As longtime Capitolism readers probably know, one of the perks of my home gardening fetish is easy access to large quantities of very hot peppers. Back when I started gardening, I quickly discovered that pepper plants are prodigious here in North Carolina. With just a little water and a lot of sun (and deer repellant), a single habanero plant will produce more than 100 peppers from July through the first hard freeze (usually late October). Equip a few whole garden boxes with habaneros, scorpions, ghosts, and other spicy delights, and by early fall you’ll be swimming in capsaicin like Scrooge McDuck swims through gold.

Challenged to creatively dispose of hundreds of peppers each season, I started making hot sauce—for both my personal use and as a Lincicome family Christmas gift for a select group of neighbors and colleagues. Here’s the 2022 batch in progress:

The sauce is, if I do say so myself, pretty excellent—a conclusion many recipients have also confirmed (unsolicited, I promise!). The reviews were so rave, in fact, that they prompted me to daydream of trading in my think tank career for one running a burgeoning hot sauce empire out of my home. On a weekend whim, I even looked into what it would take to start the business—including the regulations governing home-based (“cottage”) food production here in North Carolina.

Needless to say, I won’t be selling my hot sauce any time soon.

Home-Based Food Businesses Face Huge Regulatory Hurdles

Despite remarkable advances in home kitchen technology and the now-decades-old “local foodie” craze, running a cottage food business remains exceedingly difficult in most parts of the country. In a classic case of one’s work and personal worlds colliding, my 2023 book Empowering the New American Worker dedicates a chapter, written by my Cato colleague Chris Edwards, to this very problem. As Edwards explains, the pandemic saw an explosion of home-based entrepreneurship in numerous industries, and food was one of the biggest:

Home-based businesses are critical for entrepreneurship and innovation. Without locating at home, some businesses would not be viable if entrepreneurs had to foot the costs of commercial rent, commuting, and perhaps childcare. This dynamic is evident in the booming cottage food industry (home food production for retail sale), which—as the New York Times recently examined—has benefited from new internet food platforms …

There is no better place for low‐cost product experimentation than an entrepreneur’s home. Homes are low‐cost incubators to test business ideas before larger investments are made. Startups are risky and have high failure rates, so entrepreneurs need early, low‐cost feedback from consumers. Food entrepreneurs, for example, want to test recipes with consumers but may not be able to initially afford commercial kitchen space. Home production can give entrepreneurs the confidence, skills, and capital they need to later open a brick‐and‐mortar location.

