The Last Hurrah was a very fine movie, made by John Ford in 1958 and starring Spencer Tracy. It is based on an even finer book by Edwin O’Connor, which had been a boffo bestseller two years prior.

They tell the story of Frank Skeffington, the mayor of a never-named big city in the Northeast. O’Connor keenly, wistfully tells the story of how an old campaigner, already an astonishing 72 years of age, makes one last stand against the encroachments of televised, college-educated, professionalized politics.

Skeffington is unmistakably based on Boston political boss James Curley, who lost his bid for a fifth term as mayor in 1949. Omitted, of course, is the part about how Curley spent part of his fourth term in prison for yet another episode of brazen corruption. Or how a deeply indebted Curley had returned to City Hall for that term after leaving a seat in Congress, probably at the urging and compensation of Joe Kennedy, who wanted the spot for his war-hero son, Jack.* Or how Curley had won the House seat in the first place by smearing his opponent as a communist sympathizer.

Curley was a culture war populist who derived his power from a combination of public works projects, brutal corruption, and by delighting working-class Boston with theatrical affronts to the already-toppled WASP establishment.

Here’s the Harvard Crimson recounting the arrival of then-Massachusetts Gov. Curley at the college’s 300th commencement in 1936:

“Consistent in minute detail to the precedent of the colonial governors (which had not been observed since Harvard’s Centennial), Curley heralded his arrival with a massed band, an escort of fully-armed lancers, the National Guard, trumpet sounds, bugle calls, the beating of drums, the shooting of guns, and the cheers of a mixed collection of Boston Irish such as Harvard Yard had never imagined.”

The story of The Last Hurrah is about how slick, televised, modern politics defeated the earthy, intimate, old-school style. True enough. But the era was the last gasp of something else, too: The reliability of Irish Americans as a nearly monolithic bloc of support for the Democratic Party.

The election of Jack Kennedy as president in 1960 was a coda to a century of a mostly prosperous marriage between Irish Americans and the Democratic Party—a triumph before the coming divorce. “There’s no point in being Irish if you don’t know the world is going to break your heart eventually,” future Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, whom Kennedy had appointed to a post in the Department of Labor, said in an interview after the president’s assassination in November 1963. “I guess we thought we had a little more time.’’

But it’s not as if the Irish vanished from politics. Every president since Kennedy, except for Donald Trump, has been able to boast of his ancestral connections to Ireland, even Barack Obama. Being Irish is a good thing in a country where 31.5 million Americans claim Irish ancestry. It’s just that it doesn’t have any particular salience when it comes to partisanship. Now, knowing only that a voter is of Irish extraction is of no more use in guessing their vote than would be their shoe size. Ask Kevin McCarthy or Mitch McConnell.

The story of the journey from The Last Hurrah to today could be told in many different ways. We could focus on the weakening power of machine politics, as the book did. We could talk about the changes in the parties’ coalitions, in which African American voters came into the Democratic fold, while working-class whites migrated to the Republicans.

But the most important part is that being Irish became a less meaningful distinction for the Irish themselves and the world they lived in.

Boston’s current mayor is, of course, a Democrat. And like Curley, is a child of immigrants. But Michelle Wu’s parents came from Taiwan, not County Galway. The Irish, once the downtrodden slum dwellers whom Curley championed, have long since moved up and moved out. Boston may not have an Irish mayor anymore, but the town manager in Brookline? You can bet your shillelagh.

As Americans got over their bigotry toward the Irish, particularly of the Roman Catholic kind, being Irish became just another trait to be proud of, not something that would make one need to set his jaw against the world. And as Irish Americans spread out across the country and up the ladder of achievement, they came to resemble the other people of every background with whom they shared their lives. It was a distinction, not a difference.

