Dear Capitolisters,

In last week’s State of the Union address, President Joe Biden gave what’s unfortunately become the standard laundry list of political promises and plans. But buried in his (very long!) speech was the following—and frankly silly—proposal to fight U.S. inflation by locating more production in the United States:

I have a better plan to fight inflation. Lower your costs, not your wages. Make more cars and semiconductors in America. More infrastructure and innovation in America. More goods moving faster and cheaper in America. More jobs where you can earn a good living in America. And, instead of relying on foreign supply chains—let’s make it in America.

Biden’s message might make sense politically: According to various reports, for example, a plan to drive down prices via “supply chain repatriation” polls well (far better, in fact, than the Democrats’ other big inflation-fighting plan, cracking down on corporate greed). So I guess it’s got that going for it, which is nice. Substantively, however, the plan is nonsense and would probably make things worse, not better, for the United States in the long run.

So that—sigh—is what we’ll discuss today.

Supply Chains Lower Costs, while ‘Localization’ Raises Them

Even granting Biden’s (questionable) premise that targeted, “microeconomic” policy reforms could significantly reduce the current inflationary pressures, the core flaw in his big reshoring plan is that global supply chains (aka global value chains or “GVCs”) tend to reduce prices, not raise them—especially when compared to wholly nationalized production (autarky). Indeed, that’s pretty much the whole point: The proliferation of GVCs and trade in manufacturing inputs (“intermediate goods”) was driven primarily by multinational manufacturers’ desire to leverage specialization and comparative advantage across multiple countries (not to mention revolutions in containerized shipping and information technology) to provide cost-conscious customers with the highest-value product at the lowest possible price. A recent Congressional Research Service report summarizes this well (emphasis mine):

The United States, in particular, was a driving force in breaking down trade and investment barriers across the globe and constructing the open and rules-based global trading system that has enabled GVCs to proliferate. While some workers and producers have experienced a disproportionate share of the short-term adjustment costs (e.g., through increased global competition or job losses) associated with the growth of GVCs, the net payoff to the United States and the global economy from GVC participation is estimated to be substantial. For example, stronger linkages to the global economy force U.S. industries and firms to focus on areas in which they have a comparative advantage, provide them with export and import opportunities, enable them to realize economies of scale, and encourage knowledge sharing and innovation. In addition, households have been able to enjoy lower product prices and a broader variety of goods and services—some of which may not be produced domestically.

GVCs also support a broad range of widely dispersed service-sector jobs in such areas as transportation, sales, finance, marketing, insurance, law, and accounting. Over the years, studies have shown that GVCs can boost growth, create better and higher paying jobs, and reduce poverty, especially when appropriate environmental, social, and governance policies are in place. According to one analysis, trade-dependent jobs in the United States increased by 180% (from 14.5 million to 40.6 million) between 1992 and 2018….