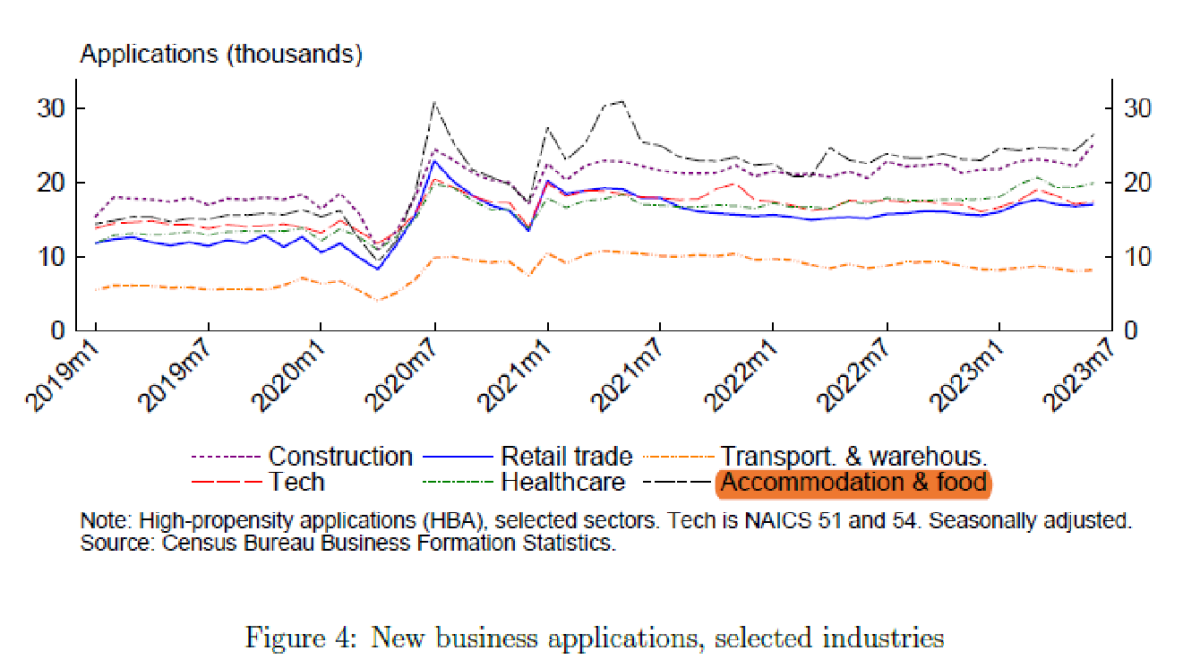

New research from economists Ryan Decker and John Haltiwanger confirm this entrepreneurial trend, with new business applications surging during the early days of the pandemic and remaining elevated—especially in the “accommodation and food” category.

Unfortunately, and as I’ve now learned firsthand, many states and localities make it difficult—if not impossible—to operate a food-related business out of your home.

For starters, as Edwards notes, there are state and local laws that restrict any kind of home-based business. Zoning and related land use regulations, for example, can bar people from operating out of their homes based on the number of employees or visitors, parking availability, exterior appearance, signage, renovations, outdoor activities, materials storage, deliveries, noise, odors, animals, square footage, occupation, and retail sales.

Then there are regulations specific to food-related businesses:

With cottage food…, state and local rules often specify which products can be sold, where they can be sold, and the sales volume allowed. Wyoming allows home businesses to sell just about any type of food that complies with federal laws within an annual sales limit of $250,000. Rhode Island, on the other hand, only allows farmers to sell food made in their homes, and even these farmer sales are restricted in various ways.

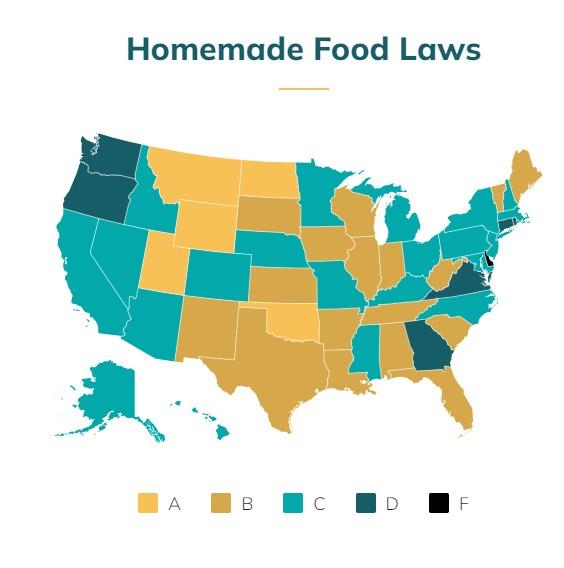

The Institute for Justice’s 2022 report, “Baking Bad,” summarizes each state’s cottage food regulations— on permitted food varieties, food sales (including venue), and business formation—and shows that many states continue to impose heavy burdens on these small businesses. As shown in the IJ report and the following map, my home state of North Carolina is in the middle of the pack overall:

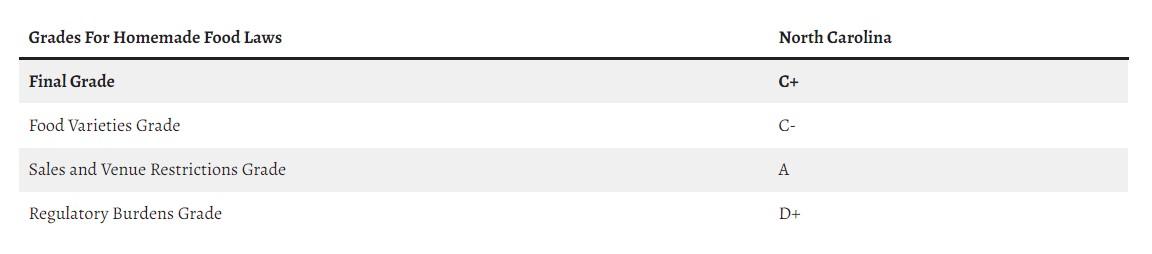

However, digging deeper into the report reveals that the state’s C+ grade is strongly buoyed by an A on sales/venue—once they’re up and running, home food producers can basically sell unlimited quantities of their products in all venues, including mail order and online. The problem is getting up and running. In particular, the state gets a miserable D+ on regulatory burdens—what matters most for starting a business—and a C- on the types of foods that residents can make in their homes:

Here are the gory details:

- Types of food. North Carolina cottage food producers may only sell “low-risk packaged foods” (baked goods, jams, jellies, candies, dried mixes and spices, etc.) and shelf-stable food (pickles, acidified foods, sauces, and some liquids), but the latter requires laboratory testing to confirm its stability. Producers may not sell “high-risk” products, which is basically everything else: fresh, cooked, or frozen meats, vegetables, and fruits; low-acid canned foods; dairy products (including in baked goods); eggs; seafood; bottled water and juice; and more.

- Starting a business. North Carolina cottage food producers must complete a long application process, which includes submitting a detailed business plan, confirming compliance with local permitting and zoning rules, creating state-approved labels (with ingredients, allergens, etc.), and providing a copy of a recent water bill. Applicants must also submit to a home inspection by the North Carolina Department of Agriculture (NCDA). If you use well water, it must be tested prior to inspection. The NCDA tells prospective business owners that it takes at least eight to 12 weeks (but maybe longer) between submitting an application and just getting scheduled for an inspection. Tick tock, tick tock.

- Sales/Venue (Pets). Although North Carolina applies fairly liberal rules on sales, the state prohibits—without exception—cottage food producers from having any pets in the home, regardless of the pet or the kitchen setup.

Wake County, where I live, has even more requirements, as does the federal government. Just recently, for example, local hot sauce producer Benny T’s was forced to issue a “voluntary” (scare quotes intentional) recall of its product after the FDA issued a public warning that the label didn’t specifically list one of its ingredients, wheat, as a potential allergen. As the linked story makes clear, the problematic labels did list “enriched flour” as an ingredient; the company’s recipe hadn’t changed in 15 years; and no one had reported getting sick from the hot sauces. According to the company’s owner, moreover, “up until recently we were not aware, nor told by inspectors, that wheat as an allergen was required to be listed on our packaging,” and “once we were made aware of the issue in late December 2023, we have worked closely with state and federal officials to correct the label.” The FDA nevertheless advised consumers to throw away all jars of the offending sauce.

Let’s hope Benny T’s survives. Sigh.

Stifling Cottage Food Entrepreneurship

FDA shenanigans aside, the state and local restrictions on cottage foods are surely the biggest burden for aspiring food entrepreneurs. Because I’m a dog lover, for example, North Carolina’s pet rule is an effective ban on my hot sauce ambitions, and I’m certainly not alone. In fact, almost 60 percent of North Carolinians own a pet—which is about the same percentage nationwide. The state’s cottage food regulations make us choose between our pets and running a legitimate home business—a choice documented in a recent Reason magazine piece on an anonymous North Carolina baker and her dog Hula:

North Carolina, where the family lives, bans pets in homes used for cottage food production. The state Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services makes no exceptions. Even a goldfish or hamster could turn an otherwise legal business into a criminal enterprise.

The pet prohibition puts Hula’s mom in a bind. She could stop selling cookies, move to another state, or lease space in a commercial kitchen, which would mean driving 30 minutes each way to bake on a fixed schedule while paying thousands of dollars in rent—killing flexibility and profit. The other options are unthinkable. The family could return Hula to the shelter where they rescued her as a puppy. Or they could banish her permanently to the backyard. Hula’s mom refuses. “Your pet is part of your family,” she says. “I don't think it's fair to make me choose between business and family.”

As IJ’s report documents, many states lack this “zero-tolerance” pet policy, and for good reasons. Most obviously, it makes no sense to treat a hamster living two floors from an enclosed kitchen the same as a Persian cat living in an efficiency apartment. (In my case, my dogs are small and hypoallergenic, and I’m literally boiling vinegar.) As discussed below, moreover, the market (producers, consumers, reviewers, etc.) can (and does) sort out responsible producers from irresponsible ones without the need for intrusive, one-size-fits-all regulation that blindly discriminates against more than half the population.