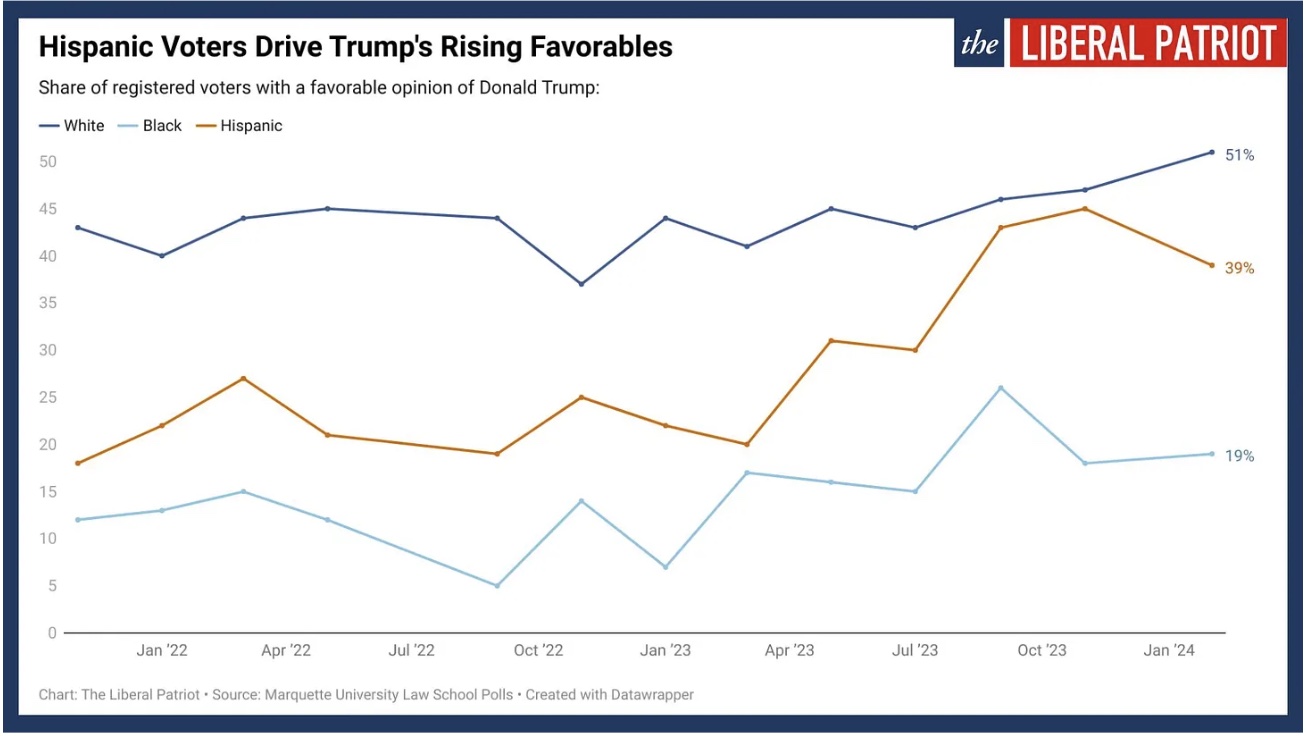

This week, the political class has been agog over some charts from data wiz John Burn-Murdoch of the Financial Times, with one image drawing 6.4 million views online. Burn-Murdoch is telling a familiar story about President Joe Biden’s struggles with ethnic minorities, one we explored in detail here last month. But his charts still look shocking, showing the non-white vote for Republican presidential candidate heading to 50 percent this year from the low single digits in 1964.

But, a couple of things to please bear in mind:

First, Burn-Murdoch is mashing up election results with polls to create the stunning image. It is certainly true that the polls from early this election year point to serious setbacks for the incumbent with ethnic minority voters, particularly Hispanic Americans. But putting poll results on the same plotline as election results is a little hinky. And in March? Ehhhhhh …

Second, being “non-white” isn’t nearly as meaningful as this treatment suggests.

America is not an apartheid state, nor a white supremacist one. Whiteness is a subjective idea, almost entirely determined by the individual. Is a person with one Hispanic grandparent white? It depends on how he or she answers the census question. Are Arab Americans white? Depends on whom you ask.

Lumping together every person not of wholly European ancestry into one group is not particularly edifying. To suggest that the descendants of African slaves and Asian immigrants of the past 40 years are part of the same voting bloc not only flattens differences worth examining but also suggests a political solidarity that doesn’t exist.

