In April 2010, with Tea Party fever peaking on the right, Sen. Jim DeMint of South Carolina spoke admiringly to a group of activists about a rising star in the Republican Party. “I’d rather have 30 Marco Rubios than 60 Arlen Specters” in the Senate, he told them.

A lot has changed since 2010. But not everything.

Rudimentary math tells us that a Senate with only 30 small-government “true conservative” Republicans would produce legislation that’s vastly more liberal than a Senate with 60 RINO moderates in the mold of Specter or Susan Collins. A 70-seat Democratic majority would have the run of the place, the filibuster no longer a barrier to their most progressive ambitions. To Jim DeMint, the model of a “true conservative,” unchecked Democratic power was a price worth paying to purify the Republican Party.

He left the Senate two years later. Politico eulogized his political career aptly: “He wasn’t a legislator, has no signature laws to his name and has never been part of any major bipartisan negotiations.” We’ve grown accustomed to post-Trump populists like Marjorie Taylor Greene running for Congress despite evincing no interest in legislating, but DeMint got there first. By 2013, he was president of the Heritage Foundation; that year, his think tank panned the so-called “Gang of Eight” immigration reform proposal spearheaded by … Marco Rubio.

Today’s “true conservative” is tomorrow’s RINO.

DeMint told the audience in 2010 that he believed “principled, constitutionally centered Republicans can be elected anywhere in the country.” Last November we discovered that they can’t even be elected in Wyoming, not in a party where “conservative” and “RINO” have been redefined, respectively, to mean “blindly loyal to Trump” and not.

At last check, in December 2020, the allegedly “constitutionally centered” Jim DeMint was affixing his signature to an open letter calling on the legislatures in swing states won by Joe Biden to throw out the ballots and award their electors to Donald Trump. If you wanted to track the civic degeneration of the Republican Party in the career arc of a single person, you could hardly do better.

Still, there’s a common thread in his preference for 30 Rubios to 60 Specters and his preference for a “soft” coup to keep a proto-fascist in power. In both cases, DeMint didn’t sweat the logistics of building a governing Republican majority. The idea of Trump and the party needing to soften their pitch to swing voters in certain ways to win more elections seemed genuinely unthinkable to him. Better to stick to your guns and lose. And cry “fraud” as necessary.

A lot has changed since 2010. But not everything.

A political party can moderate only so much for the sake of winning before undermining its raison d’etre. But the logic of democracy points toward moderation: In a big country where policy views vary widely, the side that gains power will more often than not be the side that aims for the undecided movable middle.

Lately only one of our two parties seems to understand that.

Let’s not congratulate Democrats too exuberantly. For instance, the party hasn’t moved an inch off of its fanatic “no limits” position on abortion since Roe v. Wade was overturned last year. The politics of the issue favor pro-choicers for now, as voters recoil from aggressive restrictions pushed by red states. But when (if?) Republicans are pressured by election disappointments into enacting more moderate limits favored by the public, the focus will shift—hopefully—to liberal extremism on abortion. And then it’ll be the left’s turn for a DeMint-style gut check on how large they want their Senate caucus to be.

On other culture-war flashpoints, however, Democrats haven’t been as obstinate about maneuvering. Recently Biden has begun to steer toward the center on two issues that have caused his party grief at the polls.

Readers of The Morning Dispatch already know the details of Biden’s reversal on the new crime bill passed by the city council in Washington, D.C. The council wants to reduce penalties for some crimes, like carjacking, and to expand the right to a jury trial to even minor misdemeanors. The bill was too progressive even for D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser, who vetoed it, but the council overrode her veto. That left Congress, which has the authority to overrule local legislation, as the last hope to stop the new law. A bill that would do so passed easily in the Republican-controlled House but the Democratic Senate seemed a high hurdle, especially with Biden poised to issue a veto threat on grounds that the House bill interferes with D.C.’s right to govern itself.

Then came the surprise.

