The problem with taking House Republicans’ new impeachment inquiry seriously is that it requires taking House Republicans seriously.

That’s hard. And not just for those of us who’ve grown hostile toward the party.

I was chatting a few days ago with relatives who watch Fox News avidly and was surprised when one commented that Kevin McCarthy’s conference … doesn’t seem to do much. In fairness, there’s not much the conference can do legislatively while government is divided. But even by those low expectations, even to loyal viewers of a GOP propaganda outlet, it’s begun to sink in that the new House majority appears less than deadly serious about formulating workable policy.

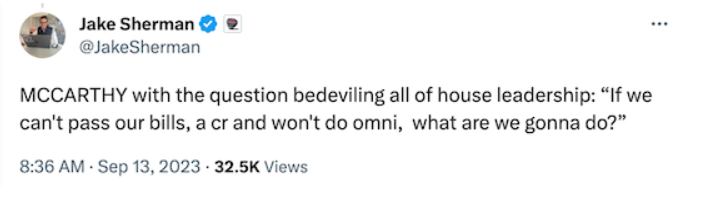

I thought of that on Wednesday morning as news trickled out of the speaker’s meeting with his members about the impending government shutdown.

In other words, if Republicans can’t agree on individual spending bills, can’t agree on a comprehensive spending bill, and can’t agree to fund the government short-term while they work through their disagreements, er, what then?

Why, an impeachment inquiry, of course.

Suspicion of McCarthy’s motives in launching an inquiry at this particular moment is bipartisan. Democratic Rep. Jamie Raskin speculated that the speaker was forced to choose by the MAGA wing of his caucus between “a ridiculous government shutdown or a farcical impeachment exercise.” One unidentified Senate Republican agreed about the timing, sneering, “Maybe this is just Kevin giving people their binkie to get through the shutdown.” The speaker knows he’ll eventually have to cut a deal with Democrats on government funding—thereby enraging fiscal conservatives and Trumpy populists—so, in order to keep his job, he needs some way to appease the right-wing base.

The surest way to do that is to confront the left, and there’s no confrontation quite so grand as moving to impeach the president. Remember, the highest priority of Republican voters is that their leaders be “fighters,” not that they fight for a particular suite of policies. (Treating partisan hostility as an acceptable substitute for an agenda is how we ended up with a party that doesn’t do much.) If McCarthy isn’t going to fight by having a showdown with Democrats on spending, he’d damn well better have a showdown with them on something else.

So it’s hard to take this impeachment inquiry seriously as an earnest investigation. But we should try, for two reasons. One: Despite the immense Clown Quotient of the GOP conference, they could be onto something in suspecting corruption between Joe Biden and Hunter Biden.

And two: Contrary to conventional wisdom, I think they’ll benefit politically from this impeachment effort in the end.

When Nancy Pelosi announced an impeachment inquiry into Donald Trump without any action on the House floor four years ago, then-Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy was furious. His objection was procedural as much as substantive. “Speaker Pelosi can’t decide on impeachment unilaterally,” he tweeted. “It requires a full vote of the House of Representatives.”

On Wednesday Speaker Kevin McCarthy announced an impeachment inquiry into Joe Biden unilaterally, without a full vote of the House.

Confronted by reporters about his hypocrisy, he gave a shrewd answer: He’s simply playing by the rules that the other party foolishly created. Pelosi shattered a norm of the House by treating impeachment inquiries as a matter of royal prerogative rather than a majoritarian initiative. All McCarthy is doing now is following the new norm. Their rules, as populists on social media like to say.

The wrinkle is that, as recently as 12 days ago, he was telling Breitbart he’d insist on a full vote of the House to open an impeachment inquiry. His “their rules” change of heart in reaction to Pelosi’s ruthlessness four years ago apparently occurred sometime within the last week. What changed his mind on holding a vote, plainly, was the realization that he didn’t have 218 Republicans willing to move forward on impeachment. Too many moderate GOPers representing swing districts remain squeamish about trying to oust Joe Biden. If McCarthy was to gain some cover as a “fighter” before the coming shutdown showdown, he was left with no choice but to order an inquiry himself.