As we discussed last month, Biden has real problems with younger black voters. For the generations born after the struggle for civil rights, the old attachments to the Democratic Party are fading. Surveys show a small shift to the GOP among younger black voters, but in a constituency that has been almost wholly Democratic for 60 years, even a few points could be deadly. A 4-point swing with black voters could doom the blue team in Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan, North Carolina, and Wisconsin.

Some of the shift with black voters is also a reflection of more recent history, too. It was not uncommon for Republican nominees for decades to get double-digit black support. Then came Obama, who, not surprisingly, did better. Then came Trump, who after crashing and burning in 2016 with black voters, seems to be doing much more like his Republican predecessors.

The Democrats’ problem with Hispanic voters is even more pronounced. As Nate Silver lays out here, the shift is real and ongoing. But this is itself an old story, indeed the same one we heard about Mayor Skeffington and The Last Hurrah. A generation ago, being Hispanic in America made someone different. Increasingly, it makes one distinct. Rather than being set apart, one adds their own character to the whole.

Research shows clearly that being Hispanic in 2024 America means something very different than it did even at the start of this century. Like the children and grandchildren of Irish immigrants 60 years ago, Hispanic Americans are less of a set-apart class and more a part of the enduring national character. If your last name is Gonzales, that will tend to matter much less in how you vote than how much you earn, whether you have a college degree, where you live, whether you are religiously observant, old or young, etc.

That goes double for the growing number of Americans of Asian and South Asian ancestry or origin. While certainly history tells us of horrible abuses of Asian Americans in the past, their story is mostly a newer one, and one very different from the multi-generational horrors of slavery and Jim Crow. Being black in America is not the same as being non-white. It remains, sadly, a difference rather than a distinction. But for Asian Americans, the story of success and achievement is so well known that much of the debate now centers around reverse discrimination.

None of this is to say that Democrats don’t have real problems this year, with lots of different voting blocs. This is only a reminder that the marvelous engine of assimilation is still turning differences into distinctions.

One day, perhaps when America elects its first Hispanic or Asian president, we will say it was the last hurrah for using terms like “non-white” for any kind of meaningful analysis.

Holy croakano! We welcome your feedback, so please email us with your tips, corrections, reactions, amplifications, etc. at STIREWALTISMS@THEDISPATCH.COM. If you’d like to be considered for publication, please include your real name and hometown. If you don’t want your comments to be made public, please specify.

STATSHOT

Biden Job Performance

Average approval: 38.8%

Average disapproval: 57.6%

Net score: -18.8 points

Change from one week ago: ↑ 0.8 points

Change from one month ago: ↓ 2.0 points

[Average includes: USA Today/Suffolk: 41% approve-55% disapprove; New York Times/Siena: 38% approve-59% disapprove; Reuters/Ipsos: 37% approve-58%; Quinnipiac: 40% approve-57% disapprove; Gallup: 38% approve-59% disapprove]

Polling Roulette

TIME OUT: NO BLARNEY

History: “Most of those who wear green [on St. Patrick’s Day] probably don’t realize that the color has only a tenuous connection to St. Patrick, and actually originated as a symbol of rebellious Irish nationalism. … ‘The earliest depictions of St. Patrick show him clothed in blue garments,’ Elizabeth Stack says. … But during the centuries that Ireland was ruled by the English, the color blue fell into disfavor among the Irish. Henry VIII … gave Ireland a coat of arms that depicted a golden harp on a blue background. … … In the Great Irish Rebellion of 1641, Irish military leader Owen Roe O’Neill’s sailing vessels flew a flag that depicted an Irish harp on a field of green instead of blue. … Even after that uprising was crushed, Thomas Dineley, an Englishman who traveled through Ireland in 1681, ‘reported people wearing crosses of green ribbon in their hats on Saint Patrick’s Day.’ … As Irish immigrants arrived in the United States and other countries in the 1800s, they took the custom of wearing green with them.”