The bill is now expected to pass the Senate easily with upward of 70+ votes. Democrats are furious with Biden, although it sounds like they’re offended less by his support for the Republican legislation than by the fact that he didn’t announce his position until after House Dems had walked the plank and cast a tough vote in support of the D.C. law.

It was a tricky issue for the White House since statehood and self-governance for the district are a pet cause for many liberals—but not that tricky. Democrats are haunted by how badly they underperformed expectations in 2020 and broadly agree that “defund the police” sloganeering during the Black Lives Matters demonstrations that year is what did them in. Public anxiety about rising crime and the strongman appeal of his probable 2024 opponent has left Biden keen to undo the resulting political damage. Last year, in his first State of the Union address, he proclaimed: “We should all agree the answer is not to defund the police. It’s to fund the police. Fund them. Fund them. Fund them with the resources and training—resources and training they need to protect our communities.”

Once House Republicans made the new D.C. crime law a federal matter, Biden had to choose between placating his base by vetoing the House bill or reaching out to the center by signing it. He took the path toward victory, the one that would broaden his appeal.

He’s begun to tiptoe toward the center lately on another major Democratic liability, immigration. The ongoing fiasco at the border leaves him vulnerable to a Republican opponent whose political calling card is building a wall. Centrist analysts like Ruy Teixeira have warned Biden and his party that their political viability depends on escaping the left-wing “cultural bubble” in which an unsecured border is treated as a civic good. Lo and behold, on Tuesday morning the New York Times reported that the White House might reinstate Trump’s policy of detaining immigrant families who enter the country illegally, a strategy Biden ended after taking office. That would complement another new rule requiring asylum seekers from far-flung countries to seek refuge in nations they pass through instead of in the United States, another Trumpish initiative.

The new asylum policy brings Biden further into line with the balance of public opinion at the expense of crossing his own party. Among Democrats, a plurality want to see the number of asylum applicants increased rather than reduced. Among the overall public, it’s the opposite. Biden is tilting toward the latter.

In short, a politician who’s likely to be on the ballot next year is assessing his electoral weaknesses and taking steps to address them, however belatedly. Democrats have been bleeding votes among working-class Americans who find progressive positions on crime and immigration radical, alienating, and frankly weird. The White House’s new policies are designed to mitigate that. They’re learning from their mistakes. That’s how democracy works. In theory.

Which brings us to the other party.

Some Republicans are also trying to learn from their party’s mistakes. The last two years of Mitch McConnell’s career have been one long exercise aimed at convincing suburban swing voters that a movement led by you-know-who really is capable of governing sensibly and responsibly through compromise. Infrastructure? The GOP will work with you on that. Modest gun restrictions? They’ll work with you on that, too. Bolstering America’s ability to produce microchips? You’d better believe they’ll work with you on that. It’s a serious political party. Pay no attention to the orange man behind the curtain.

In fact, to give the devil his due, even the orange man is willing to throw centrist voters a bone now and then in the name of electability. His position on entitlement reform is undoubtedly more popular than the position of Republican leaders who preceded him, however grossly wrong he might be on the merits.

The problem for Trump and McConnell is that swing voters’ apprehensions about the Republican Party have less to do with extreme policies than with, well, extremism. As one CPAC attendee put it to a reporter for Bari Weiss’ site, “They’re scaring away the normal people.” There’s nothing McConnell can do about that because there’s nothing Trump wants to do about it.

You may have heard that the highest-rated host in cable news has chosen to revisit the subject of January 6 in a quixotic effort to convince American voters that that day was some sort of innocuous sightseeing tour, not a riot that ended with police officers injured and members of Congress fleeing for safety. You may also have heard that he’s being assisted in this endeavor by the Republican speaker of the House. Given the toxic politics of this subject for the GOP, “malpractice” doesn’t begin to scratch the surface of what’s happening. Tim Miller put it succinctly: “Kevin [McCarthy]’s decision to give this footage to Tucker leading to endless news cycles relitigating 1/6 and his own members staking out pro-insurrectionist positions has got to be one of the biggest political own goals in the modern history of the speakership.”

