Dear Capitolicos,

With only a week to go before the 2024 campaign season begins, today’s pretty much the last chance for Capitolism to evaluate 2020 candidate policy. Having already done that a few times for President Trump, I think it’s only fair to spend today looking at one of the more documented and analyzed portions of Democratic nominee Joe Biden’s proposed platform: his tax plan. (You can read my review of Biden’s potential trade policies here.) So that’s what we’ll do today, and I’ll save my Nachifesto for next Tuesday when literally no one on the planet will be caring about policy.

Should We Even Pay Attention to These Proposals?

Before we begin, however, an important disclaimer: As I’ve noted previously, “presidential campaign policies” do not necessarily become “White House policies” and instead merely reflect political calculations about what voters—especially key voters in key states—want to hear. Furthermore, even if a campaign proposal is what the candidate wants, it still has to be implemented, and that usually depends (for domestic policy, at least) on Congress—a body that could very well be led by the opposition party and, regardless of who’s in charge, would be subject to majoritarian processes that inevitably breed horse-trading and political calculation. This is especially the case for tax policy, given Congress’s constitutional role over revenue measures and its legislative expertise.

Nevertheless, campaign proposals often do form at least the starting point for future law, and the White House is increasingly involved in legislative plans and compromises. The proposals also tend to give us an idea of what the candidate—and his or her party—want to do, if given a governing mandate. So, to the extent that policy still matters at all in deciding elections (an open question indeed!), analyzing these plans remains worthwhile—just in case any of you out there are still crazy enough to be undecided.

How Should We Grade a Tax System?

Obviously, my opinions on Biden’s tax plan will come from the fiscally conservative, free-market perspective, but there are—I think—some objective metrics for assessing the plan, in terms of achieving various goals that apply to any tax plan:

-

Raise revenue. Most basically, a tax system raises revenue for a government’s operations and policy priorities. But this simple objective becomes more complicated when you consider that (1) certain tax increases—for example prohibitively high rates that discourage growth or push people/companies to leave the jurisdiction at issue—might actually decrease revenue; (2) “revenue maximizing” tax rates often conflict with other policy goals, especially economic growth; and (3) economists differ wildly on what the “revenue maximizing” rate even is.

-

Promote economic growth and development. A well-structured tax code can both raise revenue and promote economic growth, and different taxes do different things. Research indicates that “corporate taxes are most harmful for economic growth, with personal income taxes and consumption taxes [e.g., sales or value-added taxes] being less harmful. Taxes on immovable property have the smallest impact on growth.” Tax systems need not be growth-maximizing (again, there are tradeoffs), but ones that lack consistent, predictable, and neutral rules will inevitably (and unnecessarily) destroy wealth.

In the current difficult economic climate, it’s also important to consider short-term versus long-term growth, as AAF’s Doug Holtz-Eakin recently explained:

[T]here is a big difference between near-term and long-run growth. Long-run growth is about… tradeoffs…. Higher taxes will hurt growth, the spending will help in some cases and not others, and the ultimate call depends on your values. Near-term growth is about recovering from the pandemic. When it comes to business cycles, the empirical work indicates that tax increases have a much more detrimental impact than the stimulus of the proposed spending programs.

-

Attract/keep global talent. The Tax Foundation has a good rundown of the issue:

A competitive tax code is one that keeps marginal tax rates low. In today’s globalized world, capital is highly mobile. Businesses can choose to invest in any number of countries throughout the world to find the highest rate of return. This means that businesses will look for countries with lower tax rates on investment to maximize their after-tax rate of return. If a country’s tax rate is too high, it will drive investment elsewhere, leading to slower economic growth. In addition, high marginal tax rates can lead to tax avoidance.

The same goes for people, albeit to a lesser extent. Punitive taxes can discourage innovative high earners from coming to or staying in America (hence why wealth-taxers like Elizabeth Warren propose punitive “exit taxes” to discourage people from leaving).

-

Minimize distortions (including compliance/enforcement costs). Tax systems that are not clear, neutral, and relatively simple can also cause all sorts of economic distortions (intended or not), such as favoring consumption over saving, discouraging family formation, creating bubbles in certain industries (e.g., housing), or benefiting big businesses at the expense of small ones. One such distortion is non-compliance, as Cato’s Chris Edwards explains:

The simpler the system, the easier it would be for the IRS to collect taxes on high earners such as Trump. Unfortunately, both parties in Congress have conspired to impose a tax system of ghastly complexity, which has made it easier for some high earners to slip through the cracks.