BIDEN, TRUMP BOTH STRUGGLE TO REBUILD WINNING COALITION

Associated Press: “The Democratic coalition that sent Biden to the White House came in with high hopes about his presidency — which may have been a double-edged sword. … Only about half of Black adults have approved of Biden’s job performance in recent months, down from 94% in early 2021 — a huge decline in satisfaction among a cornerstone of the Democratic coalition. … Biden’s approval rating has also fallen at least 20 percentage points among Hispanic adults, independents, young adults and moderates. … There are serious risks for Trump if he can’t broaden his appeal beyond his Republican base this time around. He lost moderates to Biden in 2020, and the first head-to-head Republican contests showed continued signs of trouble for Trump among these voters. … Roughly 6 in 10 moderate Republicans in New Hampshire and South Carolina were concerned that Trump is too extreme to win a general election.”

Harris visits abortion clinic as Dems double down: New York Times: “Vice President Kamala Harris plans to meet with abortion providers and staff members on Thursday in the Twin Cities, a visit that is believed to be the first stop by a president or vice president to an abortion clinic. … The mere sight of a top Democratic official walking into an abortion clinic will offer the clearest illustration yet of how the politics of abortion rights have shifted for the party — and the nation. … President Biden’s campaign is leaning into abortion, running ads featuring the testimonials of women denied access to the procedure in conservative states…”

After Trump takeover, RNC ditches minority outreach program: New York Times: “The Republican National Committee, days after electing new leadership and overhauling its presidential campaign operation, is shuttering all of the community centers it established for minority outreach nationwide and laying off their staffs. … The community centers, which were based in several states including California, New York, North Carolina and Texas, were part of a yearslong effort to encourage Black, Latino, Asian and Native American voters to join the party. … The centers often hosted political rallies, dances and potlucks, and some even helped community members prepare for the U.S. citizenship test.”

GOP FRETS ABOUT RFK JR.’S ANTI-VAXXER PULL

Washington Post: “Donald Trump set off a panic in some of the more extreme corners of his base last week during President Biden’s State of the Union. Trump’s offense? Taking credit for the coronavirus vaccines that Biden hailed. … The reason for that supposed peril is the independent candidacy of perhaps the country’s most prominent vaccine critic, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. … Could Trump’s role in forging the coronavirus vaccines — and his frequent praise for them — send portions of his party’s growing anti-vaccine contingent into Kennedy’s camp? … The main question is how many Republicans feel strongly enough about this issue. … Despite his role in pushing for the vaccines, and however much he’s praised the vaccines, it doesn’t seem to have cost him — at least, to the extent people have actually processed all of that. … But Kennedy presents a more direct contrast, and he seems to be leaning in on this issue a bit more now.”

As he teases Aaron Rodgers, Jesse Ventura for VP pick: New York Times: “Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has recently approached the N.F.L. quarterback Aaron Rodgers and the former Minnesota governor and professional wrestler Jesse Ventura about serving as his running mate on an independent presidential ticket, and both have welcomed the overtures. … Mr. Kennedy confirmed on Tuesday that the two men were at the top of his list. … Mr. Kennedy said that he had been speaking with Mr. Rodgers ‘pretty continuously’ for the past month. … The involvement of Mr. Rodgers — who is expected to start for the New York Jets this fall, at the height of campaign season — or of Mr. Ventura could add star power and independent zeal to Mr. Kennedy’s outsider bid.”

NO LABELS ANNOUNCES NOMINATING COMMITTEE

Washington Post: “The centrist group No Labels announced a committee of 12 people Thursday who will decide in the coming weeks who should appear on the group’s potential third-party presidential ticket. Led by co-chairs of the group — including former senator Joseph Lieberman (I-Conn.), retired Navy Adm. Dennis Blair and civil rights activist Benjamin F. Chavis Jr. — the committee will then take its recommendation to a separate group of No Labels supporters that is prepared to formally nominate the ticket on 48 hours’ notice. … The announcement comes a day after the resignation of another co-chair of the group, former North Carolina governor Pat McCrory. … It also comes days after No Labels started serious conversations with former Georgia lieutenant governor Geoff Duncan. … Lieberman said in an interview on Wednesday that the group would have the ability to stop a candidacy from moving forward after a few months if it failed to gain traction.”

