Dear Capitolisters,

Yesterday, Cato published a new paper from my colleague Clark Packard and me proposing a better, saner approach to U.S. policy toward China. We warn that current U.S. policy has thus far proven not only ineffective but also incoherent and even counterproductive against the very real economic and geopolitical challenges that today’s China presents. Capitolism’s most diligent readers (which of course you all are) will recognize a lot in the paper, especially on the foolishness of current U.S. tariff and trade agreement policy—toward China, U.S. allies in Europe and elsewhere, and (most insanely) non-China alternatives like Vietnam. My most recent newsletter, in fact, explained how tariffs, U.S. non-involvement in trade agreements, and other moves have nudged developing countries like Vietnam and Malaysia further into China’s economic orbit. And, of course, I’ve spilled a lot of virtual ink detailing how the Trump/Biden tariffs have undermined American companies’ competitiveness—increasing production costs, discouraging investment, etc—while doing little (if anything) to hobble China or persuade Beijing to change course. So, don’t worry, I won’t be banging those drums again this week.

Another, non-trade area, on the other hand, deserves emphasis when it comes to U.S.-China policy—immigration. And on this score, the United States is failing pretty miserably.

First, Let’s Be Realistic

Before we get to that, however, it’s important to emphasize that U.S. trade and foreign policy discussions frequently suffer from an almost comical lack of humility about the extent to which Washington’s actions can and do affect the geopolitical and economic decisions of foreign nations—especially big ones. We often hear, for example, how U.S. trade policy was single-handedly responsible for China’s rise, while anyone with a lick of knowledge about the issue will tell you that most of China’s economic and trade prowess today is owed to its own market-oriented internal reforms (privatization, market opening, etc.), not increased access to the U.S. market in the 1990s and 2000s. The latter probably accelerated Chinese economic growth a bit, but China was rising regardless.

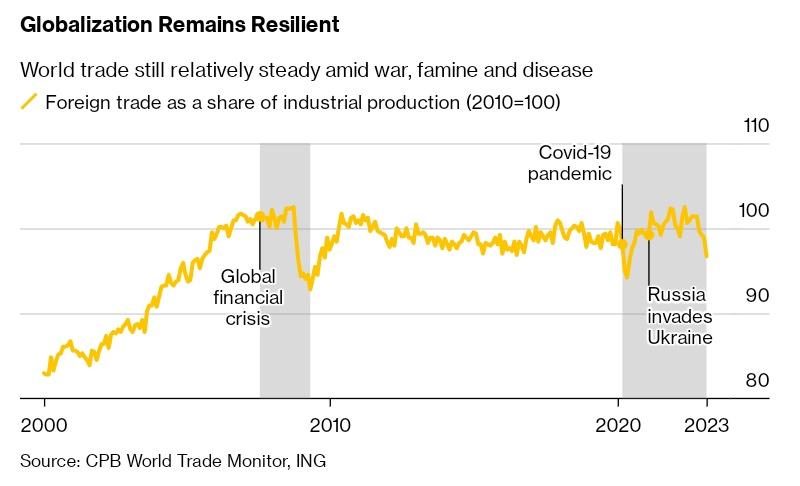

Furthermore, Americans tend to forget or ignore that foreign countries are sovereign entities run by humans that have their own, mainly domestic political motivations and interests—ones that often (if not usually) outweigh whatever carrots or sticks the United States is dangling. Thus 1980s U.S. tariffs targeting “unfair trade” policies abroad were rarely (only 17 percent of the time) able to convince the offending foreign countries to abandon their protectionism, and instead often generated tit-for-tat retaliation by governments that couldn’t be seen by their citizens as being bullied by the big, bad U.S. of A. Negotiating successes were more common, but still occurred in less than 50 percent of all cases—and mainly when the targeted country was dependent on the U.S. market for its exports (something that’s less likely today due to the diversity of global economic growth). Recent experience with Trump’s China tariffs and his laughable “Phase One” deal reinforces these conclusions.

It’s thus widely accepted—until recently, at least!—that smart geopolitical strategy 1) seeks to avoid direct, vocal, and widescale confrontation; 2) chooses instead some quiet combination of targeted direct actions (tariffs, sanctions, litigation, etc.), economic carrots (trade deals, foreign aid, etc.), and bilateral or multilateral talks that seek to persuade foreign governments to do stuff that’s arguably in their own political or economic interests; and 3) supplements that stuff with improvements to U.S. economic policy that can advance national interests regardless of what other nations do.

