Dear Capitolisters,

Frequent readers of this newsletter and those who know me IRL—two somewhat mutually exclusive groups for reasons we need not explore today—know I’m a pretty optimistic guy. Eco-doomerism, economic declinism, authoritarian hegemony, and other trendy pessimisms rarely find my warm embrace. But there are exceptions to my generally sunny outlook (beyond daylight saving time, expiration dates, and sloppy nachos, I mean), and last week’s U.S. Census Bureau projections definitely hit on one:

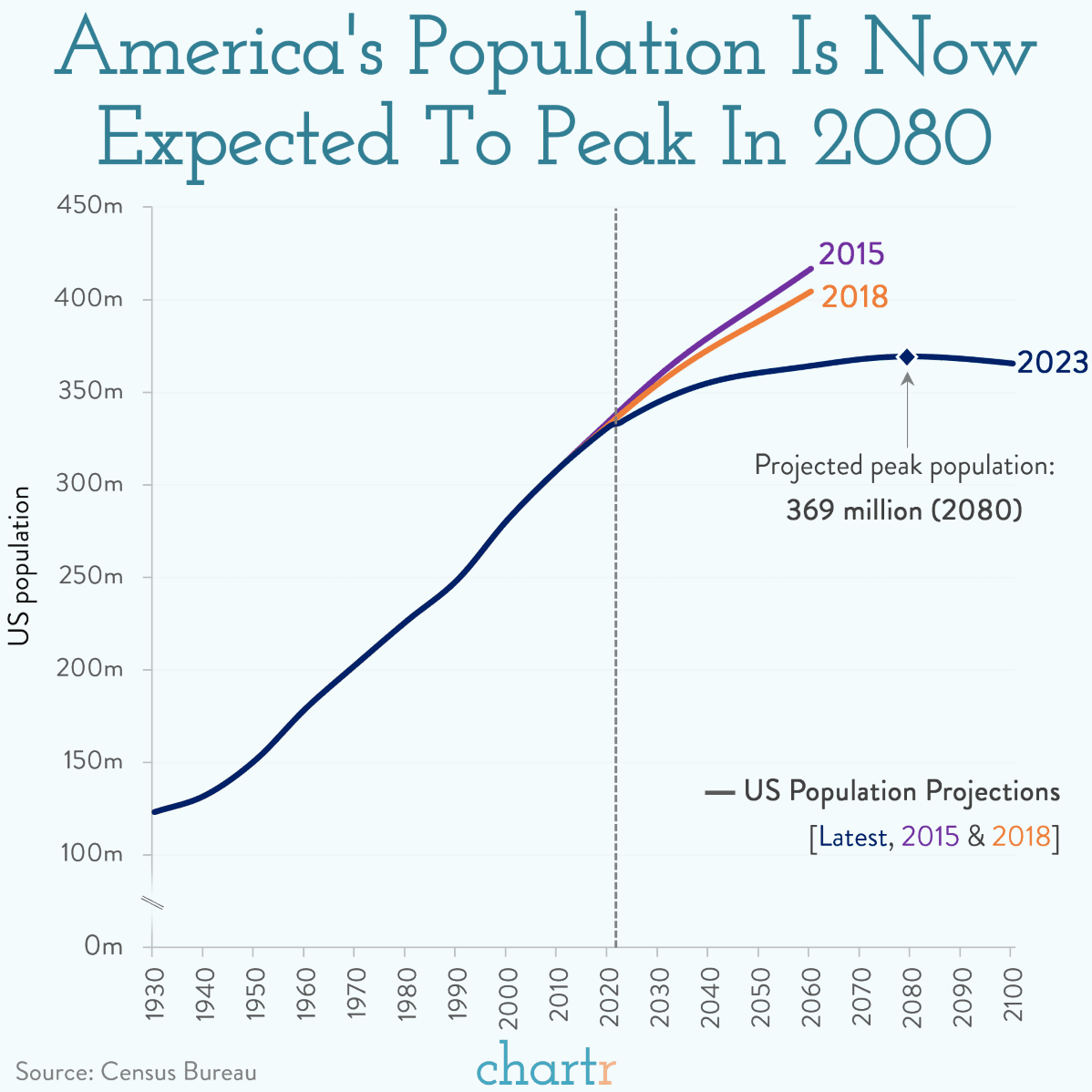

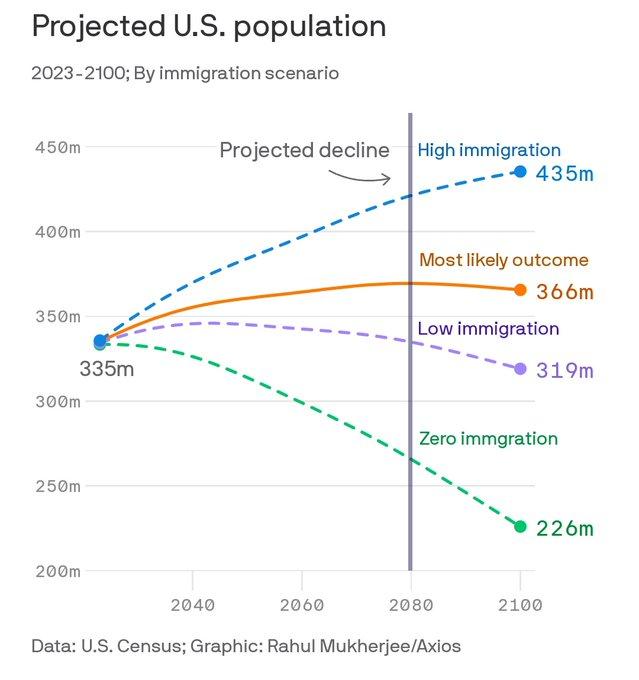

Projections out this week from the Census Bureau see America’s long streak of expansion grinding to a halt by the 21st century’s end. Indeed, the US population could be shrinking by as early as 2080, after peaking at 369 million, in the bureau’s central scenario. … This marks the first time that the bureau has forecast a decline for the coming decades — with the only other recorded population decline in the US occurring in 1918, amidst a deadly Spanish flu outbreak and a World War. By contrast with 2015’s and 2018’s optimistic outlooks, the stark shift in 2023’s projection reflects a decline in birth rates, higher death rates (due to an increasingly aging population, as well a COVID-related spike), and a reliance on immigration as a driving factor for growth.

It isn’t exactly news that developed economies around the world will face various demographic challenges in the decades ahead, as their populations get older on average. Still, the new Census Bureau estimates are notable in showing just how the United States’ already aging population has combined with new fertility and mortality (especially COVID-19) issues to further crimp the future U.S. population and workforce—and in showing how U.S. policy could affect that future.