While Dems wage war on third parties: NBC News: “The Democratic National Committee is building its first team to counter third-party and independent presidential candidates as the party and its allies prepare for a potential all-out war on candidates they view as spoilers. … The DNC has hired veteran Democratic operative Lis Smith … to help oversee an aggressive communications component of its strategy, which also includes opposition research and legal challenges. … The move comes as a coalition of outside groups — which includes Democratic and anti-Trump Republican organizations — stockpile money and work to stymie third parties. … Democrats have long blamed Green Party candidates such as Jill Stein and Ralph Nader for contributing to their losses in 2016 and 2000.”

MENENDEZ HINTS AT INDY BID AS LEGAL TROUBLES GROW

NBC News: “Indicted Sen. Bob Menendez, D-N.J., is considering running for re-election in November as an independent. … Menendez, who along with his wife, Nadine Menendez, is facing 18 federal counts and is charged with taking bribes … is now making calls to allies about his record and career and is preparing to collect petitions to run in November as an independent. … A clearly frustrated Menendez did not deny that he’s planning to run as an independent when asked by NBC News Thursday afternoon, saying multiple times: ‘I don’t have to declare what I am doing. When I do, everybody will know.’”

County lines pivotal to Murphy’s edge: New York Times: “[Tammy Murphy’s] audacious play for a highly coveted seat has prompted critics to pan her candidacy as rank nepotism. She is up against Andy Kim, a popular three-term Democratic congressman from South Jersey. … Kim has filed a federal lawsuit challenging the way that the ballots are designed in primary elections in most of the state’s 21 counties. … The system is known in New Jersey as “the line,” and it enables Democratic and Republican county leaders to bracket their preferred candidates for every office in a single column or row on the ballot. Unendorsed challengers appear off to the side or along the ballot’s edge. … The line is also how county leaders maintain their power and their access to government contracts and jobs that are often seen as the spoils of political victory.”

DEMS—AND TRUMP—BOOST MORENO

Axios: “Former President Trump and meddling Democrats are both scrambling to get their preferred Republican candidate — businessman Bernie Moreno — over the finish line in Tuesday’s Senate GOP primary in Ohio. … Democrats view Moreno as the weakest general election opponent for vulnerable Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio). … Trump will rally with Moreno in a ‘surprise’ visit near Dayton, Ohio, on Saturday, three days before the March 19 primary. … A late splash of spending from outside groups shows how high the stakes are for Republicans — and for Democrats anxious to defend their slim Senate majority. Duty and Country PAC, a group tied to Senate Democrats, is spending $2.5 million on a TV ad highlighting Moreno’s ties to Trump — seeking to boost him with the GOP’s conservative base.”

Feeling the Bern? Moreno under fire for adult website profile: AP: “After vaulting into the top tier of contenders with a coveted endorsement from Donald Trump, Moreno — who has shifted from a public supporter of LGBTQ rights to a hardline opponent — is confronting questions about the existence of a 2008 profile seeking ‘Men for 1-on-1 sex’ on a casual sexual encounters website called Adult Friend Finder. … Questions about the profile have circulated in GOP circles for the past month. … On Thursday evening, two days after the AP first asked Moreno’s campaign about the account, the candidate’s lawyer said a former intern created the account as a prank. The lawyer provided a statement from the intern, Dan Ricci, who said he created the account as ‘part of a juvenile prank.’ … Moreno’s potential vulnerability has sparked frustration among senior Republican operatives and elected officials in Washington and Ohio.”

BRIEFLY

Colorado Republican Rep. Ken Buck retires early, Boebert to miss out on special election—Denver Post

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul tries to dodge down-ballot disaster—Politico

Vice presidential prospect Kristi Noem sued after posting bizarre dentistry promotion—The Guardian

WITHIN EARSHOT: HEY, LADIES

“Ok, Katie, look. To be candid, Scarlet Johansson is hot.”—Sen. Ted Cruz chats with Sen. Katie Britt about Scar Jo’s spoof of Britt’s State of the Union response.