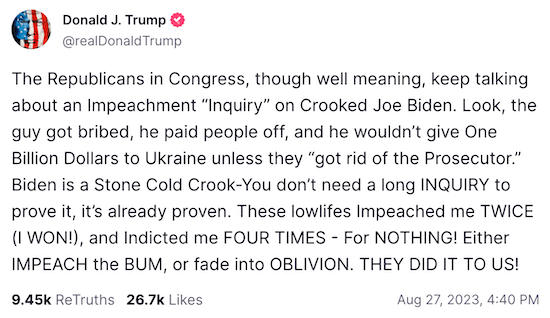

McCarthy’s feeble lie about what caused his procedural switch makes it hard to take him seriously. Ditto the fact that he and his deputies are obviously acting at Donald Trump’s behest.

Trump has reportedly been lobbying House Republicans to impeach Biden since before the midterms, expecting there’d be a sizable GOP majority this year to do his bidding. According to Rolling Stone, he was prone to asking cronies in Congress not whether they’d impeach Biden once they were in charge but “how many” times. He’s continued egging them on behind the scenes for months, per the New York Times, and was briefed recently on the new impeachment inquiry by the third-ranking House Republican, loyal toady Elise Stefanik.

As such, one could view this impeachment as a bookend to Trump’s first impeachment over Ukraine. Both incidents evince the same Republican M.O., using government power to undertake a fishing expedition for dirt on Joe Biden ahead of a presidential election. (Kevin McCarthy knows a little something about that too.) The 2019 impeachment was a production of Trump 2020, the 2023 impeachment is a production of Trump 2024.

And both incidents demonstrate the Trumpian logic of “their rules.” We must do it to them, for they did it to us.

The new impeachment inquiry is an act of revenge that’s years in the making, Jonathan Chait notes, and characteristic of a guy who once named “an eye for an eye” as his favorite Bible verse. McCarthy will desperately need Trump’s backing to hold onto his job if he makes a deal with Democrats to avert a shutdown, and he hasn’t done much lately to earn that support. So here he is, throwing his patron a bone by formally casting suspicion of high crimes and misdemeanors on his likely opponent next fall. How seriously can we take a process as transparently hollow and cynical as that?

There’s one more reason not to take the new inquiry seriously. There just isn’t much evidence (yet) against Joe Biden.

That’s a departure from historical precedent, our friend David French argues in a column published on Tuesday. Bill Clinton’s impeachment in 1998 got rolling only after evidence emerged that he’d lied under oath; Trump’s first impeachment took off after the transcript of his phone call with Volodymyr Zelensky suggested a quid pro quo; Trump’s second impeachment gained momentum after, er, the U.S. Capitol was sacked. By contrast, David writes, what McCarthy is doing amounts to “a fishing expedition. He’s unilaterally opening a rare inquiry into a sitting president not because of the evidence that does exist but rather because of the evidence Republicans believe might exist.”

There’s simply no impeachable offense (yet!) of which Biden stands accused that would require an official inquiry rather than regular oversight. Tell ‘em, Mitt.

But.

There is the small matter of the president having lied repeatedly about Hunter Biden’s business activities and his own involvement in them. There’s also the text Hunter sent his daughter in 2019 in which he wrote, “don't worry unlike Pop I won't make you give me half your salary.” Joe Biden used aliases to send and receive emails while vice president, it turns out, which is a transparency problem if nothing else. And meanwhile, House investigators have heard testimony from IRS whistleblowers alleging that the Justice Department went easy on Hunter on tax charges because of who his father is.

Is that enough to justify an impeachment inquiry? Probably not, for the reasons David outlines. Is it enough to take the House investigation and its potential to uncover wrongdoing seriously? Yeah, I think so. And if someone as skeptical of Republicans as me feels that way, chances are high that many undecided voters will as well.