The United States isn’t doing so hot on any of the three right now. But it’s the last one—and on immigration policy in particular—where things may be most disappointing.

A Superpower We Don’t Use Nearly Enough

It’s frequently said that immigration is America’s superpower: Among the world’s most powerful nations, we’ve long been unique in our ability to attract and retain smart, hard-working people. And the economic and geopolitical results have been spectacular.

Consider a few examples:

First, there are the myriad and undeniable benefits that immigrants have had on U.S. innovation. As Caleb Watney explained in 2021, three waves of U.S. foreign talent recruitment between 1930 and 1960—countering the Nazis and then the Soviets (including “Operation Paperclip”)—turned the “intellectual backwater” United States into a technological and scientific powerhouse and a magnet for the world’s smartest people:

The net effect of these three waves has been America’s consistent domination of international science and technology. Using the Nobel Prize in Physics as a rough proxy, American scientists were involved in only three of the thirty prizes awarded between 1901 to 1933. From 1934 to 2020, Americans have been involved in roughly two thirds. And an enormous share of American Nobel laureates have been either first- or second-generation immigrants from these three waves.

…

We ceased needing to actively recruit immigrant inventors because they naturally wanted to come to the global center for talented scientists and engineers. William Kerr, in his book The Gift of Global Talent, documents that between 2000 and 2010, more immigrant inventors came to the United States than to the rest of the world combined. We built it, and they came.

Today, immigrants are about twice as likely to be granted patents as nonimmigrants, because they disproportionately have degrees in science and engineering.

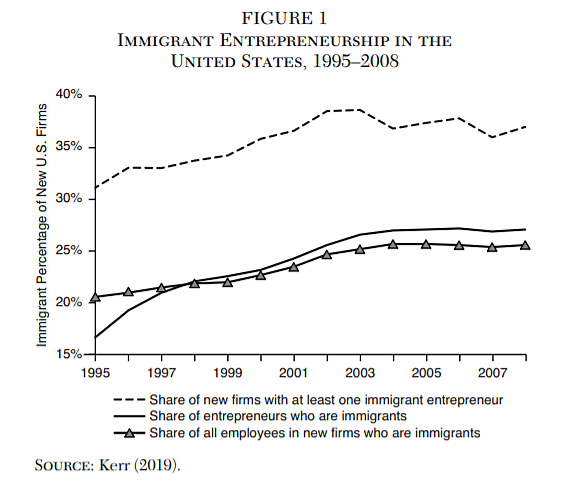

Research also shows that immigrants in the United States are highly entrepreneurial—more so than nonimmigrants:

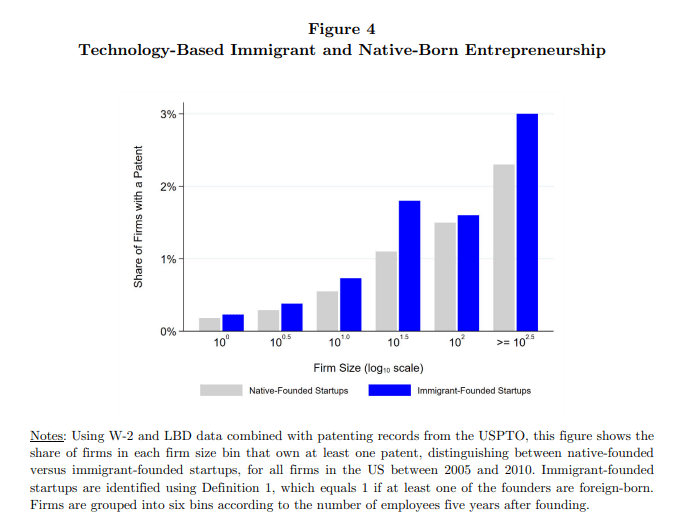

These new firms not only employ lots of Americans, they’re also innovative. According to one recent study, for example, “Firms with an immigrant founder are 35% more likely to have a patent than firms with no immigrant founders. Studying firms by size group, those founded by immigrants are more likely to have patents at all sizes and especially at larger sizes.” It’s no surprise, then, that immigrants helped found some of America’s most innovative firms, including Google, Uber, Qualcomm, Tesla, eBay, Yahoo, and Pfizer.

