You’ve seen The Poll, I assume.

The Poll is the hottest topic in political commentary. In the not-quite-three days since it was published, incisive glosses on it have appeared already at prestige shops like the New York Times and Washington Post.

If you’ve grown pessimistic about the future of America, and haven’t we all, The Poll is here to prove quasi-mathematically that your instincts are correct.

The Poll is also, in an important way, nonsense.

The Poll was conducted by the Wall Street Journal, which wanted to know how Americans are feeling about core values like patriotism, community, religious faith, and having children. The short answer is “not great.” The longer answer is “not great, and drastically worse than only a few years ago.”

Those results had something for everyone. A right-wing catastrophist might never find more compelling evidence that the country is going to hell in a handbasket. A left-wing catastrophist might feel vindicated in believing that America’s failure to remedy injustices various and sundry had finally, and surprisingly suddenly, caused the people to abandon all hope.

The “suddenly” part is the nonsense part.

Pollster Patrick Ruffini pointed out that surveys of this type have typically been conducted by telephone, requiring respondents to interact with a live interviewer. But The Poll was conducted online, requiring them to interact with a computer. Human beings, it turns out, are less likely to admit to other human beings that they’re not feeling patriotic or religious or inclined to have kids. A live interviewer might judge you for having those feelings, after all. A machine will not.

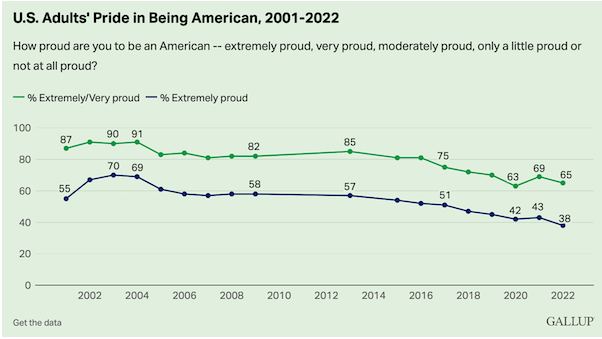

What looks like a sudden collapse in traditional values, in other words, is almost certainly an artifact of using a different polling methodology. For a more plausible trendline, Ruffini pointed to this Gallup poll published last summer showing no tailspin in patriotic sentiment since 2019.

If there’s been no tailspin with respect to patriotism, there’s probably been no tailspin with respect to other core values since 2019 either.

But if The Poll’s findings are overstated, they’re still sobering. It’s plausible that support for core values has dropped a bit over four years and quite likely, per Gallup’s data, that support has trended incrementally worse long-term. If Ruffini is right that the Journal’s results are more accurate than in years past because of its online methodology, then fewer than 40 percent of Americans now find patriotism, religion, community involvement, or having children “very important.”

Sobering. And instructive on the recent evolution of the country’s two political parties, especially on the right.

Age matters more here than simple partisanship.

There are enormous gaps in The Poll between adults aged 65+ and adults under 30 on whether patriotism (36 points) and religion (24 points) are “very important” to them. Senior citizens even lead on the question of whether having children is “very important” despite the fact that, unlike young adults, their child-raising years are long behind them.

To ask why young Americans should feel so alienated from the values of their elders is to take a political Rorschach test. There’s no wrong answer, really, and scarcely any limit on “right” ones. Disillusionment with the Iraq war; professional disruption from the Great Recession and the pandemic; psychological disruption from social media; panic over climate change and regular mass shootings; frustration over college debt, unattainable homeownership, and a rising cost of living; progressive dogma assuring them constantly that America has never been worse; Trump, Trump, and more Trump in their news feed 24/7—seemingly proving the progressives right; and endless partisan gridlock paralyzing the country from dealing meaningfully with any of its problems. Their young adulthood has been a lot rougher than mine was.

Now we’re about to toss them into the octagon with AI and tell them to outcompete super-intelligent machines for lower-level white-collar jobs. If you had all of that on your back, you too might lose some faith in the glorious promise of America.

Philip Bump made a shrewd point about the age divide over core values in a column yesterday at the Washington Post, keying off something Trump said in one of his recent campaign videos. Trump was boasting about having eliminated the federal estate tax on farms, allowing farmers to leave their property to their children tax-free. “But if you don’t love your children so much,” said Trump, “and there are some people that don’t—and maybe deservedly so—it won’t matter, because, frankly, you don’t have to leave them anything.”

It’s a joke, Bump allowed, but of the kidding-on-the-square variety. “A lot of Trump supporters really are wary of their own kids and grandchildren,” he argued, and ain’t it the truth. They’ve watched young adults in their own families vote for Barack Obama, cheer on the expansion of gay and trans rights, and embrace alternative sexual identities themselves. (Nearly 1 in 5 members of Generation Z now identifies as LGBT.) The average grandparent is far more likely than their grandchild to be religiously affiliated as well. Someone who came of age decades ago expecting to graduate high school, get to work, marry, and have children in short order may find their descendants single, childless, and still in some form of school well into their 20s, if not longer.