Which brings us to the other critique of the impeachment inquiry: that it will hurt Republicans politically in the end.

I don’t buy it.

It’s conventional wisdom among political junkies my age that impeachments end up backfiring on the party doing the impeaching unless they’ve really, really got the goods. Conservatives learned that lesson the hard way when Bill Clinton’s popularity grew during the 1998 impeachment process and Republicans badly underperformed expectations in the midterm elections that fall.

The belief that impeachment is a political loser became so entrenched that George W. Bush managed to avoid it despite the public uproar over the missing weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. Democratic leaders at the time calculated that they’d do better by holding off and letting voters punish Republicans at the polls. They were right, as the results in 2006 and 2008 proved.

Even now, battle-scarred conservative operatives and pundits are warning that impeaching Biden could backfire. They might even believe it—although, as you may have noticed with the questionable “electability” arguments against Trump, moral qualms on the American right tend to be expressed nowadays as prudential concerns. To call Trump unfit for office or Biden innocent of impeachable offenses is to betray the cause, after all; to worry that nominating Trump or impeaching Biden will set the cause back is more acceptable, as it at least affirms one’s interest in total victory over the left.

In fairness, there are reasons for Republicans to fret that impeachment could hurt them.

For starters, a speaker who needs Democratic help to avoid a shutdown and possibly to save his speakership may find Democrats less than cooperative now that he’s moved to impeach their leader with a high-stakes election looming.

McCarthy will also have little choice now but to put his members on the record about impeachment in the form of a floor vote. (Pelosi eventually did so in 2019 when Democrats passed a resolution formally authorizing the Ukraine impeachment inquiry.) The same vulnerable swing-district Republicans whom he tried to protect by authorizing an inquiry unilaterally will be forced to either ratify or overturn that decision in a roll call vote. There’s no happy outcome: Either they’ll infuriate liberals in their home districts by supporting the inquiry or they’ll infuriate MAGA Republicans—and humiliate the speaker—by quashing it.

It gets worse. Having ordered this inquiry, it’s impossible to see how McCarthy avoids proceeding all the way to impeachment. “Once the House has begun the process, not impeaching Biden will look like a validation of the president to many rank-and-file lawmakers,” Punchbowl News recently and astutely observed. Not impeaching Biden after a formal investigation has been conducted would be tantamount to pronouncing him not guilty. Trump would flip his lid. The populist base would bay for McCarthy’s blood.

The only way out at this point is through. Vulnerable House Republicans will have to take at least one, and maybe more, no-win votes on this subject.

And yet … I still think the “impeachment will backfire!” doomsaying is weak.

2023 isn’t 1998. In 1998, there had been just one impeachment of a president in U.S. history—and one near-impeachment that was averted by Richard Nixon’s resignation. The process was viewed at the time as a measure so extraordinary and fractious that only a Watergate-level scandal could reasonably justify it. When the Clinton investigation didn’t reveal a scandal of that magnitude, voters reacted badly.

In 2023, impeachment is old hat. Three House inquiries in less than four years have reduced the process from a grave matter of state in the eyes of most Americans, I suspect, to standard partisan pugilism. There’s scant evidence, in fact, that House Democrats paid any real price at the polls for having impeached Trump twice. They did lose seats in 2020 after impeaching him the first time, but not so many as to cost them their majority; meanwhile, Democrats gained control of the Senate in the same cycle. Two years later, in the first election following Impeachment 2.0, they wildly overperformed expectations for a midterm, holding the Senate and barely losing their House advantage.

Relative to COVID and Trump’s general Trumpiness, I doubt either impeachment mattered to voters when they went to the polls.