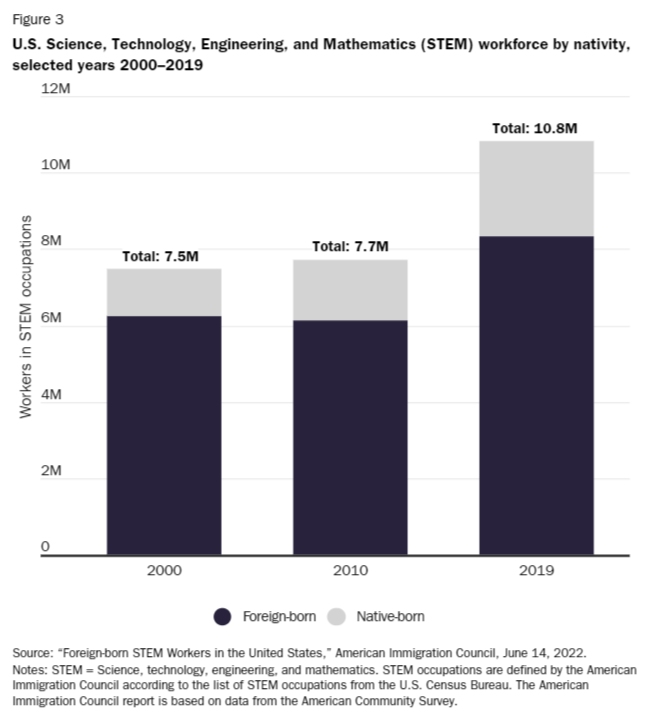

But immigrants aren’t just founding U.S. tech companies; they’re staffing them too. As economist Kimberly Clausing notes in her recent book, for example, “As of 2014, 46 percent of Silicon Valley’s workforce was foreign‐born. The share is even larger for workers between the ages of 25 and 44, and it rises to a whopping 74 percent of workers hired for their math and computer expertise in that age bracket.” Between 2000 and 2019, the U.S. foreign‐born STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) workforce increased substantially:

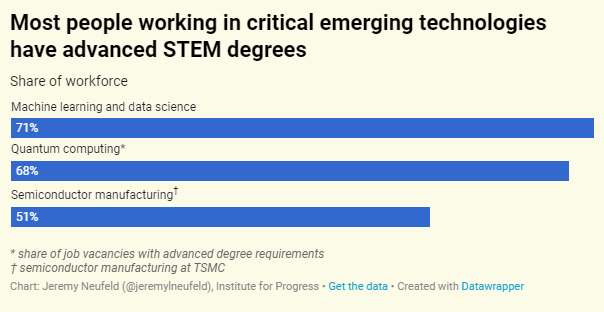

Immigrants are especially important for domestic companies working in emerging technologies that U.S. government officials have themselves deemed critical. The U.S. semiconductor industry—which still leads the world in many key areas—is highly dependent on STEM immigration. The same goes for artificial intelligence, with economists finding that foreign‐born workers account for most of the job growth in AI‐related occupations since 2000, and that U.S. immigration restrictions deter AI development here and give China’s state-directed approach an advantage.

As GMU’s Alex Tabarrok noted in January, there are just so many high IQ workers in the world—and probably only about 164,000 in the United States (i.e., maybe enough to run the entire semiconductor industry, but little else). So if we want the United States to continue to lead the world in the Industries of the Future (or whatever), then it’s essential we welcome the world’s best and brightest from wherever they’re currently residing.

Second, immigrant workers provide benefits beyond the industries that employ them. Research shows, for example, that between 1990 and 2010, the “inflows of foreign STEM workers explain between 30% and 50% of the aggregate productivity growth” in the United States. Immigrant innovators have been found to complement (not supplant) native-born inventors, raising their productivity and innovation over time. For example, “[a] 1 percentage point rise in the share of immigrant college graduates in the population increases patents per capita by 9–18 percent.” Other research finds that immigrants boost a locality’s creative destruction and economic mobility—among firms and individuals.

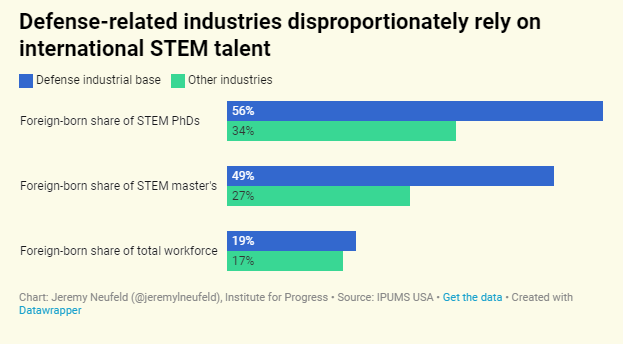

Immigrants are also critical to U.S. national defense, with foreign-born workers disproportionately represented throughout the defense industrial base.

