In August 2020, The Dispatch ManagementTM asked me to sketch out my predictions for U.S. trade policy under a possible Biden administration. Contrary to the prevailing optimism at the time among many on the centers right and left, my take was pretty measured, predicting some modest improvement over the chaotic and costly Trump 1.0 years, some continuation of Trumpian protectionism (with less bluster), and even some deterioration on things like industrial policy and “Buy American” mandates.

On the second and third points, I didn’t score too badly. On the first, however, I was dead wrong, and with the supremely disappointing Biden years now behind us, it’s time for one last Capitolism Airing of Grievances.

Four Years of Failure

What most sticks out about Biden’s trade legacy is just how little trade it involved. Instead, as we’ve documented here at Capitolism repeatedly, the era was one of U.S. stasis or outright retreat from the global stage. For example:

- Most of Trump’s “national security” tariffs on steel and aluminum remained in force in their original form or as still-restrictive quotas, including on imports from close allies. Trump’s China tariffs were not just maintained but actually expanded near the end of Biden’s term. And while Trump-era global “safeguard” measures on imported washing machines were allowed to expire last year, the ones on solar products were extended for another four years.

- The administration also barely lifted a finger to restart the popular-but-expired Generalized System of Preferences program (which unilaterally grants limited duty-free access to certain developing-country imports) or to extend the similar African Growth and Opportunity Act, which terminates in September. This failure not only cost American companies billions, but also discouraged trade with and investment in some of the poorest places on the planet—including many that are cozying up to China instead.

- Not only did the Biden administration fail to complete any new comprehensive U.S. bilateral or regional trade agreements, it didn’t even initiate any or ask Congress for “trade promotion authority” (the traditional tool U.S. presidents have long used to negotiate new trade deals for eventual congressional approval). Instead, the administration chose to launch things like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework and U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council, which didn’t include traditional trade provisions (e.g., on things like tariffs or services barriers) and were never finished regardless. It also (dubiously) bypassed Congress in seeking narrow bilateral deals on things like “critical minerals,” but those too didn’t get very far. Per my quick research, this marks the first time since the Reagan era that a U.S. president has pulled such a trade agreement O-fer.

- At the World Trade Organization, the Biden administration didn’t just continue Trump-era ambivalence but retreated even further by abandoning a digital trade deal that the United States itself once championed because it would greatly benefit the globally dominant U.S. tech industry. In dispute settlement, meanwhile, the Biden team openly rejected a (mostly correct) ruling on the aforementioned metals tariffs; brought zero new challenges to foreign trade barriers (also unprecedented!); and, perhaps most galling of all, sandbagged the very reform talks that the U.S. alone demanded, thus keeping the organization’s Appellate Body disbanded. (Biden officials literally only engaged formally on the issue a few months ago!). The administration also encouraged the EU to abandon its own WTO commitments by trying to forge a bilateral deal on “green” steel trade—a (bad) plan that also (thankfully) failed!

