Dear Capitolisters,

If recent reports are to be believed, it’s tough out there for Team America right now, especially in its ongoing clash (ahem, competition) with China. Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers kicked off the worrying a couple weeks ago when he cautioned that, based on his recent discussions with various foreign officials about U.S.-China economic “fragmentation,” many developing countries are choosing to “fragment” with Beijing:

Somebody from a developing country said to me, ‘what we get from China is an airport. What we get from the United States is a lecture,’…. We are on the right side of history—with our commitment to democracy, with our resistance to aggression in Russia… But it’s looking a bit lonely on the right side of history, as those who seem much less on the right side of history are increasingly banding together in a whole range of structures.

Others have voiced similar concerns about waning U.S. popularity abroad, pointing to various events and international meetings at which American diplomats feel sidelined and “powerless.”

For the record, conclusions about whether the United States is “popular” (or whatever) abroad—and how important such “popularity” is for U.S. interests—are subjective, fluid, and complex. It’s far more shades of gray than it is black and white or some binary “Team America vs. Team China” choice. Nevertheless, two things about this complicated situation remain undoubtedly true: First, there are some unwelcome signs that large and geographically (if not economically) important developing countries are, if not choosing China over the United States, at least hedging their bets and shrugging off core U.S. geopolitical priorities. And, second, the United States government is foolishly giving them plenty of reasons to do so.

Not So Team America

In just the last few weeks, in fact, there have been several reports of foreign leaders basically telling the U.S. to go pound sand—and usually embracing China in the process:

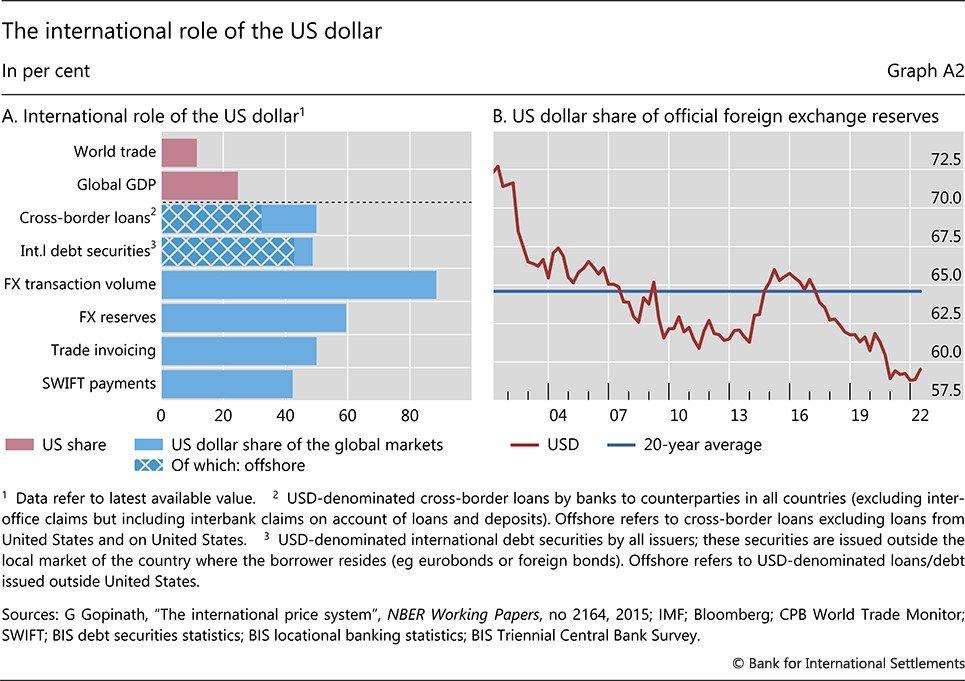

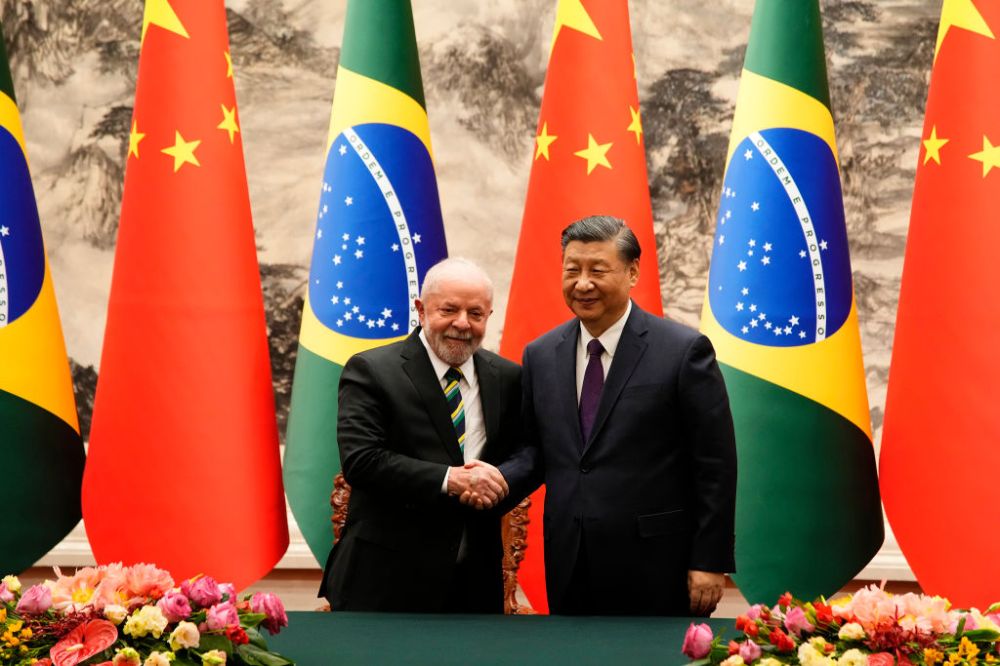

- During Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s three-day visit to China, he not only signed more than a dozen bilateral accords (worth about $10 billion), but also vowed to work with Chinese President Xi Jinping to “balance world geopolitics” and suggested that the developing countries “come up with an alternative currency to the dollar for use in trade between them.” Then, he “struck a further note of defiance against Washington in another speech given alongside [his “good friend”] Xi, during which Lula noted he had visited the Chinese telecom company Huawei, which is subject to US sanctions.”

- A few days before Lula’s visit to Beijing, Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim was there doing much the same thing (albeit more quietly): During his four-day stint, “19 agreements were signed to boost investments in green technology, digital economy and modern agriculture.” The meetings also signaled “the importance of China to Kuala Lumpur’s foreign policy framework” and underscored China’s strong economic ties to Malaysia: “China has been Malaysia’s top trading partner for 14 years running and was also the biggest source of foreign direct investment in 2022 at US$12.5 billion (S$16.7 billion), nearly double that of the United States in the second place.”

- According to James Crabtree, executive director of the International Institute for Strategic Studies Asia, Anwar’s visit is par for the recent course for developing countries in China’s orbit: “Asian nations from Bangladesh and Indonesia to Malaysia and Thailand view China as central to their economic future. Rather than decoupling, they seek more trade with Beijing.” Vietnam, he notes, is also on this list: “Its bilateral trade with China has rocketed in recent years, with similar patterns discernible in the rest of what is sometimes called ‘factory Asia.’”

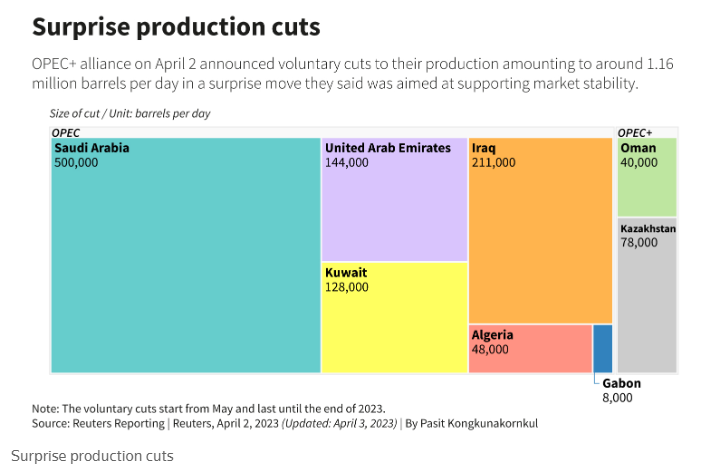

- Finally, there’s the Middle East, where OPEC oil producers earlier this month “announced further oil output cuts of around 1.16 million barrels per day, in a surprise move that analysts said would increase prices and that the United States called inadvisable”; where Saudi Arabia and China have explored invoicing oil sales in yuan (in part to avoid the threat of U.S. sanctions); and where Saudi Arabia last month announced a surprise “détente” with Iran (which is still subject to U.S. sanctions) that was hosted by Beijing and “prompted questions about U.S. leadership” in the region.