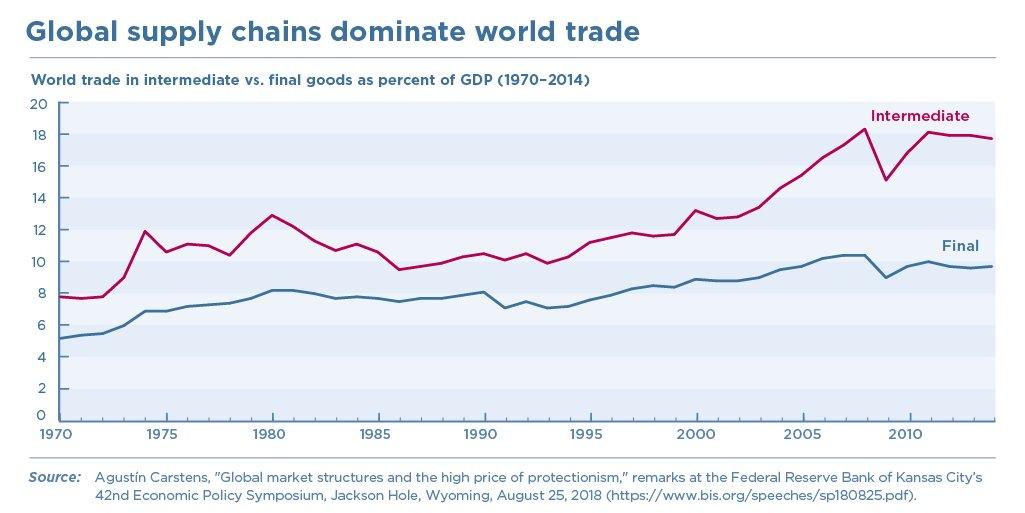

Given these benefits, GVCs have been embraced by consumers and producers alike: Since the 1990s, for example, trade in “intermediate goods” (a decent proxy for supply chain proliferation) has exploded—about doubling trade in final goods by 2018:

Even during the pandemic, trade in intermediate goods continued to rise—a testament to the enduring value of this system, even with the current port and shipping bottlenecks.

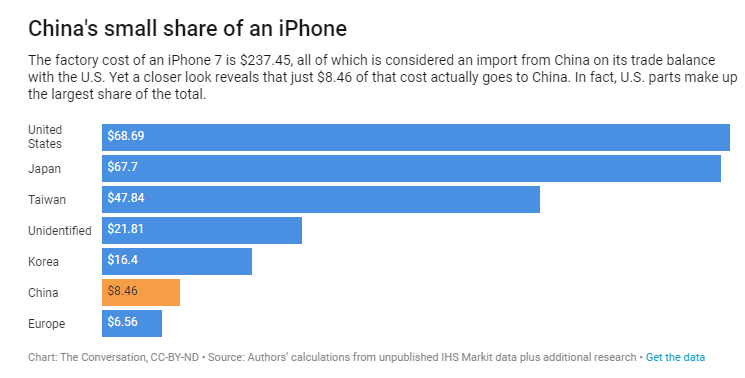

Probably the most widely cited example of GVCs’ immense value is the iPhone, which is designed in the United States but has components made in numerous countries—Germany, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, the United States, and several others—and then assembled and shipped from China and other, low-cost assembly destinations:

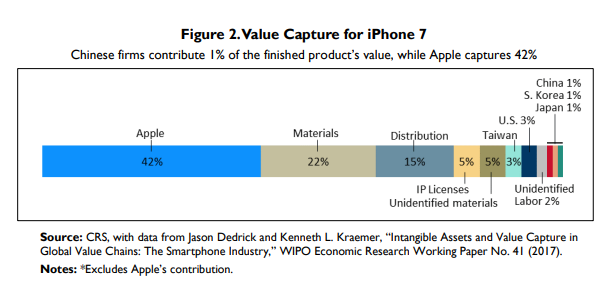

Estimates of how much an “all-American iPhone” would cost U.S. consumers are speculative and vary dramatically—from an extra hundred bucks to an extra thousand or more—but that final number doesn’t really matter for our purposes today, because all analyses agree that Apple’s GVC lowers, not raises, its final price by a significant amount. This benefits consumers, sure, but it also benefits Apple and several American companies, too. As shown in one recent study, for example, companies in the United States derive far more of an iPhone’s production cost than those in China or anywhere else:

Throw in the retail markup, and the pro-American bias here gets even larger:

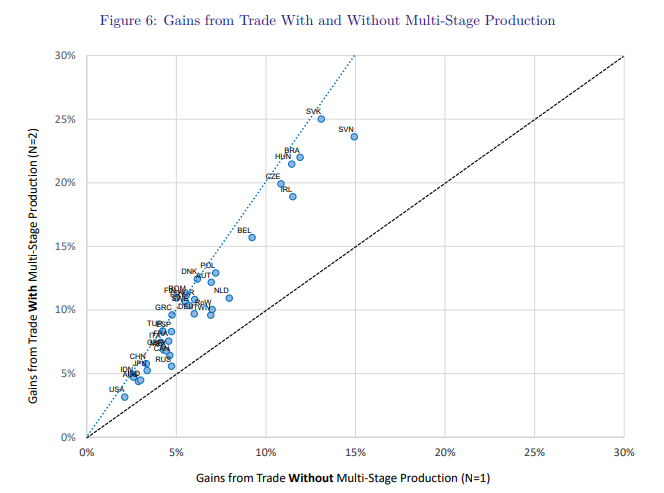

Research shows that these benefits aren’t just limited to Apple (or Boeing or Nike): A recent study from PNAS, for example, finds that GVCs tend to increase productivity along the stages of production, ultimately leading to cheaper final goods and stronger economic growth: “Longer production chains for an industry bias it toward faster price reduction, and longer production chains for a country bias it toward faster growth.” Another found that multistage production processes increased the global gains from trade (i.e., the benefits producers and consumers, including through lower prices) for every country examined and by a whopping 72 percent on average.

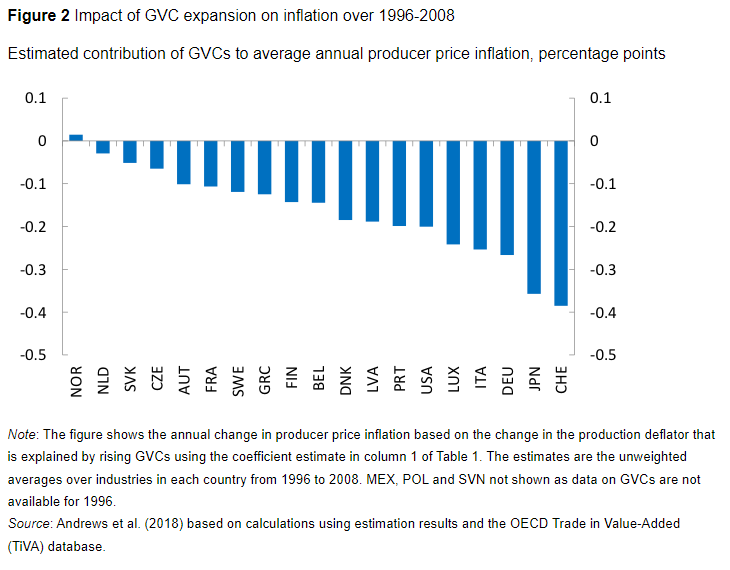

In fact, some studies even show that GVCs temper inflation overall. One found, for example, that “greater participation in global value chains has placed downward pressure on inflation,” with GVCs reducing annual producer price inflation by about 0.2 percentage points in the United States:

This macroeconomic effect is subject to debate, with some corroborating the above conclusion but others finding little to no effect. But nobody that I know of is seriously arguing that GVCs increase inflation—at least in normal times (and more on that in a sec).

On the other hand, studies do show that efforts to expand U.S. manufacturing via tariffs or relocation incentives would likely raise domestic costs, not lower them, in the longer term. Indeed, a 2021 OECD policy analysis estimated that moving toward a more localized U.S. economy would reduce economic efficiency (meaning, higher production costs) and thus reduce both real U.S. GDP and domestic production by about 7 percent. Another found that decoupling from global value chains—in whole or in part (e.g., just China)—would increase costs and decrease welfare in the United States. These findings, of course, make perfect sense: The loudest calls for protectionism and economic isolationism stem from not from inflation hawks but from workers and companies complaining that they can’t compete with “cheap” goods and labor from overseas. If imports were just as expensive as domestically produced counterparts then there’d be no need (excuse) for government protection—to “level the playing field”—via our anti-dumping law and other government measures.

And there’d be no need for GVCs.

At the same time, there’s little evidence that reshoring supply chains would help the country withstand economic shocks. The two studies noted immediately above, for example, found that an economic shock abroad would hit a “decoupled” U.S. just about as hard—in terms of stability or welfare—as our current, “globally integrated” one. And these meager benefits would come with the aforementioned economic costs.

As we’ve discussed, moreover,, insulation from foreign shocks simply makes a nation more susceptible to domestic shocks (like, say, a freak ice storm in Texas)—a conclusion confirmed by a brand new World Bank study, which found that GVC supply shocks are actually less volatile than local supply chain shocks for 90 percent of all countries and sectors worldwide. This is because local supply chains are less able to quickly adapt to a local shock. And because of trade restrictions associated with localized supply chains, domestic consumers end up bearing more of a shock’s economic burden than they do with GVCs. Real-world evidence bears this out: I’ve written repeatedly on how products dominated by American production, such as food or pickup trucks, have proven to be just as problematic in 2020-21 as their ”globalized” counterparts, if not moreso.