Some of the Headwinds Facing a Graying America

As we’ve already seen in places like Japan, Germany, and Italy, a graying and (eventually) shrinking America will face various economic challenges. For starters, an aging society likely means lower economic growth. One recent study examined U.S. demographic changes between 1980 and 2010 and found that each 10 percent increase in the share of the U.S. population age 60 and older decreased per capita GDP growth by 5.5 percent—a decline driven by both decelerating productivity and, to a lesser extent, employment. Worker compensation and wages also declined. Overall, the authors calculate that “population aging reduced the growth rate in GDP per capita by 0.3 percentage points per year during 1980–2010,” and that, based on demographic projections at the time, this decade’s aging population could reduce GDP growth by another 0.6 percentage points per year. Other studies have found similar things.

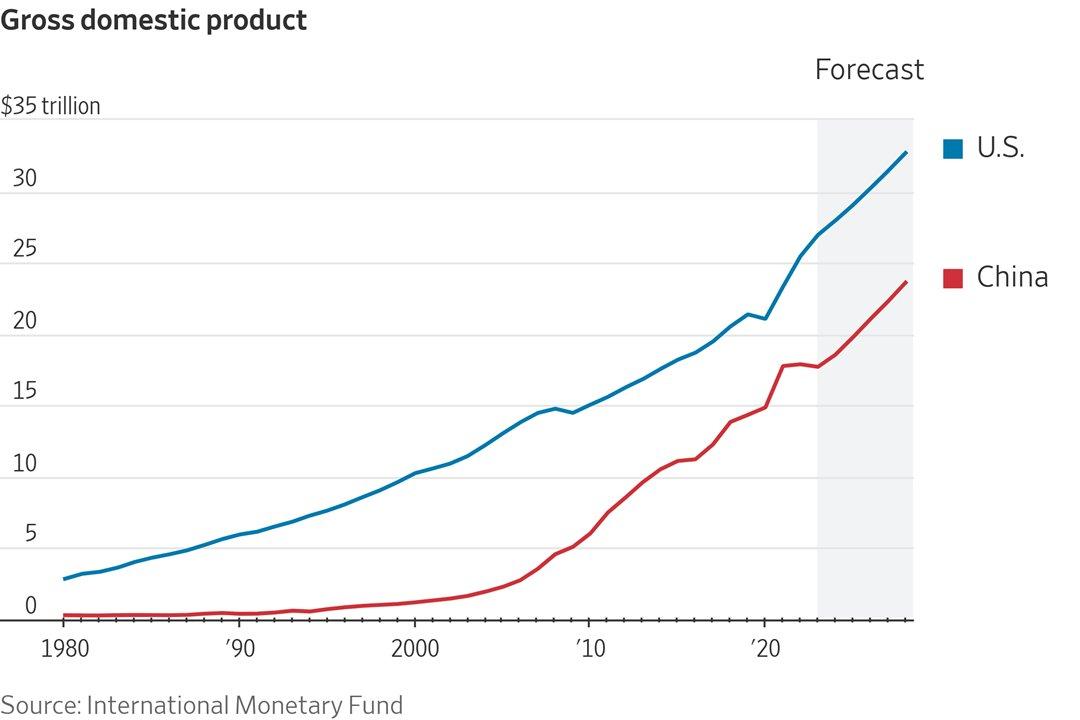

Economic growth and GDP aren’t the only things that matter in society, of course, but they do matter—not only for our own living standards but for geopolitical influence. As we discussed in May regarding China and its own demographic challenges, new research shows that the main drivers of a nation’s global economic power (as measured by its share of world GDP) are productivity growth and population (demographic change). Thus, staving off demographic decline and boosting growth are in our economic and foreign policy interests.

