated 300,000 Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans went back to Mexico. A sudden lack of work precipitated by the Great Depression, along with public prejudice, combined to drive them out of the country. Even though most repatriados left the United States voluntarily, their departure was coerced. News of harassment, rumors of local authorities visiting Mexicans’ homes to request immigration documentation, and the general mood of persecution convinced many Mexicans to return south. Voluntary departure did not classify undocumented migrants as deportees, allowing them to apply for legal readmission to the United States once they were on the other side of the border. Local governments and railroad companies facilitated Mexicans’ return southward by discounting transportation costs. Even local charities played a part in pressuring Mexicans to leave the United States by withholding services.

Cities throughout the United States organized campaigns to drive out Mexican workers from their communities, but Los Angeles County was considered the “hotbed” of repatriation—over 12,000 Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans would depart that county alone by the mid-1930s. Immigration agents and local police carried out a string of well-publicized raids, detaining and questioning thousands of persons suspected of being in the country illegally. Count officials opined that the departure of immigrants would fix rising unemployment and crime problems. The local police chief, Roy Steckel, developed a novel, 20th-century type of public inquisition called “scareheading,” which involved having several federal officials preside over a few arrests, ensuring that those arrests received ample publicity. Such practices created a social environment so hostile to immigrants that many left the United States willingly; indeed, historians Francisco Balderrama and Raymond Rodríguez argue that Mexicans “elected to face deprivation in their homeland rather than endure the disparagement heaped upon them in El Norte. ... In Mexico they might suffer hunger pains, but at least they would be treated like human beings.”

Voluntary departures suited U.S. immigration authorities just fine. Deportation proceedings—which required court hearing and background checks—were cumbersome and time-consuming processes that federal and state governments preferred not to undertake. Due process gummed up the works of mass deportation. Instead, social coercion was the ticket. By making living conditions for immigrants in the United States so intolerable, and dialing up a climate of fear to such a fever pitch, the undocumented would have no choice but to leave. Problem solved.

Both the Repatriation crisis and Operation Wetback were spurred by economic recessions, but they were underpinned by a palpable American prejudice toward immigrants. The language of exclusion was more blatant in the early 1930s. Anti-immigrant congressmen like Rep. John Box said Mexicans did “not make good citizens” and that they were “dirty and diseased.” Twenty years later, the language was nearly as direct, such as when Commissioner Swing stated that undocumented Mexican migrants constituted “an actual invasion of the United States,” and that the deportation program’s objective was a “direct attack… upon the hordes of aliens facing us across the border.” The name itself, Operation “Wetback,” indicates the public nature of prejudice in mid-20th century America.

Another chief characteristic shared between government deportation projects of the early 1930s and mid-1950s was the coordination of federal, state, and local authorities. It is hard to imagine such robust cooperation these days, but ironically, the channels for cooperation between local, state, and federal governments to deport immigrants have only increased in recent decades. The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA) made it harder for undocumented immigrants to adjust their status to that of a legal immigrant while simultaneously making it much easier for these undocumented immigrants—including minors and children—to be apprehended and deported. Under section 287(g) of the new law, local and state police could be trained to enforce federal immigration law, more offenses were deemed deportable, it was easier to deport criminals (“expedited removal”), and deportation decisions were made by immigration courts with stricter judicial review procedures. The IIRIRA stipulated that 28 distinct offenses including “crimes of violence” that carried a prison sentence of a year or more could result in deportation. Perhaps most dramatically, the law also instituted retroactive punishment, in which pre-1996 crimes that were formerly not defined as aggravated felonies—such as traffic violations—were now classified as such, providing the government grounds for deportation. Convicted residents could be deported even if they had completed their prison sentences.

Not coincidentally, deportations of undocumented immigrants shot up. For most of the twentieth century up to 1990, deportations averaged about 20,000 per year. Between 1990 and 1995 they increased to 40,000 per year. During the late 1990s, after passage of the IIRIRA, deportations rose to nearly 200,000 per year. Additionally, new regulations from 2002 to 2006 allowed immigration officials to expeditiously return undocumented migrants found within 100 miles of the border up to 14 days after their actual crossing. These new measures included authorization to build a border barrier and to create the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency (ICE), which is spearheading the current deportation campaign.