Then there’s the cost of compliance (filling out forms, hiring accountants), which a brand new study pegs at about 1 percent of GDP per year for personal returns alone. Ouch.

-

Achieve social priorities. Finally, tax systems very often reflect social priorities, such as encouraging children, supporting the poor or elderly, or reducing income inequality. Regardless of whether one thinks such policies are good or bad, it’s essential to understand the tradeoffs at issue, as Holtz-Eakin explains with respect to climate change: “the transition to clean energy is a cost to the economy. That costly transition will not raise growth (unless you only measure narrowly in solar panels or the like), but it will lead to fewer greenhouse gas emissions. That benefit might be enough to justify the policy, and that is the point. Supporting clean energy is not about growth. It is about abating emissions being more important than growth.”

What Kind of System Do We Have Now?

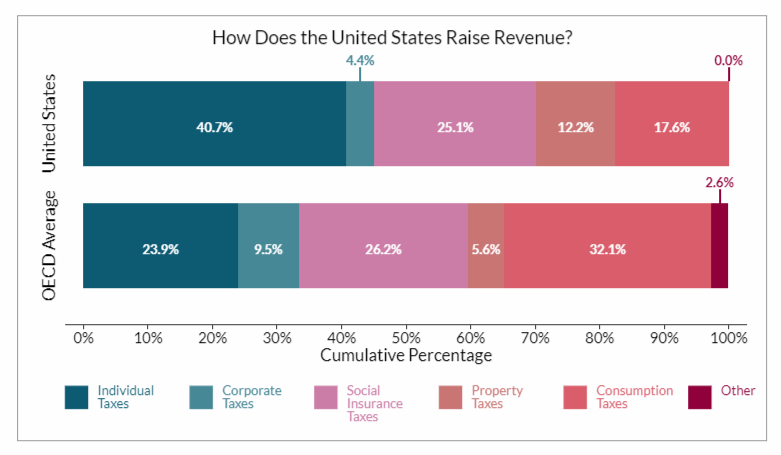

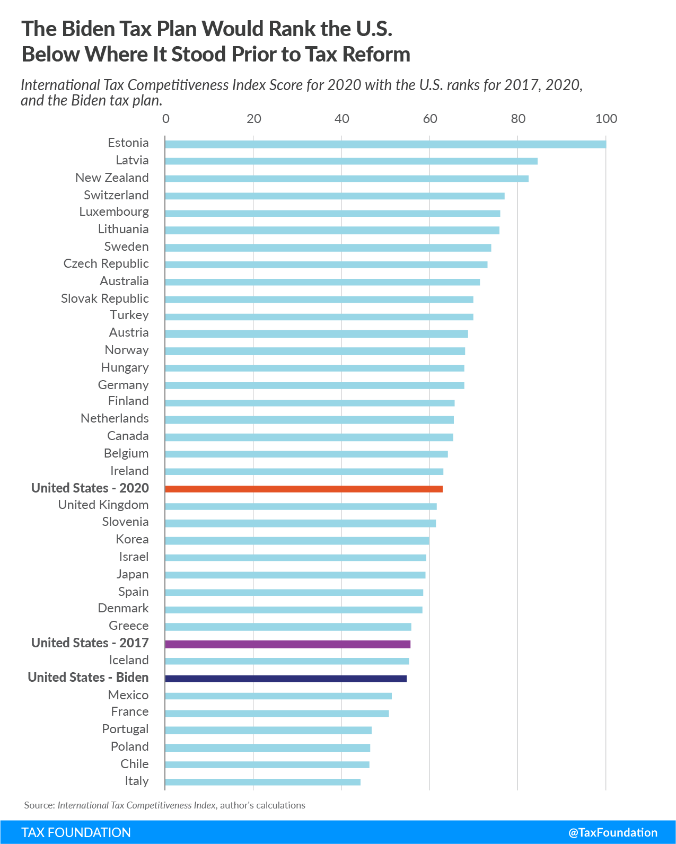

Before we get to Biden’s tax plan, it’s important to understand what we have right now. In short, even after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the United States’ current tax system does a mediocre job achieving the priorities above. The Tax Foundation, for example, finds that the United States ranks a middling 21st on its international tax competitiveness survey—worse than not only the nations you see below but also countries like Sweden, Australia, Norway, Germany, and Canada (hardly conservative bastions!):

For those interested, the Tax Foundation also provides a fantastic in-depth look at our entire tax system, but for our purposes the following charts will do:

Chris Edwards also provides this current look at where individual tax rates are at this point:

For more on tax and fiscal policy in the Trump era, see this recent newsletter.