Older Americans, in short, may find young America culturally alien to a greater degree now than at any point in the past 50 years. Even in the tumultuous 1960s, the last great cultural battle between young and old, more than 85 percent of the population was white while 90 percent identified as Christian. Today even that common ground between generations has shrunk: Those numbers are 58 percent and 63 percent, respectively. Between 2010 and 2020, America’s white population declined in raw numbers for the first time in U.S. history.

That’s a lot of cultural displacement for the modern aging white majority to cope with, especially when it’s reflected in repeated political disappointment. The more conservative candidate has lost the popular vote in every presidential contest save one since 1992, a period that saw the first black president in American history elected with overwhelming support from the growing nonwhite minority.

A majority that’s losing its grip culturally and politically may, in its desperation, react in radical ways.

Ross Douthat considered that radicalism in his column today at the New York Times, which naturally also touches on The Poll. He offered a sort of unified field theory of modern American politics in which the left won the culture war (more or less) and both sides are miserable because of it. Despite the fact that polls show right-wingers are happier with their lives than left-wingers are, Douthat notes, it’s the right more so than the left that seems to be having a political nervous breakdown. Why?

If you yourself feel secure in your own values, confident that yours is a life well lived, but the society around seems to swinging rapidly away from those values, it’s natural to be baffled by the shift, to feel that something is badly out of joint, to decide that the entire system needs some sort of hard reboot. And it’s easy even to fall into paranoia and conspiracy theory, because it seems so unfathomable that so many of your fellow Americans would be abandoning the tried-and-true; there must be more to it than just a national change of mind.

…

Where does conservative politics go without a traditional cultural foundation to conserve? To subcultural retreat, maybe—but if you don’t think the walls will hold, if you want a politics of restoration, it will be inescapably radical in a way that the conservatism of thirty years ago was not. And since nobody—not the policy wonks trying to grope their way to some new form of right-wing political economy, not the online influencers selling traditionalism as a lifestyle brand—really knows how to do a restoration, how to roll back alienation and disaffiliation and atomization, it isn’t surprising that conservative politics would often be a car-wreck, a flinging of ripe fruit against a wall, no matter how happy individual conservatives claim to be.

Older white right-wingers spent 36 years from 1980 to 2016 believing that the gospel of limited government would create a country that’s more socially conservative in its respect for core values, not just more fiscally conservative. In the end they found they’d lost ground culturally, politically, and demographically.

In hindsight, it should have been obvious that nationalism was next.

Some commentators who regard nationalism more highly than I do would define it as “patriotism on steroids” or “patriotism inflamed.” I think that’s nonsense. It may be sincere, but many neoconservatives were sincere in believing that illiberalism can be eradicated by force and many communists were sincere in believing a world can be built in which no one wants for any necessity.

Ideologies behave differently on the ground than they do on paper.

I think nationalism is tribalism disguised as patriotism. It concerns itself with this question: Who, primarily, is the nation for?

In a nation where different tribes jockey for power, which tribe should rightly rule the others?

Five years ago Marco Rubio published a ridiculous yet well-meaning op-ed proclaiming that “Trump Is Right About Nationalism.” His task, plainly, was to redefine the American right’s newest ideological fad in more virtuous, traditionally pluralistic terms. And so he worked up the nerve to write passages like this: “President Trump is right to embrace the label ‘nationalist,’ because a true American nationalism isn’t about a national identity based on race, religion or ethnicity. Instead, it is based on our identity as a nation committed to the idea that all people are created equal, with a God-given right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Does that sound like Trumpism to you? We’re one unified people, bound together by our commitment to classically liberal values?

Or does telling four nonwhite congresswomen, all of whom are American citizens and three of whom are natural-born, to go back where they came from seem truer to the spirit of the movement?

For the first time in my life as far as I’m aware, a current Republican member of the House identifies not just as a nationalist but as a “Christian nationalist.” And she’s no random backbencher; she’s a good friend of the speaker and of the leader of her party and enjoys an exceedingly high public profile. In a poll published last year, 61 percent of Republicans agreed with her that the United States should be declared a “Christian nation” even though 57 percent also agreed that the Constitution doesn’t allow it.

The rise of Christian nationalism was predictable in hindsight, I think, just as it was predictable that white nationalists would galvanize online behind Trump in 2016 (and, years later, dine with him at Mar-a-Lago). Respectable mainstreamers like Rubio may choose to pretend that nationalism is whatever they’d prefer it to be, but the movement’s rank-and-file frequently tip their hand about the tribalism that motivates them in how they label themselves. If you’re worried about Christians and/or whites being culturally displaced and deprived of their right to rule America’s other tribes, chances are very good that you think of yourself as a nationalist.

That’s also why nationalism tends to look inward at its domestic enemies before concerning itself with foreign adversaries. Trump and his populist media acolytes will talk a good game about China and Xi Jinping but you’ve never heard them sound half as venomous about the Chinese Communist Party as they routinely sound about Democrats. Which makes sense: China, after all, has nothing to do with the essential question of “Who, ultimately, is America for?” No one despises their country as much as nationalists do when their tribe is out of power.

