Now that the dust has settled on President Donald Trump’s and congressional Republicans’ signature 2025 policy win—the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (or “OBBBA,” which is admittedly fun to say phonetically)—it’s a perfect time for Capitolism to review some of the law’s best and worst aspects. This exercise will not only force me to actually review the law (ugh) but also address the too-frequent reader criticism that Capitolism never says anything nice about Trump’s economic policies (umm, you know, like we so frequently did with President Joe Biden, LOL).

A complete and digestible accounting of the law today is, alas, impossible—even for this longwinded newsletter. The thing is simply massive and was passed at breakneck speed, and the effects of several of its provisions won’t be clear for a while. Indeed, it’s been more than two weeks since Trump signed the OBBBA, and we just got the Congressional Budget Office’s final score of the law’s fiscal impact. (Ah, the joys of arbitrary legislative deadlines, razor-thin vote margins, procedural arcana, and backroom negotiations!)

Still, we know enough about the OBBBA—and what makes good economic policy—to offer initial comments on the law, and some of its provisions are, in fact, quite good. Much of the law, on the other hand, is decidedly not good—nor is what the OBBBA says about modern U.S. economic policymaking more broadly.

As a non-paying reader, you are receiving a truncated version of Capitolism. You can read Scott's full newsletter by becoming a member here.

Hurray, the OBBBA’s Best Stuff

Before we get to the list, let’s establish a few basic principles for today’s grading. First, and most obviously, the U.S. government’s fiscal situation is very bad, getting worse, and driven mainly by unsustainable entitlement programs that grow faster than the economy and inflation, regardless of available revenues. The result is ever-increasing deficits that are politically sensitive but simply must be addressed at some point in the future (and the sooner the better).

Second, and also obvious, using federal economic policies to blatantly buy votes—in Congress or at the ballot box—is not only distasteful but also generates bad economic outcomes and political incentives.

Third, and as we discussed last year regarding taxes, good economic policy tends to have a few essential features: simplicity (easy to comply and for governments to administer and enforce), transparency (clearly and plainly defining the rules, obligations, and timing), neutrality (neither encouraging nor discouraging personal or business decisions), and stability (establishing consistent and predictable terms). Tax systems that follow these rules tend to have low rates, a broad tax base, simple and permanent rules, and very few loopholes. And the same principles generally apply to other economic policies too: permanent, broad, and transparent is much, much better than the alternative.

Now, on to the list.

1. Permanent full expensing.

Easily the best part of the OBBBA is something that tax wonks (and yours truly) have been championing for years now: permanent “full expensing,” which will allow U.S. businesses to write off covered investments immediately and fully instead of spreading those deductions over many years (a practice that, as Cato Institute tax guru Adam Michel and I discussed on a recent Cato podcast, never made much economic sense). The OBBBA provisions aren’t perfect in this regard—the permanent fixes are limited to spending on domestic R&D and “short-lived assets” (equipment, machinery, etc.), while expensing for structures is temporary (and thus has muted growth implications)—but the result here is still pretty great.

As Michel explained in a 2023 briefing paper, research shows that expensing specifically boosts capital investments and jobs because it improves companies’ after-tax investment returns and demand for labor. Subsequent analyses of the expensing provisions in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) confirm these findings, as well as an increase to U.S. economic growth. And research also shows that the TCJA’s phaseout of certain expensing provisions acted as a drag on U.S. investment. Expensing also makes investing in the U.S. more attractive than in countries with depreciation systems.

It’s great tax policy that has the added benefit of being an economically sound way—as opposed to tariffs and subsidies—to boost capital-intensive U.S. manufacturing (e.g., a giant semiconductor fab). It’s honestly hard to find a serious wonk on the left, right, or in the center who opposes permanent expensing of at least some types of corporate investment, and most independent tax plans released prior to the OBBBA embraced it.

No surprise, then, that tax experts like Michel and the Tax Foundation’s Daniel Bunn, along with co-authors Alex Muresianu and William McBride, gleefully welcomed the OBBBA’s full expensing provisions.They write:

Immediate deductions for capital investment eliminates a tax penalty for capital investment, and permanent expensing has the most “bang for the buck” when it comes to economic growth. Those two provisions boost long-run GDP by 0.7 percent by eliminating that tax penalty and giving taxpayers the certainty needed to boost long-run investment.

