Dear Capitolisters,

I was going to delight you this week with a deep dive into the moment’s most critical debate—who would win in a fight between Godzilla and King Kong—but so many other experts have already weighed in that my analysis seemed superfluous. Instead, today I’d like to celebrate the 30th edition of Capitolism by doing something that’s a little rare in the punditry game: revisiting past topics to see where things stand and how my initial assessments subsequently fared. So today we’ll look at three issues that I covered way back in the summer/fall of 2020—the CDC’s eviction moratorium, U.S. trade and tariff policy under a Biden administration, and the COVID-19 vaccines—to see how things have developed and where they might be headed.

And maybe to pat myself on the back a little too. Okay, fine, a lot. Anyway, let’s get started.

The CDC Eviction Moratorium

When the CDC’s moratorium on evictions was first implemented in September, it had all of the hallmarks of bad government policy. Since then, the federal government has extended the moratorium twice—it is now scheduled to expire at the end of June—and passed more than $46 billion in rental assistance for struggling tenants and their landlords. Both actions have muted the eviction moratorium’s impact, but several problems remain (pretty much as predicted):

Lawsuits. As chronicled by my Cato colleague Walter Olson, three federal courts have now ruled that the eviction violates the statute under which the action supposedly derives its authority. One of those courts—in Texas—“went further and struck down the measure as overstepping the federal government’s enumerated commerce power itself.” However, two other federal courts have upheld the CDC’s claim. As Olsen explains, “These differences make it likely that the litigation will continue to the circuit courts. At some point, the U.S. Supreme Court will likely be asked to resolve the question.”

Pain for landlords. As expected, the federal eviction moratorium and similar state-level actions imposed significant financial harm on numerous mom-and-pop landlords—who own own more than half (22 million units) of the nation’s rental supply and many of whom are today struggling to pay mortgages, taxes, maintenance, and other costs associated with their rental properties. The Urban Institute estimated that, as of January 2021, landlords were owed more than $57 billion in back rent and fees—and surely billions more as of today:

This financial hardship can have knock-on effects too. For example, here in North Carolina, it’s estimated that “for every 1% of renters not paying rent during a 6-month eviction moratorium, it leads to $21.9 million in decreased apartment rental income, which in turn leads to a $4 million decrease in property tax revenue.”

The aforementioned billions in federal rental assistance should help some landlords but certainly not all. In fact, the Urban Institute found last month that fewer than half of landlords (and even fewer tenants) were even aware of the program:

Another problem is that state eligibility rules often require both parties—tenant and landlord—to apply for rental assistance, but tenants have in many cases started ghosting their landlords. As a result of these and other impediments, only “sixty percent of single-family rental homeowners who are owed back rent received the necessary paperwork from their tenants, as required by the CDC, to receive the relief money.” As a result, some smaller landlords have been forced to sell their units or take on new debts to stay afloat.

Pain for tenants. Maybe, you might argue, this pain is necessary because of the pandemic and the benefit of the moratorium for low-income, unemployed renters. And surely, some renters have been helped. However, leaving the not-insignificant issue of property rights and the law aside, this view suffers from several flaws: First, there is evidence that many Americans who took advantage of the moratorium didn’t need it. For example, as the Seattle Times reports, “Of the nearly 212,000 Washington households who told Census surveyors they owed a month or more in back rent during the first half of March, 26,528 respondents, about 12%, said they hadn’t experienced unemployment or loss of income. More than 10,000 households with rent delinquencies reported annual household earnings of $100,000 or more.”

Second, not all deserving tenants have benefited: While their rent may (eventually) be covered by rental assistance, many tenants are still on the hook for late fees, while others have still been evicted when, for example, their leases were up (the perils of continuing a temporary program for almost year) and their landlords chose not to participate in the rental assistance program.

Finally, there is already some evidence that—as Econ 101 predicts—landlords are responding to the moratorium in ways that will make it more difficult for low-income tenants to find housing in the future. This includes tighter standards for approving new tenants and reducing rental housing supply (which raises rents):

With so many still waiting for relief, however, about a third of landlords said they will be forced to tighten standards when evaluating future rental applications, and 11% said they have already been forced to sell at least one of their properties.

In the current housing market, which is seeing very high demand and a record low number of homes for sale, homes listed by landlords will likely sell to owner occupants and evaporate from the rental housing stock. The pandemic-induced run on housing in the past year has caused the amount of rental stock to decrease by over a quarter of a million units. Rental housing is generally more affordable than ownership.

Instead of selling, other landlords are simply “warehousing” units until the moratorium ends:

One Manhattan landlord who spoke on condition of anonymity said eviction moratoriums, in addition to falling rental prices, were a second factor in his decision to warehouse roughly 15% of apartments in two buildings he owns in the Lower East Side.

Not only would the landlord have to offer a heavy discount on rent to get a new tenant, but under the eviction moratorium, the tenant could potentially stop paying rent for an indefinite period. “You’re kind of taking a double risk,” the landlord said, “so if you can afford to, why wouldn’t you just wait it out?”