We’re also more polarized along partisan lines in 2023 than we were in 1998, notwithstanding Republicans’ white-hot hatred of Clinton. Because the pool of swing voters was larger then, the risk of an electoral backlash to a flimsy impeachment was greater. Twenty-five years later, a sitting president’s job approval never rises meaningfully and durably anymore. Trump cruised along at 43 percent for most of his presidency, taking a small tumble after Pelosi announced her first impeachment inquiry in September 2019, fully recovering (and then some) within two months, then tumbling again in the thick of the pandemic and civil-rights protests a few months later.

Why would Biden be different? He’s been underwater for two years running, is widely viewed as too old for his job, and has clearly been waaaaaay too personally indulgent of the shady dealings of his shady kid. He’s not the most sympathetic defendant. He also happens to lead a party that’s spent five years playing legal and political hardball trying to “get” Trump, his likely presidential opponent. How affronted can swing voters plausibly be by the spectacle of House Republicans trying to “get” Biden in return?

Especially when you consider that those voters exist within a media ecosystem vastly more diverse and propagandistic than it was even 25 years ago. John Dean once said that his old boss Richard Nixon might have survived Watergate if there had been a Fox News at the time. In 2023 there are lots of Fox Newses—including the actual Fox News—more than willing to affirm voters in their suspicions that Biden is guilty or innocent as the case may be. There’s no need to change your view of the president and his antagonists in the House when you can change the channel instead.

There’s another problem for Democrats, as one of my Dispatch editors pointed out this morning. The Biden White House is conspicuously bad at answering legitimate criticism, often resorting to flat denials of wrongdoing buttressed by indignation that anyone could believe otherwise. Just yesterday some of his deputies took to social media to whine about the press’ concerns over the president’s age, and on Wednesday, one of his spokesmen scolded reporters in a memo by insisting that covering the impeachment saga in terms of “Republicans say X, but the White House says Y” would do a disservice to the American people.

Hunter and Joe did nothing wrong and you’re a closet MAGA if you disagree is a risky talking point if the impeachment inquiry turns up additional evidence of impropriety. Swing voters might resent being lectured that they should believe Team Joe rather than their own lying eyes.

Most of all, though, I think the inquiry will benefit Republicans by turning what might otherwise be a “referendum” election into more of a “choice” election. If voters go to the polls next fall believing that one candidate isn’t corrupt and the other really, really, really is, it risks making the race a de facto gut check on whether Trump should pay for his crimes. That’s a bad bet for Republicans.

But if voters go to the polls thinking one candidate is really, really, really corrupt and the other is also pretty corrupt, that might neutralize the issue of corruption—at least for the sort of right-leaning voter who deep down wants to cast his ballot for Trump but feels a pang of conscience about doing so. The impeachment inquiry is an invitation to those voters to lay their squeamishness aside and treat the subject of corruption as a wash. That’s a good bet for Republicans.

Maybe good enough to rescue those purple-district House GOPers who are themselves squeamish about impeachment, especially if Trump performs his usual trick of turning out low-propensity right-wing voters on their behalf.

Look at it this way: If the election ends up as a referendum on Trump anyway despite Republicans’ best efforts, impeaching Biden will have been a costless endeavor. Any voter who’s mad enough at the GOP for going after the president to vote Democratic next year is already mad enough at the GOP for nominating a coup-plotter and quadruply-indicted accused felon to vote Democratic next year. In other words, laying off Biden might not gain Republicans any votes—but it could lose them some by antagonizing Trump and his base of “fighters.”

So why not do it? It might not be ethical based on the available evidence, but this party dispensed with ethics long ago in the name of victory at all costs. Impeachment gets them a little bit closer to that victory.

If you appreciate what we’re doing here at The Dispatch, we have a small favor to ask: Forward this email to someone (or a few someones) in your life who might enjoy getting Boiling Frogs every day. Let them know why you’re a reader, and that they can click “sign up for this newsletter” at the top of the email. For the next few days, the members-only version of Boiling Frogs will be unlocked for all to read.

To do more of the kind of work we want to do, we need more members. And the best way to get more members is word of mouth from the people who know us best. Thanks for your help.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.