2. Permanent extension of TJCA Individual tax provisions.

The second best thing in the OBBBA is simply its permanent extension of the TCJA’s individual income tax rates and brackets, as Bunn and his colleagues summarize:

The law also brings stability to the bones of the individual income tax. It secures permanent extension of the rates and brackets of the 2017 individual tax cuts, providing certainty for households and stability to the structure of the tax code. The law also permanently extends a larger standard deduction and a modified alternative minimum tax threshold. It also keeps some of the TCJA’s limits on some itemized deductions, such as for mortgage interest, and limits the value of itemized deductions for top earners. The standard deduction and limitations on itemized deductions have greatly simplified the tax code for millions of taxpayers.

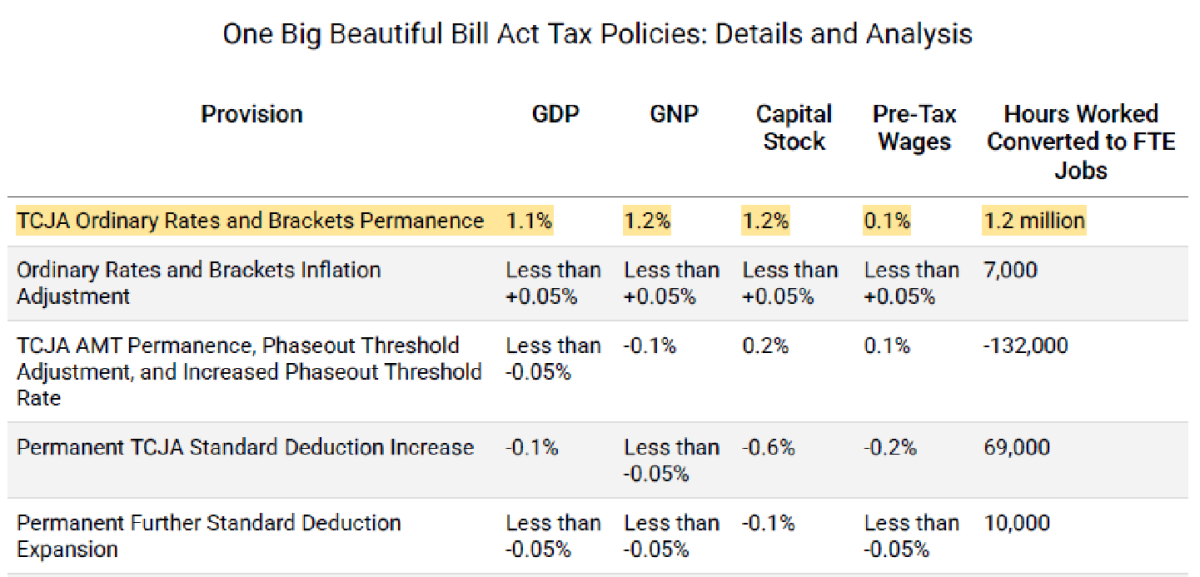

Providing permanently lower rates and a simplified tax structure will not only keep most Americans’ hard-earned dollars in their own pockets but also significantly boost economic growth. The Tax Foundation estimates, for example, that simply extending the TCJA tax rates will increase U.S. GDP and capital stock by more than 1 percent while also generating the equivalent of 1.2 million full-time jobs and modest wage increases.

Other nonpartisan estimates, such as those from the Congressional Budget Office and the Penn-Wharton Budget Model, show similarly positive economic effects from permanently extending the TCJA’s individual income tax provisions. And, as I discussed with Michel on the Cato podcast, the permanent extension also reduces uncertainty for tax filers across the spectrum, meaning peace of mind going into the next tax year and more confidence about spending and saving decisions down the road. We’ll discuss the extension’s budgetary issues in a bit, but—as just tax policy—this was good and welcome stuff.

(If only the tax writers had stopped here.)

3. Elimination of some IRA subsidies.

There are some real spending cuts in the OBBA, and my personal favorite in this regard is the law’s reduction of Inflation Reduction Act subsidies. As Bunn et al. summarize, these cuts constitute the law’s largest area of spending discipline:

The largest area of reform is the Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) green energy tax credits; both the House and Senate approaches raise about $500 billion over a decade, reducing the cost of the green energy credits by about half. Several IRA credits—like those for electric vehicles (EVs) and residential energy products— are repealed, while most others are restricted or phased out quicker.

