Dear Capitoliat,

With President Trump’s legal options dwindling and the reality of a Biden presidency dawning on the Republican party, the biannual tradition of declaring that a U.S. election, like, totally confirms one’s policy priors has begun. Supporters of the president’s populist policies—if not the man himself—have taken to various media outlets to declare confidently that the GOP is now a “workers’ party” and that “Trumpism” is most definitely the party’s future, with or without Trump.

The precise meaning of “Trumpism” differs among the various correspondents, but they seem to agree on two things. First, Trumpism is not just about “supporting Trump” but instead reflects specific policy priorities among the new GOP “working class” base. Second, the core of these policy priorities is economic nationalism—in particular skepticism of, if not outright hostility to, trade and immigration—which will help certain American voters and regions, particularly the industrial Midwest (“Rust Belt”), and thus win their votes The Successful GOP of Their Future will favor more government restrictions on these two things in direct contrast to “traditional” Republican support of freer markets. Here’s how Sen. Marco Rubio put it in a recent Axios interview:

We still have a very strong base in the party of donors and think tanks and intelligentsia from the right who are market fundamentalists, who accuse anyone who’s not a market fundamentalist of being a socialist to some degree. … If the takeaway from all of them is now is the time to go back to sort of the traditional party of unfettered free trade, I think we’re gonna lose the [Trump] base as quickly as we got it. … We can’t just go back to being that.”

It’s a neat and tidy story, for sure, but it doesn’t seem to me to be tethered to reality (though I of course work for a think tank that proudly supports free markets). Indeed, among the various “Trumpism” op-eds I’ve read so far is barely a shred of hard evidence supporting the GOP’s obvious and necessary embrace of economic nationalism in order to win without Trump in 2024 and beyond. In fact, most of the evidence I’ve seen thus far actually undermines the two core points above.

So I’ll review that evidence today, and let you, dear reader, draw your own conclusions.

The Polls

First, there’s little in the public polling to indicate that Republican voters have suddenly and strongly embraced economic nationalism. For example, longtime surveys from Pew, Gallup, and the Chicago Council—helpfully collected and published by my Cato colleague Simon Lester in August—show that self-identified Republican support for free trade agreements and international trade actually hit all-time highs in the last year:

The above polling data tell one of two stories, neither of which supports the Trumpism thesis: Either Republican voters have become stalwart supporters of trade (hooray!), or large chunks of the Republican electorate (and Democrats too) simply base their support or opposition to trade and trade agreements on who’s been in the White House (and thus steering U.S. trade policy). As I wrote in a 2018 paper, the latter scenario is much more likely: Because most Americans neither care about nor are directly impacted by trade, their views on the issue simply parrot those of their political leaders or fluctuate with the economy (better economy = more supportive of trade liberalization). Trump, as usual, amplified these pre-existing trends, especially with respect to tariffs and NAFTA: If he was for/against it, so were a majority of Republican voters (while Dems said the opposite).

Whether my thesis is correct, however, is immaterial for our purposes: There is just no sign in the public polling of a massive, bottom-up demand for more protectionism among Republican voters.

(Spoiler: I’m probably correct.)