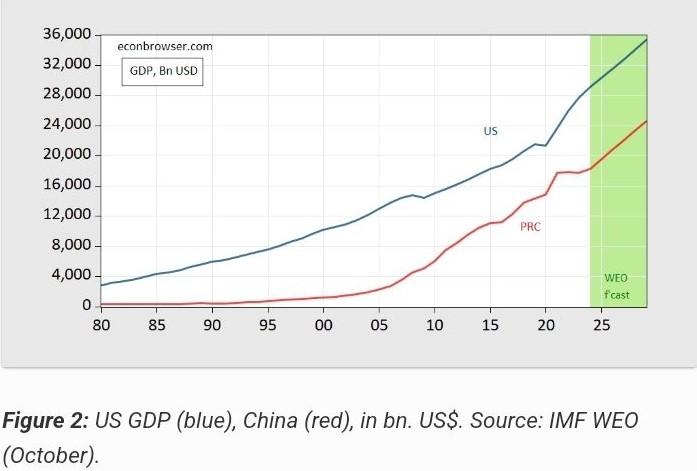

Outside of these traditional trade areas, there were other disappointments. Via industrial policy measures like the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and Inflation Reduction Act and various executive actions, the Biden team expanded “Buy American” protectionism and clamped down on enforcement of existing local content restrictions (e.g., on what qualifies as “American” and on possible waivers). The administration also dramatically broadened China-centric sanctions and export controls, costing American companies billions in lost revenue but failing to seriously dent Beijing’s technological ambitions (and annoying many allies in the process). And then Biden officials capped it all off with the Nippon Steel-U.S. Steel embarrassment and a last-minute, error-riddled report by the Office of U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai on shipbuilding that basically echoes (incorrect) union talking points.

Beyond the lack of achievement was the incoherence—in both rhetoric and policy. On the former, our own U.S. trade representative—tasked by law with being federal government’s chief trade negotiator (and chief trade cheerleader)—frequently parroted left-wing talking points, criticized U.S. trade liberalization (aka “trickle-down trade”!), and praised protectionism. Tai even once went so far as to claim tariffs didn’t raise prices—a position the administration immediately (and hilariously) walked back. Amid all the “polite protectionism,” meanwhile, other administration officials were proud globalists, boldly praising Biden’s work to rebuild international alliances, encourage “friendshoring,” and otherwise boost the United States’ standing in the world.

U.S. trading partners could not be reached for comment.

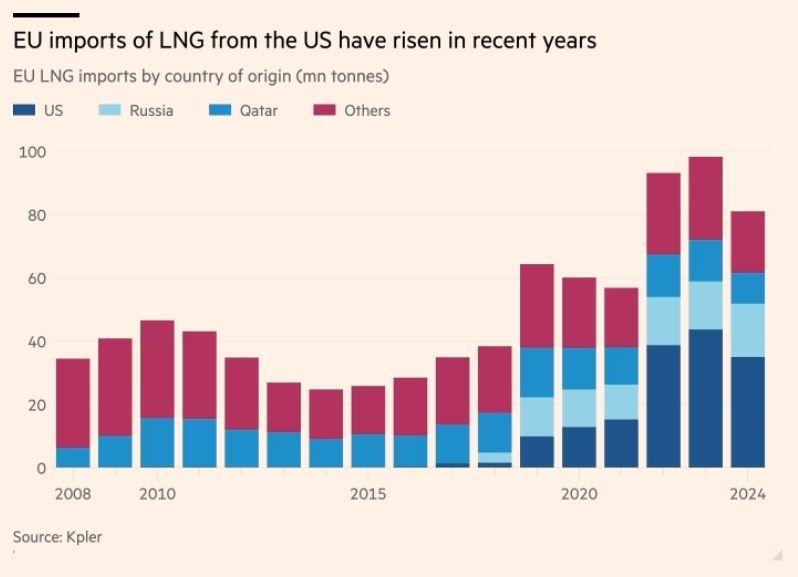

On the policy incoherence, nowhere was this more evident than climate change. At one moment, Biden officials were championing trillions of taxpayer dollars to boost domestic consumption of renewable energy (and thus combat the “existential crisis” of climate change). Two seconds later, they were championing tariffs and Buy American rules—and no, not just to block Chinese products—that directly discouraged the proliferation of “green” technologies (by increasing prices, reducing variety, and delaying deployment). Related policy thus routinely ended up erratic, inconsistent, and sometimes downright contradictory—as we saw with wind, solar, and EVs. Policy toward China was similarly incoherent: Governments around the world were asked to ditch Beijing and join Team America (sometimes at significant economic cost), yet the United States refused to offer the one thing these nations wanted in return: preferential access to the U.S. market. Indeed, they sometimes got more tariffs (and the occasional lecture on labor and environmental rights). Then, the administration topped it all off by calling publicly traded Nippon Steel a national security threat—for having the gall to invest billions in a struggling U.S. steel company—on the very same day the U.S. sold Japan billions in advanced weaponry.