And there are other reasons for concern beyond simply growth. Research shows that older societies are less innovative and dynamic, as older people are—quite reasonably!—less likely to move or take risks than are younger people who have less to lose or fewer occupational or geographic roots. Some of it is also just a numbers game: More workers means more chances that someone has a “Eureka!” moment. AEI’s Jim Pethokoukis summarized some of the relevant research back in 2021:

“Other things equal, a larger population means more researchers which in turns leads to more new ideas and to higher living standards,” explains Stanford University economist Charles Jones in his 2020 paper, “The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of a Declining Population.”

And not just that. Researchers have linked the long-term decline in the US startup rate to the long-term slowing in the growth rate of the US labor force, with the latter explaining as much as 70 percent of the former. And if “present trends in fertility and immigration continue, the startup rate will remain near its current levels,” write Fatih Karahan (New York Federal Reserve), Benjamin Pugsley (University of Notre Dame), and Ayşegül Şahin (University of Texas) in their 2019 paper, “Demographic Origins of the Startup Deficit.”

Likewise, the late Nobel laureate economist Gary Becker also saw the important linkage of fertility to productivity: “Low fertility reduces the rate of scientific and other innovations since innovations mainly come from younger individuals. Younger individuals are also generally more adaptable, which is why new industries, like high tech startups, generally attract younger workers who are not yet committed to older and declining industries.”

Other research finds similar things (e.g., “lower labor force growth reduces creative destruction, increases average firm size and raises market power”).

Older societies also require more resources—workers, relatives, robots, capital, whatever—dedicated to things that cater to those populations, like late-in-life caregiving. Such activities are fine and good and even noble, but they inevitably have an opportunity cost: Dedicating more resources to, say, building assisted care facilities or taking care of aging parents means dedicating fewer to other things that might (read: probably will) set the country on a more dynamic, innovative, high-growth trajectory.

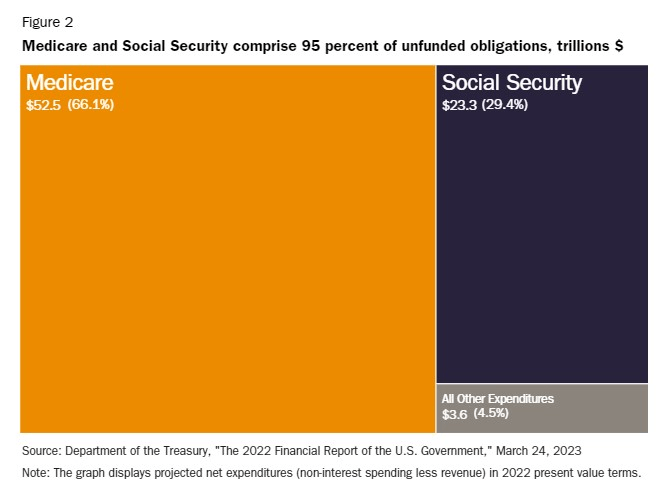

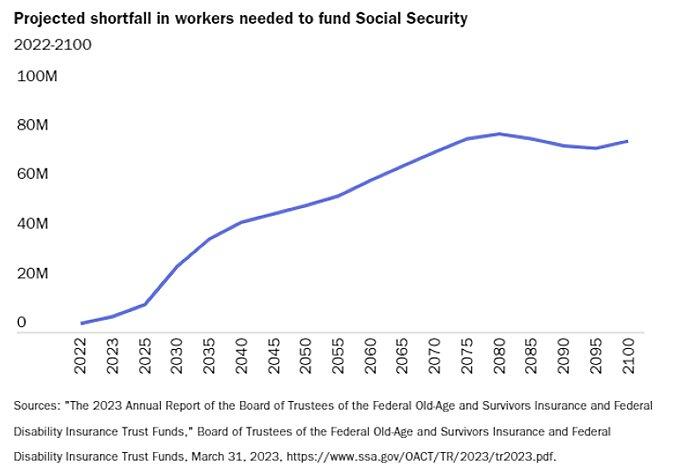

Finally, an aging society inevitably affects its government’s fiscal situation. Most notably, it contributes greatly to our entitlement-driven debt debacle. “Over the next 75 years,” my Cato colleague Romina Boccia recently explained, “Medicare and Social Security funding shortfalls comprise 95 percent of the total unfunded obligation.”