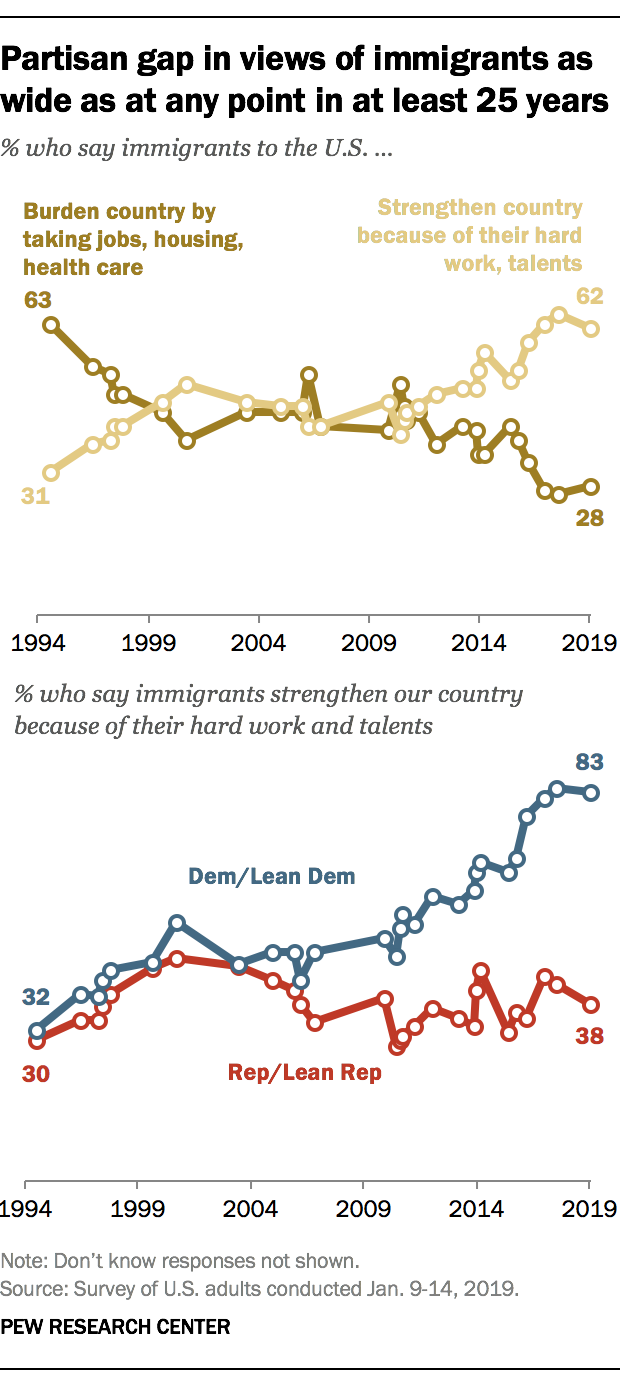

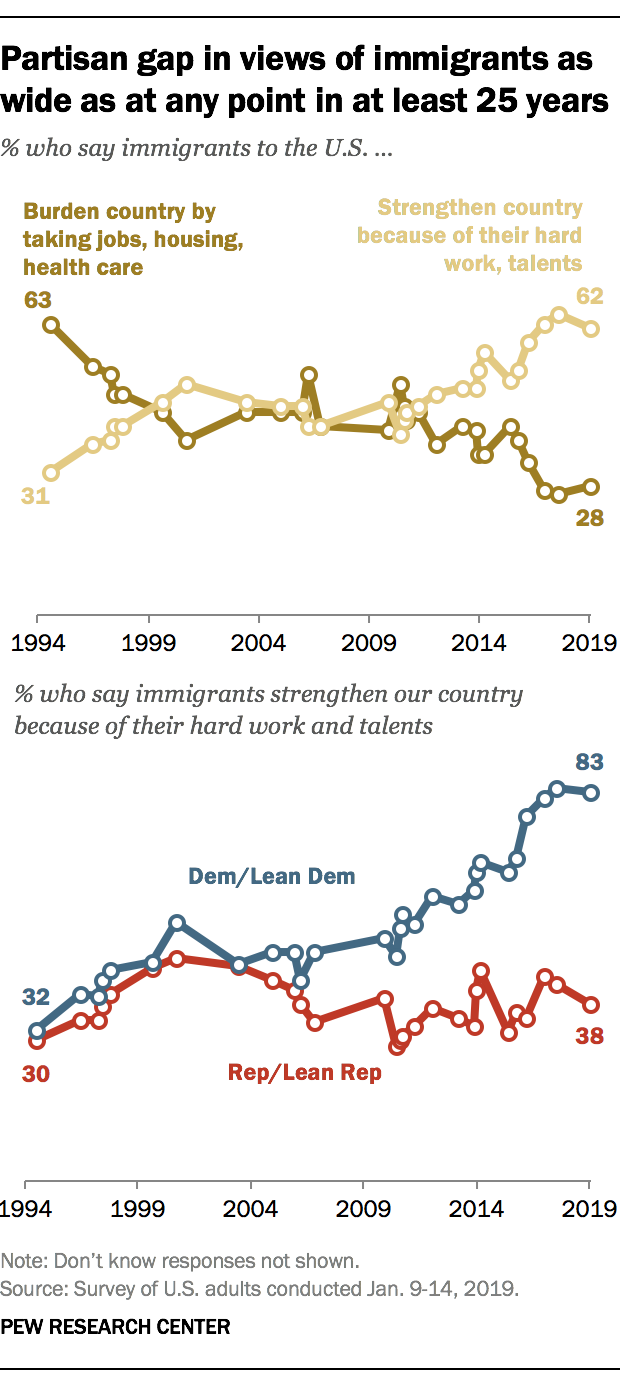

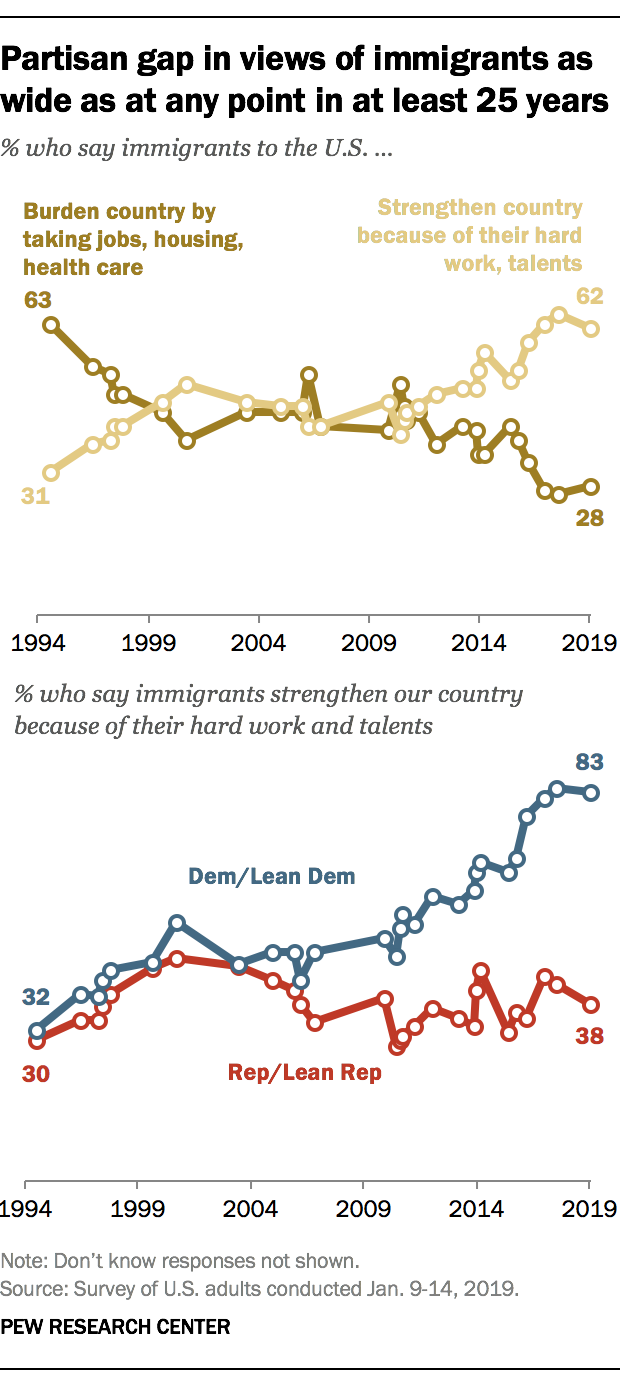

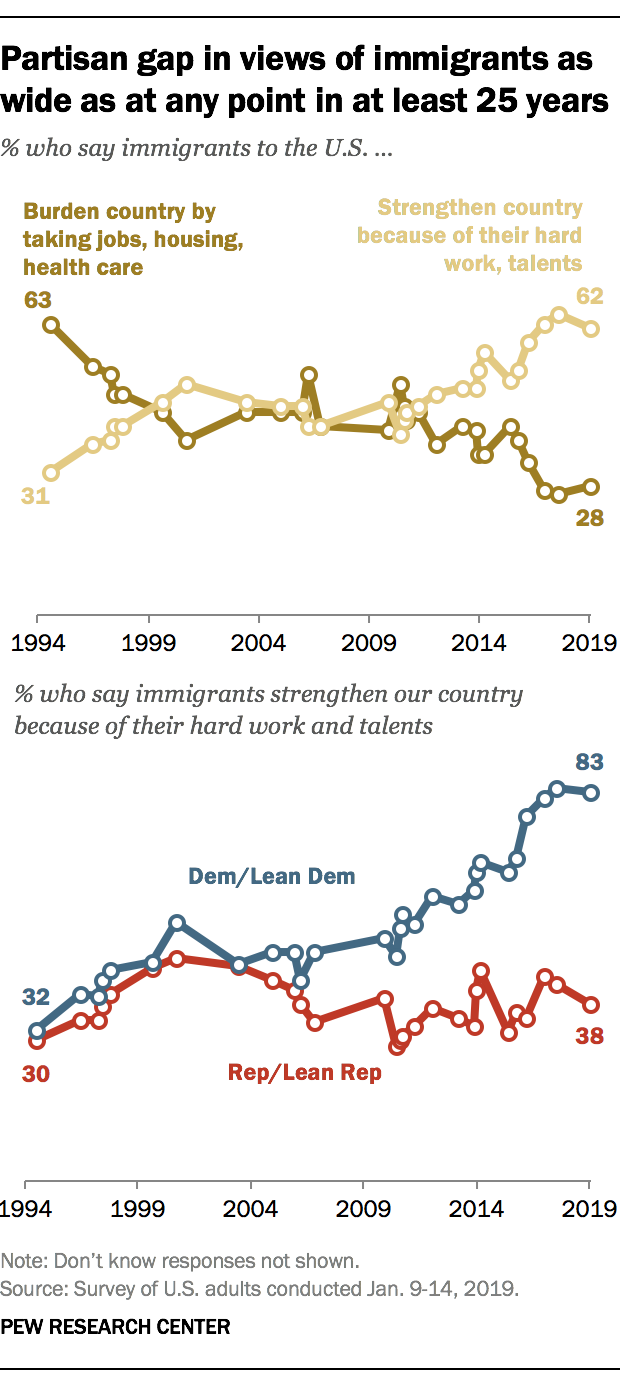

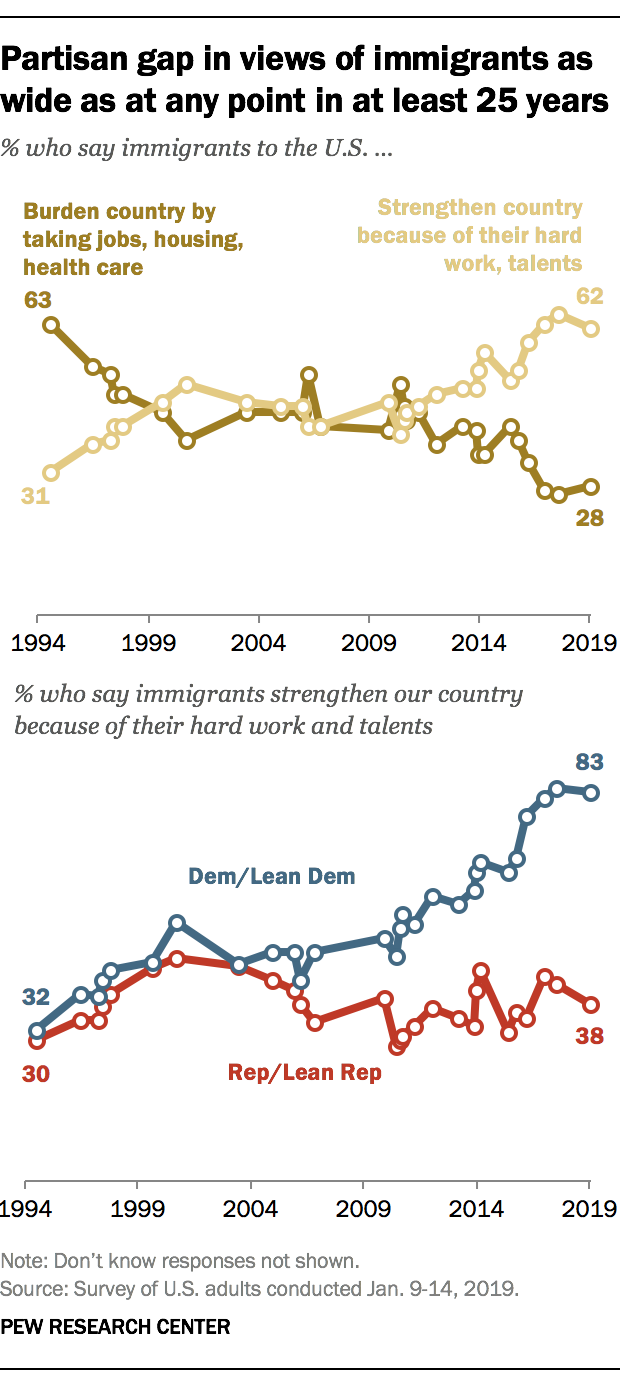

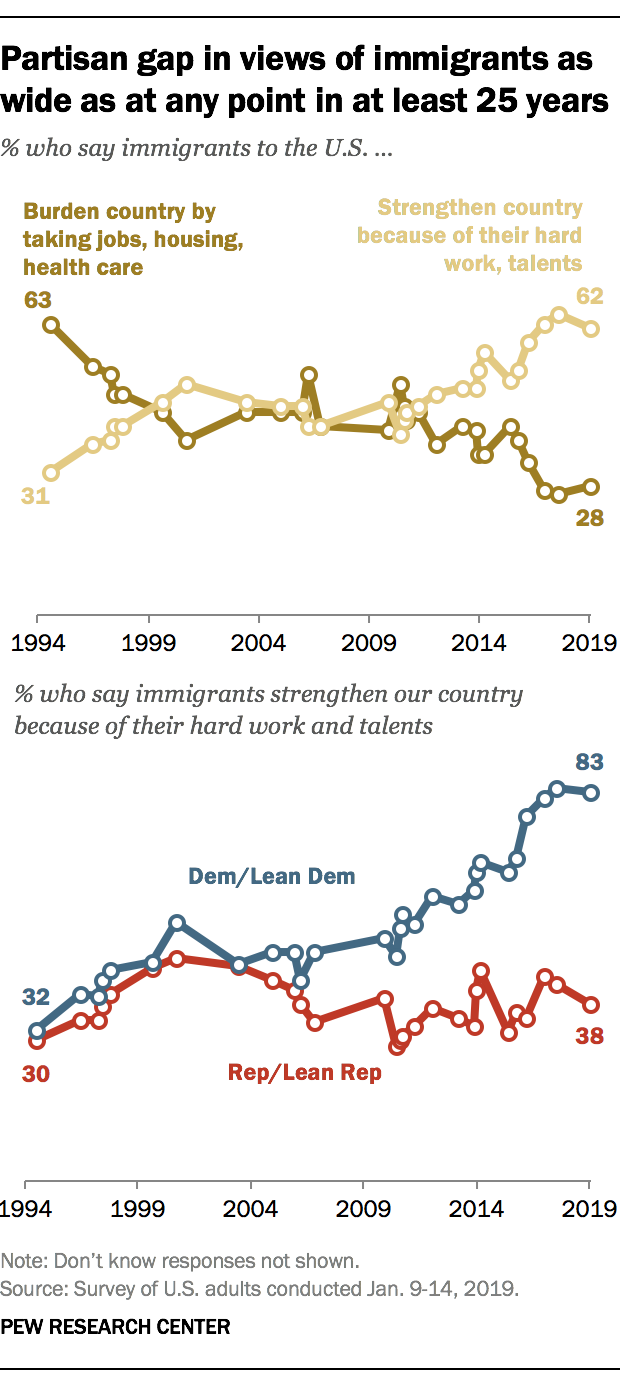

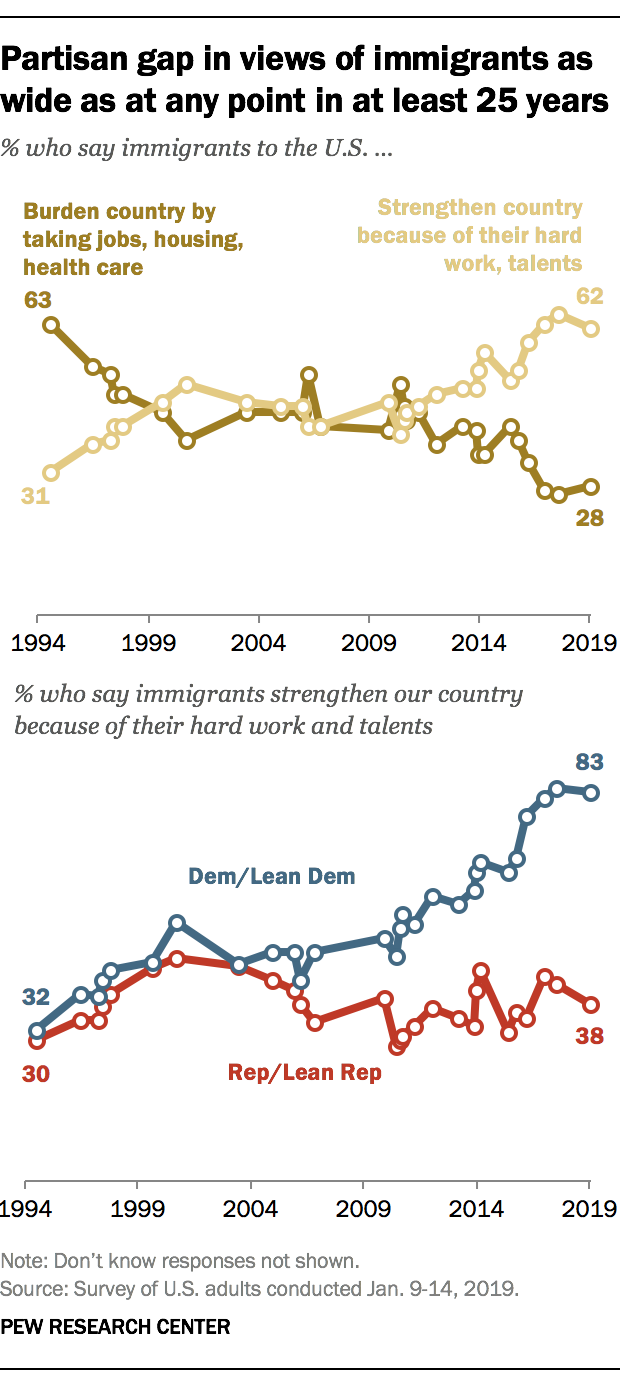

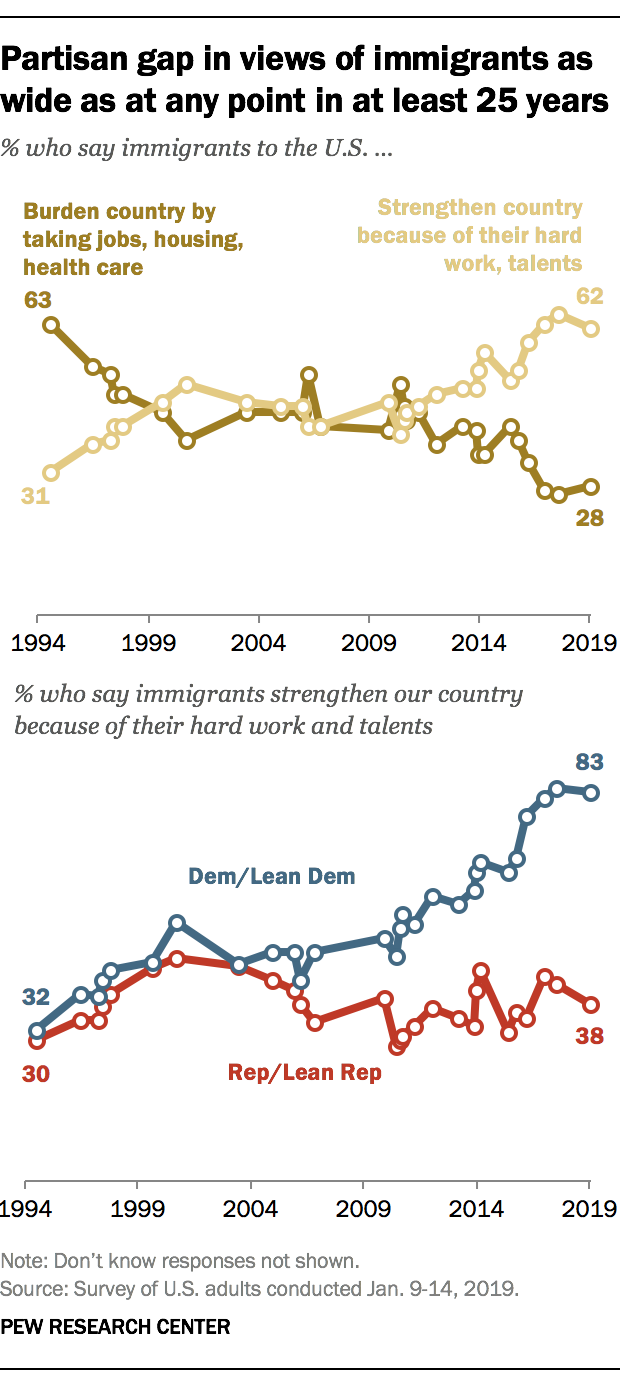

