Dear Capitolisters,

One of the many villains in my new book (which you can now download in full for free) is the classic Washington move of throwing ever-increasing taxpayer money at groups supposedly failed by the “free market,” without any examination of the existing government policies contributing to the problems these folks face. There may be no group getting more such attention these days than American families, with both parties competing to shower them with government goodies—tax credits, childcare subsidies, mandated employer benefits, etc.—to offset ever-rising bills for the things families need. We learned just yesterday, in fact, that these types of policies will be a big focus of the Biden administration’s 2023 economic agenda and the president’s state of the union address. Yet, as my book details in numerous chapters, policymakers routinely ignore the panoply of state, local, and federal policies that restrict Americans’ access to, and thus raise the prices of, all sorts of essential goods and services in the United States, disproportionately harming working families, especially poorer ones, in the process. Today, I’m going to use two such areas—childcare and consumer necessities (food, clothing, etc.)—to show why the most common government solutions to American families’ real challenges usually fall short.

Why Is Childcare So Expensive in Many Places?

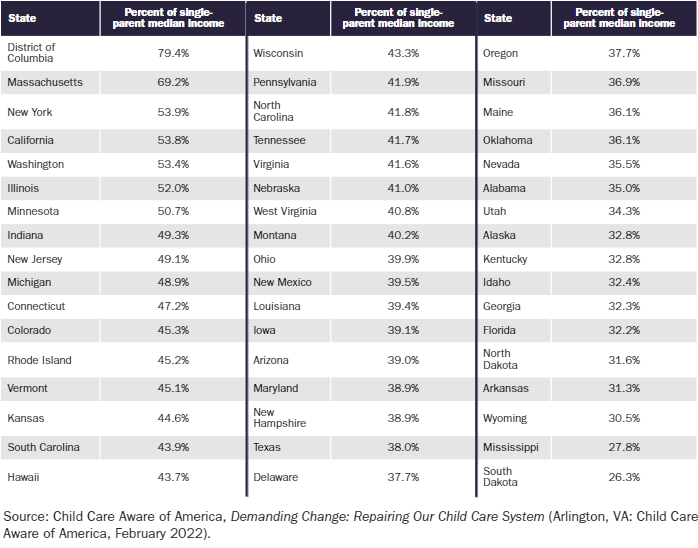

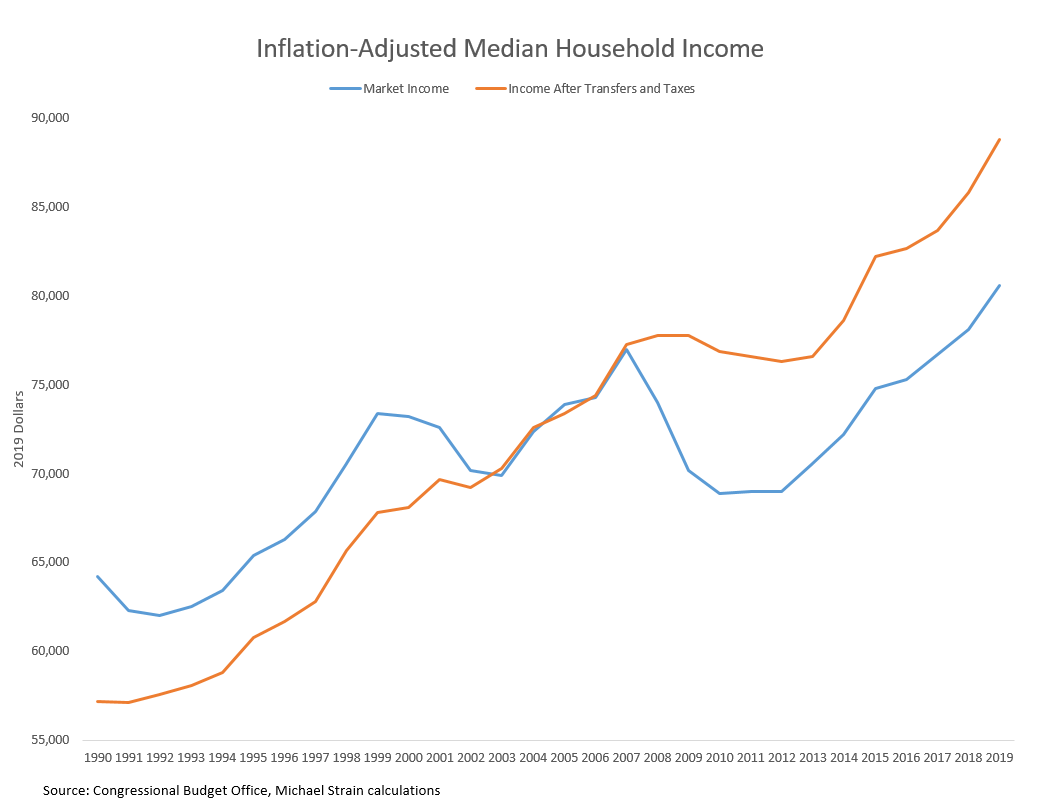

As my Cato colleague Ryan Bourne explains in the book’s childcare chapter, it’s undeniably true that childcare is an ever-increasing burden for many American families—taking up at least 40 percent of a single parent’s median income in many states and thus imposing significant economic harms on workers and their families:

As he explains, some of these price pressures are likely the result of market forces: As Americans get richer, we may demand higher-quality childcare, and the service might also face “Baumol’s cost disease” because it’s a labor‐intensive service that can’t be easily automated.

However, ample research shows that government policy is contributing to the childcare problem in major ways, especially at the state level. This includes:

- Staff‐child ratio requirements. One study from 2015 found that loosening the ratio by just one child across all age groups would reduce center‐based care prices by 9 to 20 percent each year. Earlier research found that allowing a childcare worker to look after only two more kids would reduce prices by 12 percent. Studies also show that these changes have an insignificant effect on the quality of care—i.e., it’s all pain and no gain.

- Occupational licensing requirements. Mandating certain educational or training requirements also increases prices by restricting the pool of potential childcare workers. One study found, for example, that adding a year to childcare center directors’ educational requirements reduced the number of centers in the average market by more than 3 percent. A separate study found that requiring lead providers to have a high school diploma can increase prices by 25 to 46 percent. Many places—such as Washington, D.C., and California—impose much more stringent requirements (e.g., a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education), and, as shown in the table above, they unsurprisingly have some of the highest childcare prices in the country. Unlike staff ratio requirements, these licensing rules do appear to have some effect on the quality of care. However, as Bourne notes, “quality improvements… overwhelmingly occur in just high‐income areas,” while poorer residents simply get reduced access to care. Furthermore, that many states lack these requirements show that they’re more a mandated luxury than a real necessity. (See the occupational licensing chapter for more.)

- Zoning restrictions. Many state and local governments consider home daycares a “problem use” and have thus used zoning restrictions to ban them. This further reduces the supply of childcare in affected neighborhoods, thus increasing prices even more. (This is discussed more generally in the book’s chapter on home businesses.)

Given its role in influencing federal policy and its insanely high childcare prices, the highly regulated Washington, D.C., market deserves special mention. As Bourne noted in the Washington Post earlier this year when lamenting the district’s new licensing restrictions requiring providers have college degrees, “putting two kids into a child-care center in D.C. costs 41 percent more than the local average mortgage payment and nearly twice the cost of tuition at a public university.” That’s undoubtedly a reason why so many Hill staffers and D.C.-based journalists and policy wonks assume a broken national market in need of federal subsidies for childcare. Yet, as the aforementioned studies show, modest changes in state regulation could dramatically increase American parents’ options and lower prices—especially ones in D.C.—by thousands of dollars per year. (Wealthy parents could, of course, choose to pay for gold-plated childcare—governments simply wouldn’t make that the only option.) Such savings could be further boosted by other common-sense policy changes, such as liberalizing immigration to increase the supply of potential childcare workers, au pairs, and babysitters.

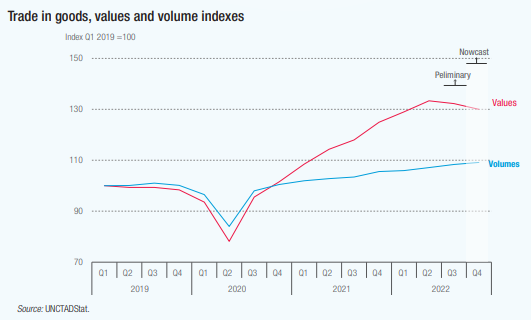

Why Do We Pay More for Essential Goods?

Of course, not every American family needs regular childcare, but they do all need food, clothing, energy, and other essential consumer goods—goods that, as my colleague Gabriela Beaumont-Smith details in her book chapter, are also needlessly inflated by government policy. Let’s start with food—

- Both sugar and dairy products (milk, cheese, ice cream, etc.) are subject to complex systems of subsidies, price controls, and import restrictions that push domestic prices well above world averages and—as we’ve seen with infant formula—cause all sorts of other problems in the U.S. market for these and other, derivative food products.

- The United States imposes high (greater than 10 percent) tariffs and quotas on numerous other foods, including “peanuts, tuna, cantaloupes, apricots, various meats, sardines, spinach, soy‐bean oil, watermelons, carrots, celery, okra, artichokes, sweet corn, Brussels sprouts, cut cauliflower, and so on—costing American importers billions of dollars per year.”