What Would Biden’s Plan Do?

Using the aforementioned metrics, let’s now see what Biden’s tax plan would do if enacted.

Revenue

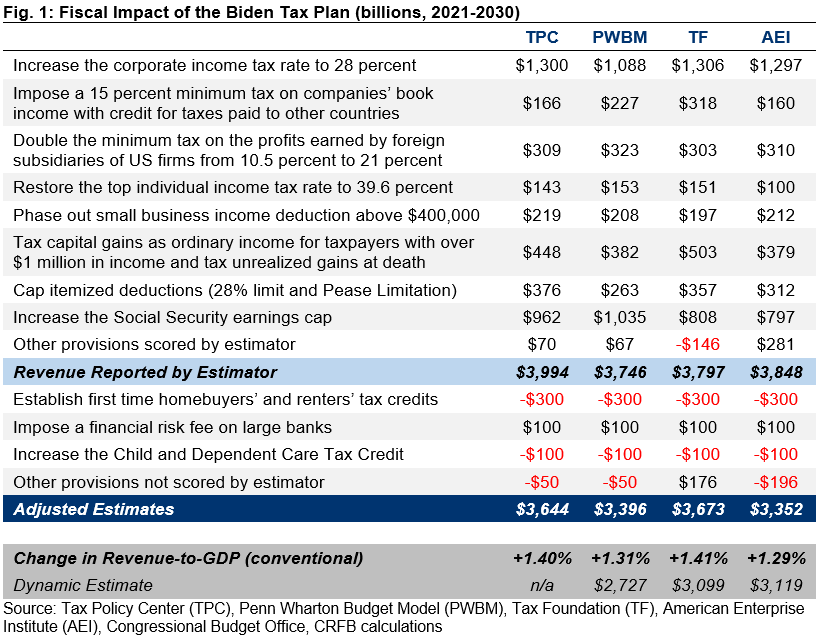

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget provides a great summary of the major and minor changes that Biden’s plan would make to the U.S. tax code and their fiscal impact, as analyzed by several independent groups (Tax Policy Center, Penn-Wharton Budget Model, Tax Foundation, and AEI). Digging in to each of these is well beyond the scope of this newsletter, but the general consensus among these and other tax experts is that Biden’s plan would raise somewhere between $3 trillion and $4 trillion in new federal revenues between 2021 and 2030, mainly (but not entirely) through higher taxes on corporations and high earners.

Growth

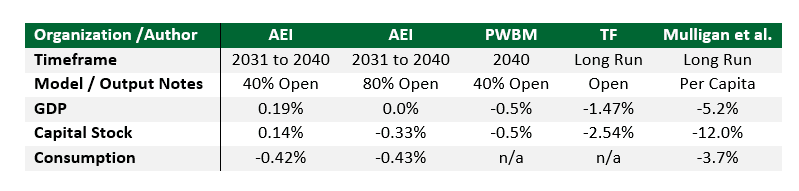

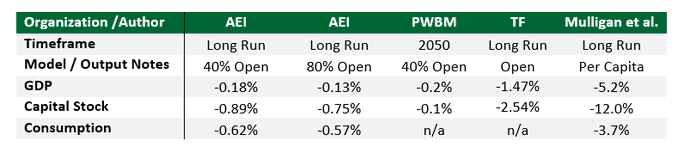

These same groups also tend to agree that the Biden plan would have a small effect on both short-term and long-term economic growth, with most analyses pointing negative (but, again, by a relatively small amount). Economist Donald Schneider—who’s a great follow on Twitter if you’re into the fiscal nerdery—helpfully summarizes the various estimates in the table below, which tend to fluctuate based on the model used (an economy open to foreign investment or one more closed, which affects the extent to which U.S. borrowing “crowds out” private investment).