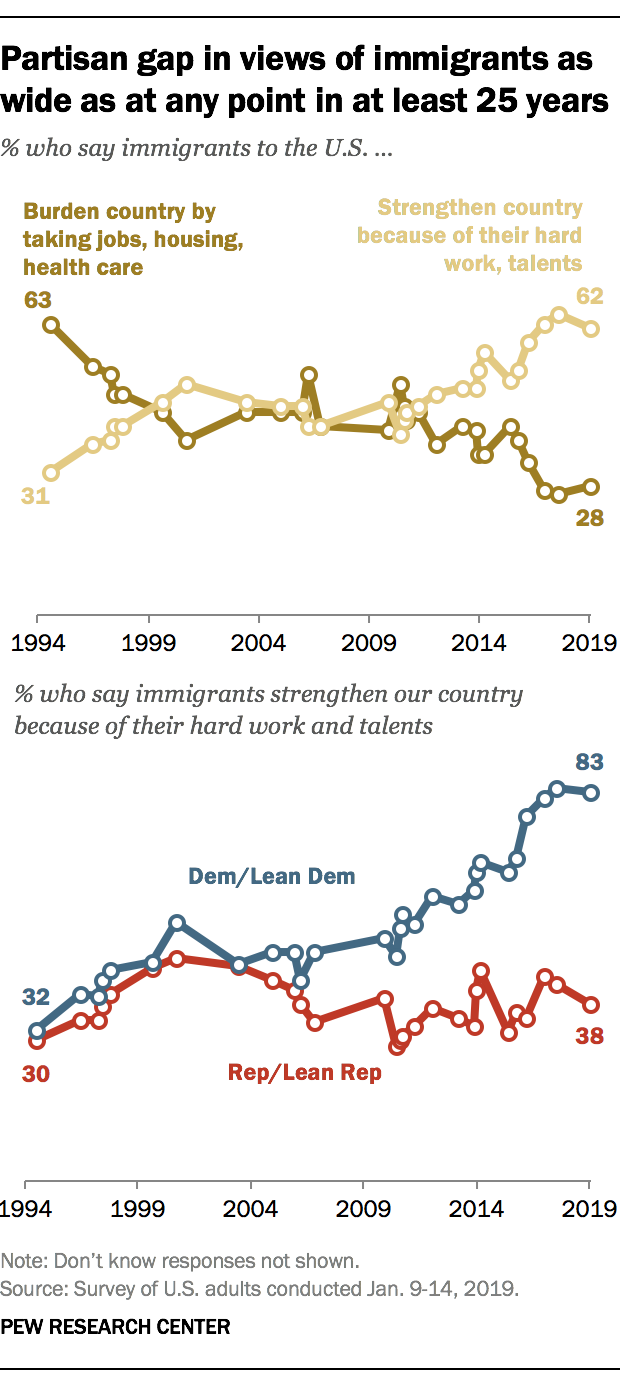

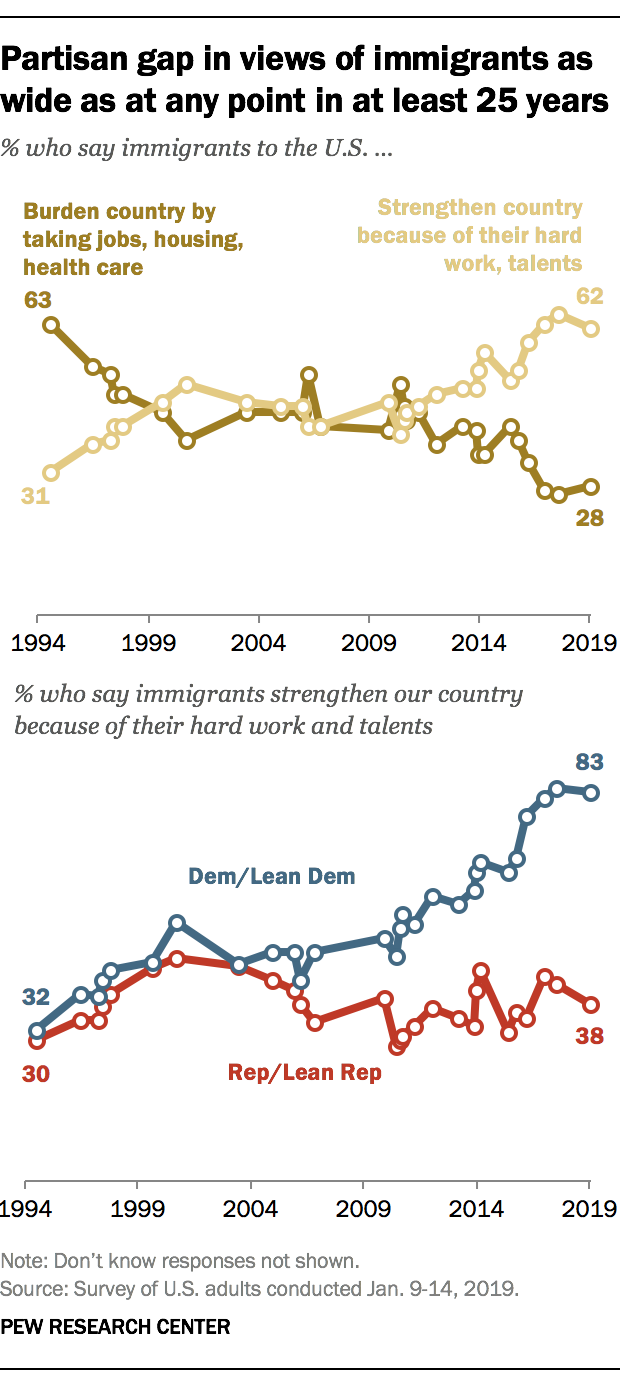

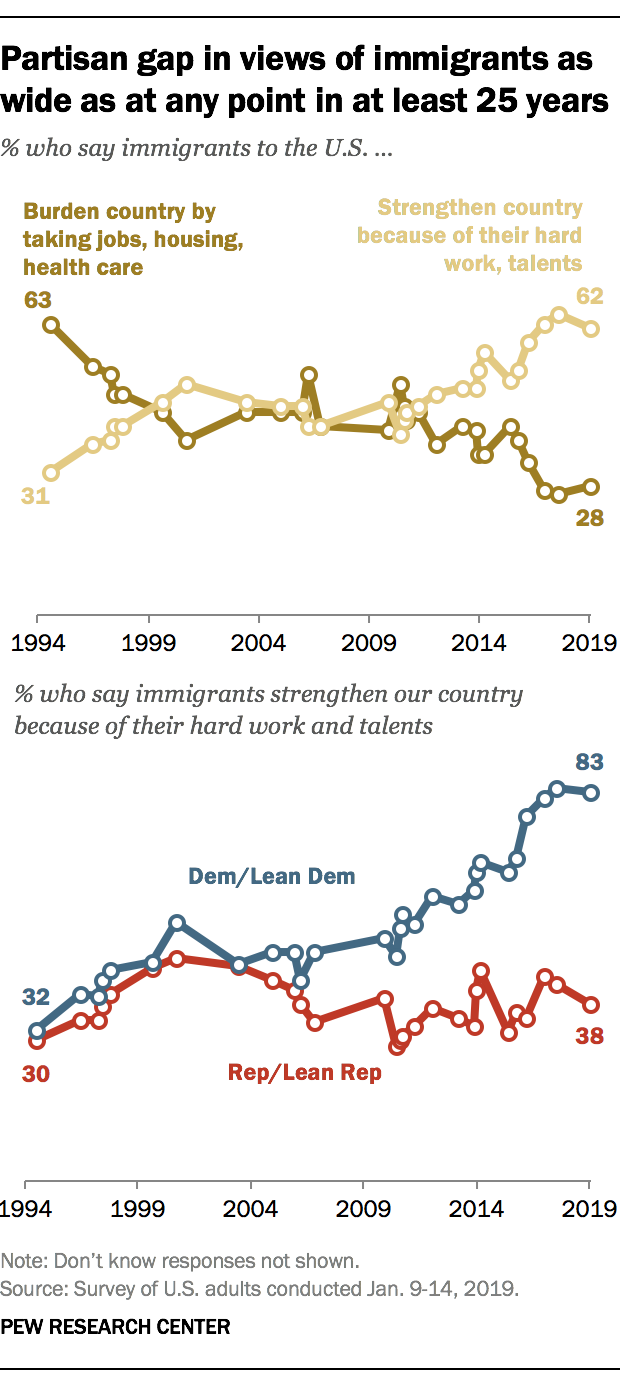

Immigration polls tell a similar (albeit slightly different) story: Republicans still aren’t huge fans of immigration, but there has been no surge in GOP nativism since Trump burst on the scene in 2015. For example, a 2019 Pew poll found that only 38 percent of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents said that immigrants “strengthen the country” (similar to other polls), but this figure was relatively flat since the mid-2000s (when George W. Bush was winning 40 percent to 44 percent of the Hispanic vote) and actually up a little since the mid-’90s:

Gallup found a similar trend in 2020, with GOP support for increasing immigration levels generally flat over the last two decades:

Republicans in that poll were evenly split on whether overall immigration levels should be decreased (48 percent) or increased/maintained (49 percent: 13 percent the former and 36 percent the latter). Gallup earlier found, moreover, that Republicans and GOP-leaners overwhelmingly supported granting a pathway to citizenship for immigrant “Dreamers” and modestly opposed ending family-based immigration policies. By contrast, GOP voters took a much harder line on two Trump priorities: the Wall and sanctuary cities.

