Dear Capitolisters,

As you’ve probably noticed, things are getting more expensive out there. (I, for example, thought I might need to take out a loan to pay for my last trip to Costco.) What was once supposed to be a short spike in consumer prices—tied to economic reopening and pandemic-related shortages—has persisted for much longer than most policymakers expected and thus turned into a major economic and political story. It’s also sparked an increasingly heated debate among economists about what caused the current bout of inflation and whether it’s the new U.S. normal or just “transitory.” I, for one, tend to think it’s more likely the latter, but this honestly misses the point—about the risks now out there and the broader lessons that the current moment can teach us about U.S. economic policy.

Rhetoric Meets Reality

Regardless of whether you think inflation is temporary or longer-lasting, there’s little doubt that U.S. policymakers have repeatedly been too sanguine about how hot prices would get, how broad these price pressures would be, and how long they would stay that way. The Federal Reserve, for example, projected in March that its preferred measure of inflation, the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) index, would hit 2.4 percent for full-year 2021. And that same spring, various Fed officials and other economists told us that “transitory” price pressures would abate by the summer as supply adjusted and workers returned. Shortly thereafter, however, the Fed upped its 2021 PCE forecast to 3.4 percent, while Chairman Jerome Powell even in August maintained his view that recent spikes—in things like used cars—were isolated and abating, and thus that broader inflationary pressures were contained.

In late September, however, the Fed again raised its 2021 PCE forecast, this time to 4.2 percent—indicating, once again, more significant and persistent price pressures than earlier forecasts. They haven’t yet updated the September figures, but professional forecasters surveyed by the Philly Fed on Monday now see the 2021 PCE index coming in at 4.9 percent—another large upward revision.

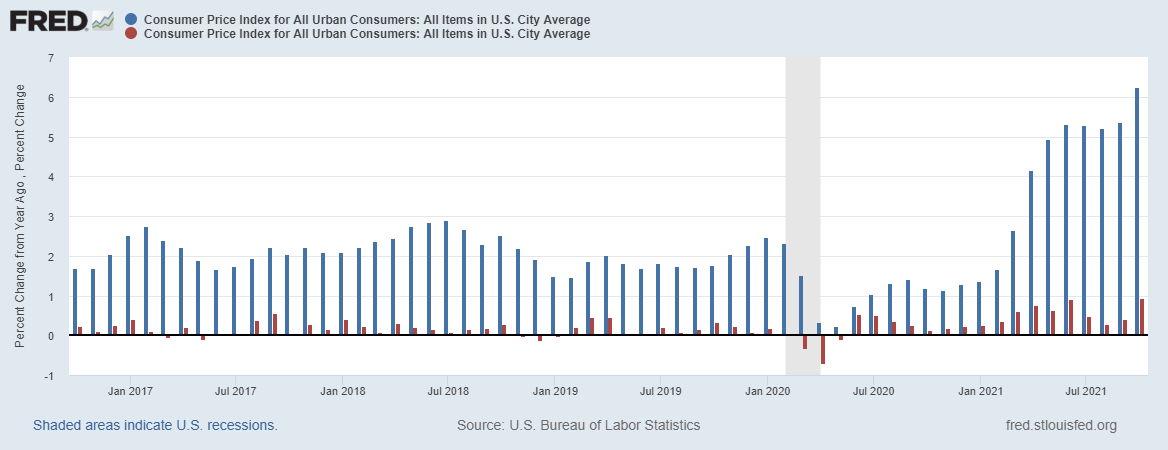

Given the new data from a separate inflation gauge, the consumer price index (CPI), it’s easy to see why. Although year-over-year data (blue lines below) showing “record” CPI prints suffer from “base effects” because inflation was basically negative when the pandemic first hit, the monthly data (red lines) justify renewed concern. For example, in the four years preceding the pandemic, monthly CPI gains averaged about 0.2 percent. Since April of this year, however, the average has more than tripled at a little over 0.6 percent per month, and the late-summer CPI swoon that had “Team Transitory” taking a victory lap has disappeared.