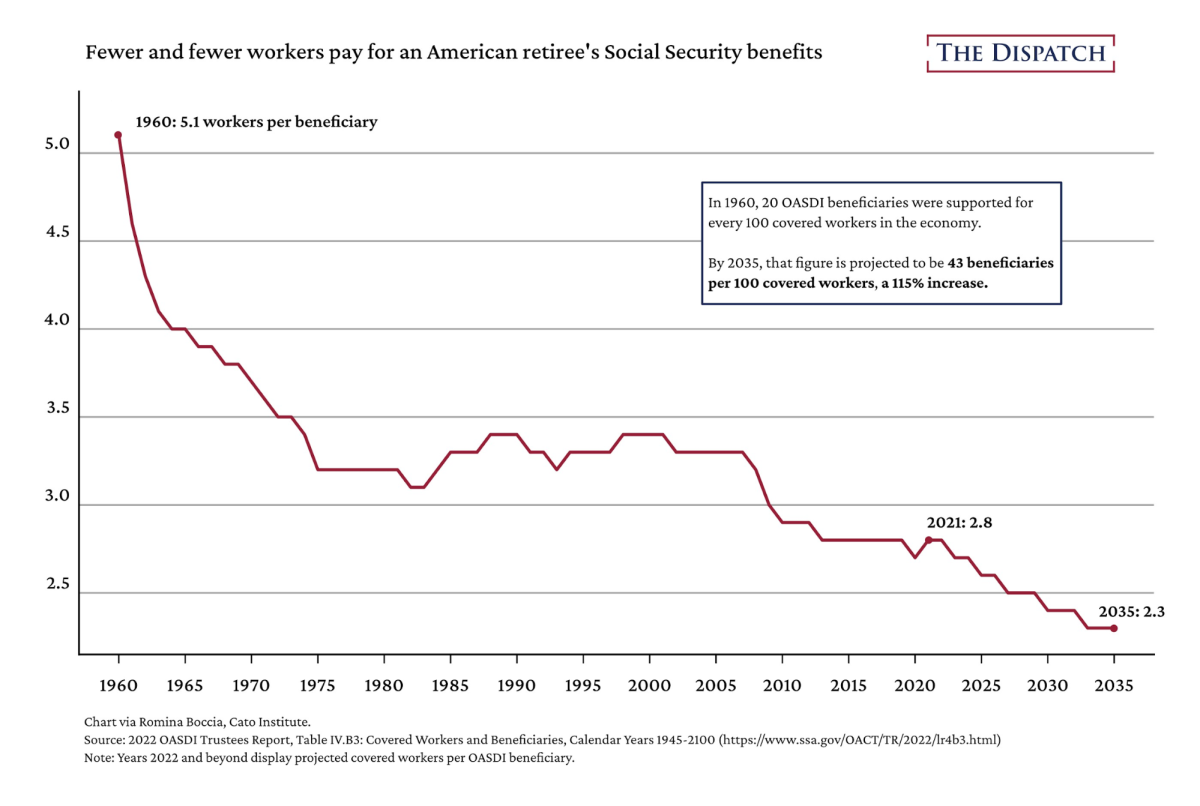

As Boccia has explained, some of this shortfall stems from how the system is designed (especially the increasingly generous benefits paid out to already wealthy people). But most of it is just simple demographic math: In 1960, for example, there were more than five workers paying for each Social Security beneficiary; today, however, it’s just 2.7, and it’ll be 2.4 in 2034.

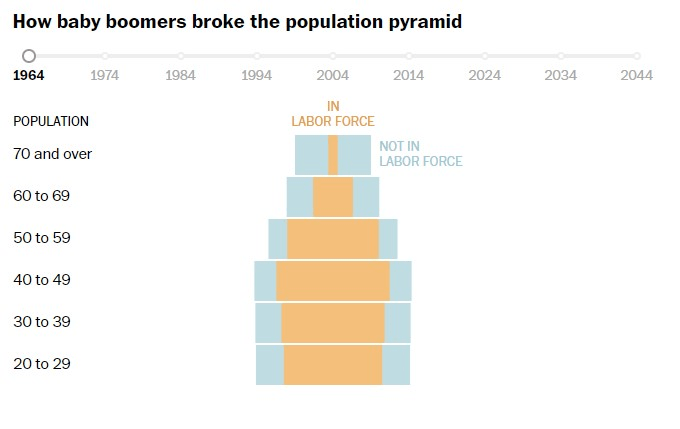

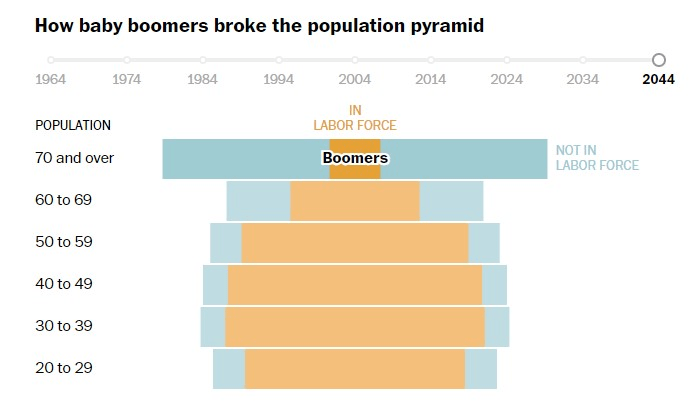

As helpfully demonstrated in this great Washington Post infographic, most of this decline has been caused by the abnormally large baby boom generation moving from the U.S. workforce into retirement and by subsequent, smaller generations of natives and immigrants being unable to fill the workforce gaps that those retirees left behind:

Thus, the Social Security trustees have recently estimated that the system will need an additional 35 million workers to continue to provide full benefits in the 2030s—a worker shortfall that’ll only keep growing in subsequent decades (until about 2080):

Demographics also raise other fiscal issues, including at the state level. One 2013 study projected that the aging U.S. population between 2011 to 2030 would result in lower labor force participation, and thus reduce per capita income tax and sales tax revenue, in almost every state—an annual loss totaling billions of dollars.