Through that lens, The Poll really does seem like a skeleton key of sorts in unlocking the state of the right. If you regard younger Americans as foreign culturally in their alienation from traditional values like patriotism and religion and foreign intrinsically by race, origin, or sexual orientation, nationalism will appeal to you as a last-ditch attempt to protect your tribe’s pride of place as the march of time risks making your displacement irreversible. Traditional conservatives who complain about Ron DeSantis resorting to state power to try to reverse the right’s cultural losses “don’t know what time it is,” nationalists like to say. The hour is late.

This explains why the Republican Party no longer has a political platform, no longer feels very strongly about democracy, and no longer views an attempt to overthrow the government as disqualifying in a presidential candidate. They’ve come to believe it’s a lost cause trying to persuade their fellow citizens of the rightness of their views. All that’s left is preserving tribal power, by any liberal or illiberal means necessary, as the younger alien tribes grow larger and stronger.

I wonder if left and right have begun to polarize around the issue of patriotism.

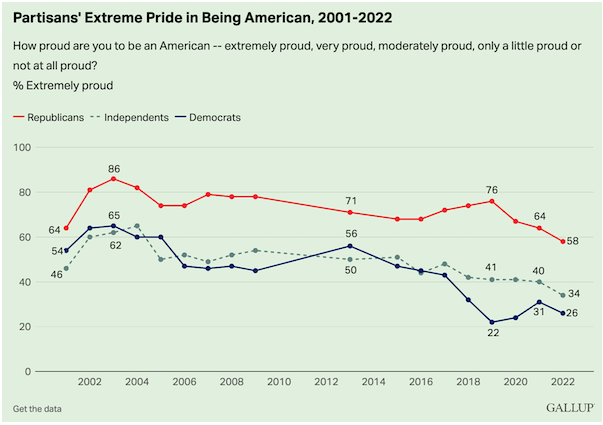

There’s always been a gap between them, of course. Look again at Gallup’s poll from last year and you’ll find dating back to 2001 that Democrats have never polled higher than Republicans when asked whether they’re extremely proud to be American. Since 2006, the largest share of Democrats to say so is smaller than the smallest share of Republicans to say so.

There’s a huge gap in the Wall Street Journal poll, i.e. The Poll, as well. Just 23 percent of Democrats say patriotism is “very important” to them versus 59 percent of Republicans who say so. One wonders how many young progressives have watched Trump and his fans festoon themselves with flags in their nationalist tribalist cause and concluded that they want no part of such “patriotism.”

There’s circumstantial evidence of it in Gallup’s results, perhaps. The share of Democrats who described themselves as “extremely proud” to be American declined only a bit between 2001 and 2016 but the bottom dropped out in Trump’s first year as president.

Candidly, I sympathize. I feel much less warmly about America than I did in the Before Times. But I remember Matt Yglesias writing recently about the pressure from the left on young liberals to adopt a “depressive affect” in response to their tribulations—global warming! guns! Trump!—and wonder how that might carry over to views on patriotism. If it’s a betrayal of the cause to so much as smile amid progressives’ many disappointments, it must be high treason to call yourself proud of your country. Why, to love America is to practically declare yourself a reactionary.

If left and right were polarizing around patriotism, though, you’d expect the share of Republicans calling themselves “extremely proud” to be American to have skyrocketed during the Trump years and maybe even to have remained aloft during the Biden era as a rebuke to the unpatriotic left. It did not. The largest share of GOPers to say they’re extremely proud during his presidency was a few points smaller than the share who said so in 2009, during the first year of Barack Obama’s presidency.

Maybe the trials of the pandemic and the Biden presidency have suppressed right-wing enthusiasm for America temporarily, or maybe Trump’s endless badmouthing of the country for his own political ends has begun to penetrate the conservative consciousness. If you’ve become convinced that U.S. elections are rigged against Republicans and the “deep state” is conspiring against Republicans and January 6 was some sort of elaborate false-flag to make Republicans look bad, I dare say it’s rational for you to question your loyalty to your country.

In fact, just 38 percent of Republicans said having children was “very important” in The Poll compared to 26 percent of Democrats, a smaller gap than probably anyone expected. For very different reasons, lefties and righties may be convincing themselves that this isn’t a country worth bringing children into.

Or maybe Douthat is right that both parties in modern America are unhappy with our current arrangement, in which the aging right fears displacement by the younger left while the younger left feels miserably devoid of purpose as it goes about displacing the aging right. The left can’t find happiness in bougie pleasures like faith and family, for the reason Yglesias gave, and it’s getting harder for them to find meaning in grand ideological conflict. The battle for civil rights was won decades ago and the battle for gay rights nearly a decade ago, forcing the left to content itself with the far more boutique cause of trans rights. Alexander wept when there were no worlds left to conquer; perhaps young progressives sympathize.

Either way, although the left traditionally has crusaded for “progress” and met resistance from a conservative cultural establishment, lately the establishment has grown left-wing culturally while the right has committed to insurgency, itself a form of displacement that feels unfamiliar and uncomfortable to both sides. It would be heartening to believe that we’ll return to the natural order soon, but demographic trends are what they are and you’ve seen the Republican primary polls lately. Buckle up.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.