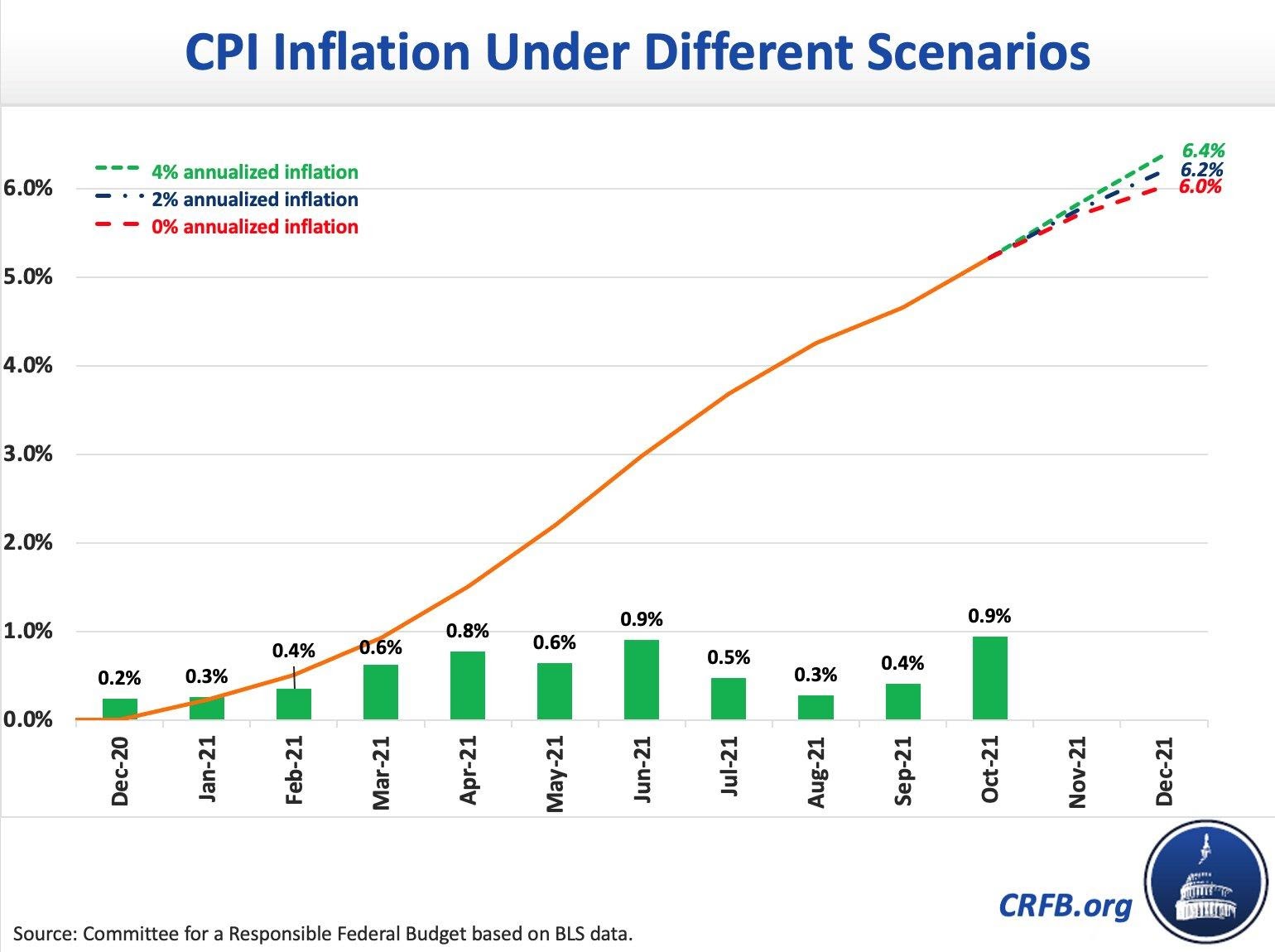

As helpfully calculated by CFRB’s Marc Goldwein, we’re now looking at full-year 2021 CPI growth to clock in at more than 6 percent—again well above where basically anyone on Team Transitory thought we’d be in March or April of this year:

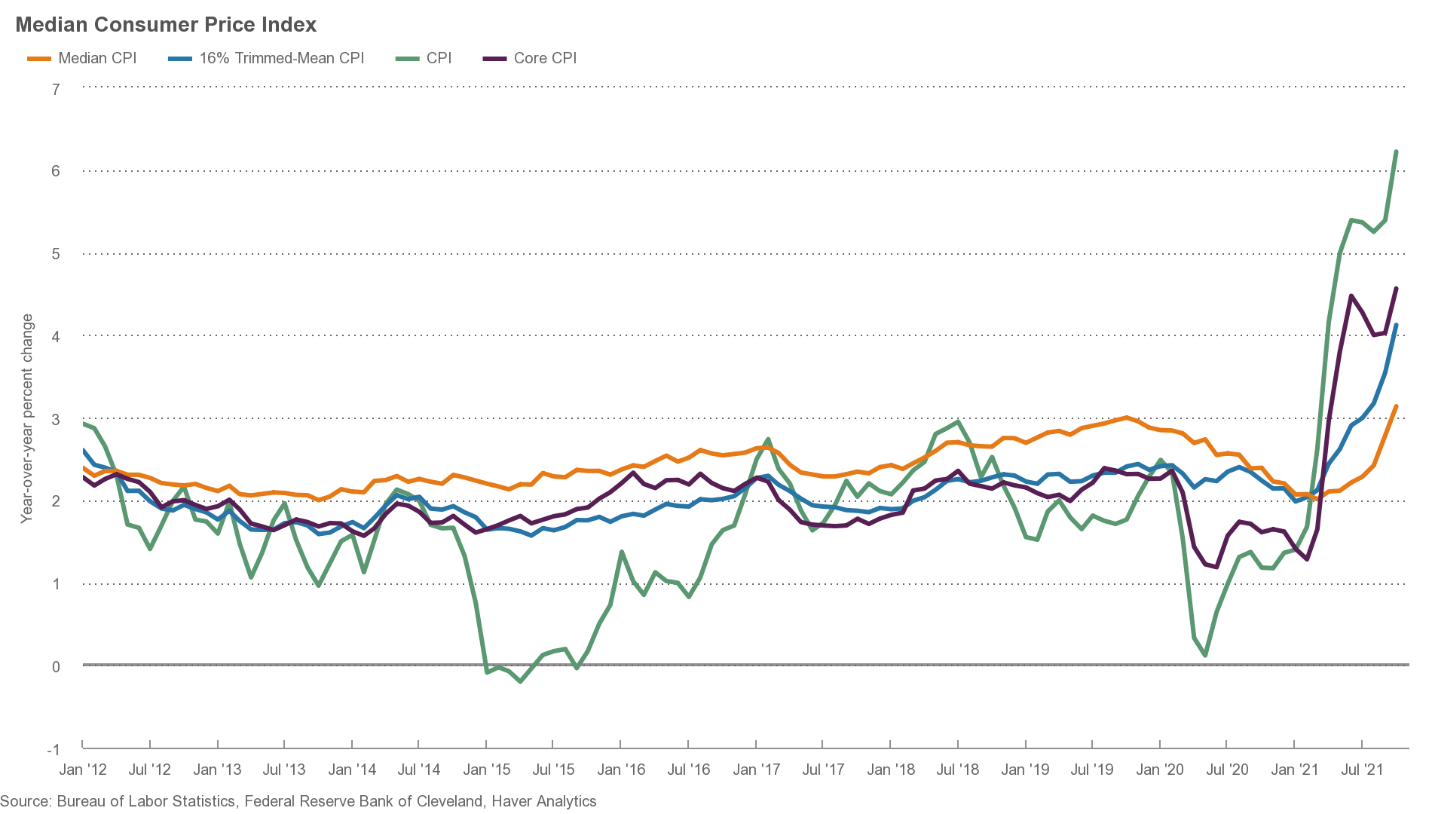

Furthermore, price increases aren’t isolated like Powell and others predicted this summer. As explained in a recent Reuters piece, for example, alternate CPI measures from the Cleveland Fed that are intended to account for volatile items (gas, food, etc.) or isolated factors (hotels, rental cars, etc.) are also showing significant and persistent upticks and even a little acceleration this fFall:

Median CPI—an alternative measure that many economists like because it trims the highest and lowest figures—now annualizes at 5.1 percent for 2021 because price increases have broadened out:

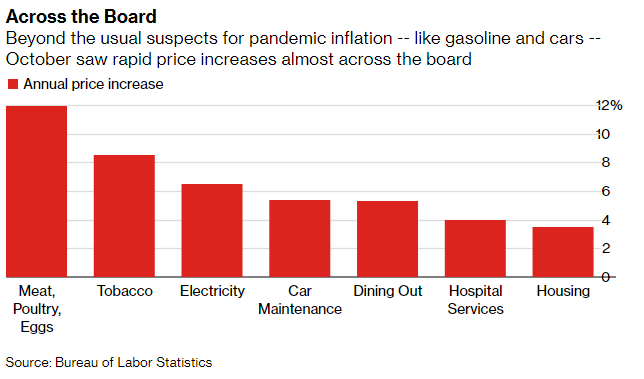

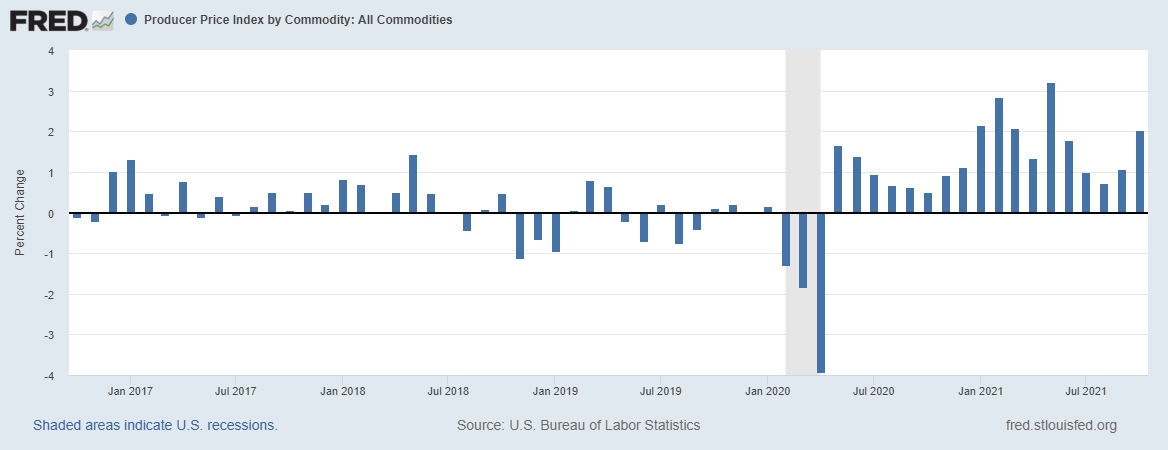

Of particular concern going forward is housing, as these prices account for a large portion of the overall CPI print and are—as was expected—finally catching up to the on-the-ground rent and home price realities we’ve been seeing in many U.S. housing markets. Another concern is that higher labor costs and historically frothy producer prices (driven in part by higher import prices) will get passed on to consumers in the coming months:

Today, the expectation—even among many inflation doves—is that this “transitory” inflation will be with us until at least early next year and could actually accelerate in the next few months: “It won’t be until the first quarter, when demand for consumer goods is much lower, that supply constraints might ease. If inflation looked hot in October, just imagine what November and December might bring.” Other experts, however, see potential supply-side constraints lasting through the end of2022.

Given these concerns, the tone in Washington has abruptly changed, as Reuters notes: “For both the Fed and the Biden administration, what was an adamant faith in transitory inflation has been tempered”—to say the least.

So What Happened?

I dare not get too far into the weeds as to why the confident “transitory” predictions seem to have fallen so flat, but a few things are worth noting:

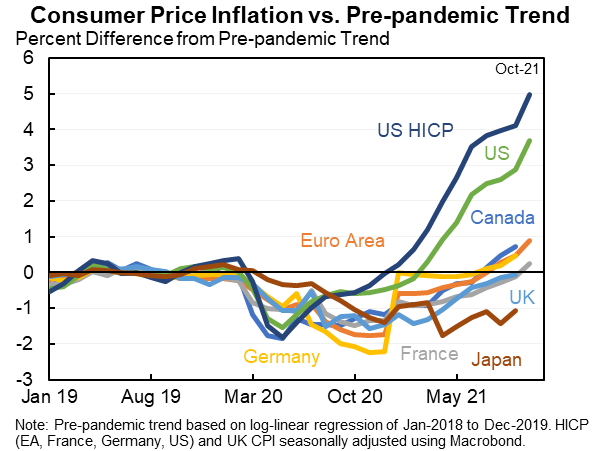

First, per Harvard’s Jason Furman (repeatedly, in this Twitter thread), the U.S. experience right now really is, contra Paul Krugman and others, unique:

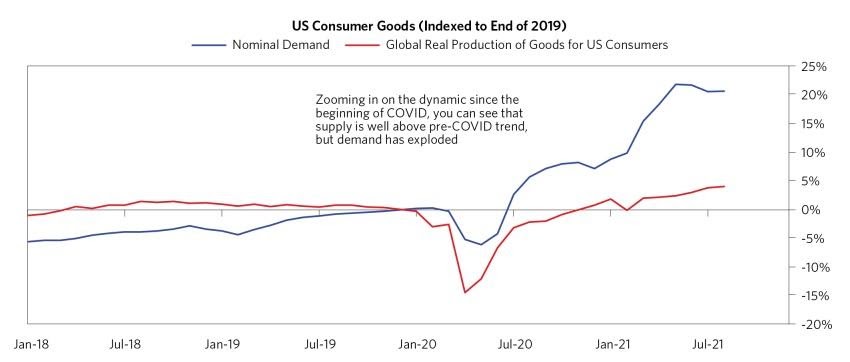

Furman also notes in that series of charts/tweets and in a separate series teaching some broader macroeconomic points that the common argument from Team Transitory that all of this is just supply-side stuff—pandemic-related shortages of workers/output or supply chain problems at ports and elsewhere—just doesn’t hold water. For example, all of the countries above are dealing with similar pandemic and supply-side issues, yet the U.S. experience still stands out (a lot). (Feel free to click through the links to learn more—the last one is particularly useful.)

Furman—who was most definitely not an inflation hawk earlier this year and generally supports Biden’s agenda—therefore argues in a new Wall Street Journal op-ed that, while there are some supply-side constraints, most of the blame for the current inflationary situation in the United State should fall to the demand-side, i.e., the U.S. fiscal and monetary response to the pandemic:

Inflation in the U.S. was similar to what the euro area experienced going into the pandemic, but prices have risen a cumulative 4% more in the U.S. over the past two years. The oversize and poorly designed $2.7 trillion fiscal stimulus passed in December and March is at least partly to blame for the divergence. The Federal Reserve has continued de facto to loosen, with the Goldman Sachs Financial Conditions Index showing that the combination of lower long-term rates, higher stock prices and other financial changes has been the equivalent of more than a percentage point cut in the federal-funds rate since November 2020.

In other words, we spent a ton of deficit-financed money, and the “real” (inflation-adjusted) federal funds rate (the rate the Fed sets for overnight bank lending) actually fell—right in the middle of an already-strengthening economic recovery. Ther result: “uncomfortably high” inflation that’s likely to persist into next year.

Others share Furman’s diagnosis and conclusions. For example, AEI’s Jim Pethokoukis recently pointed out this handy chart and quote from hedge fund Bridgewater: “Today, demand is surging, and supply is also growing, but it just can’t keep up with demand. There are not enough raw materials, energy, productive capacity, inventories, housing, or workers.”

Such analyses seem to vindicate the relatively few Beltway voices in early 2021 who were urging caution on—if not outright opposition to—the American Recovery Plan. As you’ll recall from my cautionary contribution in February, there were plenty of signs at that time that (1) with vaccines proliferating and restrictions easing, the U.S. economy was on its way to recovering; (2) that the pandemic recession bore little resemblance to the deeper, more systemic Great Recession (and thus called for a different policy response); and (3) the ARP’s fiscal stimulus far exceeded the “output gap” between current and pre-pandemic-trend production and, when combined with previous trillions in pandemic spending and super-easy Fed policy, could produce inflationary pressures. As I noted then, “[e]ven some left-leaning economists,” such as Treasury Secretary Larry Summers and former IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard, “warn that even more front-loaded stimulus, plus the aforementioned economic conditions (consumer spending, etc.), could spark a serious bout of inflation, thus triggering a harsh response from the Federal Reserve (higher interest rates, monetary ‘tightening’), and possibly causing another painful recession.”

In the last week, both Blanchard and Summers have taken their victory laps. And others are joining in.

Why It Matters

Maybe they’re all wrong and inflation will subside relatively soon, thus vindicating Team Transitory” (at least using a very liberal interpretation of that adjective), but plenty of risks remain.