In sum, whether you care about America’s economic growth and dynamism, its geopolitical influence, or its social safety net, you care about American demographics.

But It’s Not All Demographic Doom and Gloom

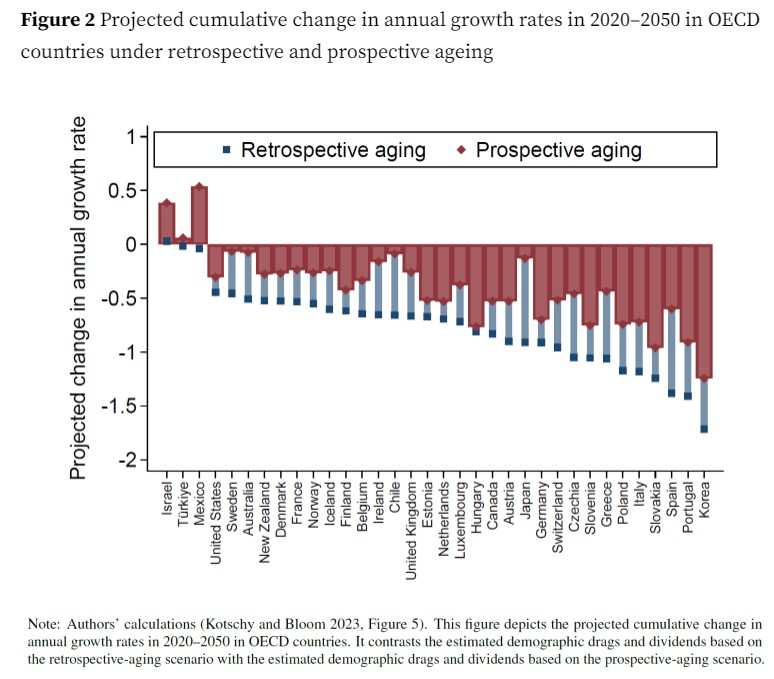

While the aging U.S. population and workforce will undoubtedly pressure the economy and government finances, it’s an open question as to just how serious that pressure will be. As new research from Harvard’s Rainer Kotschy and David Bloom shows, past examinations of an aging population’s drag on economic growth may have been overstated. That’s because they failed to consider that although we’re getting older on average, we’re also living longer and—thanks to better health, new technologies, and more “age-friendly” jobs—working later life. As they put it:

The conventional measure of working age used to answer [demographic] questions classifies old age the same for every generation. This retrospective approach focuses entirely on chronological age and therefore ignores advancements in functional capacity in terms of mortality, disability, strength, and cognition wrought by healthy ageing. However, a 65-year-old in 1973 can differ substantially from a 65-year-old in 2023. For example, life expectancy at age 65 in the US rose from 15 to 19 years between 1970 and 2020 and is projected to reach 23 years by 2050 (United Nations 2022). Therefore, categorising those aged 65 as old—which, in effect, means ‘too old to work’—is significantly undercounting the labour potential, an oversight that will only be exacerbated in the future.

To correct for this oversight, Kotschy and Bloom examine not only a population’s chronological age (years lived since birth) but also its remaining years of working life based on prevailing health and other trends. They make two important findings: First, OECD countries—including the United States—have a “younger” working population when examined from a prospective rather than retrospective (chronological) angle. Second, and relatedly, most developed economies could experience a smaller drag on economic growth from population aging thanks to older workers’ having more capacity to keep working. In the United States, the age-induced economic slowdown between now and 2050 goes from 0.45 percentage points per year (retrospective) to 0.30 percentage points (prospective). In some places like Sweden and Australia, the drag almost disappears entirely:

To be clear, these results still show that population aging in the United States and most other places will have significant economic downsides. And, as we’ve discussed regarding our modern Superabundance, humans are great for lots of economic and non-economic reasons. But at least some of the problems associated with our increasingly older population are probably “less dire” (in Kotschy and Bloom’s words) than many common estimates claim. As they put it, the “demographic drag” in most developed economies is “inevitable,” but its size and scope aren’t, thanks to many open questions about how governments, markets, and individuals will adapt to demographic changes in the coming decades:

How will society counteract these effects with investments in education, technological progress, and initiatives to promote healthy ageing that could result in increased functional capacity (that may lead more older individuals to remain in the labour market or to contribute via valuable non-market activities)? How will increased automation, capital deepening, and the uncertainty of data extrapolations inherent to these estimates complicate economic projections?