It’ll be interesting to see what more rigorous economic analyses eventually say about how the CDC moratorium affected rental supply and low-income tenants, but these and other initial reports are (thus far) consistent with the research on rent control that I noted back in September. Maybe this kludge was the best we can do given the mayhem of the pandemic and 2020 election, but it’s certainly quite the hot mess today.

Tariffs and Biden Trade Policy

Biden’s trade policy has thus far—with one major and unfortunate exception—proceeded pretty much as expected. Trade policy has most definitely not been a priority for this administration so far, but when it is mentioned, it’s almost always in trade-skeptical and union-friendly (pardon me, “worker-centric”) ways.

For example, one of Biden’s first executive orders sought to tighten “Buy American” restrictions on federal government contracts—essentially narrowing the exceptions to federal procurement rules that require U.S. contracts to use domestic goods and services. Biden has also promised “Buy American” restrictions in his big “infrastructure” (scare quotes intentional) plan; assuming they’ll be similar to the mandates in Obama’s 2009 stimulus bill, these restrictions are likely to have similarly bad results (e.g., projects getting scuttled because they required Canadian materials or byzantine rules that confound small contractors). However, as of now, this is mostly just protectionist rhetoric, not a significant change in policy. Same goes for Biden’s review of “critical” supply chains, which we discussed a few weeks ago: His language is “Trumpy” and the review might eventually result in future trade actions, but it’s not yet worth getting worked up about.

The same, unfortunately, cannot be said for Trump’s tariffs, almost all of which remain in place as of today. The only good news so far has been the temporary four-month suspension of U.S., EU and U.K. tariffs that the governments put in place as a result of their longstanding World Trade Organization dispute over subsidies to Boeing and Airbus. Ironically, these are the only “Trump tariffs” that—while surely painful for exporters and consumers—are actually permitted by WTO rules and the United States’ obligations thereunder.

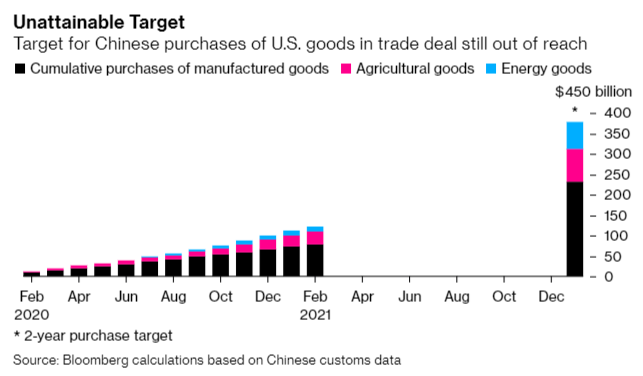

On the other hand, the other tariffs—the ones that are far more economically significant and legally dubious—haven’t budged. This includes, unsurprisingly, U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports (and China’s retaliatory tariffs on U.S. goods), which won’t be going anywhere anytime soon and may be around even longer if Congress (and the American public) remains deeply hostile toward the Chinese government and vice versa. Still, it’s worth reiterating that the Chinese tariffs have done nothing to change the long-term U.S.-China relationship, have affected total U.S.-China trade only modestly, and have most certainly failed to induce massive Chinese purchases of American goods:

But politics is what it is, so the tariffs stay.

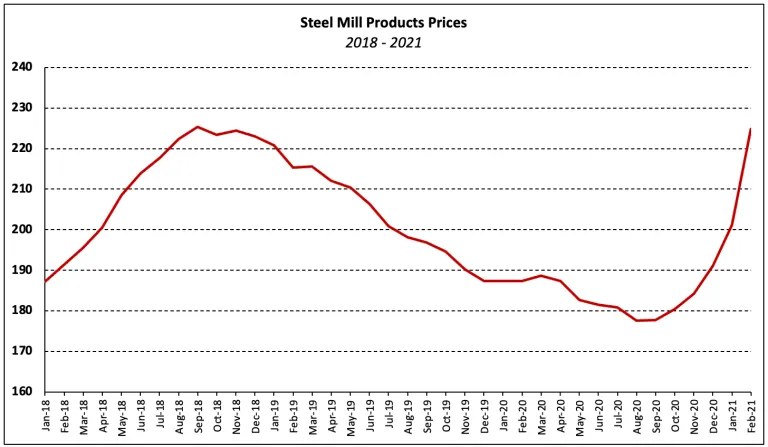

More surprisingly, the Biden administration has recently (and repeatedly) signaled support for Trump’s “national security” tariffs on steel and aluminum imports, including those on close allies like Japan and the EU, and even as raw materials costs in the United States have skyrocketed—threatening to derail the U.S. manufacturing recovery that Biden himself has promised.

That inaction is a shame, especially since—economic damage, foreign policy harms, and cronyism notwithstanding—there’s little evidence that the tariffs have actually been successful in boosting the U.S. steel industry. So American companies and consumers will keep suffering, and our allies will keep grousing (and retaliating). Bah.

