Dear Capitolisters,

This week’s edition will be short and chart-heavy, as we’re all busy making Thanksgiving stuffing and traveling to or trying to avoid our families.

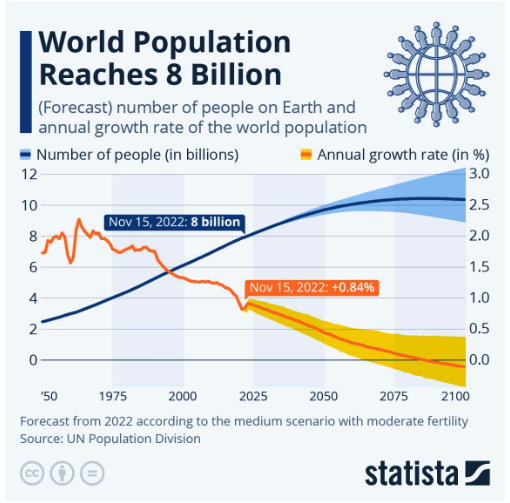

Speaking of giving thanks, last week saw the world welcome—per U.N. estimates, at least—its 8 billionth human. The news was greeted by the usual concern and consternation about population growth, strained resources, and overconsumption—especially in fast-growing places like Nigeria or India. Yet by an array of metrics, the long-term trajectory of life on Earth has been overwhelmingly positive (though, surely, things could always be even better). So this Thanksgiving, I invite you to sit back, pour a warm glass of gravy, and take this moment to be thankful you’re living in today’s world—and especially in today’s United States—instead of the one that greeted its 4 billionth inhabitant back in the good ol’ 1970s.

And here are a bunch of charts to prove it.

Human Health

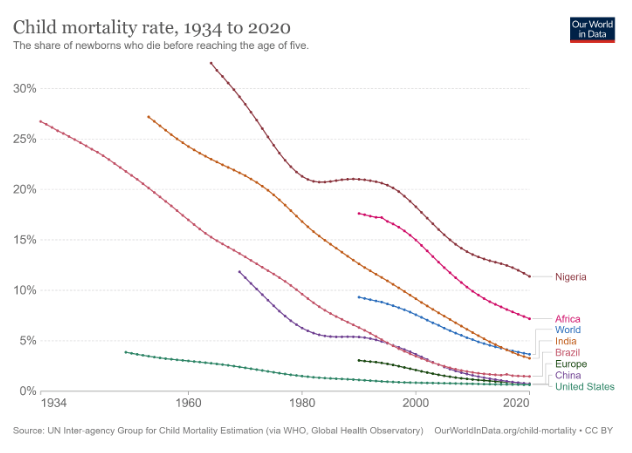

Let’s start with the most basic of issues—human health. Child mortality is down dramatically, in basically every country (feel free to click through and make your own charts):

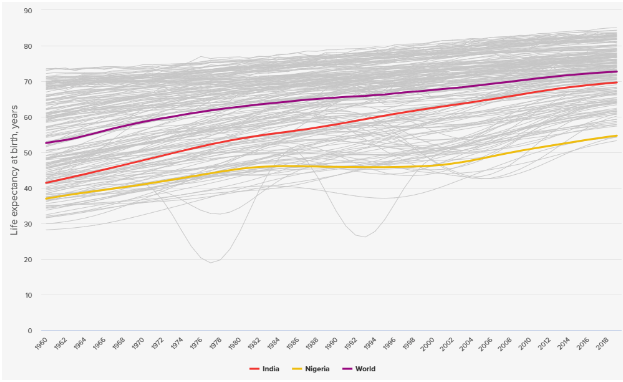

Meanwhile, people born today—almost anywhere on the planet—can expect to live much longer than their counterparts born a few decades ago (gray lines are other countries):