Thus, we should still be concerned about the aging U.S. population for lots of reasons, but—as is so often the case—our economy’s ability to adapt (through automation or AI or anti-aging medicines or whatever) cautions against full-blown demographic doomerism.

So, What Can We Do?

That dose of optimism, however, doesn’t direct policymakers to do nothing in response to the remaining demographic pressures we’ll face, especially where doing so brings other benefits too. This means not only continuing light-touch regulation on AI, self-driving cars, caretaker robots, and other technologies that can boost productivity or ease various resource constraints, but also embracing policies that can slow or even reverse future U.S. population declines. (Robots don’t pay taxes or buy stuff, after all.)

In this regard, there are two (not mutually exclusive) options: having more babies or admitting more immigrants. The former sounds (and would be) great, as babies are awesome, but—as my colleague Vanessa Calder explains in a recent paper—various “pro-natalist” policies around the world haven’t been very effective in boosting fertility. Instead, “Once a country’s birthrate has fallen below the replacement rate, recent history indicates that it tends to remain there: in recent years, no examples show a developed country rising back to, or above, replacement level and sustaining that rate after dipping below that threshold, although there exist precedents for temporary reversals.”

Meanwhile, Calder shows that government policies expressly intended to boost fertility impose large fiscal costs yet rarely hit their targets, and projections for various U.S. proposals show much the same.

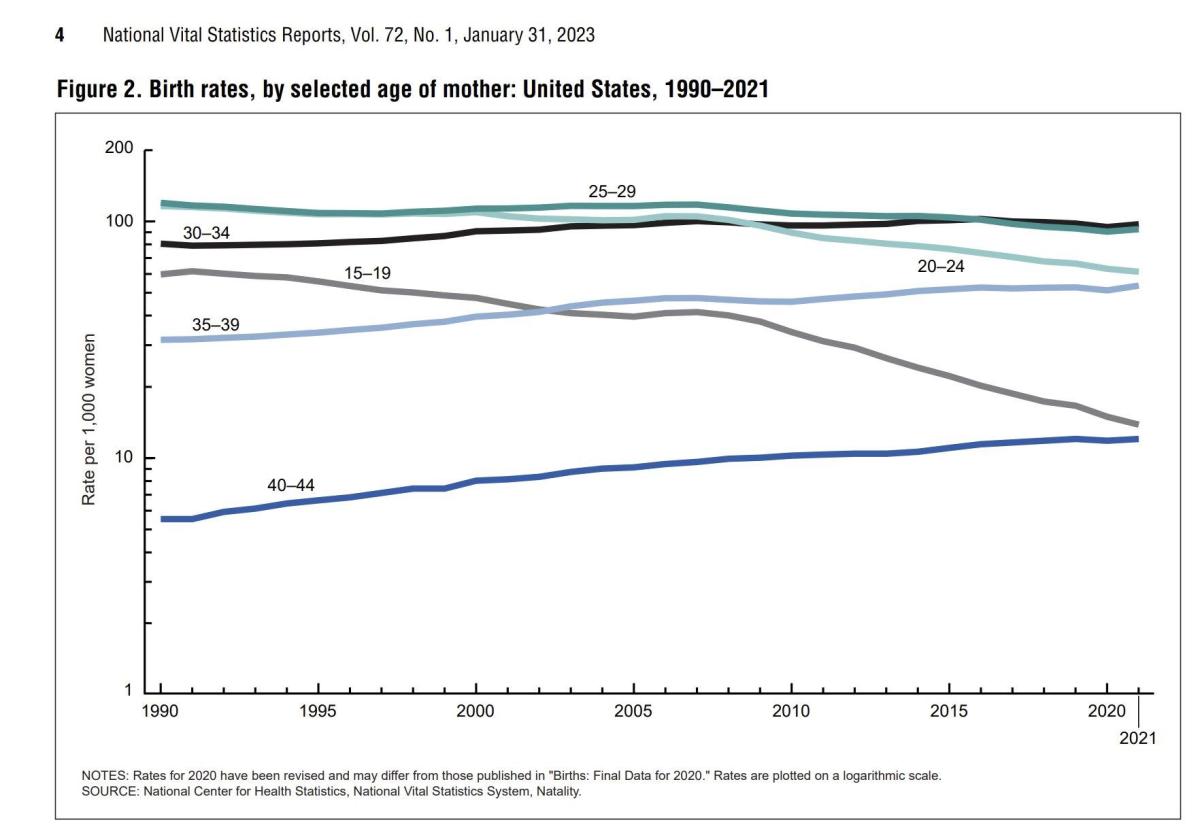

It’s also an open question as to whether we really want to reverse some of the recent declines in U.S. fertility (baby awesomeness notwithstanding). As Calder and economist Jeremy Horpedahl just tweeted, “one of the more inconvenient truths” about declining U.S. fertility since the 1990s is that it’s been in large part driven by a drop in the teen birth rate—something mostly to be celebrated:

Based on these figures, Horpedahl calculates that falling teen births accounted for about half of the total annual decline in U.S. fertility since 2005. We probably don’t want to encourage a strong rebound in those numbers.