A Permanent Pandemic?

Given all of the above evidence, the only way an “anti-inflation reshoring plan” even remotely makes any sense is to assume that the pandemic economy of 2020-21 is our new global normal. Then, perhaps, you’d be trading the high costs of autarky with the even higher costs of GVC-specific issues, such as port bottlenecks. (This theory still raises other economic problems, but we’ll ignore them for now.) However, there are at least two big, non-medical reasons why this isn’t the “new supply chain normal.”

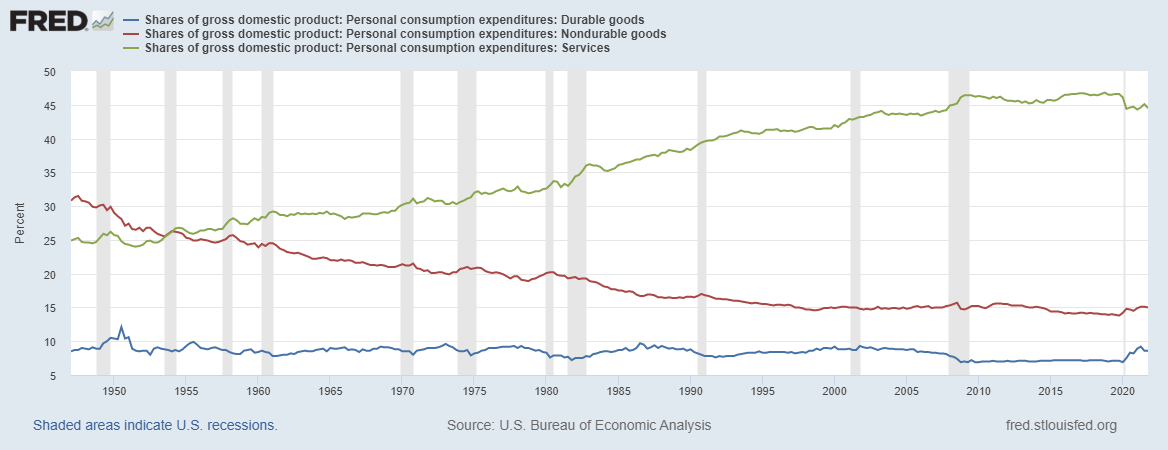

First, the stimulus-backed domestic spending of the last two years is unlikely to continue much longer, with significant implications for recent bottlenecks. One of the big factors driving our current inflationary moment is that the unprecedented amount of monetary and fiscal stimulus implemented after COVID-19 hit was channeled into durable goods like cars and furniture, putting massive pressure on the global supply chains (and related infrastructure) upon which those goods rely. New research from the Federal Reserve, in fact, estimates that U.S. stimulus packages caused a 2.5 percentage point increase in inflation because stimulus checks boosted domestic demand for durable goods but did not (could not) produce a corresponding increase in supply of those goods, thus increasing prices. A February 2022 analysis from Morgan Stanley found basically the same thing, calling this trend the single largest factor in the rise in inflation. Meanwhile, spending on services has been depressed: The St. Louis Fed found for example, the pandemic recession was unique in that demand for durable goods rebounded quickly (and kept rising above normal levels), while demand for services plummeted in 2020 and still hasn’t recovered to pre-recession levels even 18 months after the peak. (Biden himself acknowledged the situation in a November speech in Baltimore, blaming inflation on “higher demand for goods” caused by stimulus checks, higher wages, and pandemic-related barriers to in-person services like restaurants.)

This channeling of stimulus-soaked demand into goods and away from services inevitably affected manufacturing GVCs, which had their own pandemic-related hiccups and simply couldn’t handle the extra volumes for practical and policy-related reasons). The World Trade Organization estimates, for example, that increased demand for goods is a major factor behind supply chain issues, accounting for anywhere between 65 to 75 percent of supply shortages.