The state’s other cottage food rules establish similar barriers to entry. As one local health regulator recently put it regarding all those “high-risk” foods, “It’s very difficult, if not impossible to get a permit in a residential space from a local health department.” (Sadly, this was said as a warning to local food scofflaws, not an embarrassed admission.)

The regulations’ financial burden can be similarly prohibitive. For example, “shelf-stable” and nutritional label testing at nearby North Carolina State University runs $300 in total ($150 for each test). Business registration costs another $100. And if you make “high-risk” foods, have a pet, or fail (or refuse) your home inspection, you have to use a commercial kitchen/commissary that—as indicated in that Reason piece—costs hundreds, if not thousands, more. This one near me, for example, charges $500 for the application fee, $150 for the membership fee, and $30 an hour for use of the space. It also requires ServSafe food handler certification ($195) and food liability insurance ($400). Ouch.

Even without needing a commissary, the money involved here is significant. One recent survey of almost 800 U.S. cottage food entrepreneurs found that they earned just $2,000 in median annual sales and $500 in median annual profits. They also reported just $500 in median startup capital, mostly financed through personal savings. Here in North Carolina, regulatory costs alone would eat most of that amount—and much more if you’re forced to use a commercial kitchen.

The other burden, of course, is time. In that same survey, half of respondents worked at other jobs either full or part time, while another 15 percent were homemakers. Forcing potential cottage foodies to endure hours of research, paperwork, and inspection prep—plus months waiting for an inspection and for many a long drive to a commercial kitchen—just so they can sell some home-baked cookies (or whatever) will ensure fewer of them take the plunge.

Academic research on this issue is limited but tends to support the chilling effect of regulation on cottage food entrepreneurship—and how deregulation can encourage it. The aforementioned survey, for example, found that there was a “link between entrepreneurial activity in rural communities and the freedom to produce different types of foods,” and that “state laws can inhibit at least some of these businesses from realizing their full potential.” The study’s author thus recommended that lawmakers “look to encouraging the expansion of the cottage food industry as one way to support small-business creation and growth in struggling communities.” Separately, a 2020 study found the implementation of laws liberalizing cottage food restrictions induced a significant increase (between 4 and 11 percent, depending on size) in the number of home bakeries in the United States. A 2021 survey of 136 produce growers in Indiana (which gets a B from IJ in “Baking Bad”) found that, other than simply not having enough time, regulations were the biggest impediment to starting or expanding the production of value-added products in their home kitchens.

This is a shame. As we discussed last year when reviewing The Bear, food is one of the relatively few U.S. industries that has both low barriers to entry and high levels of merit-based mobility. With little more than a kitchen, some ingredients, a good recipe, and hard work, almost anyone can make it. As Edwards notes (and as we’ve discussed), the U.S. craft beer industry is a testament to what can happen if people have the freedom to innovate at home and to profit from doing so:

Homes have also been important for the American craft beer industry, which exploded after home brewing was federally legalized in 1978 and state beer distribution laws were relaxed starting in the 1980s. The number of breweries in America has grown from less than 100 in 1980 to more than 8,300 today. Craft brewing is a $22 billion industry today that grew out of a previously illegal home‐based activity.

As the research above indicates, moreover, the cottage food business is particularly important for women, people with lower incomes, and those living in rural areas. Needless regulation denies them this chance.

And for What?

And it is needless, as IJ’s Erica Smith Ewing explained in 2022 regarding North Carolina’s restrictions:

Regulators defend the rules as necessary to protect public health. Yet cottage food has built-in safeguards. Vendors literally stand behind their products, creating maximum transparency — and maximum incentive to prevent foodborne illness. As cottage-food producers understand, having a personal relationship with customers has more value than mountains of rules and hundreds of pages of regulations.

Corner Farmers Market proves the point. [Market manager Kathy] Newsom ran it for 10 years without a single consumer complaint. When inspectors got involved, the crackdown increased costs without serving any public interest.

Cooks also tend to enjoy eating the stuff we make, further discouraging a lack of care or sanitation regarding home-based food products. And if these incentives still don’t convince you to consume such items, then you’re in luck because nobody’s forcing you to eat it.