Several of my fellow critics of the IRA’s subsidies correctly note that the OBBBA cuts didn’t go far enough in terms of reducing the subsidies’ size, scope, and complexity. (Most of the subsidies’ complicated rules on things like prevailing wages and apprenticeship requirements are still in place.) And more sensible IRA fans have—contra the online hysteria—celebrated that the OBBBA didn’t cut as much as they feared.

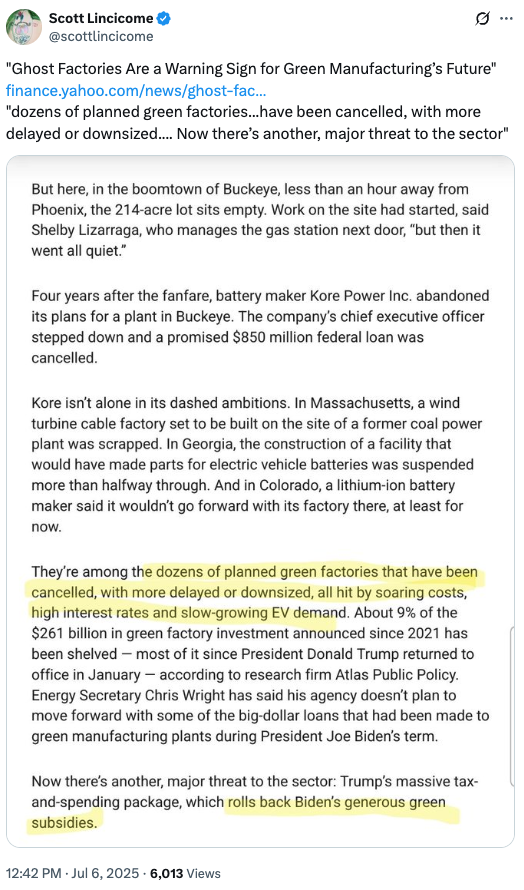

Still, the OBBBA’s reforms are a good, $500 billion start. As Capitolism has explained repeatedly, the IRA’s open-ended tax credits were extremely costly and, in many cases, both unnecessary and inefficient, while doing relatively little for the climate overall. Along with being bogged down by all those complicated (and protectionist) rules, the IRA subsidized mature technologies, encouraged loads of malinvestment, and—as we just saw following Republicans’ 2024 victories—increased economic and policy uncertainty in the U.S. energy market. We’ll discuss much of this in a forthcoming newsletter, but for now let me just give you two words: ghost factories.

Further IRA cuts are also (supposedly) on tap via stricter executive branch enforcement of the subsidies that remain—a promise that Trump reportedly made to House Republican budget hawks to get them to support the Senate’s scaled-back bill. Regardless, the OBBBA deserves credit for clawing back hundreds of billions of taxpayer dollars that should never have been spent (and that advocates claimed were politically untouchable). Indeed, if you combine the IRA cuts with permanent expensing, you begin to approach what Michel and I advised years ago as lower cost, less distortionary, and more effective ways to boost U.S. manufacturing and economic growth without all the political and economic problems that inevitably accompany U.S. industrial policy. Huzzah.

Sigh, the OBBBA’s Worst Stuff

Unfortunately, the OBBBA didn’t simply extend the TCJA and implement a few good tax and spending reforms. It did a lot of bad stuff that we’ll be dealing with for years to come.