- “Produce marketing orders” let U.S. farmers dictate their commodity’s prices, quality, size, and other factors when sold on the U.S. fresh food market, thus increasing prices of these foods too (and encouraging anti-competitive collusion).

- The Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS), which requires U.S. biofuels to be blended into transportation fuel, raises the price of not only corn‐based products, but also other crops (by taking up finite farmland for corn). According to studies from the Congressional Budget Office and other organizations, “artificial demand for ethanol raises Americans’ total food spending by between 0.8 and 2 percent.”

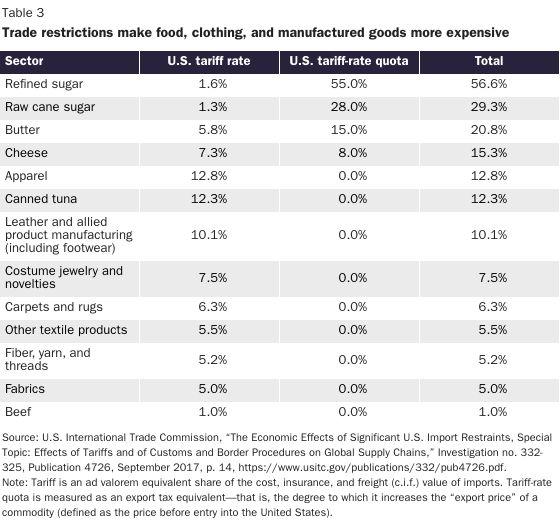

The United States also imposes high taxes on imported clothing and footwear, further increasing prices. And, adding insult to injury, these taxes tend to increase as product quality decreases, thus heightening their impact on poorer Americans who tend to consume cheaper stuff:

Household goods face similar treatment:

Silverware, plates and cups, and drinking glasses are subject to an average tariff of 11 percent, which is almost 16 times the average tariff for all other goods. In fact, tariffs on a small set of home consumer goods made up well over half of all tariff revenue ($144 billion out of $2.33 trillion) as of 2017, even though these goods only make up 6 percent of total imports. Even school supplies are more expensive because of U.S. trade policy. Ballpoint pens and notebooks, for example, are each subject to tariffs of about 10 percent; backpacks and gym bags face 28 percent tariffs.

Nothing says “pro-family” policy like taxes on school supplies, eh? Sigh.

Anyway, studies show that trade policies alone force American households to spend hundreds of extra dollars per year on basic necessities. The U.S. International Trade Commission estimated in 2017, for example, that various U.S. import restrictions raised prices by as much as 56 percent:

A separate study from that same year—before President Trump’s expansive new tariffs were implemented—conservatively estimated that U.S. tariffs cost the median American family around $200 per year via higher import prices. (Higher prices for American-made goods, which usually follow tariff increases, likely increased this tax even more.) Given subsequent tariff actions, this burden is likely even higher today.

Plenty of Other Necessities Too

As Beaumont-Smith notes, other necessities are also affected by various government policies. For example, “tariffs, fuel economy regulations, taxes, maritime restrictions (the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, aka the “Jones Act”), and other policies significantly increase automobile and fuel prices in the United States, thus harming the almost 85 percent of Americans who drove to work prior to the pandemic.” Government policies also increase the cost of energy, beyond just gasoline (including many renewables), and thus further reduce Americans’ real incomes and wealth. All sorts of state restrictions on the provision of medical services—licensing and telehealth restrictions, “certificate of need” laws, etc.—increase U.S. health care costs. And, as we’ve discussed here repeatedly, a wide variety of federal, state, and local policies raise construction and housing prices. I’ll have more to say on these issues in the coming weeks, but for now you can read the book’s chapters on transportation, housing affordability, homeownership (and harmful U.S. housing finance policy), and health care.