That’s a big reason why, as The Dispatch’s Haley Byrd Wilt noted last year, a bipartisan group of former national security officials—including some from the Trump administration—publicly urged Congress to expand immigration as part of the CHIPS and Science Act. (Depressing spoiler: Those draft provisions were dropped.)

Just as importantly, if the United States doesn’t get its act together on immigration, innovative foreign workers and the companies that employ them won’t just say “aw shucks” and do nothing—they’ll move to more welcoming places like Canada and China. Indeed, past U.S. immigration restrictions have been found to encourage R&D-intensive companies to offshore operations to other countries that have or can get the workers they need—generating new jobs, new businesses, and new innovations in those places instead of the United States. We’ve seen similar effects in recent years:

Pushing smart people away from the United States and into China is a particularly dumb move, given that China has long struggled to retain or attract skilled workers and innovators.

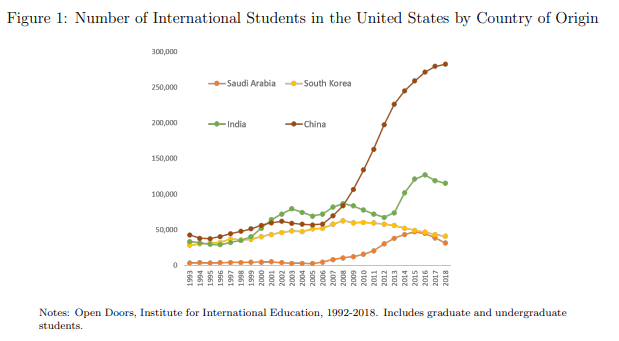

Third, immigrants boost U.S. colleges and universities, which have long been breeding grounds for innovation. Clausing reports, for example, that visa-holding students comprise a disproportionate share of graduate students in science, computer science, and engineering. Multiple studies also show that, contrary to myth, the vast majority (around 85 percent or more) of Chinese graduate students in STEM fields remain in the United States instead of running back to Beijing with their shiny new “American” education. (And, before you ask, they’re not all spies either.) In non-STEM fields, meanwhile, Chinese students have paid “full‐sticker price tuition payments” at smaller colleges and universities around the country, thus boosting those institutions, their American students, and their surrounding communities.

Those effects, along with longer term benefits for U.S. innovation, are consistent with past research on foreign students generally, not just those from China. They’re a win-win-win-win.