1. The obvious deficit problem.

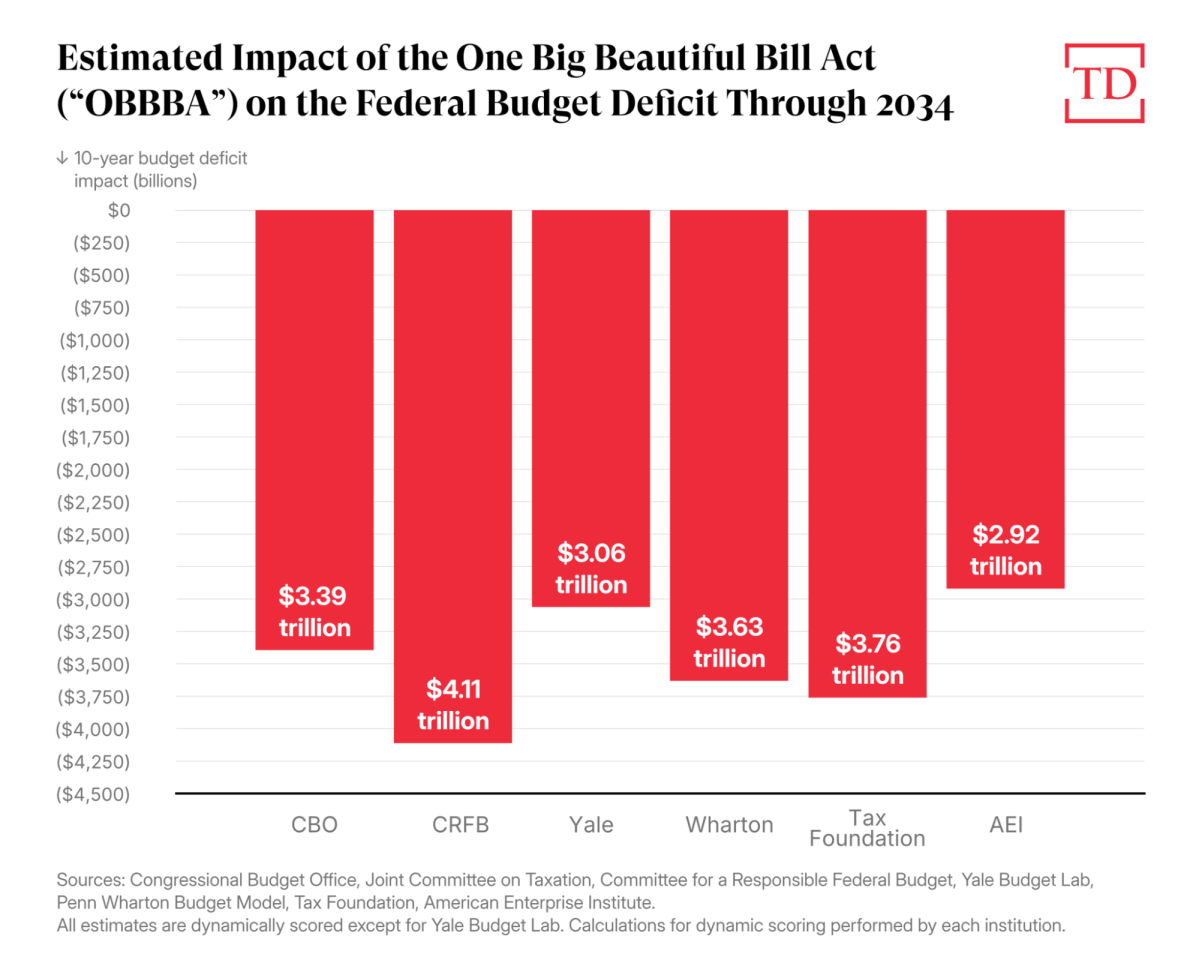

The law’s biggest problem, by far, is that it didn’t come anywhere close to matching tax cuts—good and bad—with spending cuts. Thus, as following chart shows, budget experts from across the political spectrum have calculated that the OBBBA will add trillions to the federal debt over the next 10 years:

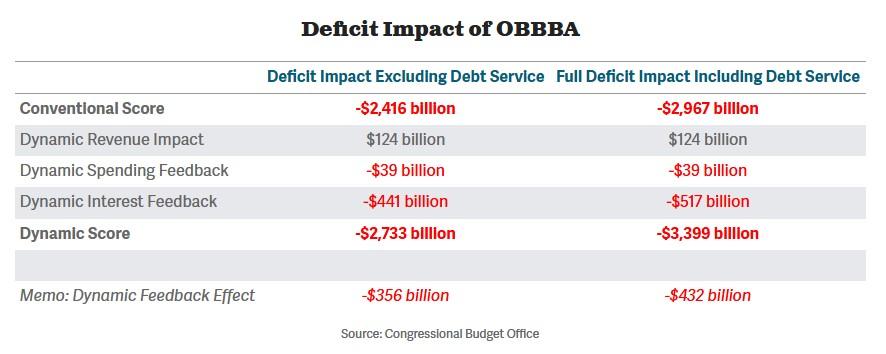

Notably, several of these analyses show that—unlike most tax cut bills—the OBBBA’s “dynamic” scores, which account for the laws’ economic effects, show future deficits that are actually higher than those in the static scores. That’s because, as the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget helpfully explained with respect to the CBO’s analysis, the new law’s massive debt load is predicted to increase U.S. interest rates and, in turn, interest costs on the federal debt by more than the revenue gains coming from the OBBBA’s spending cuts and economic growth:

Even these depressing deficit projections, unfortunately, could prove too rosy. As my Cato colleague Dominik Lett explained earlier this month, “realistic assumptions about economic growth, congressional extensions of tax giveaways or delays to spending reform, and the fiscal impact of mass deportations, the bill’s cost could soar past $6 trillion” instead of the measly $3 trillion to $4 trillion that most modelers predicted. The law, for example, reduces its 10-year deficit hit by expiring many of its tax gimmicks (see next section) before the end of the decade. Simply extending them—a likely outcome once millions of Americans get hooked on their new government sugar—would add another $1.4 trillion to the cost. The fiscal hole will get even deeper when you add the hit from the mass deportations that OBBBA funds. (Contrary to conservative conventional wisdom, the recent surge in immigrants was forecast to reduce the deficit by almost $900 billion.)

In short, the OBBBA’s main tax cuts were good but, because the law didn’t cut much spending, it remains—in Lett’s words—“a fiscal disaster.”

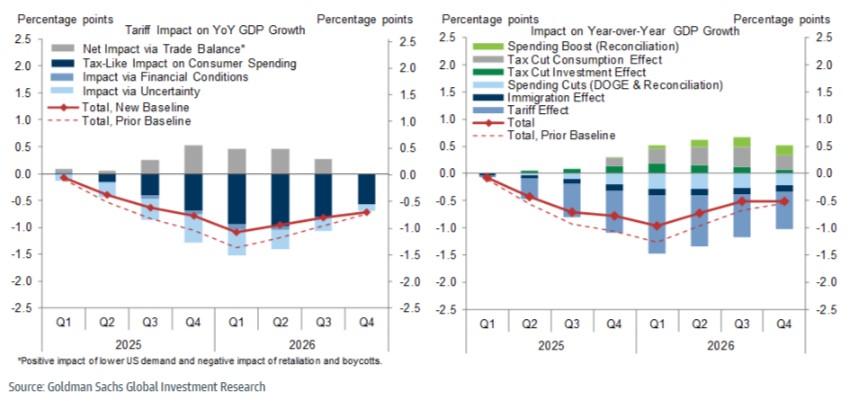

The numbers could be even worse still when you consider Trump’s tariffs, which will raise some revenue but will also lower U.S. business investment and economic growth more broadly. (And, as Republicans’ own “fantastical” OBBBA fiscal projections show, lower growth typically means less tax revenue.) For example, the Tax Foundation finds that the tariffs will undermine much of the investment boost that the expensing gains could provide. And Goldman Sachs estimated in June that Trump’s tariffs would more than offset the OBBB’s growth gains (and they’re certainly not alone):

In all this, the depressing story remains the same: almost no one in Congress is truly serious about cutting spending and getting the U.S. debt under control. For large majorities in both parties, it’s all free candy and fantasy math.

Until markets say it isn’t.

2. The political giveaways.

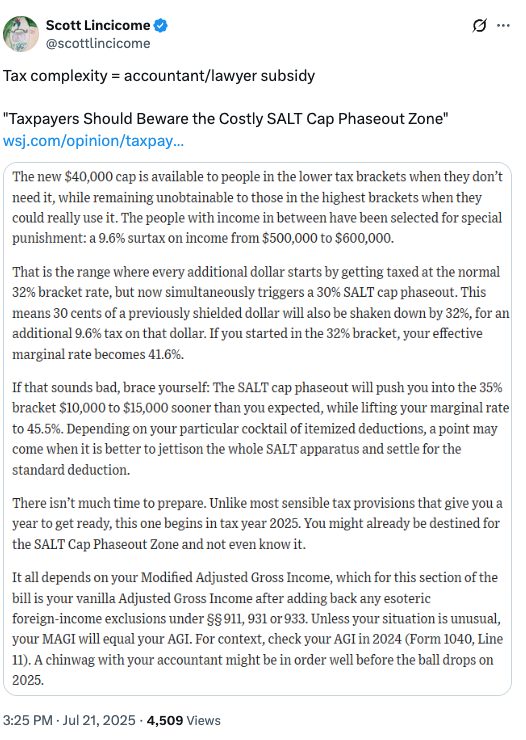

One of the reasons the law’s deficit numbers are so terrible is that it contains a boatload of new, purely political giveaways that complicate the tax code with little (if any) positive growth effects. The worst offenders in this regard are the four new tax carve-outs that Trump campaigned on—tax exclusions for tips and overtime, an additional senior deduction (aka “no tax on Social Security!”), and a tax exclusion for interest paid on auto loans—along with a massive expansion (from $10,000 to $40,000) of the state and local tax (SALT) deduction. Each one of these, Michel notes, “is poorly targeted, fiscally costly, and economically unjustified,” benefiting discrete special interest groups—e.g., wealthy homeowners in big-spending blue states or fancy-car lovers—while encouraging fraud and noncompliance.