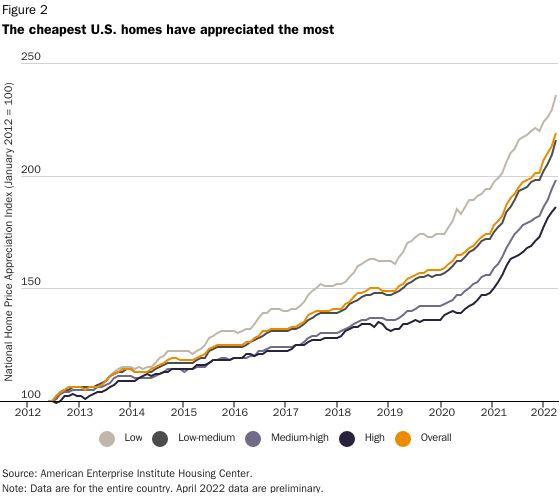

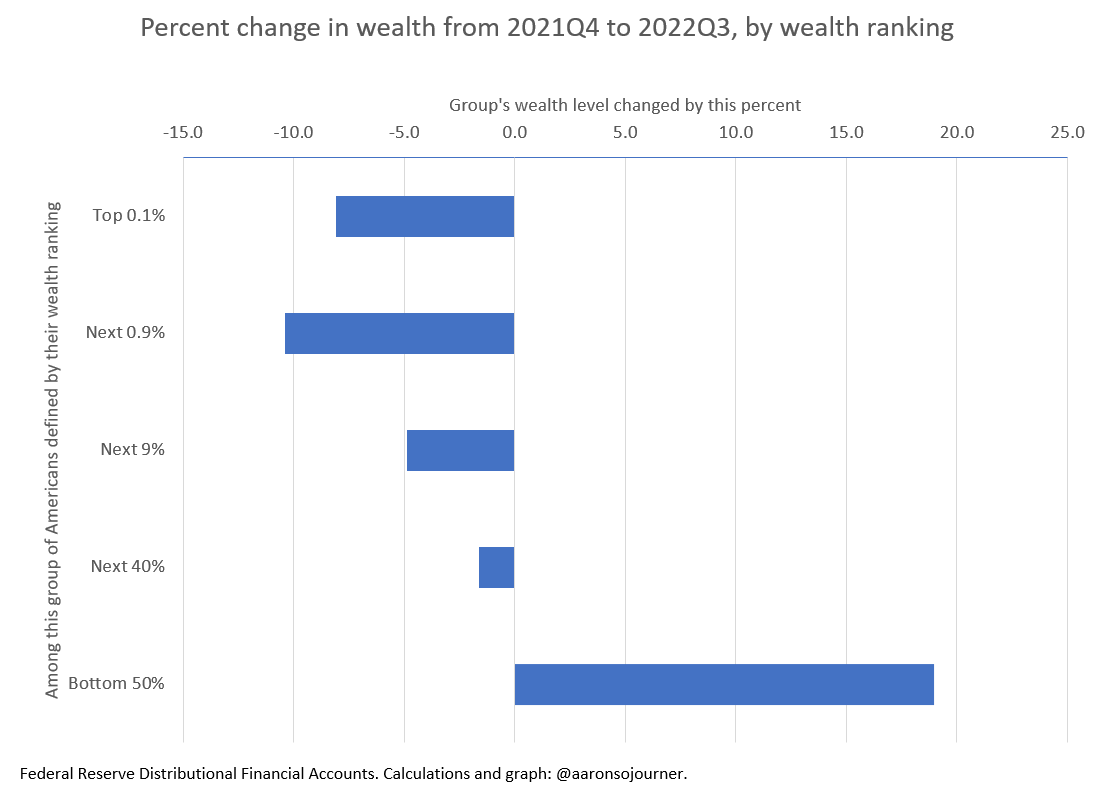

Importantly, these chapters’ authors repeatedly note how the laws and regulations at issue not only increase prices but also disproportionately harm Americans on the lower end of the income scale. Bourne notes, for example, research showing that staff-child ratio regulation “reduces the availability of childcare in lower‐income neighborhoods, making it more difficult for poor families to juggle childcare and work responsibilities while increasing prices, which can then deter other households from moving to that area.” Beaumont-Smith details how U.S. tariffs are highly regressive, meaning poorer Americans’ tariff burden is a much bigger share of their incomes than rich Americans’ burden: “Rising prices of basic necessities are typically a regressive tax on American households, disproportionately hurting workers at the lower end of the wage scale and larger families that consume more, especially ones led by a single parent.” The housing chapter cites research showing “that less‐skilled workers could not afford the higher housing costs in heavily regulated cities that have strong economic opportunities, and so these workers became stuck in lower‐cost areas that had lesser job prospects.” Higher construction costs also can make “starter homes” unprofitable in many parts of the country:

And the chapter on U.S. homeownership shows how federal mortgage subsidies and related policies, which are a global outlier in their intrusiveness, disproportionately fueled home price appreciation at the lowest end of the scale—making those homes less affordable for new, lower-income buyers.

In case after case after case, scores of academic literature and real world experience show how simple reforms to these policies would improve Americans’ living standards and disproportionately benefit big, working class families (who tend to consume more of these necessities than other groups). Yet few in Washington target the supply side and related government policies for reform, choosing instead, as the kids used to say, more demand-side cowbell (all while blaming the “free market” for creating the problem). That might make political sense—especially in the current moment—but it’s surely not a real, long lasting solution. And simply throwing more taxpayer money at these supply-restricted essentials is a surefire recipe for even higher prices, which would then—of course—necessitate even bigger subsidies or even more radical government interventions in the market.

Or maybe that’s the point?

[Capitolism will be off next week. Happy holidays, and see you in 2023.]

Chart(s) of the Week

The Links

Tax policy and U.S. business R&D (NB: Congress didn’t fix this either.)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.