Dear Capitolisters,

My favorite new TV show (yes, it’s clearly summertime) is undoubtedly The Bear, the second season of which just dropped on Hulu. For those who haven’t seen it, the show follows prodigy chef Carmen (Carmy) Berzatto’s return to—and attempt to save—his family’s struggling Chicago sandwich joint following the untimely death of his brother, who used to run the place. As a wannabe foodie with family in the restaurant biz, I find the award-winning show practically irresistible and eerily similar to my (admittedly peripheral) experiences. On the latter point, at least, numerous restaurant pros tend to agree, writing that it’s an accurate representation of the industry’s good, bad, and ugly—no real shock, given that the show’s creator has culinary experience and that several real chefs and restaurants contributed to the production.

Lots of virtual ink has been spilled along those lines since the show debuted last year—and about the show’s incredible soundtrack. But for my money (and since this is technically a newsletter about economic policy), the show’s accuracy extends beyond just the kitchen scenes to the messy, meritocratic dynamism that is running an American restaurant—and many of the policies that make doing so harder than it already is.

(Note: Modest spoilers throughout.)

Culinary Chaos—and Mobility

To be sure, working at a restaurant isn’t all wine and roses: The hours can be long and erratic, starting pay can be low, the work can be grueling (physically and mentally), and the people—well, let’s just say not everyone in the biz is the ideal boss or co-worker. According to the Census Bureau, for example, before the pandemic, “About 75% of workers across all occupations had standard, daytime schedules, compared with 47% of food preparation and serving related workers.” As a result of these and other shortcomings, turnover is high—it’s most definitely not for everyone.

Owning a restaurant can be similarly challenging. Beyond the staff retention issues, competition is fierce; margins are low; both complacency and diner disinterest are ever-present threats; and restaurants’ performance is usually tied to local and national economic conditions that are—as we saw during the pandemic—beyond managers’ and workers’ control. These and other factors contribute to the industry’s well-publicized failure rate.

On the other hand, the industry brings many benefits for those willing to put in the work—and, importantly, regardless of their background. According to the Brookings Institution, for example, the U.S. food service industry has long been both a major entry point for non-college workers and among the industries in which “people gain the skills that enable them to climb the ladder in those sectors.” The industry also features a disproportionate share of minorities, women, immigrants, and ex-cons—many of whom also work their way up to leadership roles. Indeed, food service is commonly cited as among the handful of industries with “great potential” for upward mobility, and the National Restaurant Association estimates that about 90 percent of restaurant managers and 80 percent of owners started out in entry-level positions. As a result, numerous stories abound of chefs, mixologists, managers, owners, and other major players starting on the bottom rung and climbing, often quickly, their way to the top.

That mobility’s owed in part to the industry’s common prioritization of results over credentials – for restaurants and their staff. A nice (expensive) degree from culinary school can open some doors and hone some skills, but the real litmus test is talent, experience, and dedication (just ask these famous chefs). And, while starting and even median compensation often isn’t great, excellence pays off: Top performers—waiters, bartenders, chefs, etc.—can make surprisingly good money, even if they never went to college or end up on TV or a shiny cookbook cover.

Having some family in the biz, I’ve seen this all firsthand: a head waiter who started as a Spanish-only busboy, an award-winning sommelier who dropped out of college and learned wine while waiting tables at a suburban bar & grill, an owner who started as a host, and multiple food trucks that have become packed brick-and-mortar establishments. The work (and the livin’) was hard, and plenty of folks burned out, but for those who could hack it—even ones with sordid pasts or messy presents—the rewards were solid.

The Bear nails this dynamic. Carmy, the show’s protagonist, went from being an insecure, friendless slacker from a troubled home to a self-taught, James Beard award-winning head chef (“CDC”) at one of the country’s best restaurants just a few years later. His second (sous chef) is Sydney, an also-young—but classically trained—Nigerian-American woman living at home with her father after her catering business collapsed. Line cooks Tina and Ebraheim (“Ebra”) are both middle-aged immigrants who weathered the store’s initial chaos and were rewarded with trips to local culinary school (with mixed success). Pastry chef Marcus is another self-taught, impassioned star who was once a small-college linebacker before working at the phone company (and then McDonald’s). Cousin Richie is a foul-mouthed, directionless single dad who finds his hospitality calling after observing the inner workings of a Michelin-starred restaurant. Sister Natalie (“Sugar”) ditches her day job to become project manager (and bureaucratic navigator) for the restaurant’s rebuild. Even goofy friend Neil Fak becomes the in-house (probably unlicensed!) handyman—after being electrocuted a few times.