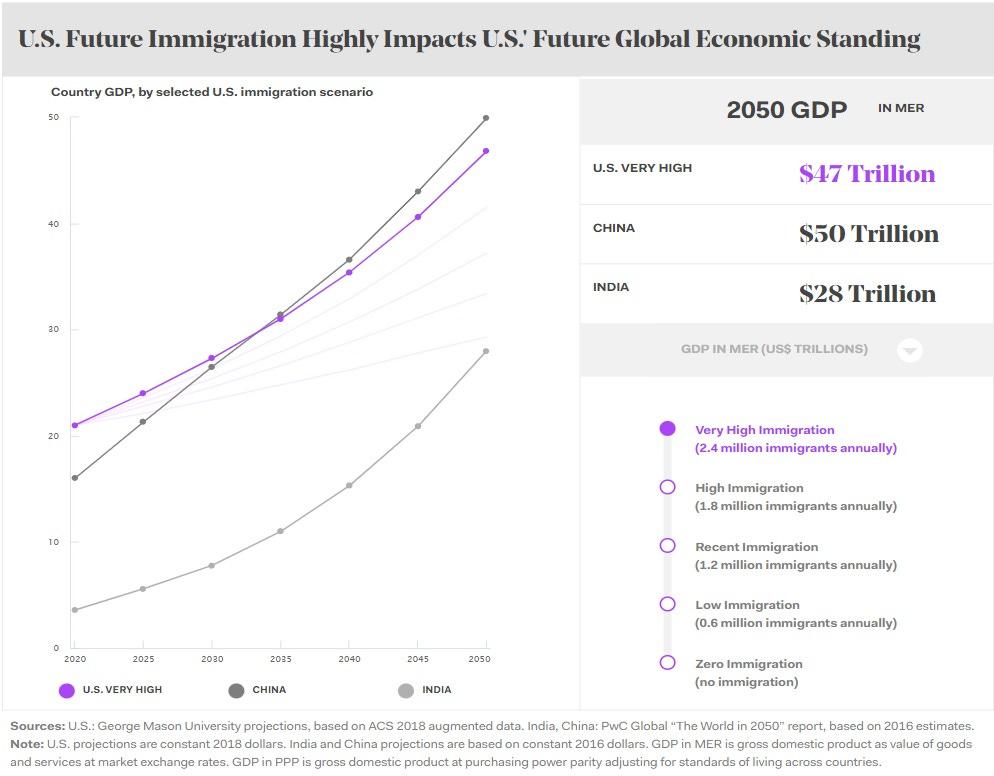

Finally, expanded immigration of all types would help the United States confront future demographic challenges—and press its advantage in a clear area of Chinese weakness. As AEI’s Jim Pethokoukis explained last year, new research shows that the main drivers of a nation’s global economic power (as measured by its share of world GDP) are productivity growth and population (demographic change). The United States faces some demographic headwinds, but:

The US has a unique ability to change that population prediction through immigration. According to immigration scenarios prepared by researchers at George Mason University in a study commissioned by FWD.us, projections show the US population would grow to nearly 500 million people by 2050 if US immigration levels were doubled. (As Matthew Yglesias notes in his book One Billion Americans, that many Americans only would get us the population density of France. It would get us one-half the population density of Germany.) But as other nations grow richer, there is far less incentive for their strivers to move to America. You can open your borders all you want, but people have to want to come. Pro-immigration reform should be top of mind for American policymakers.

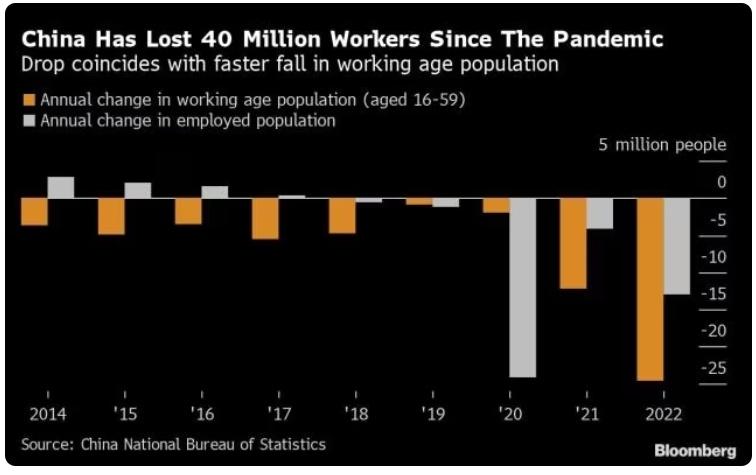

China, by contrast, has severe demographic challenges that, supercharged by COVID, are already affecting its workforce and economy:

And it only gets worse from here:

For the coming years and decades of the 21st century, the demographic transition in China will constitute a major constraint on the growth of Chinese power. A working-age population that peaked in 2011 at more than 900 million will have declined by nearly a quarter, to some 700 million, by mid-century. These workers will have to provide by then for nearly 500 million Chinese aged 60 and over, compared with 200 million today. America’s social security challenges seem like a policy picnic by comparison.

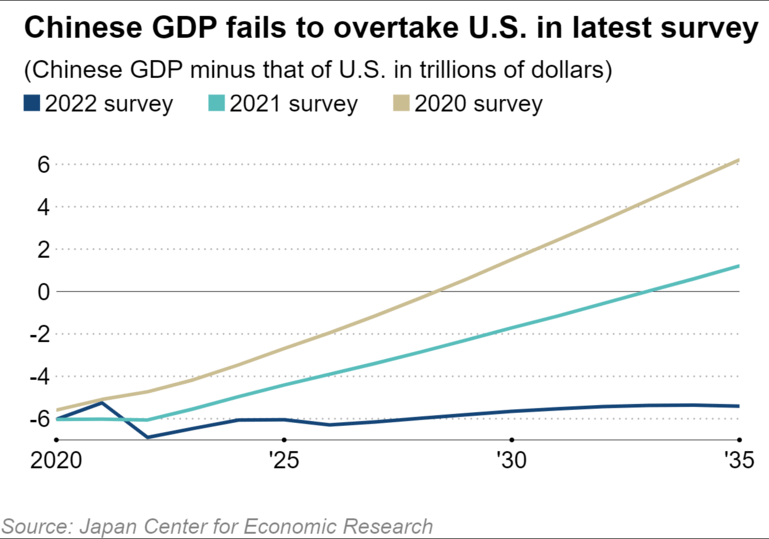

It’s now an open question as to whether China will ever overtake the United States in the GDP race, but there’s no good reason to take that chance.