As you can see, one study—the Hoover Institution’s by Trump CEA Alums Kevin Hassett and Casey Mulligan (and others)—projects that Biden’s tax plan will have far more serious economic harms than all the others:

However, as AEI’s Kyle Pomerlau (who co-authored their analysis) first noted and Bloomberg News subsequently investigated, the Hoover result is driven by assigning the 2026 expiration of Trump’s tax cuts—which were part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and are baked into current law (the “baseline”)—to Biden, even though (1) Trump and a GOP-led Congress implemented the TCJA (and made the tax cuts sunset so they could keep deficits in check); (2) it would require an affirmative act of Congress (and the president) to extend the tax cuts beyond 2026; and (3) the last time we had this type of situation, President Obama actually made many of the Bush tax cuts permanent when they were scheduled to expire in 2012. Even though Biden has said he’d allow the TCJA provisions to expire, it strikes me as a bit disingenuous to assign current law to Biden, without at the very least offering an alternative calculation with the actual current baseline (which all other analysts have done).

Social Objectives and Complexity/Distortions

As shown in both the CRFB table above and in the one below that expands the smaller, “other provisions” that Biden has proposed, the Biden plan pursues various social objectives but in doing so increases tax complexity and (probably) economic distortions:

Maybe you think these provisions are worthwhile; maybe you don’t. Each one could merit its own column debating costs, benefits, and efficacy. (I am, as you can imagine, skeptical.) But what really shouldn’t be up for debate is whether they will increase the complexity of our tax code, with all of the costs that that entails. They will. Caveat emptor.

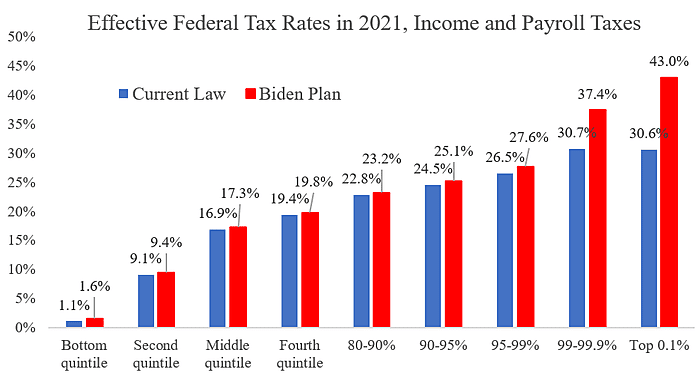

Another core social objective of the Biden tax plan is “fairness,” which is really just code for “making the tax code even more progressive.” And the plan achieves this goal in spades: As noted above, most of Biden’s direct tax increases or changes would be borne by higher-income Americans, and the tax code would thus become even more progressive than it already is. Just how progressive? Well, the Tax Foundation projects that Biden’s plan would push total (federal/state/local) marginal tax rates for the highest-income Americans to levels not seen since 1986, and to more than sixty percent for people living in California (62.64 percent), Hawaii (60.34 percent), New Jersey (60.09 percent), and New York City (62.03 percent). Plenty of non-rich people (like me!) object to confiscatory taxes for ideological and economic reasons—see, for example, this brand new paper on the perils of using progressive taxation to fight inequality in the United States—and Biden’s plan is certainly no exception, regardless of how few people those top rates would affect (in this case, not many).

However, it’s disingenuous to say that Biden’s plan wouldn’t raise taxes on the non-rich. First, most groups agree that Biden’s corporate taxes would impose additional, indirect (but still relatively small) tax burdens on non-rich Americans because those taxes are—as shown in numerous economic analyses—borne not by the corporations themselves but by a mix of investors, workers, and consumers. The Penn-Wharton Budget Model helpfully shows how this works by providing distributional estimates for the individual/payroll tax provisions only and then adding the corporate taxes. Cato’s Chris Edward has summarized the latter:

Other studies come to the same conclusion, with small declines in after-tax income for everyone outside the top quintile of earners and significant decreases for the top 1 percent:

Second, Biden’s corporate taxes would also act as a stealth “wealth tax,” increasing current taxes on capital accumulation from about 3 to 4 percent to close to 6 percent. A similar analysis found that Biden’s corporate tax measures “would lower earnings at companies in the S&P 500 by more than 10%”—potentially lowering returns for the 55 percent of Americans who own stock. Sure, much of this wealth is concentrated among the richest Americans (who would thus face the biggest tax hit), but many other Americans would take a hit too.