Surely, some of this meritocracy and development is Hollywood Magic—the likelihood of every Season 1 mainstay moving from the rundown Original Beef to its upscale Season 2 replacement is more than a little fantastical. But the overall theme and feel—a wildly diverse group of people advancing rapidly based on merit and desire—is as real as the show’s endless F-bombs and smoke breaks. Walk into almost any independent American restaurant, and you’ll see the same. It’s quintessential American dynamism in all its Chaos Menu glory.

With the industry’s big rewards, of course, come similarly big risks: Many of the same forces that help a first-generation Mexican immigrant move from kitchen hand to head waiter and then owner undoubtedly also contribute to the aforementioned turnover and failure rate. Unfortunately, public policy can make success even harder—another thing The Bear gets (mostly) right.

How to Block a Business

A running joke about Season 2, in which the gang tries to open the Original Beef’s replacement in just three months’ time, is that the show’s as much about regulation as it is about restaurants. As the folks at Eater recently explained, that’s not really much of a joke:

The Bear still feels eminently accurate when it comes to the often crushing tedium of navigating the world of taxes, permits, and insurance. In what other show about the restaurant industry do we hear about the struggles of getting a fire suppression system to pass inspection, or get an inside glimpse into the absurdity of navigating a mold remediation project? Those aren’t exactly sexy subjects, but they are very real for actual restaurant owners, and The Bear manages to play them both for laughs in a way that actually succeeds.

Indeed it does (and, yes, it’s no surprise why I like the show even more now).

I don’t want to ruin the whole season for you, but this scene in the first episode gives you a good feel for what’s in store the rest of the way—and just how Kafkaesque and daunting the bureaucratic challenge will be:

Sugar: … In other news, I reviewed your numbers.

Carmy: Mm-hmm. And?

Sugar: Aside from being vaguely kinda a little bit sorta close, you’re missing an IRS stipulation.

Carmy: Which IRS stipulation?

Sugar: The one that says businesses have to have all previous debts be current …

Carmy: Yeah, but we’re on a payment plan.

Sugar: … and complete before any new business license is granted.

Carmy: That can’t possibly be true.

Sugar: Here. [shows him paperwork]

Carmy: Alright. So that’s, that’s definitely true.

[immaterial chit chat. Sydney walks in 15 second later]

Sydney: So gas is off until hoods and overheads pass the new fire suppression test.

Carmy: Okay. Is that a [job for handyman] Fak? Sounds like a Fak.

Sydney: No, it is not a Fak. It is not a Fak. It’s a specialist.

Carmy: Aw. Sh-t.

Sydney: Yeah, sh-t. But some good news. Everybody is food certified except for Ebra, who just needs to be renewed. And Richie, who actually has never done it because …

Carmy: Richie.

Sydney: Yes. Also, I filed with the BACP for our City of Chicago Consultant.

Carmy: Right.

Sydney: We need them to approve all of our new business paperwork, and then they’ll send a rep and that rep will sign off on another rep who will come and look at stuff and then sign off on a, on a different rep.

Carmy: How many reps is that?

Sydney: Many. A lot. A lot of reps. Yeah. But it’s-it’s gonna be okay, you know. All we have to do is just stay calm and make sure—

[Sydney falls thru wall]

Carmy: F-ck.

Sydney. F-ck.

Of everything standing in our heroes’ way—the menu, the construction, the staff, the personal stuff—it’s the government that’s their biggest and most omnipresent threat. The crew estimates (optimistically) that just “permits, the inspections, and the licenses” will cost them $10,000, but the bigger cost is time: In seemingly every scene inside the restaurant, their actual work is interrupted by a deflating mention of some new bureaucratic hurdle. Here’s a couple more examples:

“They won’t let me apply for a liquor, beer and wine license without the certificate of occupancy.”