Now, the Bad News …

Unfortunately, U.S. policymakers (and especially those most hawkish on China) haven’t embraced immigration liberalization to advance national economic and geopolitical objectives, and there are some troubling signs that we’re actually losing ground where it matters most—high-skilled immigrants.

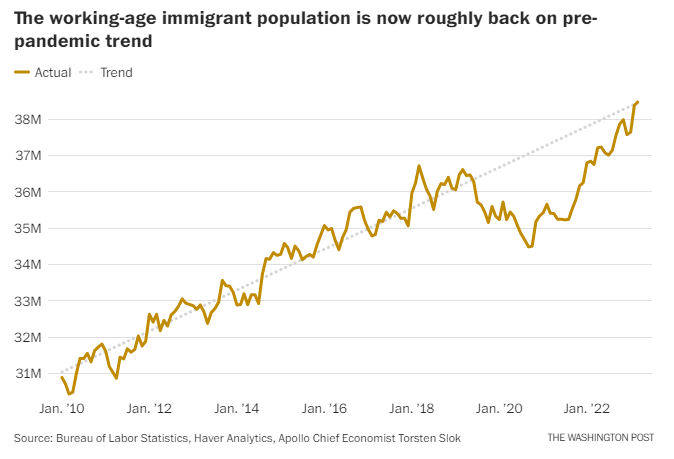

Thanks to Trump administration policy and the pandemic, legal immigration fell by about 50 percent between fiscal years 2016 and 2021. Immigration levels have recently returned to their pre‐pandemic levels, but the aging U.S. population and recent trends in the U.S. workforce (e.g. early retirements) demand an acceleration in immigration, not simply a return to the pre-pandemic trend.

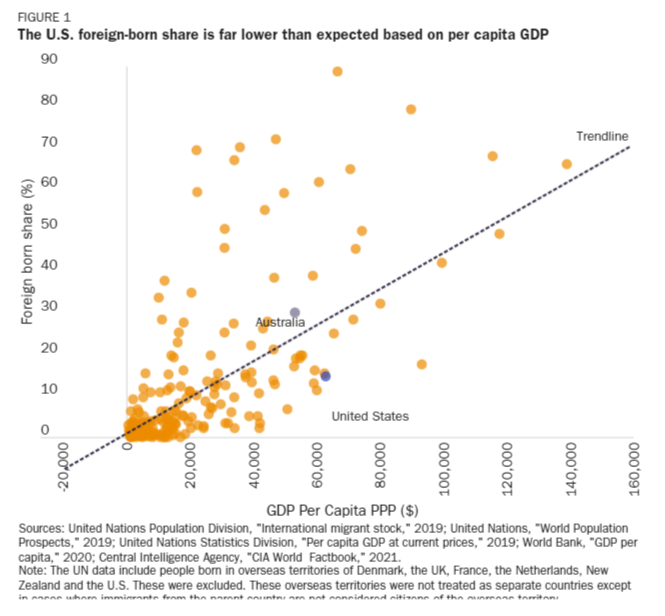

Indeed, if the United States simply had an average foreign-born population share for a country with its level of wealth, we’d have tens of millions more immigrants today:

That same research shows that, because many other rich countries (e.g. Canada) are wisely courting immigrants of all types to boost their economies, the United States’ share of foreign born population has fallen further down the global rankings. Another great nativist success! (Sigh.)

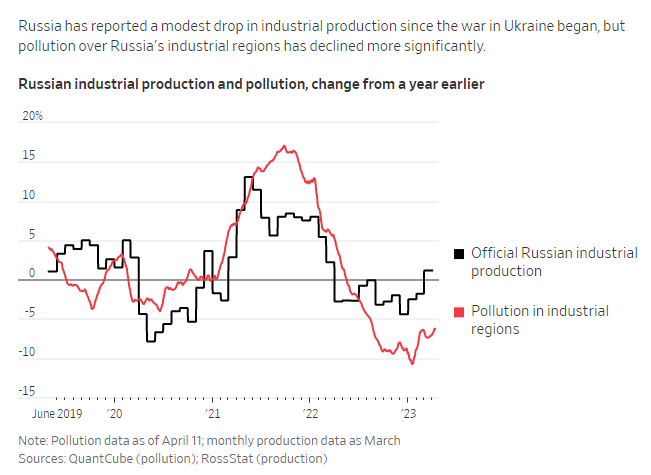

The news is even worse for skilled immigrants. The Wall Street Journal reported last year, for example, that Washington’s hostility toward Beijing is driving some of the top Chinese talent out of the United States. Recent research found that nearly 1,500 U.S.-trained Chinese engineers and scientists exchanged their U.S. academic or corporate affiliations for Chinese affiliations in 2021—a 20-plus percent increase from 2020. My Cato colleague David Bier recently crunched a broader dataset from the OECD and found a similar trend: “The United States lost published research scientists to other countries, while China gained more than 2,408 scientific authors.”