It was all enough to have many foreign governments admit before the election that they were pining for the better trade days of … the Trump administration:

Some foreign governments are reaching an uncomfortable conclusion as election season comes to a head: their best chance for negotiating a trade deal— however arduous it may be—lies in Donald Trump retaking the White House. While Trump derailed decades of free trade orthodoxy with tariffs and other hostile economic actions, his team often used those moves as leverage to strike deals with foreign governments— reforming NAFTA into the new U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement, reshaping pacts with Japan and South Korea, and even striking a short-lived deal with China. Separately, Trump launched new free trade talks with the U.K. and Kenya. Biden, by contrast, swore off pursuing conventional free trade deals out of fear of electoral backlash and a belief from his team— particularly his trade chief— that lowering tariffs won’t help the U.S. economy.

…

The Biden-Harris administration’s unofficial “ban” on new free trade talks has frustrated allies who had hoped they would be more open to new tariff-lowering deals, which are critical for their domestic economies. While Trump is by no means a free trader, foreign diplomats also do not believe he would be as rigidly opposed to lowering tariffs, if the circumstances are right.

Now that the election is over, all but the most partisan and/or protectionist of trade-watchers—not just us libertarian “fundamentalists” (lol)—have declared the Biden era to have been a near-total failure on the international economic front. The Financial Times’ Alan Beattie, for example, offered a “requiem for friendshoring, that abandoned orphan of Bidenomics” that was finally put out of its misery by the Nippon Steel mess. Kori Schake of the American Enterprise Institute called trade a “major deficiency” of Biden’s foreign policy, while the Baker Institute’s Simon Lester politely documented how the administration’s “trade policy for the middle class” didn’t noticeably help many people in, you know, the actual American middle class. Bill Reinsch of the Center for Strategic and International Studies offered an “obituary,” noting that—except for the area of trade agreement enforcement (which can often just be backdoor protectionism, by the way)—the administration failed on its own “pro-worker” terms. “The result,” he adds, “has been a classic case of failure to launch along with a boatload of missed opportunities to expand market access for U.S. exports, notably in agriculture, where we are now in our fourth year of trade deficits after nearly a half-century of surpluses.” And on export controls, Geoffrey Gertz of the Center for a New American Security explained that Biden’s “small yard with a high fence” strategy with China—strong restrictions on a narrow list of core technologies and countries—failed to achieve its (also contradictory) goals of fundamentally shifting global tech competition without “upending the global economic order.” Aside from winning over a few allies like the U.K., Gertz documents, the policy was ill-defined, overbroad, and costly—economically and geopolitically—and teed up Donald Trump to do even more (if he wants).

The Fletcher School’s Dan Drezner perhaps sums it all up best. After detailing how Biden policy fomented the “enshittification of global economic governance” (lol), he concludes:

The Biden administration put an intellectual patina on rank protectionism, and then got offended when anyone pointed out the policy contradictions. And for continuing to justify a foreign economic policy that alienates allies while accomplishing little of economic substance, I will not miss having to write about Biden’s foreign economic policy team ever again.

Woof.

Was Biden’s ‘Trade Policy’ Really About Trade at All?

As these and other postmortems demonstrate, Biden’s “worker centered trade policy” failed on its own public terms. But I’m left wondering whether—contra all the hackneyed jibberjabber about yards and workers and friends and stuff—those things, and trade more broadly, were really the Biden team’s main objectives at all. Indeed, if you think about the last four years of U.S. trade policy as far less about trade and far more about, as Matt Yglesias has popularized, “the groups” that took over Democratic policymaking in recent years (and pushed it far to the left), it makes a lot more sense. In this particular case, the main progressive “group” at issue is U.S. labor unions, who have long opposed any trade liberalization, have more recently seen trade deals as a way to block foreign competition and to guide (bully) foreign labor, environmental, competition, and other nontrade policies; and as we saw with the Nippon Steel deal, have had immense influence over both President Biden and his trade-skeptical trade representative, Katherine Tai.