“Uh, the sandwich window can’t open because it isn’t ServSafe certified. It’s gotta be ServSafe certified in order to open. And I don’t know. Ebra didn’t renew his ServSafe certification.”

And on and on.

If anything, The Bear understates the regulatory challenges that aspiring restaurateurs face—especially in a place like Chicago. The aforementioned “ServSafe” stuff, for example, relates to a 2013 state law mandating that all paid staff be certified food handlers—which apparently Ebra and Richie need to be so they can give people sandwiches out a window—and be supervised by a certified food protection manager. That’s not unique to Illinois, but still requires hours of training, passage of a written exam, and as much as a couple hundred bucks in tuition costs, depending on the level at issue (manager versus food handler). Employ uncertified staff, and you get shut down.

More importantly, governments in Illinois and Chicago make it excessively difficult to start or do business. Arizona State University’s Doing Business North America report finds that the city ranks 42rd overall (out of 83 surveyed American localities), 43rd for starting a business, 56th for employing workers, and a miserable 78th for paying taxes. But that’s just for any business; starting a restaurant is far more complex:

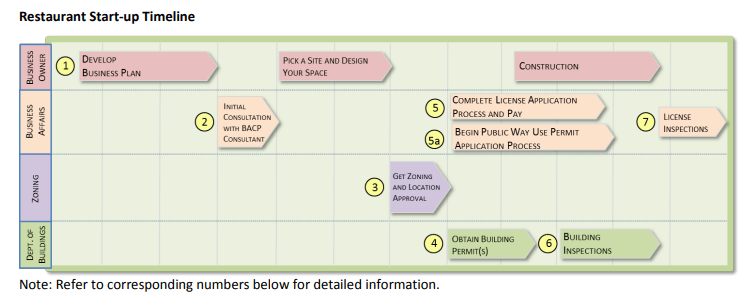

The above diagram really doesn’t do justice to all the steps buried in here. The “initial consultation” (step 2), for example, is actually five steps, including paperwork, sanitation certification, and business registration. Zoning is, as you can imagine, another major ordeal—especially if it involves, as it does in The Bear, construction, booze, and outstanding debts (including traffic tickets!). Overall, Chicago’s “Restaurant Start-Up Guide” is 32 pages of rules, steps, and forms. If you mess up on one, your joint doesn’t open. And applicants can fail inspections not merely for lacking adequate equipment or sanitation, but if—for example—the exit door has “improper swing,” if construction plans aren’t stamped, if the restaurant layout doesn’t match the approved floor plan, or if you have the wrong kind of sink.

Yes, sink.

Believe it or not, this morass is actually the improved process—as my Cato colleague Chris Edwards documented in 2021 when examining how state and local regulations stifle American entrepreneurship:

When he was mayor of Chicago, Rahm Emmanuel tackled excessive regulations on small businesses and startups. He found that the city imposed 117 types of business licenses compared to just 40 in Phoenix. In Chicago, “if a restaurant wanted to have patio seating and serve late night drinks, there were separate processes for zoning, late license hours, liquor license hours, health inspections, and construction permits.” The mayor pushed through reforms in 2012 that reduced the number of business licenses to 49.

However, Emmanuel did not go far enough. In 2019, a Chicago alderman complained that “just about anything you want to do in Chicago comes with some kind of permit or license attached.… [But] many parts of the city’s regulatory processes are mired in paper‐only applications, in‐person meetings at downtown offices (during work hours, on weekdays), and subsections of city departments with no publicly listed director or other staff contact that a constituent could reach out to with questions.” The problem, he said, is that “complexity comes with a real cost in terms of businesses that never open.”