Despite what the Biden administration and its domestic cheerleaders would have you believe, none of this screams “America is BACK, baby!”

Washington’s Bad Parenting

As the Financial Times’ Alan Beattie smartly notes regarding Lula’s comments, these actions do not mean that Brazil has suddenly “joined a Chinese geopolitical camp and abandoned the US and the EU.” And the same goes for the other countries mentioned above and many others (e.g., in Africa). The United States remains a very attractive market with a lot of great global companies and people, and our government and culture have earned a lot of global goodwill. Team America’s laurels can still support a lot of weight.

But it’s also undeniable that, in terms of both recent and historic policy, the U.S. government isn’t doing itself or its diplomats any favors in the developing world and is in several ways actively antagonizing the very countries it would need in any “Great Power Competition” with China. Combined with the aforementioned U.S. “lectures,” it’s a bad case of “do as I say not as I do” foreign policy—and it’s generating predictable “rebellious teenager” results.

Start with just the recent actions:

Most obviously, the United States has implemented three new industrial policy laws—the bipartisan infrastructure law, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the IRA—that are replete with beggar-thy-neighbor “Buy American” protectionism that openly encourages multinational corporations to divert their dollars away from foreign markets, especially in Asia, and towards the United States. Beattie helpfully how some of this industrial policy will affect Brazil:

The US and Europe have traditionally been by far the biggest sources of [foreign direct investment] into Brazil, but Biden’s policy in the US in particular is in favour of reshoring, or trading with a small number of trusted trading partners, rather than producing overseas. While GM has a big presence in Brazil, for example, Ford shut down all car production there in 2021 and is concentrating on producing electric vehicles in the US.

And, even when not being outright protectionist, various anti-China “friendshoring” initiatives and restrictions—such as the IRA subsidy requirement that EV battery minerals be sourced from “free trade agreement” countries—will likely exclude developing countries like Indonesia (which has a lot of those minerals but also does a lot of business with China).

The United States still imposes bogus “national security” tariffs on steel (25 percent) and aluminum (10 percent) from almost every country in the world, including all the ones mentioned above—many of whom are significant steel producers and have long complained about the taxes. In fact, while certain developed country allies (Japan, the EU, the U.K.) have secured slightly better import terms—“tariff rate quotas” (reduced duties on specified quantities of the metals)—under the Biden administration, developing Brazil and Argentina (and South Korea) are stuck with Trump-era hard quotas that are in key respects worse than the tariffs (and especially worse than the TRQs) because they cap import volumes regardless of market conditions.

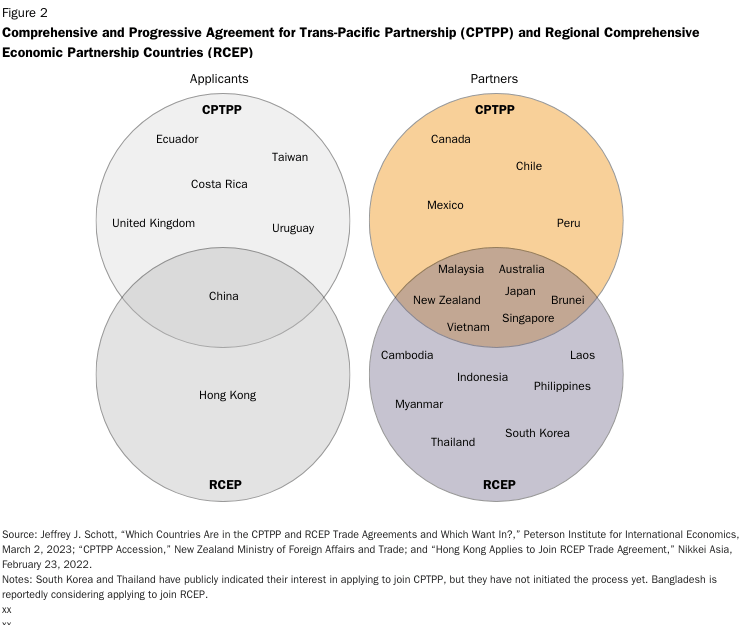

The United States abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership (now the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership), which already includes Malaysia, Vietnam, and Brunei and to which Ecuador, Uruguay, Taiwan and (maybe) Thailand are acceding. The Biden administration also has refused to initiate new free trade agreement negotiations or even continue Trump-era ones (e.g., with Kenya), choosing instead less-ambitious talks that don’t involve Congress—even as developing countries, allies, and U.S. diplomats beg for more ambitious and long-lasting economic engagement. Beattie again shows how this affects U.S.-Brazil relations: “The US’s aversion to signing any new trade deals will handicap Brazil’s attempts to mesh with supply networks aimed at the American market — certainly compared with a country like Mexico, which has privileged access through the US-Mexico-Canada trade pact.”