You can see this, I think, in Tai’s farewell piece in Foreign Policy, which focused on everything but trade—antitrust, labor regulation, the environment, global governance, “economic security for working people,” you name it—and was literally titled “The Real Purpose of Trade Policy.” You can see it in FOIA’d communications between USTR and various left-wing groups. And, as demonstrated by the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity debacle—whereby Tai demanded developed-country standards from developing countries that couldn’t possibly afford them, offered nothing in return (while lecturing these governments that this was all for their own good), and then abruptly walked away when a few union-aligned senators got mad—you can see it in actual U.S. policy too.

In this light, Biden’s incoherent international economic policy starts to gel: It was never really about trade at all. It was about winning elections, about cementing future political support or career prospects, about pushing various progressive domestic priorities (labor, antitrust, etc.), and about keeping the people who actually wanted more U.S. trade and engagement—businesses, farmers, foreign governments, the WTO, etc.—on the hook until the very end. Under this new math, the messy stasis adds up—especially when championed by those angling for a future with “the groups” at issue. (And, to be clear, I’m certainly not the only one who’s noticed.)

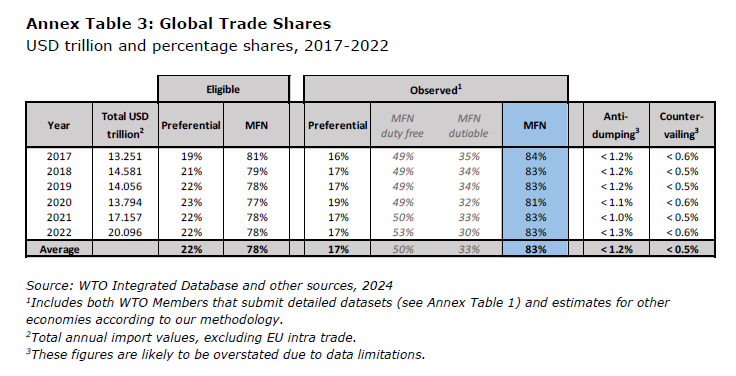

Even this more coherent retelling of Biden’s trade legacy, however, runs into real problems. The first is that, as the United States government was taking a pause on “globalization,” much of the rest of the world—developing and developed alike—was having none of it. A brand new WTO report, for example, calculates that more than 80 percent of all global trade still occurs under the organization’s multilateral rules (MFN column below)—about the same as in 2017 before all the trade wars began.

Nations are also still signing free trade agreements (FTAs)—and have been for years. Since the last new U.S. FTA entered into force in 2012, in fact, other governments have implemented a whopping 131 of them. This includes 17 by the EU, 15 by China, four by Mexico, and 38 by the post-Brexit U.K. (including its accession to the Trans-Pacific Partnership deal that Trump abandoned and to which Biden refused to return). In just the Biden era alone, there have been 58 new FTAs—even as pandemic and war and geopolitical strife and “deglobalization” raged. And, as we’ve discussed, there are plenty of new non-U.S. FTAs under negotiation today. So, while the United States sits still, other nations—including China—are writing the rules on 21st century issues like digital trade; their companies, farmers, and consumers are gaining better access to overseas markets than what their U.S. counterparts now have.