Of course, this still means that adult Americans are having fewer babies, as increases in births among women ages 35+ have offset some, but not all, of the decline in births among women in their 20s. And here, Calder shows, there are a load of good reforms that U.S. governments could enact to make things easier on prospective or current parents and avoid the fiscal costs and unintended consequences of new parental subsidies (which can actually increase prices without concurrent supply-side reforms).

This includes reforming regulations or lowering taxes/tariffs that raise the prices of the things parents disproportionately need and consume—housing, food, clothing, child care, etc.—while also enacting new education, flex/remote work, health care, safety, and other policies that would better address current and prospective parents’ diverse needs and simply make parenting easier in America than it currently (and needlessly) is. Capitolism readers will undoubtedly be aware of many of these policy reforms already, but you can check out Calder’s paper for more.

Will any of this work in boosting fertility? Well, as AEI’s Scott Winship has shown in rigorous detail, making it cheaper to raise a child might not translate to more children because 1) it appears that American women today are no less successful than past generations in terms of having their desired number of children; 2) fewer than half of women today say they failed to achieve the fertility level they wanted as young adults (itself a datapoint rife with challenges, as expectations can and do change as one ages); and 3) the “main barrier to achieving desired fertility levels is the delay and decline of marriage,” something cheaper baby formula or childcare or whatever can’t fix. Pervasive economic doomerism regarding the cost of raising a family in America, moreover, is mostly misguided—something we’ll discuss more at length in a few weeks.

Nevertheless, the horizontal, free market reforms that Calder, I, and many others have proposed would have broad societal benefits—more abundant housing, lower food prices, etc.—and raise few downsides, unlike targeted parental subsidies. Potentially boosting fertility would be icing on the cake.

Immigrants—They (Could) Get the Job Done

Regardless of where one stands on the fertility debate, any boost in U.S. fertility today would take decades to produce labor market, fiscal, or related economic results. Last I checked, it takes a minimum of ~19 years from being conceived to becoming a full-time, taxpaying member of the workforce (sometimes, as many parents can attest, much longer!), but the United States’ demographic pressures are happening right now.

Immigration, on the other hand, can mitigate some of these pressures immediately—and it already is. In 2022, “international migration accounted for 80 percent of the meager 0.4 percent population growth” in the United States. And new census data show how changes to U.S. immigration policy could play a major role in staving off the future contraction of the U.S. population—or, depressingly, in fueling it.

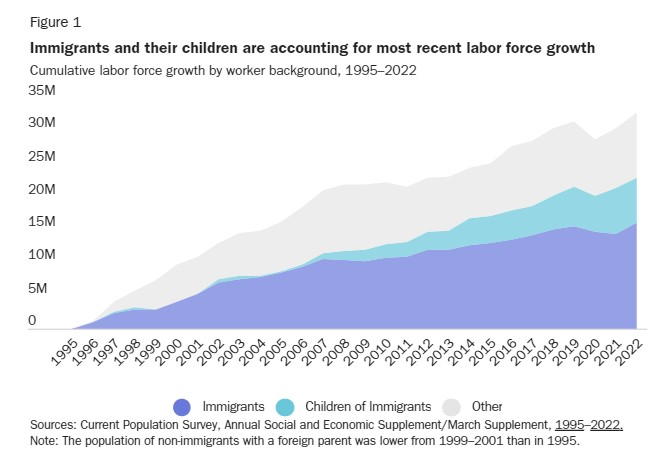

My Cato colleague David Bier expanded on this issue in his recent Senate testimony, showing all the ways that increased immigration could improve U.S. demographics—and thus economic growth, innovation and entrepreneurship, and the workforce. Indeed, immigrants have long been a driver of expanding U.S. labor force growth: Between 1995 and 2022, the workforce increased by almost 33 million people, and about 70 percent of that growth came from immigrants (16.1 million immigrant workers and 6.7 million children of immigrants), while just 9.9 million were U.S.-born citizens without a foreign‐born parent.

Immigrants are also essential for fields like construction, elder care, or child care where job openings remain well above pre-pandemic levels and future demand is high (in some cases because of demographics). Without increasing immigration, Bier notes, these and other critical industries—and their consumers—will suffer. Here’s one stark example:

With 1 million new jobs, home health aides are projected to see the largest increase in employment of any single occupational category. These aides are critical to provide care for seniors, and they allow many older workers to keep working while caring for an ailing spouse. But without the workers to fill them, the growth in aides may not happen. America has even seen declines in employment in critical areas of elder care, despite record demand. Shockingly, for instance, the number of employees in skilled nursing care facilities has declined from 1.7 million to 1.4 million from 2011 to 2023.