Michel optimistically speculates that these temporary provisions could expire in a few years, thus dampening their terribleness, but—as already noted—there are reasons to doubt this outcome. (Breaking news: People love “free” money.) Yet, even without being extended, the giveaways are very costly: Just the overtime, tips, auto loans, and senior carve-outs will reduce revenues by more than $350 billion over the piddly four years they’re in effect. The temporary SALT expansion, meanwhile, will cost about $200 billion more.

Then there are all the other giveaways that made it into the final OBBBA to satisfy congressional holdouts or appease influential lobbyists and constituents, including:

- Increasing the maximum deduction available to Alaska Native whaling captains for whale hunting-related expenses (cost: $5 million).

- Revival of the “rum cover-over” program for U.S. territories’ rum industries, with indirect benefits to Louisiana’s molasses and cane sugar suppliers ($1.9 billion).

- A new tax break for sound recording productions in the United States ($153 million).

- An expansion of the small business stock gain exclusion ($17.2 billion).

- A tax break for “intangible drilling costs” for the oil and gas industry ($427 million)

- Payments to certain individuals who, umm, dye fuel ($6 million).

- A tax exemption for bonds issued by spaceports ($1 billion).

- A special tax break for real estate investment trusts ($3 billion).

And I’m sure there are many more that I’m missing.

The harms of these provisions extend beyond their budgetary cost and the grossness of using special government favors to buy off important politicians and voters. (Trump’s tips proposal, you’ll recall, was announced in Las Vegas to win/bribe hospitality workers’ votes.) As Bunn et al. mention, for example, each one of these porkers will require a “maze of new rules and compliance costs that in many cases likely outweigh potential tax benefits.” Here’s just one recent example of how convoluted the SALT break now is:

As the Wall Street Journal reports, the tips provisions will also be complicated (and subject to not-yet-determined rules published by Treasury). That’s all good for accountants and lawyers but is bad for the rest of us. And even people who clearly benefit will now spend hours of their time, if not some money too, to ensure they comply. These loopholes and carve-outs also mean more attempts to game the system—qualified workers suddenly getting paid via “tips,” for example—and, in turn, significant new enforcement costs for the government.

One of the TCJA’s biggest accomplishments was simplifying the convoluted U.S. tax code. The OBBBA’s costly tax giveaways go in precisely the opposite direction.

3. The brand new spending.

The final nail in the OBBBA’s coffin is its billions in new spending—beyond the aforementioned kickbacks. For example, the law increases by 50 percent the current CHIPS Act subsidy for new semiconductor manufacturing facilities, thus paying many manufacturers for investments they’ve already promised while also implicitly admitting that the current CHIPS Act subsidies weren’t big enough. The price tag: another $15 billion.

Contra the supposed “gutting” of the IRA, moreover, the OBBBA actually expands various energy subsidies, including the carbon dioxide sequestration credit ($14.2 billion) and the clean fuel production tax credit ($25.6 billion), while providing for special tax treatment for income from carbon capture, hydrogen storage, advanced nuclear, hydropower, and geothermal energy ($3.2 billion). It expands tax credits for low-income housing ($15.7 billion) and investment in low-income communities ($5.2 billion); for employer-provided child care, paid family and medical leave, and adoption ($5.4 billion total); and for contributions to scholarship-granting organizations ($25.9 billion). The law spends taxpayer money on a new “rural health transformation program” ($50 billion) and spends more on questionable military projects ($34 billion) and “opportunity zones” ($41 billion), while providing a tax exclusion for employer payments of student loans ($11.2 billion). Temporary IRA-style accounts for children—the ickily-named “Trump Accounts”—will add $16 billion more.