Less than 24 hours after Tucker Carlson aired his “fiery but mostly peaceful” revisionist history of January 6, congressional Republicans are already being cornered by reporters and pressed about it. GOP senators want no part of it, but the MAGA caucus in the House will recognize this as the DARVO opportunity of a lifetime and won’t be able to resist. Naturally McCarthy himself will be asked his opinion on whether he still believes January 6 was bad, and he’ll have no good options. If he says no, the swing voters McConnell has been cultivating will recoil. If he says yes, the fact that he made Tucker Carlson’s propaganda ploy possible won’t save him from the wrath of populists.

Care to guess where Mitch himself comes down in all this, incidentally? It’s no surprise.

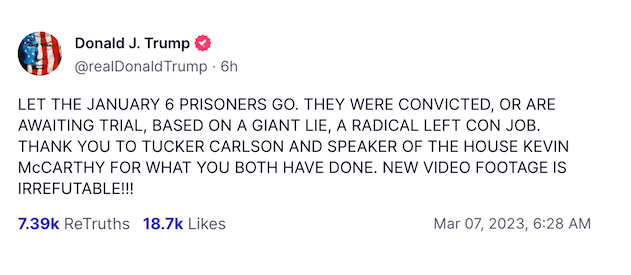

Fox News daytime has apparently had the good sense (or good legal counsel) to stay away from Carlson’s revisionism thus far. But the cretin who inspired the insurrection and who reportedly delighted in it doesn’t have that good sense, so he’s chosen to bear-hug his single biggest liability as a 2024 candidate.

“Going to be kind of funny to watch GOP candidates dance around acknowledging that the presidential frontrunner and the party’s semi-official media organ are more or less pro-storming-the-Capitol at this point,” Sonny Bunch of The Bulwark tweeted in response to Trump’s post. Dancing around it is the most we can hope for from the rest of the Republican presidential field; none of them (save maybe Chris Christie) will dare tell an audience of primary voters that January 6 was as bad as Trump’s enemies say.

If relitigating the Capitol riot from an anti-anti-insurrection point of view were the only example of Republicans failing to learn from their mistakes, it would be bad enough. It isn’t. Judging from his speech at CPAC this weekend, Trump’s campaign message this year will be considerably darker, stranger, and more vindictive than it was when he lost in 2020. Meanwhile, one of the worst performers in the 2022 midterms, Doug Mastriano, is reportedly now considering a Senate bid in Pennsylvania. Given how Republican primaries have devolved into DeMint-ish populist purity tests, it’s conceivable that Mastriano will win his party’s nomination despite having lost in a landslide in the 2022 gubernatorial and proved himself completely uncompetitive statewide.

There’s also news today that Trump is weighing his options for a running mate, and has a favorite.

Former President Trump is strongly considering picking a female running mate — and sees Kari Lake as a model for his vice-presidential pick, according to people who discussed the topic with him.

Why it matters: Trump is already gaming out the general election in November 2024 — and knows he has a massive weakness with the white suburban women he would need to beat President Biden.

Lake, a former TV anchor who lost her race for Arizona governor in November, meets Trump’s most important qualification for a No. 2:

She has shown she’s willing to defend him vociferously, no matter the issue or controversy.

Elevating a candidate to a national ticket after she lost a race she was supposed to win is one thing. Elevating that candidate in the dunderheaded belief that she’ll make you more electable, not less, is the definition of not learning from mistakes.

But then, maybe Trump is only giving his fans what they want. When CPAC held its straw poll on Saturday and asked attendees whom they’d prefer as his running mate, they didn’t say “Ron DeSantis.”

Imagine how Republicans would react if Joe Biden replaced Kamala Harris with Stacey Abrams on next year’s Democratic ticket. She ran for governor and lost, they’d say. What has that loser done to make us trust that she’d govern effectively if thrust into the presidency? It’s a strong point; that logic doubtless figured heavily in Biden’s decision to choose Harris over Abrams in 2020. He wanted to appeal to the broadest possible array of voters and knew that undecideds would feel more comfortable with a sitting senator than someone whose claim to fame was not conceding a gubernatorial election she lost.