Tax Competitiveness

Given all of the changes above, it’s pretty clear that Biden’s plan would not improve the U.S. tax code’s international competitiveness—i.e., our ability to keep and attract innovative businesses and individuals. According to Tax Foundation’s Daniel Bunn, in fact, it would make us significantly less competitive:

From the standpoint of the International Tax Competitiveness Index, the corporate and individual tax hikes envisioned by the Biden campaign would push the U.S. down the rankings to 30th place, even below where the U.S. stood prior to tax reform. On corporate taxes, the U.S. rank would fall from 19th to 33rd. On individual taxes, the U.S. rank would fall from 23rd to 36th, last for individual taxation.

Part of the reason for this result is that other countries (e.g., Canada and France) have improved their tax codes since the TCJA was passed. In other words, the Biden plan would take the United States one step backward right after several other countries had taken a step forward.

Summing It All Up

So where does that leave us? Well, as you can imagine, I’m not a big fan of the Biden plan, but it also could’ve been a lot worse. Overall, the multiple independent analyses above show that Biden’s plan (1) would pursue several Democratic Party social objectives at the expense of simplicity (certainly) and international competitiveness (probably); and (2) wouldn’t boost economic growth (at a time we desperately need it) but also wouldn’t hurt it much, unless you assign current law to a future President Biden.

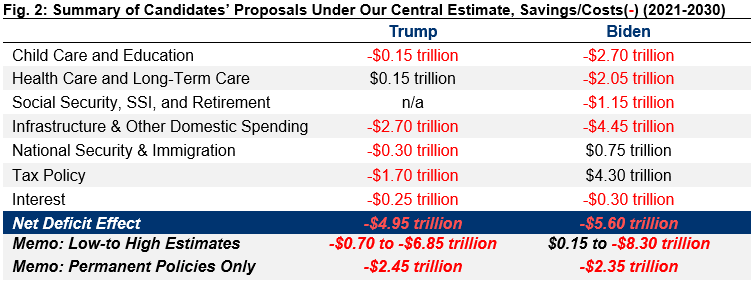

So that leaves revenue. Here, the Biden plan is uniformly projected to raise significant amounts of additional revenue over the current baseline. However, Biden has also promised to raise federal spending far above the same baseline, thus eliminating most or all (if not more) of the savings that could be used to pay down the debt and improve the United States’ troubling fiscal trajectory. The CRFB provides one such estimate below when it compares the tax and spending plans of the two candidates (red ink is revenue losses, black ink is gains).

The long-run projections, as you can imagine, get murkier and depend on assumptions about spending, taxes, and macroeconomic effects that (in my opinion) make them pretty useless. Regardless, Team Biden clearly intends to use any new revenue generated by their tax plans to finance new spending, not to pay down the debt.

Combine that fact with the massive recent increase in U.S. debt due to COVID-19 fiscal policy, the current economic situation in the United States, and the aforementioned complexity, competitiveness, and growth concerns that the Biden tax plan raises, and it all strikes me as precisely the wrong policy for the United States to pursue right now.

Fortunately, we’d have to wait until at least 2021 to find out whether it’ll even be proposed, let alone become law. Maybe by then, cooler heads and reality will have prevailed.

Chart of the Week

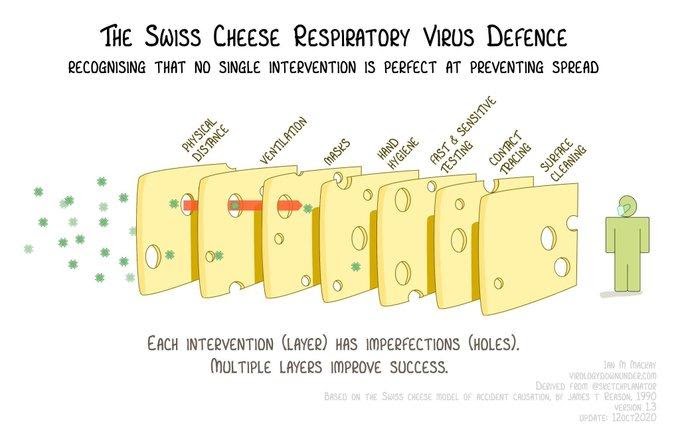

This is a great way of thinking about how to control COVID-19 (source):

The Links

Me on political protectionism and pickup trucks

Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.