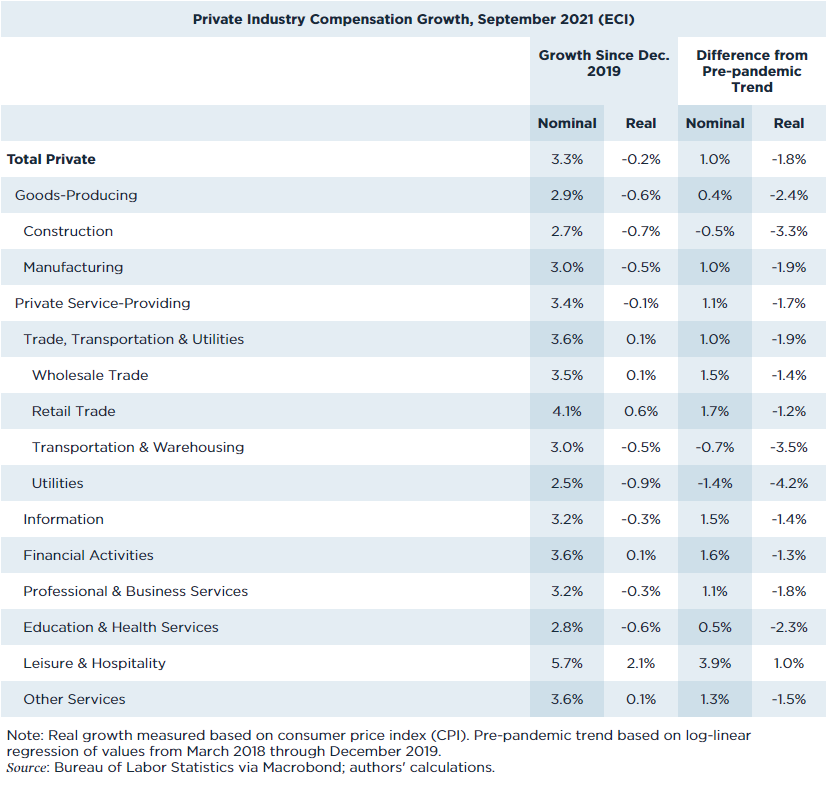

For starters, widespread price increases are having a negative effect on many Americans’ overall living standards. Most obviously, high inflation can be just brutal for Americans, especially poorer ones, who are no longer working and instead are living off of fixed incomes that don’t rise along with prices. Because inflation is outpacing (impressive) wage growth, moreover, it “has taken away all the wage gains for workers and then some”:

Thus, after adjusting for inflation, workers in almost every private industry—the big exception being leisure and hospitality—have seen flat or falling real compensation, especially when compared to the pre-pandemic trends:

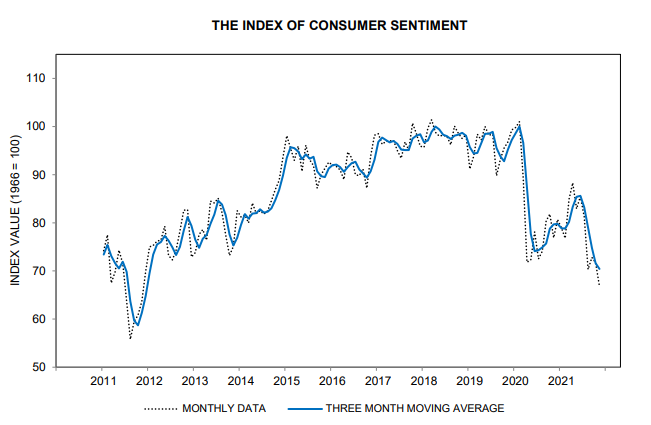

Persistent, visible price increases also fuel American economic anxiety, as they serve as an immediate and constant reminder that one’s paycheck today might not be sufficient to cover expenses tomorrow. Such worries can be especially acute following a long period of sustained, low inflation in the United States (which we just had). It’s thus no surprise that recent polling uniformly shows most Americans to be very concerned about inflation, and that consumer sentiment has plummeted:

Inflation fears also can affect U.S. economic policy. According to Bloomberg, for example, West Virginia residents, who tend to be older or on fixed incomes and are worried about more Washington spending fueling further price hikes, are a big obstacle to critical Sen. Joe Manchin’s support for Biden’s $1.75 trillion Build Back Better plan. Voters in other key spots are similarly concerned. Given such threats and Biden’s collapsing poll numbers, the White House has abruptly shifted gears to show that the president is working hard to alleviate inflation and how his agenda will (of course!) actually make things better. Meanwhile, Republicans are using inflation (sometimes in annoying, ham-fisted ways!) to undermine the BBB and convince voters to ditch Democrats in 2022.