But Trump and his supporters won’t apply the same logic to Lake. Why?

I have a theory that many grassroots Republicans don’t want to win elections anymore.

Well … maybe that’s too far. I think they’re generally indifferent about winning elections, let’s say, and for the same reason Jim DeMint was. Their commitment to their ideology is tribal more so than it is political. You can compromise when you view politics as a means to some policy end that you favor. But when, like faith, politics defines who you are, there can be no compromising on that. It’s an end in itself.

Which is how we get sorry spectacles like this.

A party that cared about winning would indulge Meijer if he refused to support Trump in 2024. He’s a centrist Republican eyeing a Senate run in a tough swing state, and he’s rich enough to self-fund. He’s a good candidate by any measure and would move national policy to the right relative to a Democrat. But if he reaffirmed his commitment to opposing Trump after voting to impeach him in 2021, he’d be a nonstarter in a primary. Winning elections is nice but not at the price of tolerating heretics.

If you could prove to populists that doubling down on the alleged innocence of January 6 protesters and Trump’s many other grievances and conspiracy theories would certainly cost them the 2024 election, I don’t know that it would rally them against him. The possibility that he’s an electoral drag on the party is relatively uncontroversial postmidterm, after all. He’s leading in primary polling anyway.

You don’t abandon your faith just because it’s unpopular. Better 30 Marco Rubios or Marjorie Taylor Greenes than 60 Arlen Specters or Mitt Romneys.

A few weeks ago Semafor asked a rhetorical question to which we all know the answer: “Could Nikki Haley take down the Confederate flag today?” After a white supremacist murdered nine black churchgoers in Charleston in 2015, then-Gov. Haley famously ordered the rebel flag removed from the statehouse grounds, a small gesture of sympathy and reconciliation to her state’s black residents. At the time, that move raised eyebrows. Today I think it’d be treated by populists as a capitulation to “the woke mob” that’s disqualifying in a national candidate—again, even if you could prove to them that it boosted the GOP’s appeal to African Americans and swing voters.

I grant again, as I did earlier, that a political party can moderate only so much for the sake of winning before undermining its raison d’etre. But if it turns out that moderating on the size of government and the projection of American power abroad is fine whereas moderating on the removal of Confederate symbols isn’t, it raises a question of what that raison d’etre might actually be.

A great irony in all this is how it confounds the conventional wisdom about negative partisanship. Republicans vote Republican mainly because they fear and loathe Democrats and Democrats vote Democratic because they fear and loathe Republicans, or so the theory goes. And I think it’s true for the left: A lackluster candidate like Joe Biden got the most votes in American history in 2020 because of who his opponent was. His recent betrayal of progressives on crime and immigration will be tolerated for the same reason, with no hint of a serious primary challenge. The terror of a second Trump term and the prospect of further liberal policy gains in a second term are the concrete that binds the Democratic coalition together.

But it’s not very true of Republicans, is it? If the populist right believed its own nonsense about “Flight 93 elections,” the 2024 primary would already be decided. Trump and his political baggage would be unceremoniously tossed out of the rear of the plane and a more electable populist like DeSantis would be escorted to the cockpit. Instead, in primary polling thus far, Trump remains at the controls.

I think populists ultimately care less about defeating the libs than about owning them. And no one antagonizes liberals quite like Trump does.

Frankly, they might even quietly prefer minority status in government. The minority in Congress spends its time blaming the majority for all of the country’s woes, with no obligation to produce a policy agenda of its own. That’s populism all over. If, like Trump, you enjoy politics because it’s an exalted platform from which to air your grievances, you might find the minority quite comfortable. If, like Biden, you have certain policies you’re keen to enact, only the majority will do. One of them learns from their political mistakes in the name of electability, the other doesn’t. Guess which.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.