Bier then elaborates:

If an author who was previously affiliated with a different country publishes another article in a new country, the new country will be credited as receiving a new research scientist. The OECD credits more Chinese scientists returning to China for the sudden reversal in Chinese and American inflows.

This is a disturbing trend that started before the pandemic. In fact, it appears to coincide with the Trump administration’s “China Initiative”—more accurately titled the anti‐Chinese initiative. Launched in November 2018, the Department of Justice’s campaign was supposed to combat the overblown threat of intellectual property theft and espionage. In reality, it involved repeatedly intimidating institutions that employed scientists of Chinese heritage and attempting malicious failed prosecutions of scientists who worked with institutions in China. U.S. Attorney Andrew E. Lelling has even admitted that the initiative that he helped lead “created a climate of fear among researchers” and now says, “You don’t want people to be scared of collaboration.”

If Chinese scientists are afraid to work in the United States, that means that the United States will not benefit from their discoveries as much or as quickly as China will.

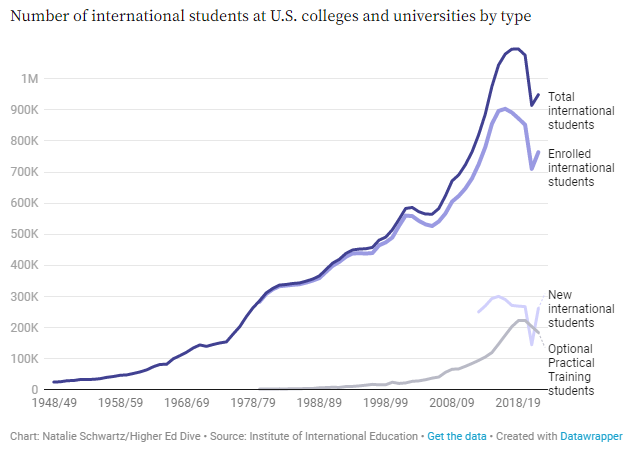

Other research from Bier found that the Trump administration oversaw an enrollment decline of tens of thousands of international students attending U.S. colleges and universities—a decline that COVID then supercharged. Fortunately, international student enrollment increased last year after various COVID restrictions mellowed, but total enrollment is still off recent trends:

And, of course, there are the visa backlogs and other procedural impediments to lawful, employment-based immigration, including for people with exceptional, in-demand skills. Consider this real-world example of these policies’ harms:

[Dr. Muhil] Ravichandran first legally came to the USA with her family when she was two years old, and settled permanently in the US by age nine. But when she became an adult she was no longer covered by her family’s legal status. Upon graduation from college, she was forced to turn to the vagaries of the green card system.

There are categories of green cards for those with advanced degrees that she could have qualified under, yet the wait period for those with Indian citizenship is measured in multiple years, decades, or even—as David Bier once calculated—more than a century. Recent college grads don’t have 151 years (!) to wait.

So she got a job at an oncology company—in a non‐research role—and her employer entered her name in the H-1B visa lottery, a highly competitive sponsored category. But last year there were ~484,000 applications for only 85,000 H-1B slots, meaning that Ravichandran’s chance of success was roughly 18%. Unfortunately, she was one of the 82% who was rejected.

And because of that rejection, she has already lost her job. She could have to move out of the US and try to apply again in the future. And if she applied under another category, like an EB-3 green card, she might make it back in 17 years give or take. But at that point, she may have put down roots in another, more serious country that isn’t so determined to shoot itself in the foot. She could stop applying altogether and the US would be worse off as a result.

Summing It All Up

While there are, I think, plenty of reasons to remain calm about the long-term threat that China poses to the United States and the world, that doesn’t mean that today’s China doesn’t raise real risks. But Washington’s current approach imposes a lot of domestic pain for very little gain, while leaving our broken immigration system essentially untouched.

