Seasoned consumers of political news, particularly those who lean right, are used to asking themselves: “What are they not telling us?”

Media bias is a thing, as the kids say. Sometimes it involves outright distortion of the truth. Often it’s more subtle, omitting a fact that might otherwise throw the story into a less politically useful light.

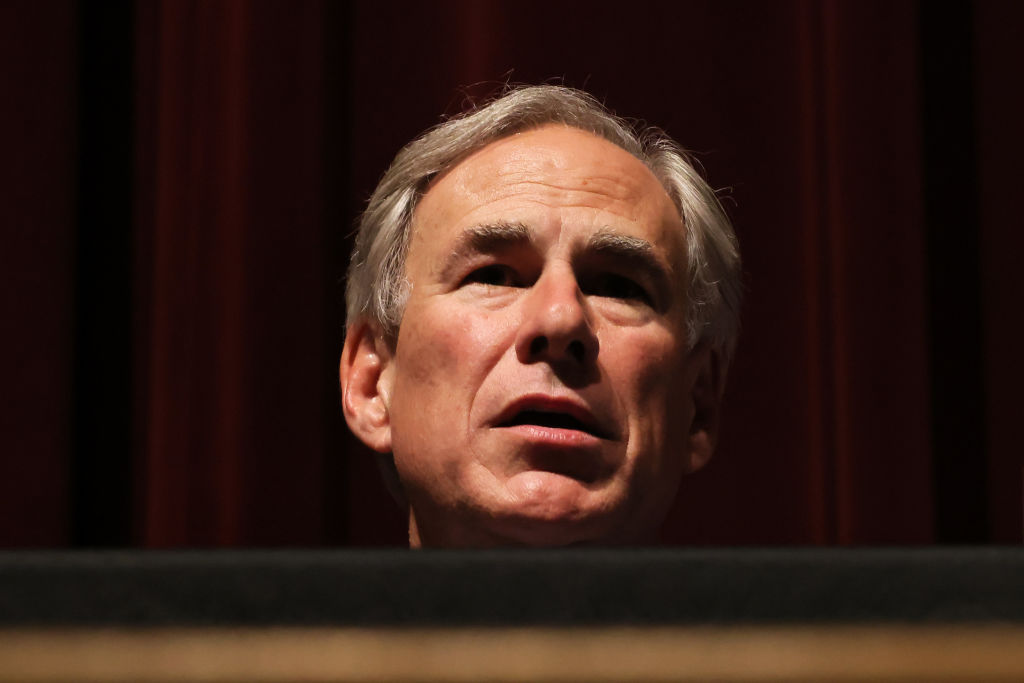

Reading the coverage this week of Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s desire to pardon Daniel Perry, my suspicion that they might not be telling us something important approached paranoia. There had to be more to the story.

But if there is, I can’t find it. It’s as bad as it looks.

Abbott posted this on Saturday, just one day after Perry was convicted of murder in Austin.

That statement is unusual in more than one way. For starters, Abbott isn’t prone to showing mercy to convicts. Per the Texas Tribune, he doled out a grand total of 17 pardons between 2020 and 2022, “all for lower-level offenses, including theft, providing alcohol to a minor, assault by contact, burglary of a vehicle, credit card abuse and illegally carrying a firearm.”

And Abbott typically announces his pardons around Christmas. For the governor of Texas to spring into action in April, to excuse a convicted murderer lest he spend so much as one extra unearned day in prison, you’d think the injustice in Perry’s case must be momentous.

But that’s another unusual thing about his statement. There’s no specific allegation of misconduct. The closest Abbott gets is accusing the jury and local district attorney of having “nullified” the state’s “stand your ground” law, which smells suspiciously like code for “reached a verdict that offends my political prejudices.”

Let’s back up.

On July 25, 2020, a Black Lives Matter protest was held in downtown Austin. Garrett Foster was among the demonstrators. He was carrying an AK-47 “draped on a strap in front of him,” according to eyewitnesses who spoke to the New York Times afterward. He was entitled to do so, as Texas law permits open carry.

Perry, a sergeant in the Army, spent that evening in Austin driving for Uber. Shortly before 10 p.m., he turned onto a street where protesters were marching. Moments later, Foster would be dead.

Perry told police that he was distracted by texting a friend before encountering the protesters and looked up to find himself surrounded, with people banging on his car. “Perry said Foster wanted to talk to him, so he rolled down his window,” the Austin American-Statesman reported. “Foster mumbled something at him and then raised his weapon, Perry said.” In a flash, Perry pulled his own gun and fired several shots at Foster, killing him. Classic self-defense, particularly in a “stand your ground” state.