China, by contrast, has not only concluded its own CPTPP-competitor agreement, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, but is also trying to join the CPTPP and is negotiating other FTAs too—maybe even one with Brazil and other members of the Southern Common Market (aka “Mercosur”).

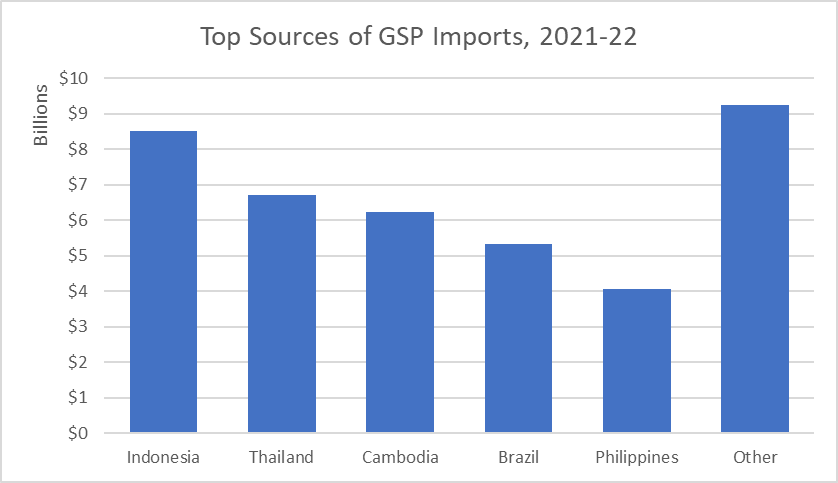

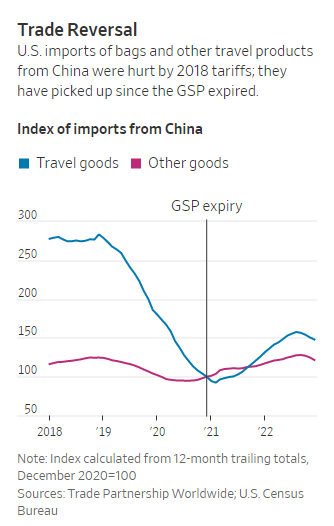

The United States also has failed to reauthorize the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), which expired in December 2020 (despite enjoying broad bipartisan support) and provides limited duty-free access to the U.S. market for imports from non-China developing countries. The program isn’t perfect—mainly because it’s not ambitious enough—but has nevertheless been a lifeline for many developing country exporters and is thus today a major irritant for affected governments. When it expired, the Wall Street Journal reported last month, “119 developing countries and territories, including Thailand, Brazil, the Philippines, Indonesia and Cambodia, that had been eligible for duty-free import to the U.S. were hit with tariffs.” Data from the good folks at the Coalition for GSP show that these new tariffs have conservatively hit more than $40 billion in imports during the two years since GSP expired—imports from many of the countries that the United States has tried to promote as China manufacturing alternatives:

Without GSP, the Journal explains, “U.S. importers had to choose between hiking prices for consumers, absorbing the hit through lower profit or finding a cheaper place to manufacture.” And that “cheaper place,” it turns out, has been the very Chinese mainland that they recently left, thus “denting investment in countries that show promise as alternatives for manufacturing outside China’s vast factory floor.”

Oops.

The United States also has marginalized the World Trade Organization’s negotiating arm, refused to follow its rules, and singlehandedly neutered its dispute settlement body, all of which help developing countries act as equals to big players like the United States and China. (See, for example, dispute victories by Brazil and four African nations on U.S. cotton subsidies, by Antigua on U.S. internet gambling restrictions, and by numerous developing countries on U.S. anti-dumping actions.) It’s no wonder, then, that Chinese Premier Li Quiang stressed after meeting Lula that “both China and Brazil are defenders of multilateralism” and will work to “advance WTO reforms in the right direction.” (He also mentioned “trade” three times in four paragraphs. Coincidence, I’m sure.)