That makes no sense. Immigration is good for U.S. innovation, entrepreneurship, national security, and demographics—and it has all sorts of positive “spillovers” for native-born Americans and the economy more broadly. It might even help—as Operation Paperclip and other U.S. efforts did decades ago—deprive authoritarian baddies abroad of the brains they’d need to fulfill their global ambitions. (Indeed, CCP officials have long tried, and failed, to keep smart locals home, and have famously complained, “The number of top talents lost in China ranks first in the world.”) It is—pardon the pun—a no-brainer policy, especially given that current U.S. policy leaves so much room for improvement, and that there are so many obvious reforms to be had here.

Immigration is our superpower. It’s time we used it.

Chart of the Week

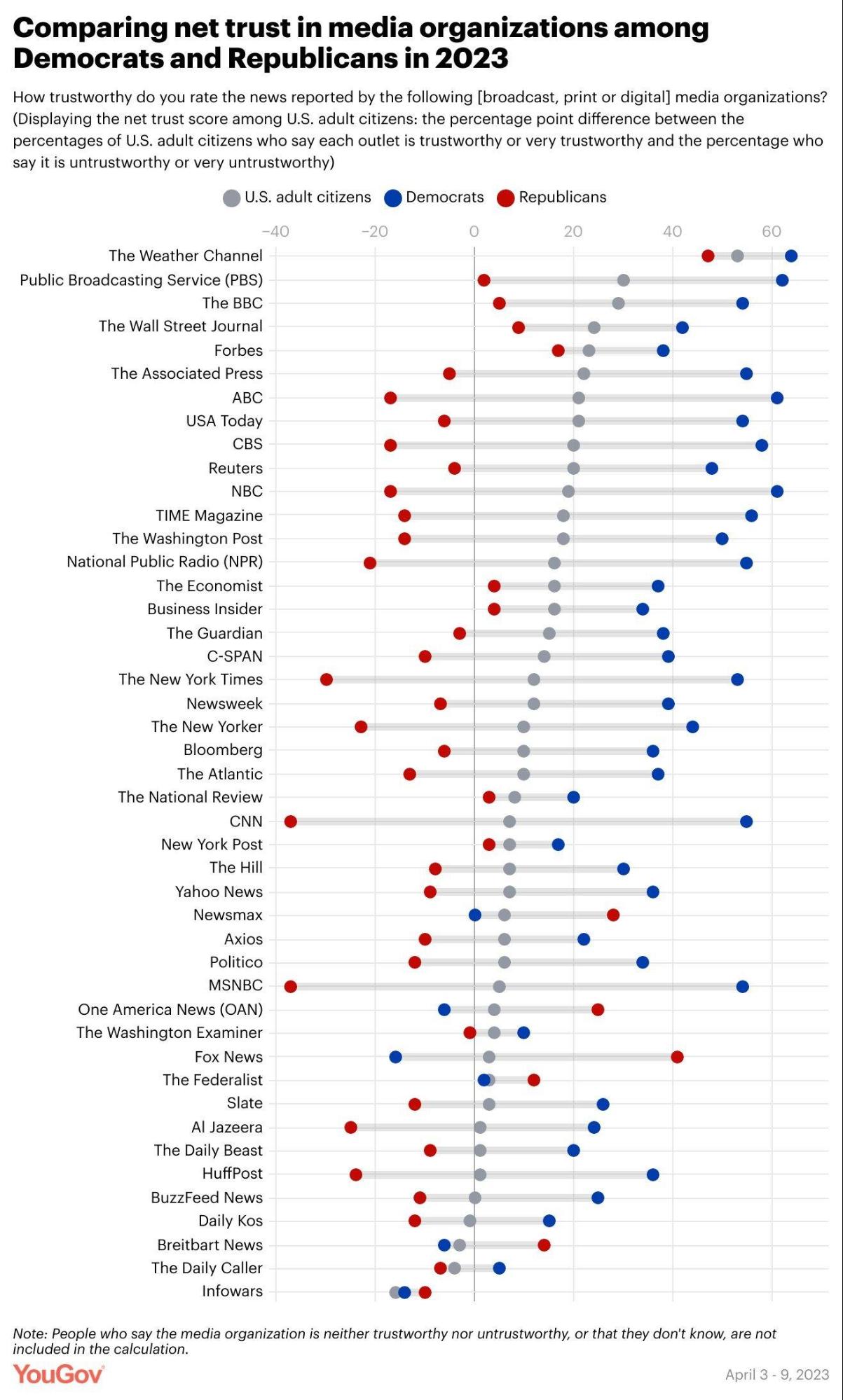

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.