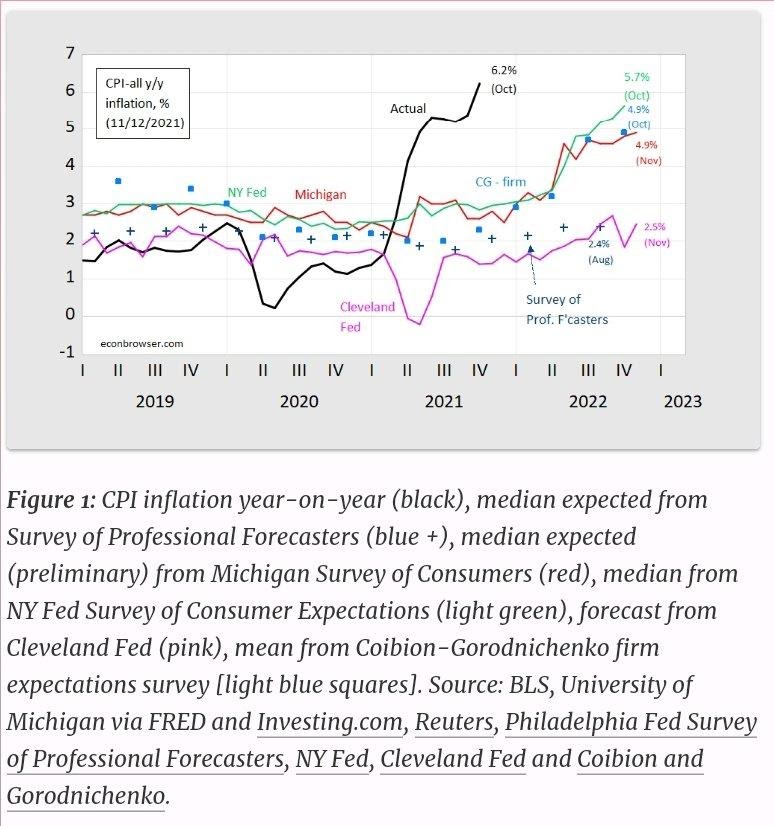

Changing public sentiment about inflation also can affect monetary policy. For example, Powell has repeatedly said that his policy stance stems in part from signs that most Americans didn’t expect prices to rise much in the long run. Thus, there was little risk of a “wage-price spiral” (i.e., workers demand higher pay to offset expected price hikes; employers hike prices to offset higher costs; rinse, repeat) that has historically played a role in past U.S. inflationary periods. “For inflation to move up in a persistent way that moves inflation expectations up,” Powell said in April, “that would take some time, and you would think it would be quite likely we would be in very strong labor markets for that to be happening.”

Fast forward to today, and those expectations are indeed rising (after months of under-shooting):

Furman added last week that expectations for inflation over the next five years are “the highest they’ve ever been,” and then they hit another record yesterday (though this is a relatively new metric). Politico reports that businesses are getting concerned too, citing it as their “biggest external risk factor” in the months ahead.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that the 1970s are just around the corner, but a few more months of these kinds of pressures (which are, again, expected at this point) could put the Fed in a very tough spot: Either keep rates ultra-low and risk overheating the economy, freaking out investors, and cementing inflation to try to recover the millions of American workers still absent from the labor market or accelerate monetary tightening to check inflation and risk leaving workers sidelined or even bringing on a recession. Former Fed official Bill Dudley thinks they’re already there, left to “hope and pray that inflation subsides and the labor market loosens up” or “tighten monetary policy sooner” and reap the whirlwind. (Yes, these are the very risks that Summers and others warned of back in February when the ARP was being considered.)

Even economists who generally support the Fed’s approach are concerned:

The Fed has insisted on characterizing the current inflation run as “transitory,” even with the consistent increases.

“The risk that they cannot hold the ‘transitory’ line is rising,” Shepherdson wrote. “We remain baffled as to why Chair Powell chose not to warn markets explicitly of the risk of a run of big increases in the core CPI over the next few months; the components which drove up the October reading were all foreseeable.”

The question ahead is how long the current space of inflation will last, and Shepherdson said he expects core inflation, now around 4.6% year over year, to top out over 6% and run that high through March, “massively increasing the pressure on Chair Powell and other Fed doves.”

LaVorgna said he also expects some relief next year, but not without inflation running around 6% for several more months.

Or as Mohamed El-Erian, chief economic adviser at Allianz, just told CNBC, “I think the Fed is losing credibility. … I’ve argued that it is really important to reestablish a credible voice on inflation and this has massive institutional, political, and social implications.”

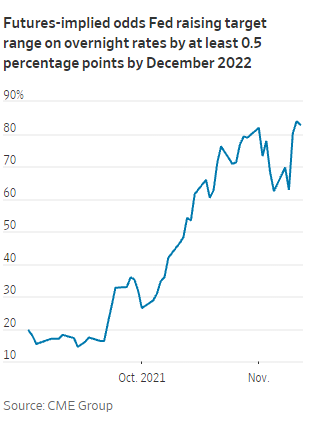

Now, “credibility” is a pretty subjective thing, but there are already signs that the market thinks the Fed will have to raise rates more than it currently expects: as noted in the Wall Street Journal, for example, the latest Fed projections were for—at most—a quarter-point interest rate increase by the end of next year. Market actors, by contrast, now overwhelmingly expect at least a half-point by the end of next year—a dramatic increase in only a few weeks—and “futures now put the odds of the Fed raising rates by three-quarters of a point or more at 54%.”