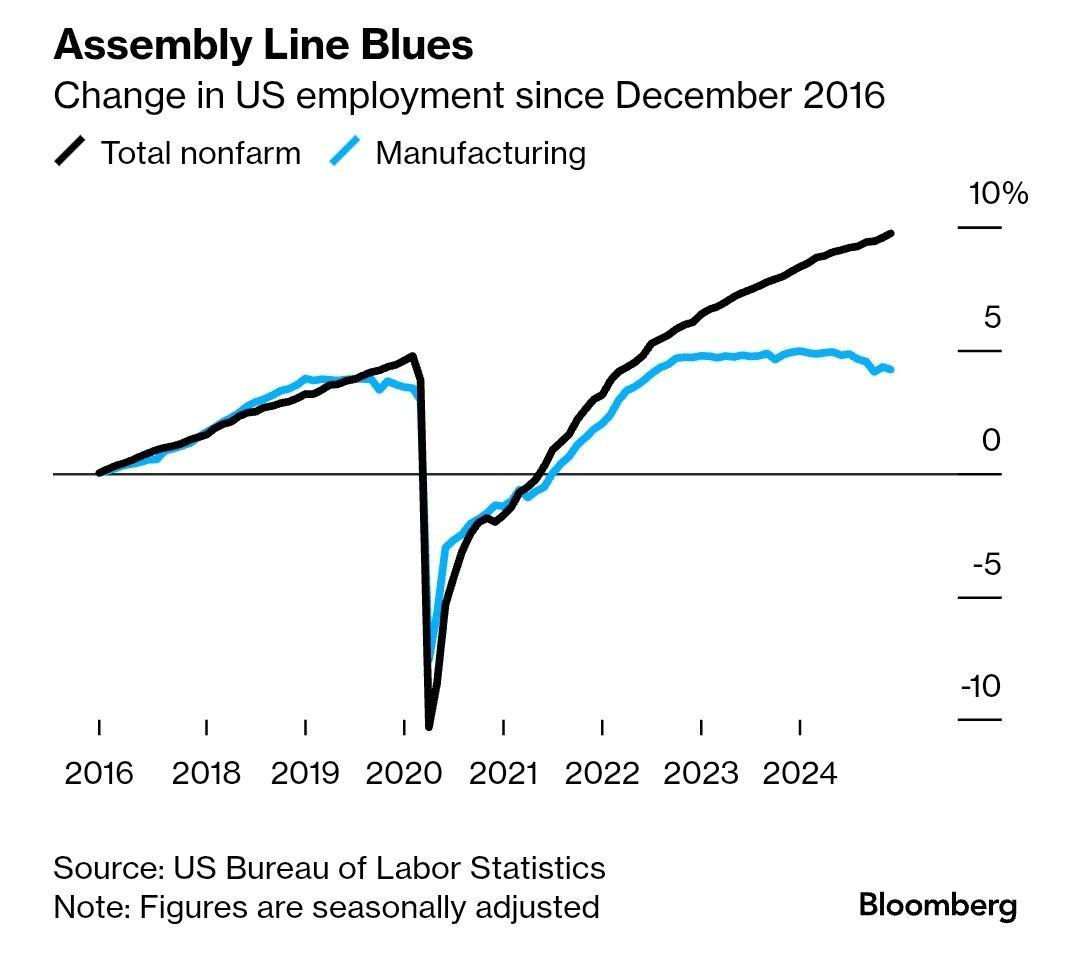

The second problem is perhaps even more obvious: Whether by design or incompetence, all this group-driven policy “failure” didn’t win Team Biden/Harris the election. Maybe that’s because most Americans don’t care about trade policy (ranking it dead last among issue priorities in the Cato Institute’s 2024 survey) or because most workers don’t work in manufacturing or because fewer still are in a private-sector union today. (As the union-friendly folks at the Center for American Progress noted right after the election, for example, “The results from exit polls and voter surveys conducted on Election Day suggest that union voters may have responded more positively to the pro-worker Biden-Harris administration and Harris-Walz campaigns than working-class voters overall.”) Or maybe it’s because most American voters don’t vote on wonky issue particulars at all but instead vote on broad outcomes like the national economy, the job market, and kitchen-table issues like grocery prices—or on entirely non-economic things like culture or candidate personality. Whatever the reason, it’s clear that trying to cobble together a winning political coalition by catering to “the groups” in your policymaking—trade or otherwise—doesn’t just make a mess of policy but also doesn’t guarantee political victory.

But it does probably help you get a job with the groups.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.