There are also increasing rumblings that well-intentioned-but-ambiguous U.S. regulations blocking imports made from “forced labor” (which, as we’ve discussed, can be defined well beyond what we commonly think of) are being increasingly abused for protectionist ends against non-China developing countries. Under the regulations, for example, any anonymous schlub with “reasonable evidence” of a violation can alert Customs, which can then block imports without disclosing a basis for the decision and leave them blocked until importers prove the negative, i.e., that they didn’t do what was alleged. (“What that means is the U.S. importer must collect documentation sufficient to persuade a CBP import specialist the imported product was in no way made or processed with any forced labor.”) Meanwhile, U.S. envoys go overseas and lecture their foreign counterparts about these guilty-until-proven-innocent violations. That can’t be enjoyable.

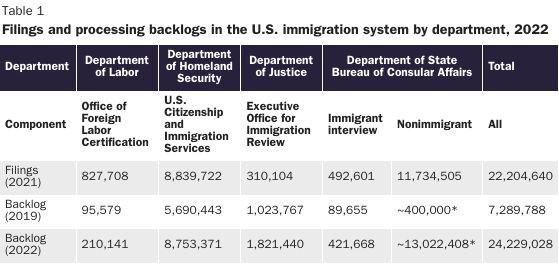

And, finally, we continue to suffer from a wide range of immigration-related problems, such as our insane visa backlogs (24 million pending requests as of last year) and consulate problems (“Many consulates take more than a year to schedule tourists, visitors, and business travelers for interview appointments”). The problem is especially bad for Indians seeking permanent resident status: “about 215,000 petitions will expire as a result of the death of the immigrant before the immigrant receives a green card, and more than 99 percent of these deaths will be Indians.”

These relatively new international irritants come on top of the historical ones, such as:

- High “regular” tariffs and restrictions on many goods in which developing countries often have a comparative advantage (e.g., because the items are labor intensive) and are therefore essential for their development. This includes sugar and canned tuna, as well as textiles and apparel, footwear, and other mass market goods:

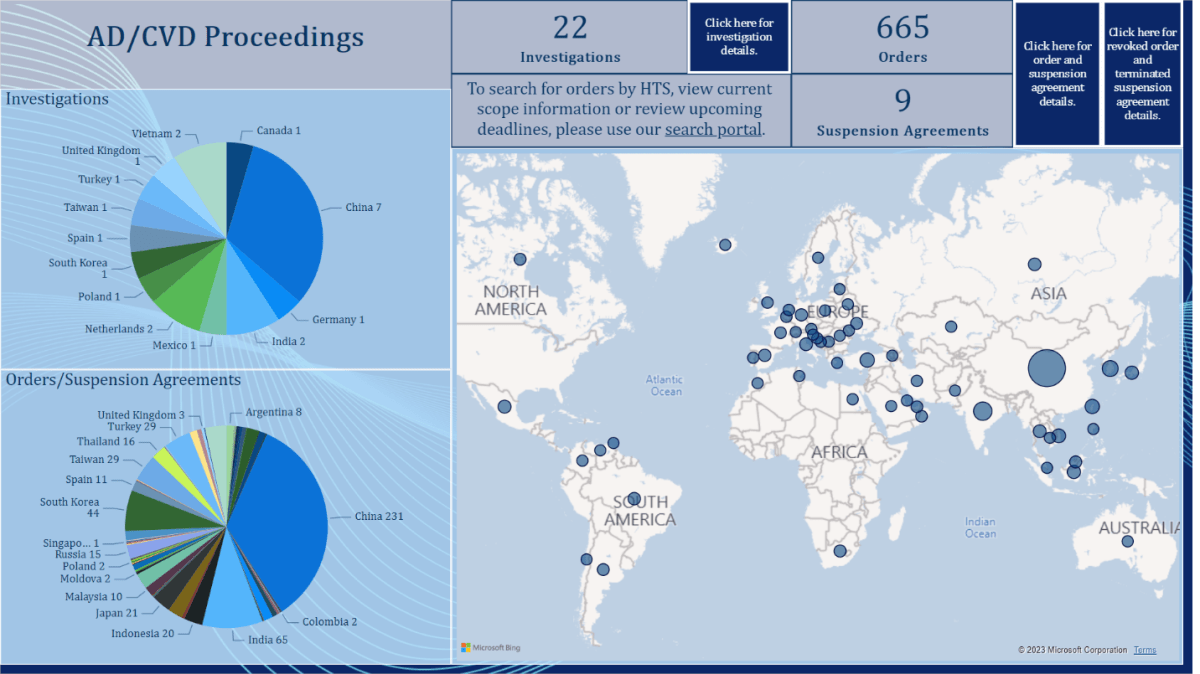

- Hundreds of “trade remedy” duties on imports from developing countries, pursuant to—as we’ve discussed—laws and methodologies that all but ensure that these duties are high, and that they remain in place for years, if not decades. (Hence, why we have all those WTO challenges.)