But that’s not how it happened, witnesses insist. “The driver intentionally and aggressively accelerated into a crowd of people,” one told the Times. “We were not aggravating him at all. He incited the violence.” Another pointed to the squealing of the tires as evidence that Perry had hit the accelerator, possibly impatient at his path being blocked and hoping to force the demonstrators to clear a path.

And more than one witness claimed that Foster never raised his weapon. “He was not aiming the gun or doing anything aggressive with the gun,” that second witness told the Times. “I’m not sure if there was much of an exchange of words. It wasn’t like there was any sort of verbal altercations. He wasn’t charging at the car.” Foster’s wife, who was right next to him when he was killed, also insists that his AK-47 was still in the strap on his chest and pointed downward, not at Perry.

To my eye, the lone photo of the incident bears that out. Foster’s gun appears to be tilted toward the ground with the stock up beside his right ear and the barrel obscuring his left forearm at his side.

Notably, Perry himself suggested initially that Foster wasn’t pointing the rifle at him. “I believe he was going to aim at me. I didn’t want to give him a chance to aim at me,” he told police afterward. If that’s enough to constitute self-defense in an open-carry state, any moment of hostility between two armed people should lawfully entitle one to preemptively shoot the other.

An obvious rejoinder at this point is to note Perry’s apparent lack of motive. He stumbled into a tense situation; in the chaos he might have misunderstood Foster’s intentions with his gun; he protected himself. It’s not like he was looking to shoot anyone.

Are we sure, though?

[Before the shooting] Perry had conversations with friends on social media and on his phone that showed he was angry at protesters. He told a friend he had watched a video of a protester getting shot in Seattle after pulling someone out of a car. Perry said that since that shooting happened in Seattle the gunman would probably go to prison, but “if it was in Texas he would already be released.”

Perry also had another conversation with a friend on social media saying he might be able to “kill a few people on my way to work.” “They are rioting outside my apartment complex,” his message said. The friend responded saying, “Can you legally do so?” Perry replied, “If they attack me or try to pull me out of my car then yes.”

…

Perry also told a friend on social media in May 2020 that he might go to Dallas to “shoot looters.” He later texted that friend that he was at a protest in Dallas in June 2020 and was “packing heat.” “I wonder if they will let me cut off the ears of people who decide to commit suicide by me,” Perry said.

In yet another social media post, Perry complained about protesters putting cops in danger and advised to “just keep shooting them until they are no longer a threat.”

One reads all of that and wonders whether he stumbled into his encounter with the protesters or whether he went looking for trouble. It’s important, and not just as a matter of moral culpability: By law, Texas’ “stand your ground” defense doesn’t apply if the defendant provoked the person whom he ended up shooting.

In other words, if the eyewitness who believes Perry accelerated deliberately into the crowd is correct, arguably it’s Garrett Foster who had the right to stand his ground and use force against Perry rather than the other way around.

Why is this man being pardoned?

Perry’s trial lasted eight days. Dozens of people testified and “much forensic evidence” was produced. The jury deliberated for 17 hours.

Greg Abbott did not attend, nor did he watch it on television. It wasn’t televised.

There is, in short, no reason for him or for us to second-guess the jury or conclude that Perry didn’t get the process he was due. The closest thing to an allegation of misconduct came from a police investigator who believed the shooting was justifiable homicide and claimed the D.A. asked him to “scale down” his presentation of evidence to the grand jury. But the D.A. denies it, and the investigator was called by Perry’s lawyers as a witness for the defense at trial. The jury got to hear his testimony. They found Perry guilty beyond a reasonable doubt anyway.

I can’t imagine what legal reason there might be for the governor to react to that by calling for an immediate pardon, essentially overruling the verdict before appellate courts have had a chance to hear any of Perry’s objections. But I can imagine a political reason.

This segment aired on Fox News a few hours after Perry was convicted. It’s worth watching in full.

If anyone ought to be asking “What are they not telling us?” of the media they consume, it’s the avid Fox News viewer. That’s especially true of Fox News primetime, as recent developments have reminded us, and truer still of Tucker Carlson, whose televised pronouncements should be greeted with skepticism even according to Fox’s own lawyers.

Listening to Tucker’s account of the shooting, you might imagine Perry sitting in his car, minding his own business, only to find a progressive “mob” out for blood suddenly descending upon him. Before he knew it, Foster had “raised” his rifle outside the driver-side window, leaving our hero with no choice but to defend himself from another crazed, menacing left-winger. It’s a perfect made-for-Fox narrative, right down to the fact that Perry is a military serviceman.

For the record: So was Garrett Foster.