And

“I just hope you didn’t find any risque pictures of my wife in a bathing suit. Which you probably did. She’s beautiful.”—President Joe Biden jokes with prosecutors about the FBI’s thorough investigation of his home.

MAILBAG

“Isn’t there still a reasonable chance that Donald Trump’s trials still could derail his run for president? Do you think the price tag alone of the criminal and civil cases might limit his campaign resources and create some doubts in the MAGA crowd about his self-promotion as a business icon? Long gone are the early days when he claimed to be so rich that he didn’t need outside financial support to run for office. He can’t even pay his legal bills without outside donors.”—John Dixon, Charlotte, North Carolina

Mr. Dixon,

That very much depends on whether any of those trials actually take place before the election. It seems increasingly unlikely that will happen.

But certainly the criminal charges against Trump have had, and will continue to have, significant effects on his candidacy. To date, the effects have been, on the whole, favorable to his chances by working to unify Republicans behind him against the Biden administration and Democratic prosecutors at the local level.

At the same time, the charges have helped disquiet some Republican voters and, no doubt, worked against Trump with many independents.

What we will see, though, is if the Biden campaign can effectively advance what could be a dangerous argument to Trump: that he would use a return to power to escape punishment for the crimes with which he is charged. And a related one: that the individuals who have and will fund Trump’s legal defense have put Trump in their pockets.

How the legal proceedings play out before the election could indeed fuel suspicions, but probably not more than Trump will himself.

All best,

c

“Katie Britt’s introduction reminds of Sarah Palin, looking like she has no business being a serious national candidate. Since her kitchen talk was pre-recorded, how come no one said ‘Whoa, we’d better do take two?’ Seems like her handlers let her down. How do these rebuttals work? Was she filmed that day? Would she have had a couple days to get it right? A real party should never have let that go out.”—Michael Johnson, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Mr. Johnson,

There’s no doubt that Sen. Britt was done a grievous disservice by her handlers, but it’s not true that the rebuttals are pre-recorded.

The major television networks work cooperatively in what we call a “pool,” in which the outlets take turns providing coverage for major, scheduled events. For the State of the Union address, one network helms the production of the main speech, another takes the other party’s official response. The person who gives the response is chosen long in advance by the congressional leaders of the opposing party. The designated producers then make arrangements to be in place at a location of the respondent’s choosing, in this case, a kitchen in Alabama. The live feed of both speeches is then made available to all the networks.

Katie Britt is no Sarah Palin. Whatever you think about the senator’s policies, she’s a smart, capable lawmaker who has won the admiration of many in Congress, including some Democrats.

What pretty obviously happened was that Britt had been overcoached in rehearsing her speech. She may have given it live, but it was written long in advance of ever hearing what President Joe Biden had to say. Britt was no doubt encouraged to emote, emote, emote—really wring every possible drop of pathos out of the moment. And when the lights came up and Britt knew that tens of millions of Americans were watching live, she played it for all she was worth.

Her over-the-top performance was indeed an embarrassment, but she is not a weirdo. She does have a tendency to speak in breathless tones, but not in the exaggerated mode of her speech. Neither did it help that her team placed her in a dimly lit, haunted-looking kitchen.

These rebuttals are usually misadventures, but the parties don’t want to pass up the chance to speak to the largest audience of each year for a political event. But the partisan leaders themselves are generally not telegenic or appealing spokespeople. Plus, the speaker of the House is stuck on the rostrum.

I suspect the State of the Union rebuttal will claim more victims in years to come until—Lord, hear our prayer—the whole show is abandoned in favor of something more modest and less spectacular.