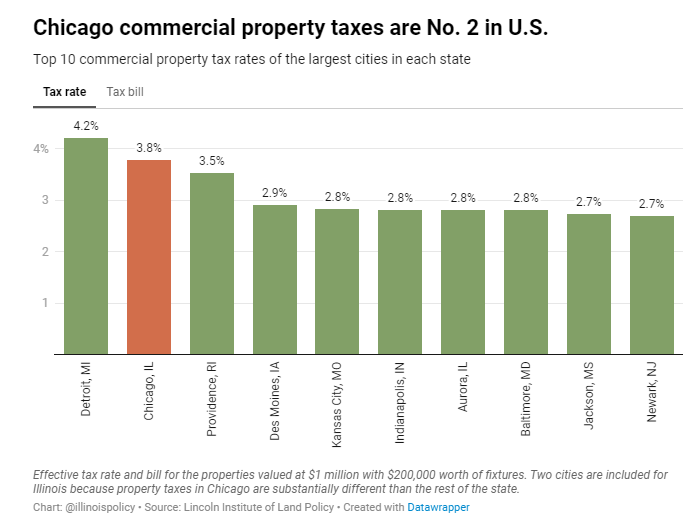

Local taxes are even worse. According to the Tax Foundation, Illinois ranked 44th (seventh-worst) in the nation in 2022 total tax burden and 36th for the overall state business tax climate. (It was even worse in several key areas.) Chicago then kicks it up another notch: It has the country’s second-highest sales taxes and second-highest second highest commercial property taxes*:

(*The property in The Bear was valued at around $2 million.)

According to the Illinois Policy Institute, “Chicago’s 911 surcharge, wireless taxes, amusement tax, soft drink tax, bottled water tax, cigarette tax, parking tax, ride-sharing and home-sharing fees were among the highest among other large U.S. cities as recently as 2018.” Overall, it’s one of the most taxed cities in the country.

Tax and regulatory burdens have encouraged many large, cash-rich companies—Tyson Foods, Boeing, Caterpillar, and Citadel—to flee Chicago in recent years. Penny-pinching entrepreneurs don’t stand a chance.

As Edwards explains (and as The Bear shows), these costs—both money and time—not only inhibit business formation, but also have other unintended consequences. For example, research finds a strong connection between regulation and corruption: In short, as the number of inspections, licenses, and permits grows, so do the bribes (and the people asking for them). Chicago, of course, has a long and storied history of government corruption, and—as Edwards explains—it’s often linked to local bureaucracy:

Corruption scandals in Chicago often stem from bribes for licenses and permits. The system of “alderman privilege” puts city council members in a position to approve or block regulatory actions within their wards. An entrepreneur who needs permits and licenses to start a pizzeria may be out of luck if it is near an existing pizzeria favored by an alderman. Aldermen “have de facto veto power over any new building within the ward they represent. In other words, if you want to build within a ward, you need to convince that alderman to approve of it. If they do not want it built, it will not be built.… Aldermanic privilege creates near‐insurmountable inertia, and only benefits people with entrenched interests.”

University of Illinois at Chicago experts reviewed Illinois and Chicago corruption cases over recent decades and found: “All of the governors and 26 of the aldermen were guilty of bribery, extortion, conspiracy or tax fraud involving schemes to extract bribes from builders, developers, business owners or those seeking to do business with the city or state. The bribe‐payers either assumed or were told that payment was necessary to receive zoning changes, building permits or similar city or state action.… At the heart of most convictions is a payoff for something that is a sweetheart contract or a law or permit necessary to do business. This has been the main pattern of corruption in the city and the state for over 150 years.”

George Ryan, the Illinois governor from 1999 to 2003, “was found guilty in 2006 of racketeering, conspiracy and numerous other charges. Many of the charges were part of a huge scandal, later called ‘Licenses for Bribes,’ which resulted in the conviction of more than 40 state workers and private citizens.”

Corruption is costly and unethical, but some studies show that it can actually facilitate entrepreneurship by “greasing the wheels” of the regulatory process—especially in places that have lots of bureaucracy. And we see exactly this in The Bear, as the team asks Uncle Jimmy—who may or may not be mobbed up (but probably is?)—to help them get one particularly troublesome permit.

Thanks to Jimmy’s help and a few other last-second saves, the new restaurant opens in the nick of time. That outcome makes for entertaining TV, but—as many budding entrepreneurs unfortunately know all too well—it’s probably one of the show’s least accurate parts.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.