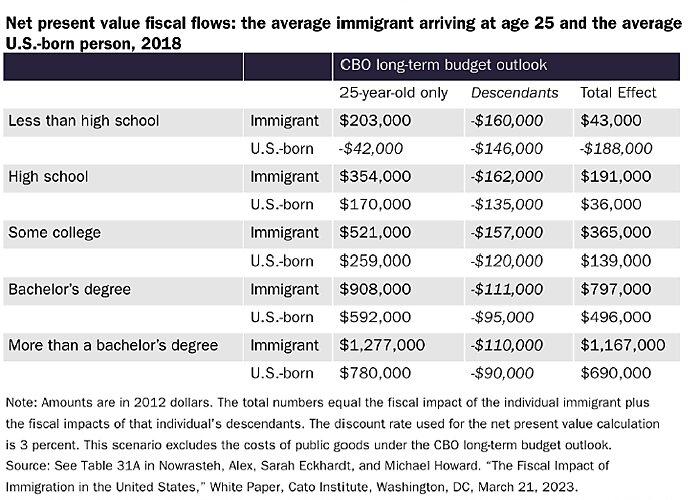

Finally, and contrary to what you might hear, immigrants are generally a net boost to, not drain on, government coffers: “immigrants generate, in inflation‐adjusted terms, nearly $1 trillion in state, local, and federal taxes, which is almost $300 billion more than they receive in government benefits, including cash assistance, entitlements, and public education. In the long‐term, the present value of all the taxes generated minus all the benefits received for an immigrant arriving at age 25 is positive for all education levels, including high school dropouts.”

As more American baby boomers retire and die, just maintaining a stable labor force and population will respectively require increasing immigration, while actually exceeding these targets will require even more. Per the Census Bureau’s new calculations, in fact, the base case population projection—which shows the U.S. population leveling off in a few decades—sees the United States’ net international migration position (foreign entrants minus native exits) increase by almost 100,000 per year, from 853,000 to more than 950,000, for most of the century. That net migration position would need to almost double over the next decade—to an average of more than 1,560,000 net additions per year!—to meet the Census’ “high immigration” scenario that keeps the U.S. population growing steadily. Even later in the century, the base-case / high immigration differential is more than 500,000 people per year. That’s a lot of extra people.

So, sure, let’s enact smart policies that’d make it easier for American parents to have and raise kids, but a serious response to continued U.S. demographic pressures will inevitably require more immigrants too—and that, as Bier documents (and as we’ve discussed at length), means fixing the United States’ byzantine and restrictive immigration laws.

And there, unfortunately, lies another reason for pessimism.

Chart(s) of the Week

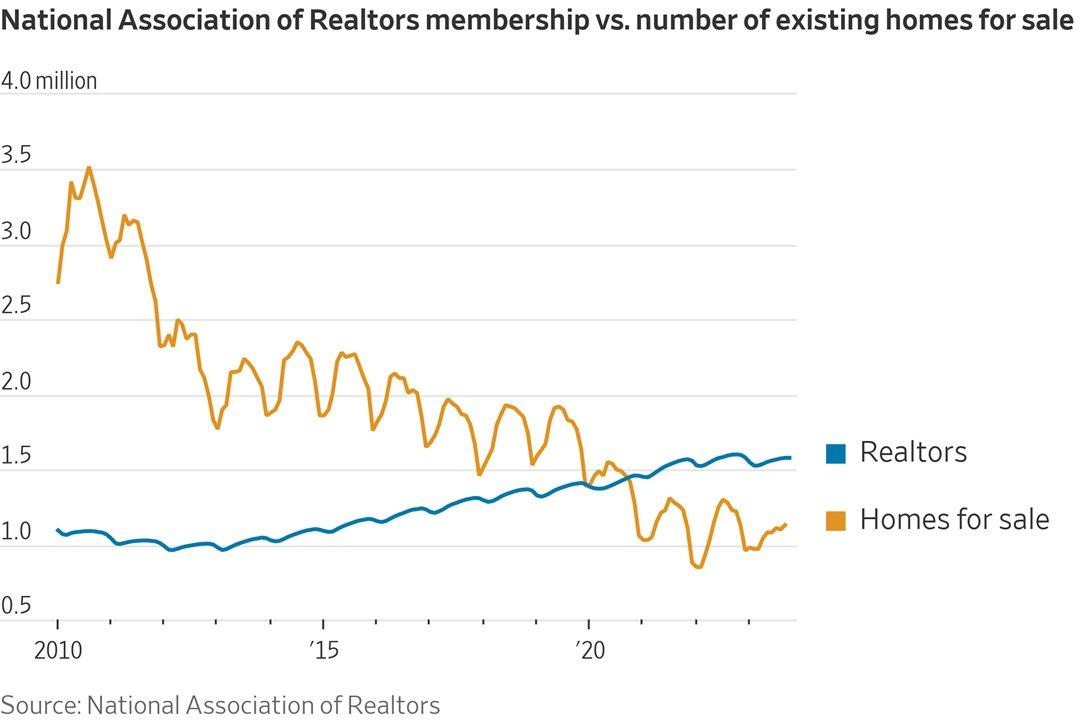

Realtor glut:

The Links

More new Defending Globalization content: cryptocurrency and Bangladesh and a video chat with economist Deirdre McCloskey

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.