All best,

c

“Regarding Nate Moore’s takeaway from the California Senate race, the [Adam Schiff-Steve Garvey] match up benefits the national Democratic Party money machine and disadvantages the national Republican Party’s campaign coffers. I believe Nate misses the bigger takeaway: chiefly that California’s 30-year experiment in election engineering (meddling) finally succeeded in delivering two moderating candidates. Although ironically that was due in part to Schiff’s campaign using the now ubiquitous Democratic tactic of assisting your lesser perceived general election opponent across the primary election finish line. Schiff is not a Blue Dog Democrat but neither is he a barking mad progressive. In our current political environment of being forced to sit out elections or vote for the lesser of (sometimes very lesser) of two evils I welcome an opportunity to vote in a clearly definable general election even if the outcome is a foregone conclusion in deep blue California. I welcome your thoughts.”—Dan Burch, Turlock, California

Mr. Burch,

I wouldn’t say Brother Moore missed that at all. Nate chose to write about something different: the implications of the Super Tuesday elections on the November vote. And in that task I believe he excelled. One of the great joys of being a writer is when one gets to choose his or her own topics.

But as to your main point, I tend to agree. While we tend to focus on the part Schiff played in propping up Garvey’s campaign, the fact is that more than 6 million Californians voted for Donald Trump in 2020. Schiff wasn’t persuading Republicans to vote for Garvey over another candidate, the Democrat was helping to mobilize them.

Now, in the general election, Schiff will undoubtedly tack to the center of California politics, which is pretty far left of the nation as a whole. But Schiff will not have to maneuver much at all. With a 30-point updraft for Democrats at the top of the ticket in the much-larger general electorate, Schiff could go on a six-month vacation and still strike out Garvey.

Imagine if, instead, Schiff was facing sore loser Katie Porter. Porter’s boundless ambition would no doubt have led her to scorched earth attacks on Schiff. And given the lopsided makeup of the general electorate, they would have been strong disincentives to trying any appeals to Republican voters.

There are lots of ideas banging around in the states about how to fix the badly broken methods by which the parties choose their nominees. But certainly “top-two” all-party primaries like California’s show promise.

All best,

c

You should email us! Write to STIREWALTISMS@THEDISPATCH.COM with your tips, kudos, criticisms, insights, rediscovered words, wonderful names, recipes, and, always, good jokes. Please include your real name—at least first and last—and hometown. Make sure to let me know in the email if you want to keep your submission private. My colleague, the vernal Nate Moore, and I will look for your emails and then share the most interesting ones and my responses here. Clickety clack!

CUTLINE CONTEST: A FACE IN THE CROWD

If there was a hall of fame for the Cutline Contest, this week’s winning entrant would surely be its first honoree. Not only is she quick with her entries, but has a light touch and works well within the comedic construct of newspaper-style cutline writing.

“Former President Trump invites supporters to photograph his other good, some would say perfect, side.”—Linda McKee, Dubois, Pennsylvania

Winner, Derelicte Division:

“I call this one Orange Steel.”—Derek Lyttle, Chicago, Illinois

Winner, Maple Menace Division:

“Vermont?! We need a complete and total ban on Vermont until we can figure out what the hell is going on!”—Tripp Whitbeck, Arlington, Virginia

Winner, Sy Sperling Division:

“Remind Brandon at inauguration, toupee beats plugs. Every time.”—Zach Jones, Piedmont, California

Winner, ‘Woof’ Division:

“Chris was right; 241 days IS a long time..”—Daniel Summers, Knoxville, Tennessee

CUP CHECK

New York Post: “MLB’s new uniforms haven’t exactly been getting rave reviews, and now, the bottom half of the fits are in the spotlight for less-than-sterling reasons. The new Nike-designed and Fanatics-produced uniforms were billed as having lighter materials for the players on the field, but the pants — especially ones that are white — have a see-through quality to them, and that was evidenced in a picture of Giants infielder Casey Schmitt, which went viral for what one could see in the groin region. Schmitt was sitting with a bat for a standard photo day picture, but what baseball fans immediately noticed was the tight and transparent aspects below the waist. … Along with the pants, the tops players have worn have already been called out by one unnamed Orioles player, who told the Baltimore Banner it feels like a ‘knockoff jersey from T.J. Maxx.’ … MLB has defended the new uniforms, calling them ‘world-class.’”

*Correction, March 16: This piece initially misspelled Joe Kennedy’s surname.

Nate Moore contributed to this report.