However, few (if any) expect consumer spending patterns to continue once the pandemic fully subsides. For starters, the Fed is already tightening monetary policy, and there are no plans for cutting additional stimulus checks to individuals and businesses. As the pandemic wanes, moreover, American spending patterns should shift back from goods to services, resuming their normal, historical balance. As I showed in a 2020 paper, for example, the trend of increased U.S. consumption of services and decreased consumption of goods has been going on for decades – “U.S. consumers were allocating half of all their spending on consumption to goods… in 1960 but only 33 percent by 2010”—and is par for the course for developed economies. (It’s a standard story of economic development: as a country’s residents get richer, they tend to need—and thus buy—fewer goods and spend more of their still-increasing incomes on services.)

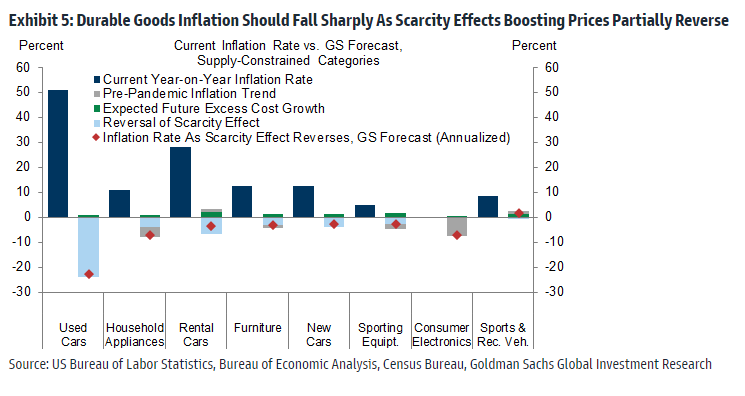

As shown in the chart above, Americans’ spending on goods remains elevated above pre-pandemic levels, but—as the Wall Street Journal noted last month—it’s fallen substantially since the start of the pandemic and is expected to fall even further in the coming months as warmer weather and falling infection rates push Americans to return to their traditional spending patterns. In fact, Goldman Sachs estimates that the forthcoming reversion to a more normal goods-services demand balance in the United States, along with increasing inventories and production, will put downward pressure on the prices of certain durable goods later this year:

As Harvard’s Jason Furman noted earlier this week, this shift in U.S. demand doesn’t necessarily mean that inflation will totally cool off (prices of services could instead climb), but it does mean that the current pressure on manufacturing supply chains should abate significantly this year—long before any government-goosed domestic production comes online (typical!).

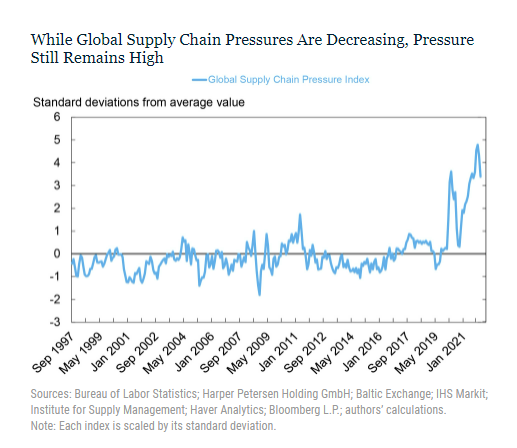

Second, those supply chains are—and stop me if you’ve heard this before—already adjusting to meet new consumer demands and market or geopolitical realities. This includes adding capacity here and abroad, rethinking standard logistics models, and embracing new technologies—for producers, shippers, retailers, and consumers—to better address supply chain hiccups. As a result of those moves and the aforementioned changes in demand (plus some limited deregulatory actions), supply chain stresses, while still very much real, are starting to show signs of easing. In February, for example, the WTO reported that the backlog at American ports has been improving, and the New York Fed’s global supply chain pressure index notched its second monthly decline after peaking late last year:

The index for just the United States also started to ease in 2022, as did indices for Japan, Europe, the U.K., Taiwan, China, and South Korea. Companies are reporting similar things on the ground. In February, for example, consumer technology giant Foxconn reported that its component shortage for iPhone production has begun to improve, while the CEO of shipping behemoth Maersk—which just made a major investment in U.S. freight services—recently predicted that supply chain snarls will ease in the second half of 2022. (“He said demand for manufactured goods should wane as people return to work and spend more on services like travel and entertainment.”) Morgan Stanley predicts much the same. There’s surely a lot of uncertainty here—other forecasts aren’t as rosy—but most everyone believes that supply chain problems will get better relatively soon. This is not the “new normal.”