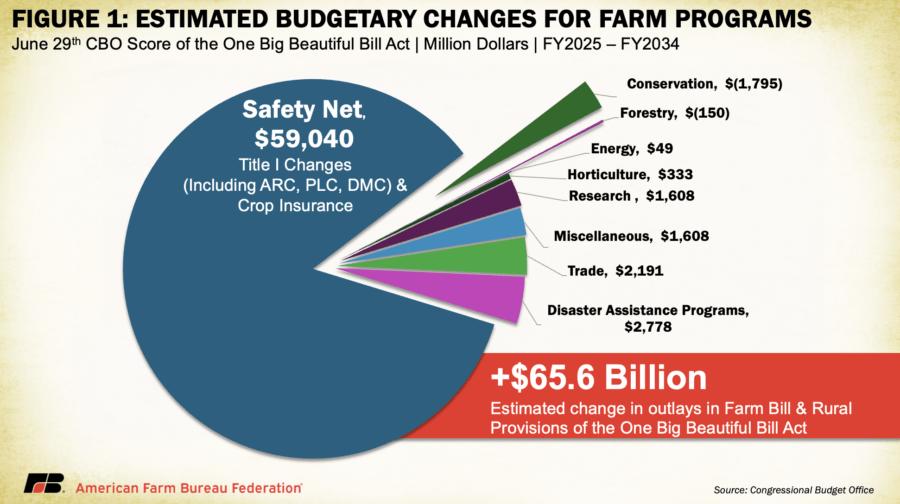

Finally, the OBBBA includes billions in additional handouts for American farmers. Along with that rural health fund, it provides a new tax break for sales of certain farmland ($7.3 billion). And it adds another $66 billion to our already bloated and distortionary farm subsidy programs, including both price supports and crop insurance:

Collectively, these OBBBA provisions total hundreds of billions of dollars in new federal spending—in law supposedly intended to cut it. They and other provisions like them prove once again that many Republicans in Congress like subsidies and industrial policy just fine—when they’re the ones in charge of it.

Summing It All Up

As is so often the case, political commentary on the OBBBA has typically exaggerated its costs and benefits—by extreme amounts. In reality, the OBBBA has a few good, pro-growth parts that, at least when it comes to expensing, find strong support from across the political spectrum. It also includes real spending cuts—including on things like Medicaid and SNAP that have long been considered politically untouchable. These and other reforms don’t go nearly far enough to tame the debt (and the federal Leviathan), but fiscal hawks in Congress and the policy community deserve some credit for moving the ball a few yards down the field—especially given where the OBBBA started and when all said ball has done for years now is go the other way. And, hey, maybe Michel is right that the law’s structure—with lots of permanent good stuff and temporary bad stuff—means U.S. tax policy will be even better a few years down the road, and that the OBBBA spending fights provide a roadmap for more reforms in the future.

The problem, alas, is that the OBBBA isn’t just the good parts or a few imperfect, albeit temporary, other provisions. It’s actively bad in all sorts of ways, risks policy getting even worse (and promises more legislative fights) in just a few years when all those tax handouts approach expiration, and throws several more logs onto our already blazing debt fire. Overall, I thus strongly agree with Michel that, were I in Congress (scary thought, I know), there’s no way I’d have voted for the thing.

The OBBBA also reveals a systemic problem that has infected so much U.S. economic policy these days, including Biden-era wins like the IRA: Thanks to sky-high partisanship and other political problems, today’s go-to vehicle for major U.S. economic policy reform is a gimmick-filled omnishamble bill rammed quickly through Congress in the cover of night via budget reconciliation, with all its procedural rules and limitations. It’s the usual legislative sausage-making dialed up to 11, with law and policy flipping radically every few years as Team Red or Team Blue takes over.

The results, alas, are just as bad as you’d expect.