Similarly, a 2020 Morning Consult poll found that only 19 percent of Republicans/leaners wanted Dreamers deported, and other polls have found the same thing.

All of these polls permit the same general conclusion: Republicans’ views on immigration remain more restrictionist than those of Democrats and independents, and these loyal voters definitely support the Trump administration, but—just like trade—there’s no sign of a new, bottom-up mandate for heightened GOP nativism. It’s just more of the same.

The Election

Next, the election results provide little support for the idea that the GOP can win national elections by just tripling down on the Trump coalition (even as it became a little more diverse). First, as Jonah noted last week, Trump’s own campaign didn’t focus on an anti-globalist message in the waning days of the election. As the WSJ’s Greg Ip subsequently put it:

Donald Trump’s election in 2016 was widely seen as a rebuke of globalization, immigration and free trade. This year, those issues barely registered. They were largely absent from Mr. Trump’s campaign speeches and ads, and didn’t rate among voters’ most important issues, according to exit polls.

(For more on Team Trump running away from immigration restrictionism in the waning days of the campaign, read here.) Meanwhile, Democrats and NeverTrump Republicans repeatedly hit Trump on his trade wars, further indicating political liability, not strength.

Second, there’s the small problem that Trump actually lost and it wasn’t particularly close, especially given that he was the incumbent. And it’s how Trump lost that should give Team Trumpism further pause. For starters, preliminary exit polls show that Trump got just crushed by independents, whom he actually won in 2016 and whose support for trade and immigration—as the polling above shows—has significantly increased in recent years. (Obligatory caveat: Preliminary results from exit polls are notoriously sketchy.)

He also lost major ground among middle class voters, while his only substantial gains came among voters making more than $100,000:

Maybe more detailed exit poll data will change these results, but as of now, there’s little (if any) ground to conclude that Trumpism was a recipe for winning the “middle class” or squishy independents—even in the “Rust Belt.”

More importantly (and more concretely), county-specific analyses of the 2020 vote call into question the theory that Trumpy economic nationalism can drive future GOP electoral victories. In fact, Trump’s loss may have hinged on shedding voters in parts of the country that (1) wouldn’t generally benefit from, be targeted by, or strongly support protectionism and nativism; and (2) are expected to experience a disproportionate share of population growth over the next decade. (As I’ll explain in the next section, it’s far better to help American workers via broad-based tax, regulatory and monetary policies that generally lift all boats—and were shown to work in the Trump administration too!—instead of trying to prop up a select few. But since the Trumpism-without-Trump thesis is largely about securing future political victories, these are relevant considerations.)

In particular, several recent analyses show Trump’s biggest losses compared to 2016 came in “traditionally Republican” counties that have more diverse, more “globalized” economies, as well as voters who are hardly what you’d call Trumpy nationalists. (I happen to live in one of these places.) In many states, Trump’s underperformance in these localities looks to be what cost him the state at issue.

According to economist Jed Kolko, for example, Biden made significant gains against Trump in counties that (1) had a stronger economy (faster job growth, more population growth) during the last four years and suffered less from the pandemic this year; and (2) have a brighter economic future (due to higher levels of education, a diverse range of industries, and fewer “routine jobs” at risk of automation) and are thus projected to grow faster in the coming years. These are generally not the places where a protectionist message sells:

Kolko’s analysis also shows that Biden-gain counties include a lot of “Republican” places like the suburbs and red states. He finds, in fact, that “both denser and more sprawling suburbs of large metros swung toward Biden by about 5 points, while more traditionally Democratic urban counties didn’t shift much either way.” Thus, Trump’s unpopularity in these “traditional Republican” places—places, again, that probably aren’t embracing economic nationalism anytime soon—may have been determinative.

A separate New York Times Upshot analysis finds the same thing about the suburbs and provides this sweet chart to hit the point home:

Anything above that dotted diagonal line is a Trump vote-loss between 2016 and 2020. And again we see how these losses aren’t just in blue states or even blue counties that Republicans can just ignore—all of the orange dots are in “battlegrounds” and all of the ones on the left side of the chart voted R in 2016.

(There are a lot of orange dots!)

Brookings, meanwhile, found that Biden just dominated in economically successful localities—representing about 70 percent of national GDP (up from 64 percent Clinton in 2016)—and, more importantly (I think), “flipped half of the 10 most economically significant counties Trump won in 2016, including Phoenix’s Maricopa County; Dallas-Fort Worth’s Tarrant County; Jacksonville, Fla.’s Duval County; Morris County in New Jersey; and Tampa-St. Petersburg, Fla.’s Pinellas County.” Other than New Jersey, those flips are again in politically important places. By contrast, four of the five most economically significant counties that Trump won were in politically meaningless New York, Oklahoma, or California (with Dallas-Fort Worth suburb Collin County rounding out the top five):

On-the-ground reporting mirrors these national analyses in key places like Pennsylvania, Michigan, Arizona, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and my birth-state Texas (including the aforementioned Tarrant County). Over and over again, we see Trump losing ground in relatively diverse, dynamic, and growing areas that don’t want or need protectionist policies—and in fact would probably be hurt by them—and which used to vote Republican. The end result: “Joe Biden made strong gains in the suburbs, including traditionally Republican exurbs. Mr. Trump’s more modest gains in small towns and rural counties weren’t enough to stop swing states—Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and apparently Georgia—from moving into the Democratic column.”

Now, I am not naïve enough to think that Trump’s positions on trade and immigration are what caused Republican-leaning suburbanites to ditch him for Biden, but that’s definitely not the point. The point is that these places (1) won’t generally benefit from economic nationalism; (2) tend to be quite supportive of both “globalization” and immigrants (by significant margins); (3) may have cost Trump the 2020 election; and (4) will likely become more electorally significant in the future because of their disproportionate economic and population growth. Can Trumponomics—with its heavy focus on manufacturing, economic pessimism, and nationalism—win these places back, or can the GOP pin its hopes on just stoking turnout in other places that might be more attracted to such policies? Color me skeptical.