Even if the Fed doesn’t follow suit, moreover, persistent inflationary pressures—and market doubts about the Fed’s forecasting abilities—could push private actors to take matters into their own hands, raising market interest rates to ensure sufficient returns and thus cooling the U.S. economy in the process.

Summing It All Up

All of this might sound like I’m uber-pessimistic about the U.S. economy and inflation, but I’m really not. If forced to choose, I’d guess that things settle down in the next six months or so as stimulus fades, supply chain constraints ease, and some workers rejoin the labor force (and/or employers adapt). But the last several months should, I hope, provide us with some teachable lessons about the current economic moment (beyond the obvious “pandemics are messy” point):

First, messaging matters. Overconfident predictions of demand-side booms and easy economic hurdles during obviously chaotic and uncertain times—not to mention silly claims that Americans worried about tighter budgets are selfish or should welcome lower living standards—are not just politically tone-deaf. When coming from key economic policymakers, they can also affect market expectations and ultimately threaten the economic recovery (not to mention those policymakers’ jobs). A little more humility could’ve gone a long way.

Second, it seems quite clear at this point that the ARP was poorly designed in terms of timing, scope, and (bear with me) economic philosophy. As noted by Pethokoukis, economist John Cochrane, and others, there has been an almost-religious belief among many on the left that pumping trillions of dollars into the U.S. economy and continuing ultra-easy monetary policy would seamlessly boost production and living standards. Reality, however, has now shown quite clearly that you can’t just jack up demand and expect supply to quickly match—especially when governments restrict that supply with all sorts of bad policies (as we’ve repeatedly discussed). As Furman put it, “It turns out, in the short run, you try to push too hard, too fast, and the economy can’t make the adjustment on the real production side, and you end up with more inflation and that’s what we are seeing.”

I don’t expect folks on the left to suddenly become humble libertarian supply-siders after this moment passes, but there does appear to be some begrudging acknowledgment from many center-left folks that mistakes were made this year, and that at least some of the economy’s regulatory barnacles need removing.

Hopefully, that won’t be transitory.

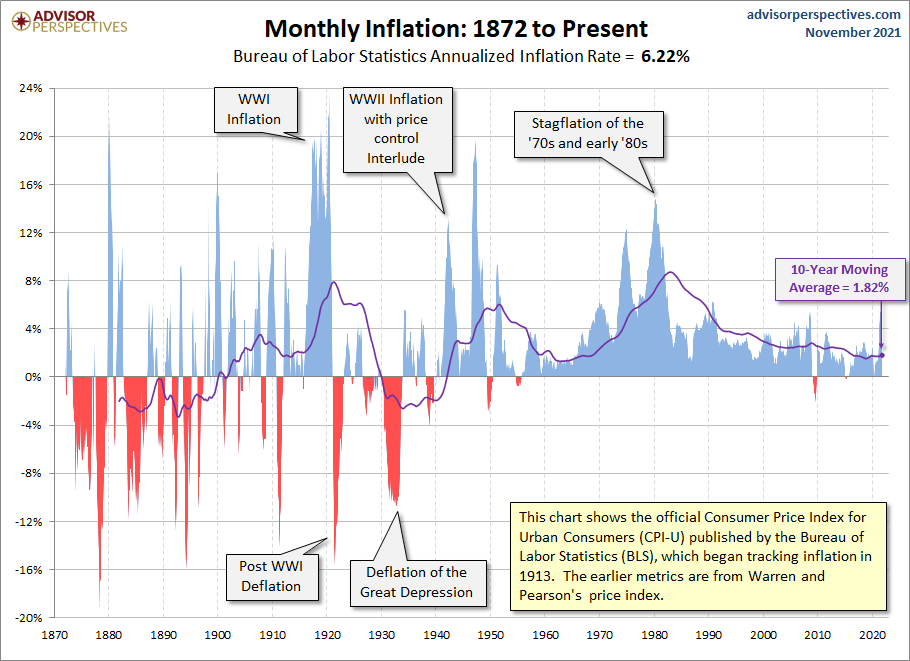

Chart of the Week

Sure, why not have one more inflation chart:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.