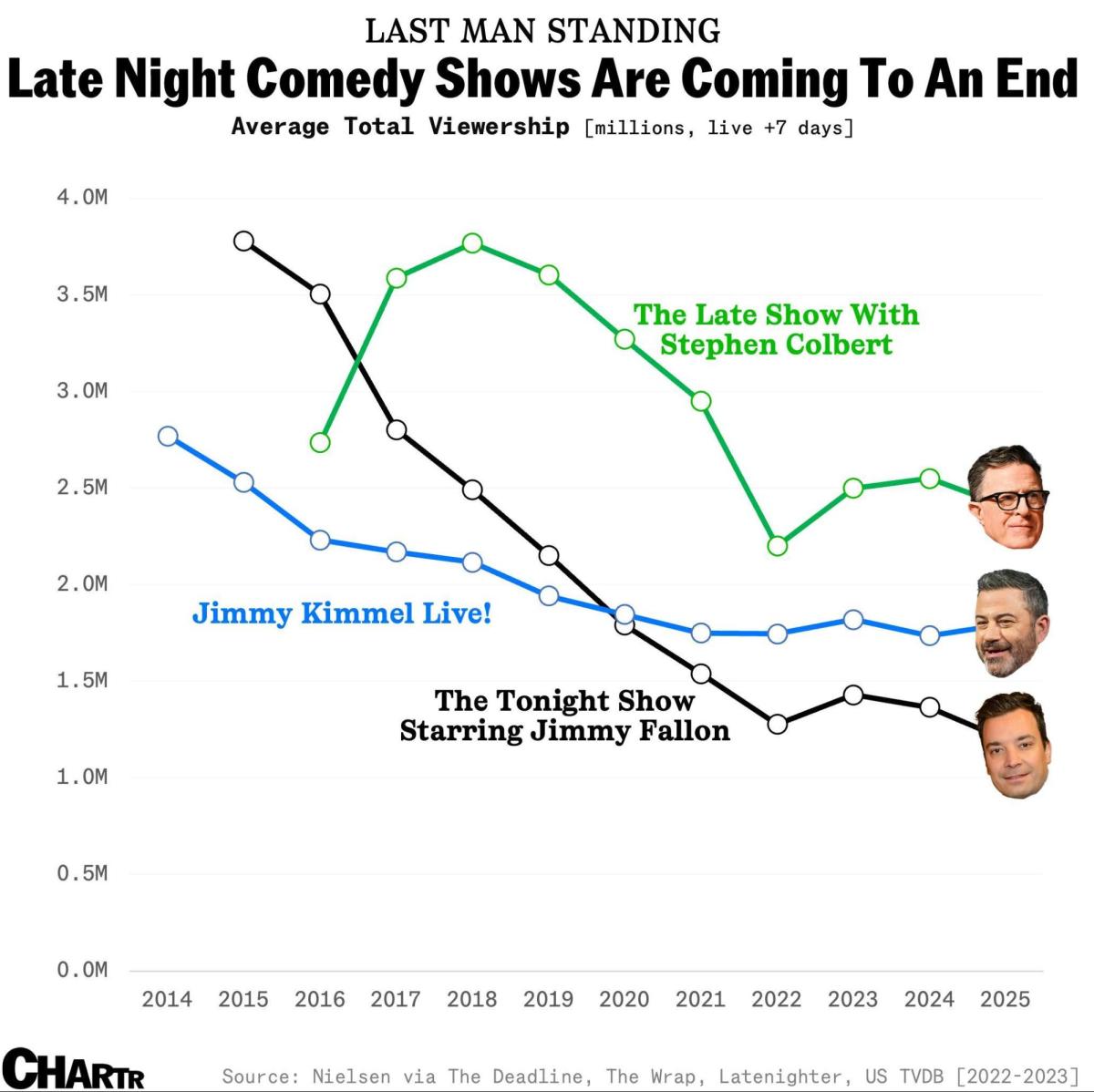

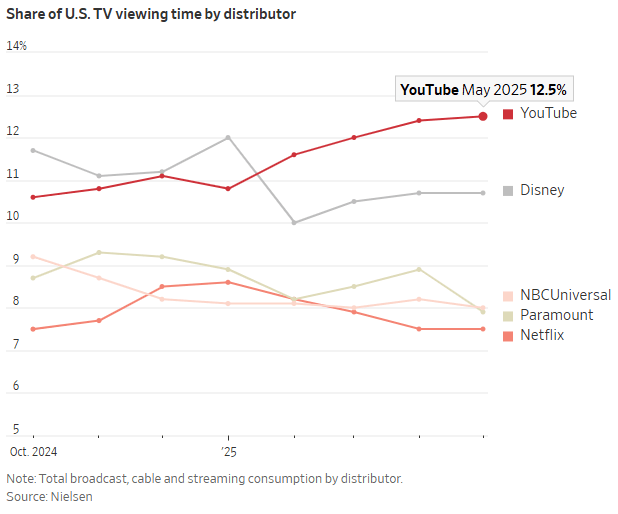

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.