In short, reshoring only might make sense in a world where stimulus funds keep flowing, American goods consumption remains abnormally high, GVC infrastructure never adapts, and pandemic-related problems persist not merely for a few more months but for the years it would take for new domestic production to come online. All these assumptions are far-fetched, at best.

Ignoring So Much

Perhaps the most frustrating part of this whole episode is that, to the extent microeconomic fixes might alleviate some inflationary pressures in the United States, there are plenty of U.S. policies that Biden could target—policies that needlessly restrict supplies and raise costs yet are not only ignored by this administration but often actually celebrated. We’ve covered a lot of these in past columns, so I won’t rehash it all again here. (Right-leaning John Cochrane provides a good overview of possible reforms in this new essay, several of which left-leaning Larry Summers also just endorsed.) But a few are still worth repeating because—unlike Build Back Better (or whatever they’re now branding it)—Biden could act today, without Congress, to provide immediate relief for American companies and consumers. Instead, he’s doubling down.

-

The president could immediately nix Trump’s tariffs on metals (steel and aluminum) and Chinese imports, which have been repeatedly found to increase costs for American consumers and producers. Biden’s recent metals quota deals with Europe and Japan, plus numerous administration statements on China, indicate that these consumer taxes—which Biden’s own treasury secretary says are contributing to inflation—are not going anywhere anytime soon.

-

The president also has leeway on granting waivers for Buy America procurement rules and Jones Act shipping restrictions, both of which raise costs for American companies and the federal government. Because of the Jones Act, for example, “it costs two or three times as much to ship petroleum products from Gulf Coast refineries to East Coast cities (or from Texas producers to West Coast refineries than it does to bring those products in from ports in faraway countries,” while U.S. metro cars subject to Buy America mandates are 34 percent more expensive than the same products procured by foreign governments. Yet Biden is a longtime Jones Act supporter (never mind that SOTU line about “goods moving faster and cheaper in America”) and just proposed new regulations to make Buy America rules even costlier by reducing the supply of qualifying products and raising the price premium (“enhanced price preferences”) for certain “critical” goods!

(Sorry for yelling. It’s truly a miracle that I don’t have a serious drinking problem.)

On an optimistic note, Cochrane’s essay reiterates what I noted a few weeks ago about a burgeoning group of serious, center-left wonks finally coming to grips with the “supply side” of U.S. economic policy and the many restrictive laws and regulations that today keep costs high. So maybe there’s some hope for the future.

If Biden’s current plans are any indication, however, we’re gonna have to wait a while.

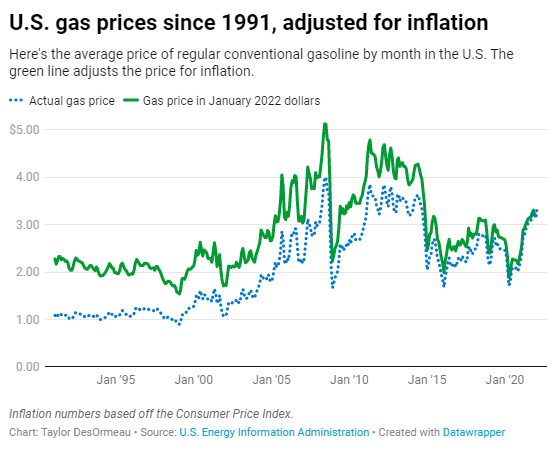

Chart of the Week

“When adjusted for January 2022 dollars, gas prices hit $5.12 in July 2008. Gas prices topped $4.60 per gallon on average in inflation-adjusted dollars in 2011 and 2012.” (source)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.