Places that have embraced cottage foods aren’t exactly brimming with bacteria, either. In fact, IJ just dug into the seven states that have deregulated their cottage food industries the most—California, Iowa, Montana, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Utah, and Wyoming. Via public records requests with the state agencies responsible for each state’s cottage food program, the organization checked whether these “food freedom” laws had generated incidents of foodborne illness. And they found nothing:

Each of the seven states responded. Not a single state had a confirmed case of a foodborne illness caused by food sold under its homemade food law. In fact, almost none of the states had even a suspected case of foodborne illness for such foods. The only location with suspected cases of foodborne illness was Riverside County, California, that had two suspected cases. But neither case was confirmed. Notably, these cases also did not result in serious illness.

Beer deregulation, Edwards adds, also didn’t significantly boost similar brewing-related incidents. As Smith Ewing succinctly put it, “the government fixed a problem that did not exist.”

Finally, highly regulated states and facilities aren’t immune from foodborne illness problems, which have complicated economic and cultural origins, and onerous regulations can actually be counterproductive by pushing producers to operate illegally. Hula’s dog-mom, for example, refused to submit to state inspection and certification and instead “took her cottage food operation underground.” She still pays taxes and obeys other laws but refuses to give up Hula. That’s good news for the dog, but it’s not great for mom’s business: “She cannot advertise, participate in big community events, or do anything else to draw attention to herself.” Edwards adds that prior to Atlanta easing food regulations in 2012, there were “a lot of home cooks selling baked goods under the table, without licensing or food safety training.” Similar stories have popped up here in North Carolina, too.

Summing It All Up

Whether it’s hot sauce, cookies, casseroles, or cakes, home-based foods are not only delicious but also a great way for many Americans to earn extra money or launch a new career. Yet a messy patchwork of costly regulations, especially at the state and local levels, severely restrict cottage food production and discourage thousands of potential food entrepreneurs for little or no public benefit. For a guy like me who likes to garden and cook and who doesn’t exactly need the extra money, this regulatory blockade is annoying—very annoying—but it’s not the end of the world. I’ll keep making and gifting a few dozen bottles of sauce each year, and that’ll be that. But for the tens of thousands of Americans who are just scraping by or want to escape their workday drudgery, this is a big and needless barrier to a better life—and a blander one for the rest of us, too.

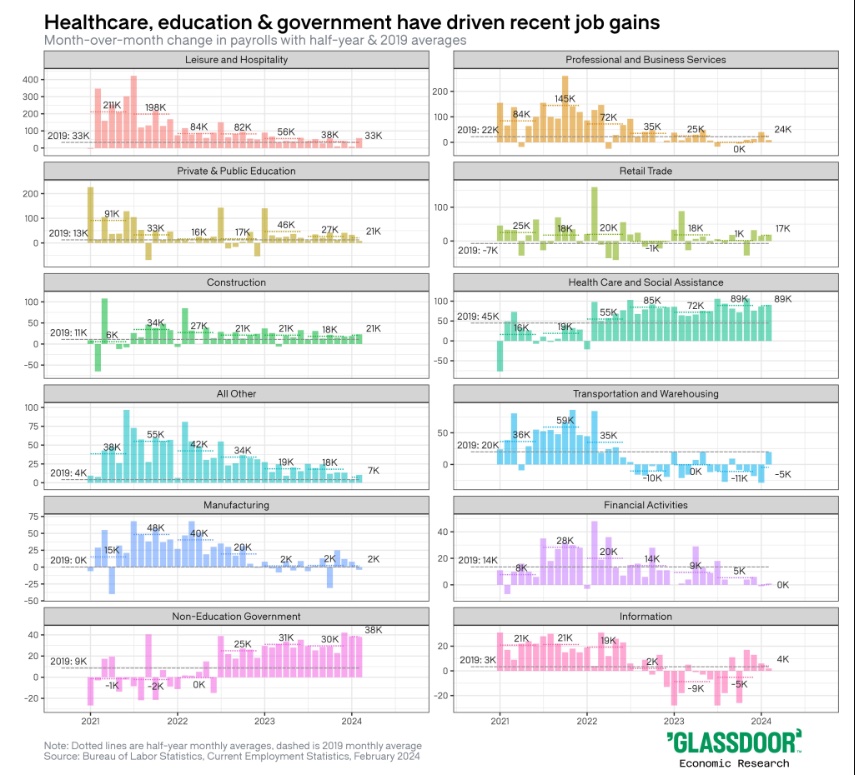

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.