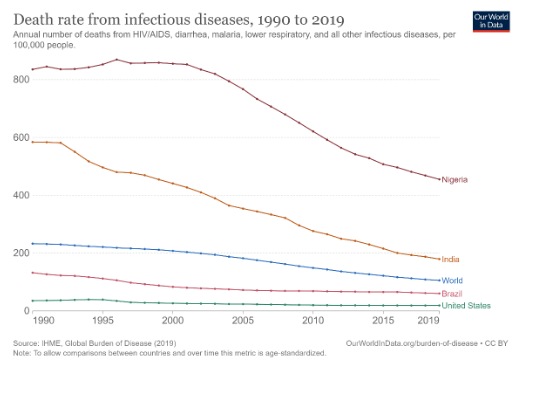

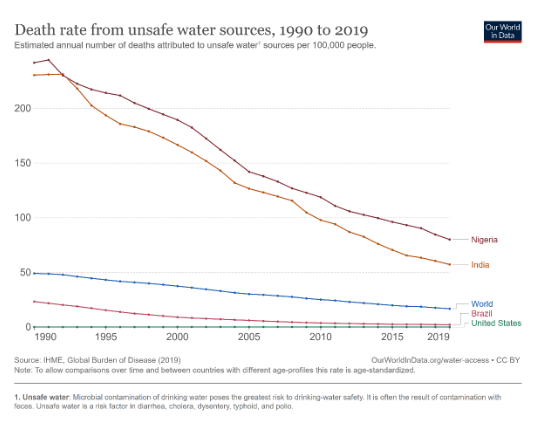

Also, far fewer people are dying from infectious diseases or unsafe water—things we hardly even think about here in the United States but which are a real threat elsewhere.

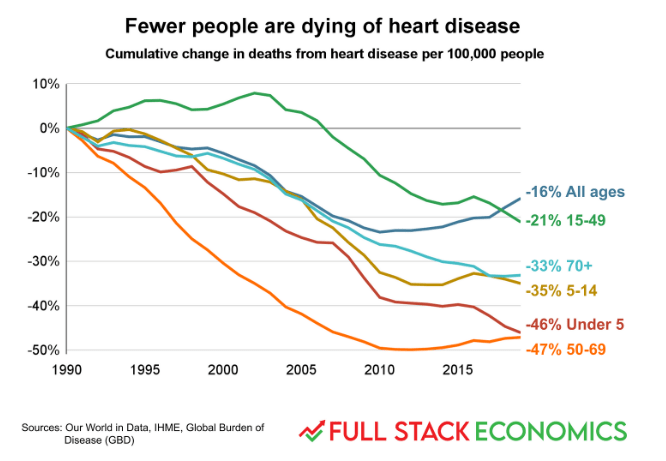

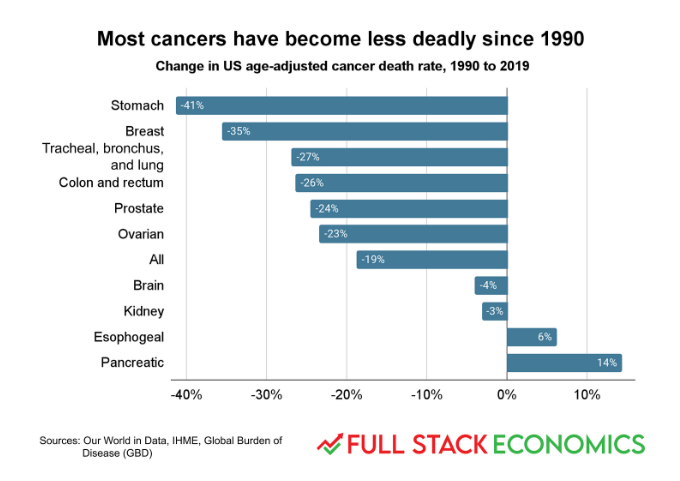

Of course, Americans do have some health issues—obesity, drug use, etc.—but we’re still better off than our parents by all sorts of health metrics, such as heart disease or cancer survival:

As shown at that link, we’re also able to eat healthier, thanks to a bounty of fresh fruits and vegetables that most Americans in the 1970s could only dream of.

Incomes, Poverty, and Work

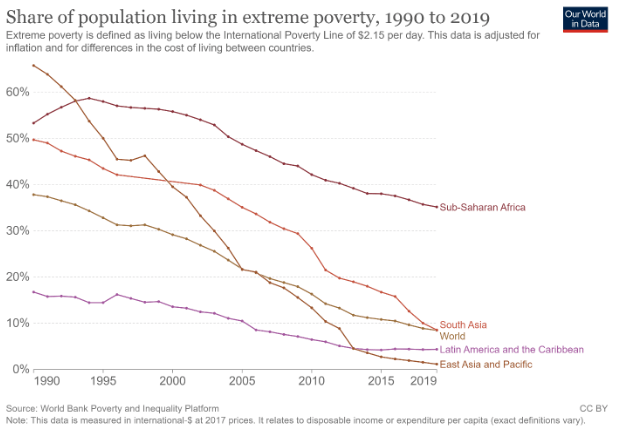

Humans have also gotten wealthier (though, again, there’s still more to do). For example, a person born today is far less likely to live in abject poverty than he or she was just a couple decades ago:

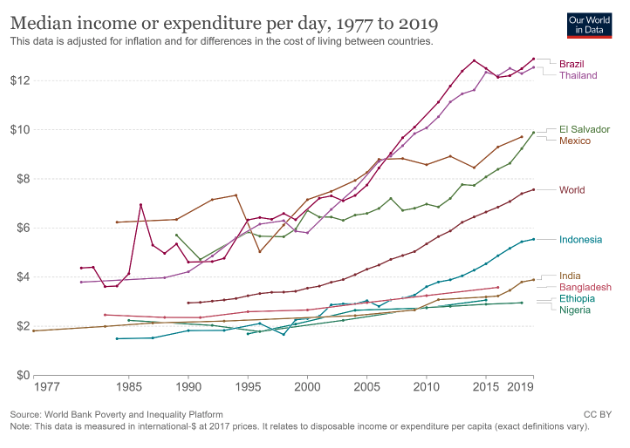

Median incomes have also generally increased—and not simply because of China’s rise, either.

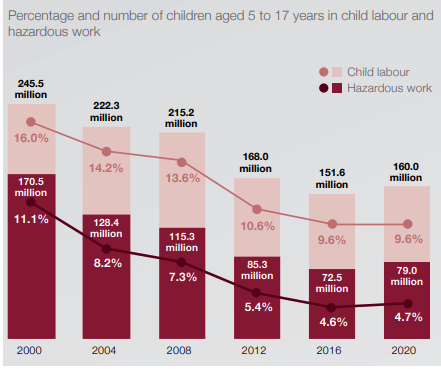

Child labor, on the other hand, has declined over the last couple decades (though the pandemic stunted that improvement):

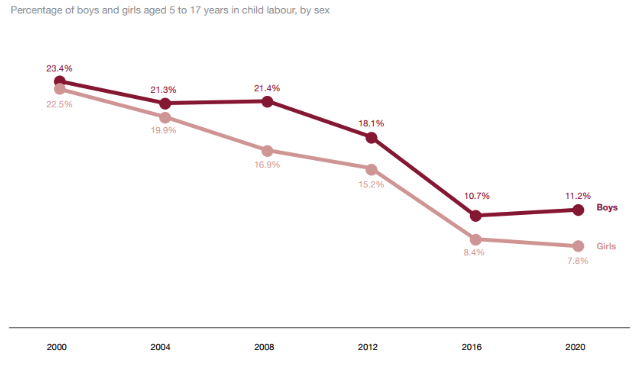

And gains have been particularly pronounced for young girls:

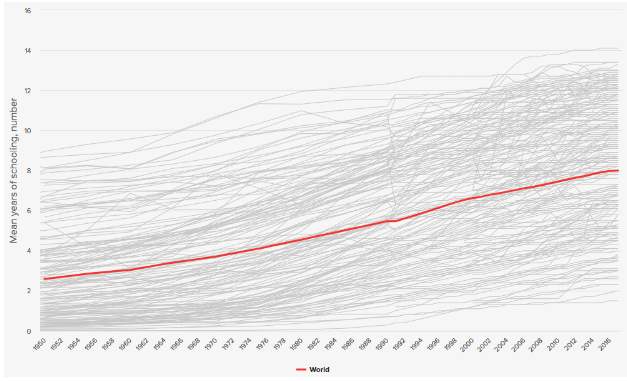

Relatedly, children around the world are getting more years of schooling:

And, finally, it’s important to note that oft-maligned globalization has been a big (though certainly not the only) driver of these gains, and that growth in the developing world didn’t come at the developed world’s expense:

Hunger and Food Production

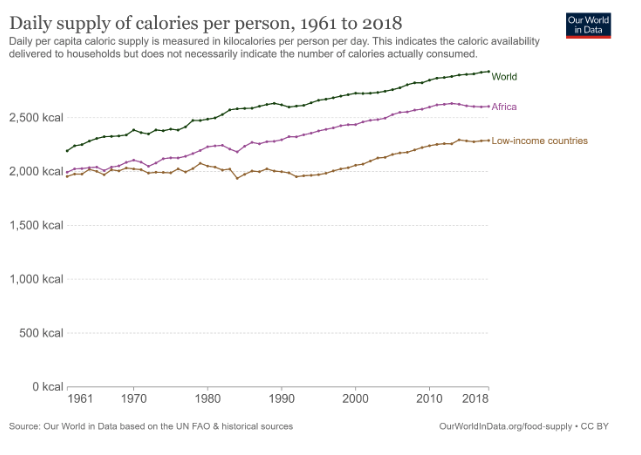

Humans today are also better nourished than they were decades ago. We’re eating more calories (which is a good and important thing unless you’re rich and spoiled in a place like the U.S.):

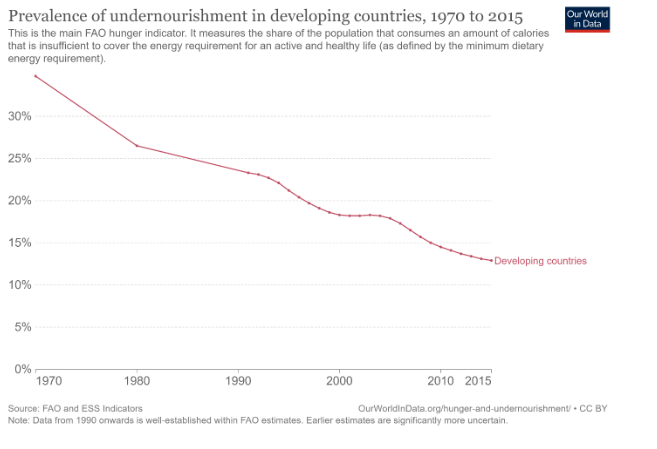

And thus undernourishment has declined substantially:

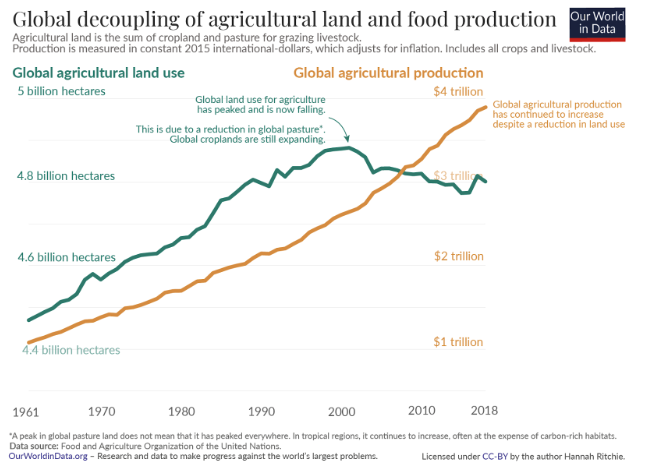

Trade is a big reason for these gains, but another is the dramatic improvement in agricultural productivity (meaning we produce more food with less land):

Resource Abundance and Continued Environmental Gains

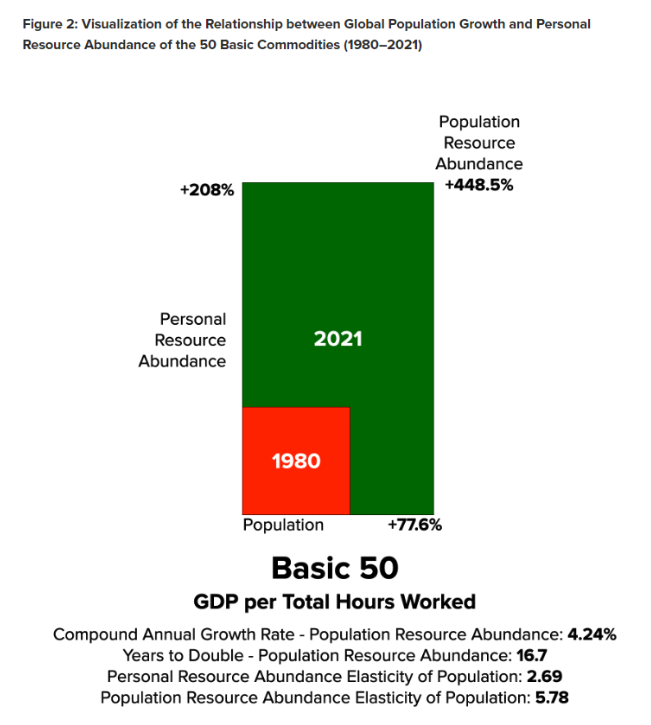

As I noted in my review of the new book Superabundance, a wide range of natural resources have become more abundant—handily outpacing population growth (and thus generating “superabundance”). Here’s one more example from the book (and in this recent article): the abundance of 50 basic commodities—including food, energy, materials, minerals, and metals—since 1980:

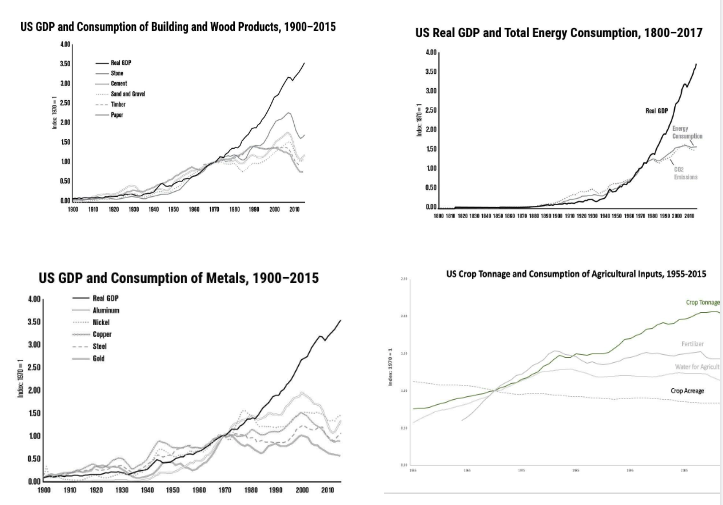

As the Superabundance authors discuss, one big driver of our growing resource abundance is humans’ persistent effort to conserve resources—to “make more from less” (often for selfish, profit-driven reasons—oh no!). This “dematerialization” was documented in a book of the same name, which shows it working through the United States:

OECD data on “material consumption” (i.e., the actual amount of materials used in an economy) show similar trends in Germany, France, the U.K., and many other developed countries.

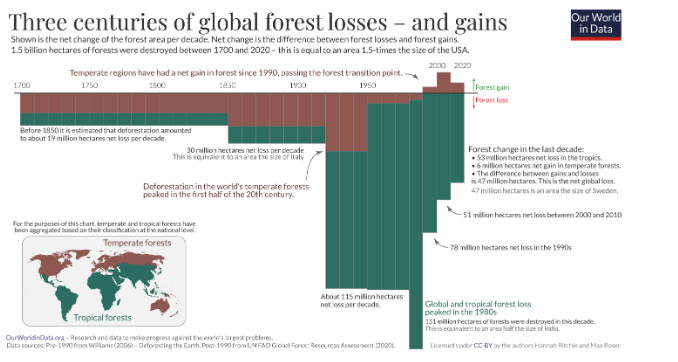

We’ve also apparently turned the corner on deforestation:

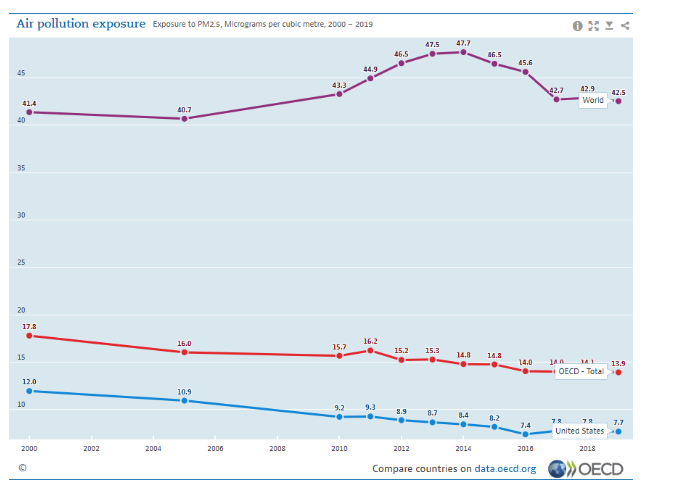

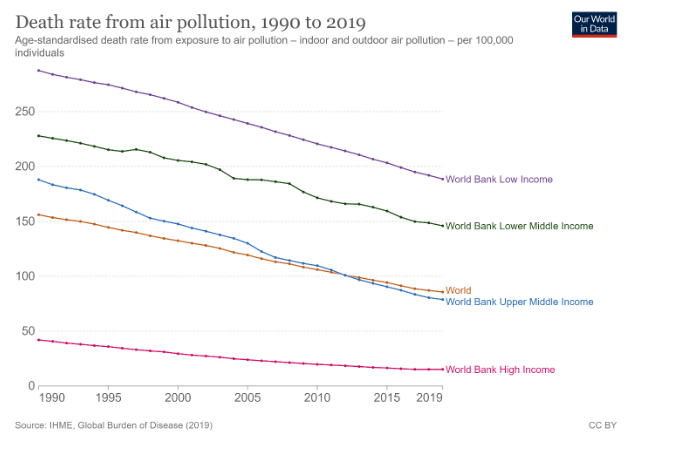

And air pollution has decreased—worldwide more recently and in the developed world (OECD economies) over the longer term—and we’ve seen a pronounced decline in pollution-related deaths pretty much everywhere:

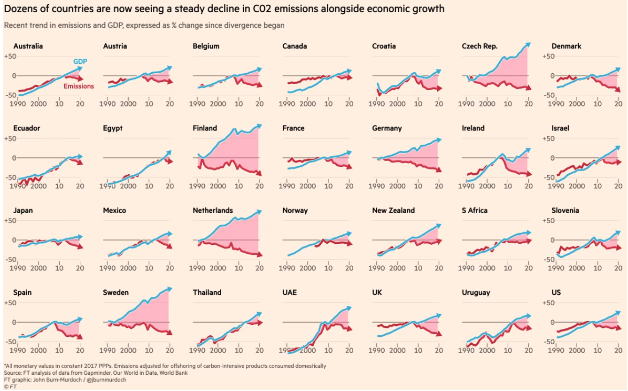

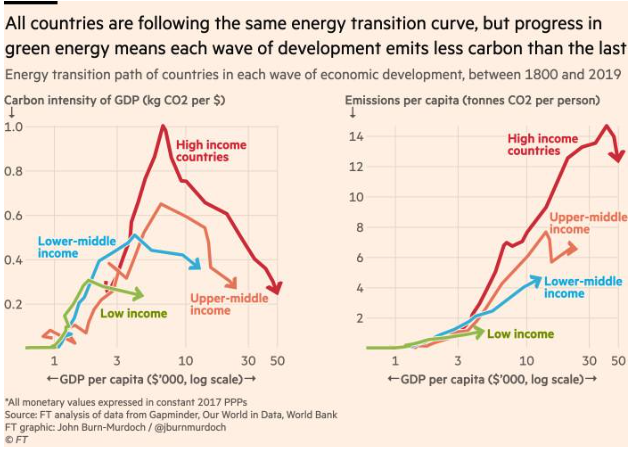

Finally, we’re seeing a major decoupling between economic growth and CO2 emissions in dozens of countries—a process that’s accelerating thanks to new energy technologies:

Thus, the best thing we can do for the planet is to make poor countries rich.

Summing It All Up

One could perhaps be forgiven for predicting planetary doom when the world’s population hit 4 billion back in 1974. Just a few years earlier, the wildly popular eco-pessimist Paul Ehrlich published his bestselling book, The Population Bomb, which famously opened by declaring that “The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” As thoroughly documented in Superabundance, this kind of eco-hysteria was rampant throughout the 1970s, as my two favorite non-Ehrlich quotes in the book hilariously show:

- “Demographers agree almost unanimously on the following grim timetable: by 1975 widespread famines will begin in India; these will spread by 1990 to include all of India, Pakistan, China and the Near East, Africa. By the year 2000, or conceivably sooner, South and Central America will exist under famine conditions…. By the year 2000, thirty years from now, the entire world, with the exception of Western Europe, North America, and Australia, will be in famine.”—North Texas State University Professor Peter Gunter

- “In a decade, urban dwellers will have to wear gas masks to survive air pollution … by 1985 air pollution will have reduced the amount of sunlight reaching earth by one half.”—Life Magazine, January 1970.

More than 52 years have passed since those predictions were made, and they’ve all been proven wrong. Indeed, contrary to the pessimists (back then and now), the 8 billionth human arrived last week to a world that is imperfect, sure, but still far better than the one the 4 billionth found—thanks to the drive and ingenuity of our fellow earthlings. Future challenges remain, but we can and should be confident that they’re conquerable too…as long as we continue to let people conquer them.

Happy Thanksgiving.

Capitolism will be off next week.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.