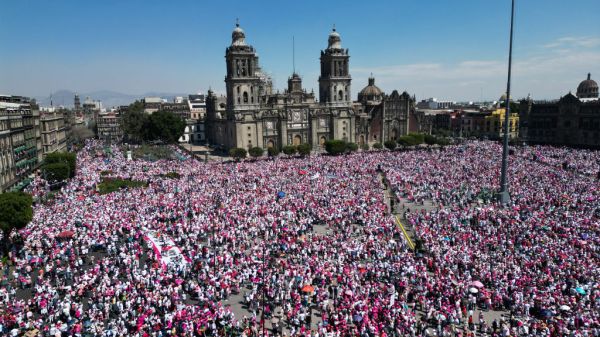

The federal government’s ability to deport immigrants has grown in Operation Wetback’s long wake, even if public toleration for anything resembling what happened in the summer of 1954 is ambivalent. Some Americans undoubtedly want to support Trump’s desire to deport millions of immigrants. Private security firms and even private citizens may soon directly participate in such efforts. And the state of Texas has offered the Trump administration the use of 1,400 acres to host deportation facilities and to build a border wall. Other Americans decry such policies, protesting what they see as an unethical and unconstitutional approach to immigration control and a federal government’s blatant attempt at legal overreach. Many Democratic-leaning city and state governments offer themselves as sanctuaries to immigrants and spurn federal officials’ demands that local authorities cooperate in mass deportation. Such responses to U.S. immigration policy taps into the historical example of the Sanctuary movement, which began in the early 1980s to safeguard Central American refugees who were denied asylum by the U.S. government.

Americans’ disagreements over immigration cut along political, legal, economic, and even philosophical lines. A fundamental question raised by the immigration debate is who belongs in a nation-state. What makes an individual a legally-protected entity, their personhood (regardless of the nation-state) or their citizenship (because of the nation-state)? Another relevant legal question to immigration is this: are “illegal” aliens accorded due process because of their personhood or are they denied it because they are not citizens of the United States? The 14th Amendment—the same Constitutional statute of 1868 that created the notion of birthright citizenship (and that has been targeted recently by the Trump administration for cancellation)—also granted due process protections to all “persons” regardless of their citizenship status. Seen in this light, are operations like mass deportation a violation of undocumented immigrants’ civil protections? The American public, its leaders and courts have debated the topic for well over a century.

The historical legacy of Operation Wetback is a flash in the pan: a momentary, shocking flame burst that quickly dissipates. It got attention and immediate results. Yet it failed to provide a lasting solution to the immigration issue. American policymakers did not consider what would happen to all the migrants deported. It was assumed that once migrants had been expelled, they would cease being a headache for U.S. leaders. That assumption was wrong. A new border crisis was proclaimed by the mid-1960s as rates of undocumented migration grew. By the early 1970s, American media broadcast panic at rising migration. One Arizona newspaper headline from March 1973 read, “Illegal Aliens Flooding Yuma, California Area.” Undocumented migration would continue to rise through the last years of the twentieth century, especially after the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect in 1994. For critics of immigration, free trade had an unfortunate tendency of creating the conditions for the free movement of people.

Ultimately, Operation Wetback failed because it treated immigrants as numbers instead of people. The Trump administration is taking a similarly mistaken and ahistorical approach to the immigration problem. Present-day advocates of mass deportation would do well to consider the various factors in migrant-sending countries that lead people to the United States: crime, drug wars, weak government institutions, depressed economies. Of course, the United States is not isolated from these international factors. Indeed, in many ways the United States contributes to the problem with its proliferation of guns and consumption of illicit substances. Immigration, then, is a transnational concern that cannot be solved through domestic mass deportation programs. Instead, to find a lasting solution to the problem, policymakers must analyze and empathize with the reasons individuals make the fateful decision to leave their home country for a distant destination. And then they must legislate and negotiate accordingly.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.