Georgia is probably the poster child for this skepticism, but it’s certainly not alone. For example, Allegheny County—home to the “Steel City” (Pittsburgh) that has long since diversified away from steelmaking—probably sealed President Steel Tariff’s fate in Pennsylvania last week. (Irony abounds!)

And even though Trump won my home state of North Carolina, it provides another good case study. According to the latest population growth projections, almost all of the state’s impressive growth over the next decade will occur in or around four metro areas: Charlotte, the “Triangle” (Raleigh, Durham, Chapel Hill), the “Triad” (Greensboro, Winston-Salem, High Point) and Wilmington. Unsurprisingly, Biden handily won the densest urban/suburban parts of these areas (Wake, Mecklenburg, and Guilford counties), but he also gained in all of the surrounding areas too. In fact, Trump/Republicans lost ground (and Biden gained) in every single one of North Carolina’s top 20 “future growth counties.”

I certainly don’t believe that “demographics are destiny” here or anywhere else, but it sure doesn’t seem like Trumpism is the key to reversing this trend in the future.

But what about the congressional gains in these very same areas? Well, those appear to have come from the “traditional” GOP playbook (stressing lower taxes and less regulation) and Democrats’ own anti-capitalist, anti-police messaging and policy problems—not a heavy reliance on Trumponomics. (The House GOP’s 2020 playbook even links to a very non-Trumpy trade speech from Ways and Means Committee leader Kevin Brady.)

Maybe the best example of this dichotomy came in the Omaha suburbs (Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District), where pro-NAFTA, anti-tariff, pro-Dreamer Republican Don Bacon cruised to victory while Trump got smoked by 6.5 percent (after winning it by 2 percent in 2016). Does this mean the GOP must now embrace “Baconism” to guarantee future political victory? Of course not. But it’s a clear reminder that 2020 was about Trump, not “Trumpism,” and that pro-trade/pro-immigration policy isn’t necessarily the political kryptonite it’s now made out to be—even in the Heartland.

Will Nationalist Policies Actually Help the Working Class?

Finally, there’s the not-insignificant issue of whether the economic nationalist aspects of Trump’s agenda have actually been good for “forgotten” communities or people in the United States. And here, again, the thesis underwhelms. As I wrote on these pages just a few weeks ago, Trump’s tariffs and trade wars hurt the economy overall but particularly hurt the U.S. manufacturing sector in terms of both jobs and output. Indeed, a slew of pre-election articles showed that Trump’s “America First” policies—pro-manufacturing and anti-imports/outsourcing—not only failed to reverse the seismic forces that for decades affected corporate and consumer decision‐making (and thus certain U.S. manufacturing companies and jobs) but probably made things worse for the very places and people those policies were supposedly intended to help.

New research from the St. Louis Federal Reserve really hits this second point home, finding that certain states’ output and employment suffered between 2018 and 2019, as trade-exposed firms curtailed operations in response to Trump’s tariffs and foreign retaliation. Two of those states were Michigan and Arizona, which President Trump won in 2016 but lost this year.

Data from the BEA reiterate these findings: Key Midwest states all experienced slower manufacturing growth in 2018-2019—when the trade wars were in full swing—than in the years before they began. And Trump went 1-for-4 here:

Surely, residents of these and other states voted for a wide variety of reasons (many of which have nothing do with economics), but these results undermine the idea that protectionism is a surefire political winner, even in the “Rust Belt.”

Trump’s trade wars also hurt farmers, thus necessitating tens of billions of dollars in federal government bailouts to cover lost sales and lower crop prices. And new research shows that this pain actually did have political ramifications, with Republicans losing votes in soybean-producing localities between 2016 and 2018. I did a similar, less-rigorous analysis back in 2018. Using that template and adding in 2020, it looks like Republicans clawed back some of their 2018 losses with Trump at the top of the ticket, but were still down substantially versus 2016 in most of those districts:

There’s less research (so far) on the economic harms imposed by Trump’s death-by-a-thousand-cuts approach to reducing legal immigration, but for immigration in general the literature shows substantial, widespread benefits against only limited harms for American workers. Past restrictions, moreover, have actually encouraged outsourcing. (Immigration will be the focus of a forthcoming Capitolism newsletter.) Nevertheless, the few analyses we have (along with plenty of anecdotal evidence) show that Trump immigration policies have likely hurt the economy and will continue to do so in the future.

So what about the impressive job and wage gains that we saw in Trump’s first three years? As I wrote on these pages a few weeks ago, those likely resulted from sound monetary policy and free-market policies (tax reform, regulatory relief, etc.) goosing the already-decent trends in the Obama era—free market policies that are often derided by the populist right and that were probably undermined, not supported, by economic nationalism.

Summing It All Up

So “pro-worker” economic nationalism isn’t suddenly in high demand among most American (even Republican) voters; probably won’t help the GOP win back the growing, formerly Republican exurban/suburban areas where Trump lost serious ground (and maybe the election?) in 2020; and definitely won’t help the vast majority of American workers. But we’re supposed to believe that these policies are the key to the GOP’s future electoral success, and that they—not the candidate with 100 percent name ID and the supernatural ability to dominate our collective brainspace, motivate blue collar voters, and make his enemies go insane—drove the GOP’s poll-vexing gains in 2020? My evidence aside, maybe that’s really the case. Maybe some career politician without Trump’s unique abilities can mimic his successes with policies that ignore (if not repel) much of the country and don’t actually help the working class, but appeal to a small, vocal minority of that cohort and serve as some sort of emotional balm for the rest. Maybe they can squeeze that shrinking turnip just a little bit tighter.

But, like I said, color me skeptical.

Chart of the Week

Foreign companies sure “outsource” a lot of jobs to the USA (source).

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.