- Massive and unending farm subsidies, which, as I explained back in 2020, hurt less productive developing country farmers by lowering world prices to levels at which they can’t compete, and by lowering U.S. prices and thus acting as a “non-tariff” barrier to more expensive imports of food and feed. Thus, “Cutting U.S. farm subsidies would thus help some of the poorest people and regions in the world (especially since agriculture historically plays a foundational role in their economic development).”

The list goes on (and on).

Summing It All Up

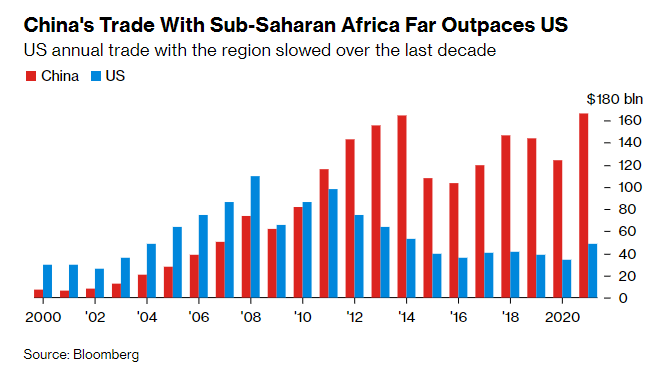

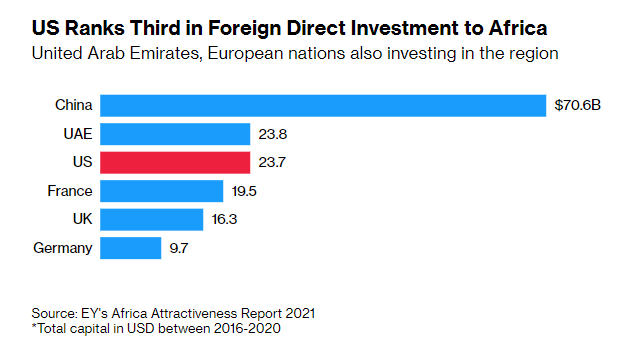

As noted, the United States still has a lot of things going for it in any great geopolitical showdown (or whatever) with China—including many non-economic factors and foreign countries’ strategic self-interest in playing both sides of the rivalry. But it’s undeniably true that one of America’s longstanding global advantages has been our economic openness and engagement abroad, and that China’s gravitational pull has increased in recent years—and in key locations. Consider, for example, these recent charts on Africa:

And this one on many others:

Some of these trends are unavoidable because of the size of China’s economy and its proximity to various Asia-Pacific economies (what we nerds call the “gravity model” of trade). But, as Summers noted in a subsequent interview, the relatively recent and more protectionist shift in U.S. policy still deserves some—if not much—of the blame:

Indeed, as economist Scott Sumner explains, the shift is actually worse when put into broader historical context:

Over the past 4 decades, many if not most of our “lectures” have been US officials arrogantly telling less developed nations (and even developed places) that they needed to follow the “Washington Consensus”. You remember the Washington Consensus, the idea that countries should refrain from protectionism and industrial policies.

Now the US has abandoned the Washington Consensus and decided to go all in with protectionism and industrial policy. And that’s because we supposedly need to do this to keep from falling behind. But weren’t we told that these policies slow economic development.

The United States wasn’t perfect during those four decades of supposed “Washington Consensus,” but it’s recently dialed the hypocrisy up to 11, with both parties seemingly on board with the inevitable (bad) geopolitical results. As the FT’s Edward Luce notes, this new “Washington Consensus” is “as pessimistic as the old one was optimistic” and “less intuitively American than what it replaced.” Will it be as effective as the old consensus, which was—contra the myths—pretty darn effective in plenty of ways? It’s too early to say for sure (though I of course remain skeptical), but the initial returns aren’t promising.

Chart of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.