Carlson did get one thing right: “In the state of Texas, if you have the wrong politics, you’re not allowed to defend yourself.” That’s an absurdity when applied to Perry, who had the good fortune to murder a leftist in a state so right-wing that the governor couldn’t wait a day to pardon him, but it’s incisive and true when applied to Garrett Foster.

Tucker’s two-minute whinge on Fox News on Friday kickstarted a round of caterwauling in right-wing media about the alleged injustice perpetrated against Perry. Kyle Rittenhouse, who became a populist folk hero when he successfully claimed self-defense after shooting several leftists during a riot, pleaded for clemency for Perry. Texas’ lieutenant governor, Dan Patrick, appeared on Fox and repeated the false claim that Foster had pointed his rifle at Perry.

Abbott has won three gubernatorial elections in Texas, all by double digits, and was safely reelected to a new term less than six months ago. He has no electoral reason to fear the wrath of Fox and its online media barnacles. But the Trump-era habit of catering to the right’s most obnoxious figures is now so reflexive that he moved to gratify them almost instantly with the prospect of pardoning Perry. I’d be curious to know how many times in the history of the United States a governor has proposed clemency for a convicted murderer as quickly as Abbott did in this case.

All of this is exactly what it looks like, no? What else can it be?

Either Abbott is suggesting that Perry’s account of what happened is so compelling that it should override the considered judgment of the D.A., a grand jury, and a trial jury—which is unlikely—or he means to signal that anyone who kills a left-wing activist in Texas should and will be excused provided there’s a fig leaf of self-defense. “You only valorize Garrett Foster’s killer if you’ve convinced yourself that Foster deserved to die,” writes Radley Balko, whose post about Abbott’s pardon is worth your time:

Foster’s death has become the latest front in the culture war. So he must be flattened. He gave a sh*t about racism and injustice, so he must [be] portrayed as a left-wing terrorist. Perry, meanwhile, loathed the protesters and Black Lives Matter, so his actions must have been virtuous and true. The DA who prosecuted Perry is prosecuting a man the right has deemed a martyr, so he can only be a lawless, Soros-funded activist. And any jury who convicted an ally like Perry can be nothing more than a mob of Austin liberals in search of a conservative to persecute.

…

For all the degeneracy on the political right in the Trump era, this is what I find most alarming—the dehumanizing of political opponents to the point where violence isn’t merely justifiable, it’s almost a moral imperative. Their opponents aren’t just wrong, they’re criminal. People accused of crimes aren’t just presumed guilty, they deserve to be abused by police. Immigrants aren’t just crossing the border illegally, they’re mostly rapists and criminals. Protesters aren’t merely misguided, they should be flattened by big-ass trucks.

Whether Garrett Foster actually threatened Daniel Perry doesn’t warrant so much as a footnote in the populist calculus on whether to grant a pardon. Foster was armed; he was a progressive at a progressive protest; Perry hates protesters and says he felt threatened. QED.

For my friends, everything. For my enemies, the law.

If Balko is correct that the right now derives its sense of justice in politically charged confrontations purely from the identities of victim and offender, we should be able to find examples of them treating their own activists antithetically to Foster. That is, if you participate in a protest, even a violent protest, and suffer as a result, you’ll be granted martyrdom so long as your protest serves a right-wing cause.

And we do, in fact, find examples like that.

Abbott’s pardon would give the moral instinct that violence is lawful depending on whether it’s used for or against “us” the force of law. It’s an exceedingly Trumpist attitude for a man who isn’t really a Trumpist. He was sworn in as governor before Trump came down the escalator and, as a young lawyer, was handed a seat on the Texas Supreme Court by none other than Gov. George W. Bush. He knows better than to delegitimize the criminal justice process simply because it played out in a liberal jurisdiction like Austin.

But Abbott is an ambitious conservative in an increasingly nationalist party and nationalists are consumed by the belief that their “tribe,” however they define it, should dominate all others. “There must be ingroups whom the law protects but does not bind, alongside outgroups whom the law binds but does not protect” is how Damon Linker describes the logic of pardoning Perry, summarizing a well-known critique of how conservatives allegedly view the legal system. That critique used to be unfair, he allows, but post-Trump it seems apt. The governor of the country’s second-biggest state is preparing to excuse a member of the ingroup for killing a member of the outgroup because the ingroup is offended that he should face any sort of legal consequences in a state it dominates politically.

Put simply: If you can’t shoot a BLM protester in Texas and get away with it, even in Austin, why elect Republicans in Texas in the first place? Former judge Greg Abbott, who likes his job as governor and might like to be president someday, considered the prospect of a future Republican primary and adopted that logic as his own. Reluctantly, perhaps, but no less depraved for its reluctance.

It’s an unusually low moment for a party that increasingly revels in its own deplorability. There will be more such moments, and worse.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.