Speaking of allies, the Biden administration—for all its talk about restoring the United States’ image around the world—has also underwhelmed at the WTO, lifting the Trump administration’s idiotic-but-mostly-symbolic block on seating a new director general but maintaining its idiotic-and-harmful block on seating new Appellate Body (basically the WTO’s supreme court) members and thus keeping the organization’s vaunted dispute settlement system hobbled (at best). Maybe things will loosen up in the future, but for now—it’s not great, Bob.

Vaccines

Finally, there is unabashedly good news on the vaccine front and some valuable lessons learned along the way. There’s honestly too much good news to share here, so I’ll just hit you with the highlights:

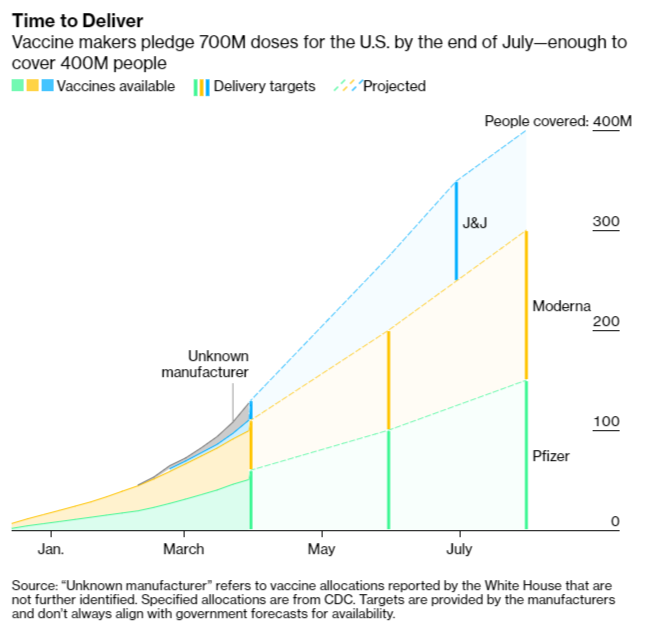

Production and supply of the three vaccines approved in the United States—BioNTech/Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson—has increased substantially thanks to a combination of added capacity and the companies’ internal adjustments. As a result, “the U.S. monthly output for the three authorized vaccines is expected to reach 132 million doses for March, nearly triple the 48 million in February,” and it should climb even higher this month and thereafter:

Things are so good right now on the supply front that we’re exporting unapproved AstraZeneca doses, and the unfortunate news of millions of Johnson & Johnson doses being spoiled at the Emergent BioSolutions facility in Maryland barely registered on our national pandemic angst-machine. (Thanks in no small part to imports.) Sure, I could (and will!) kvetch about the slow J&J approval or the AstraZeneca non-approval, but overall we are (as promised!) basically swimming in jabs at this point—a testament to all parties involved and especially the United States’ flexible and substantial industrial capabilities.

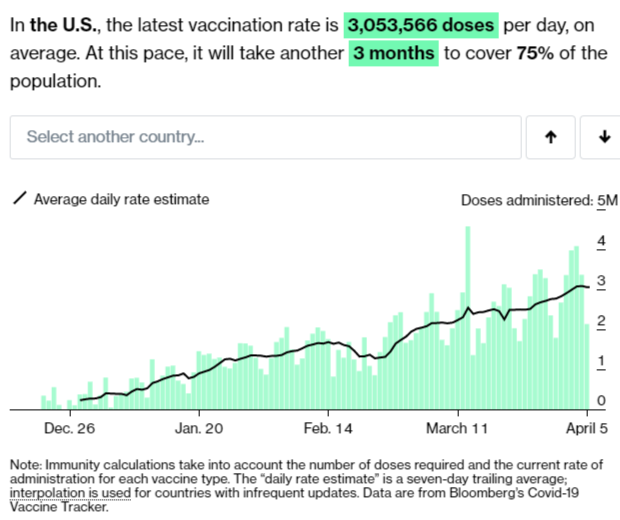

Things have improved just as dramatically on the distribution front, as the frustrating mistakes and bottlenecks of December and January have given way to a pretty efficient national jabbing machine, with single-day dosage totals hitting 4 million twice last week and the seven-day average above 3 million doses per day:

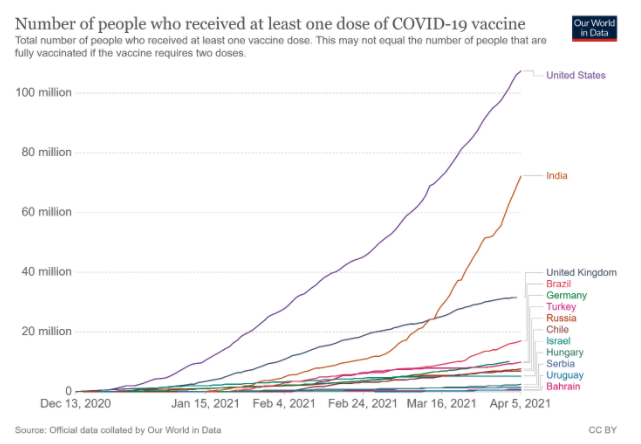

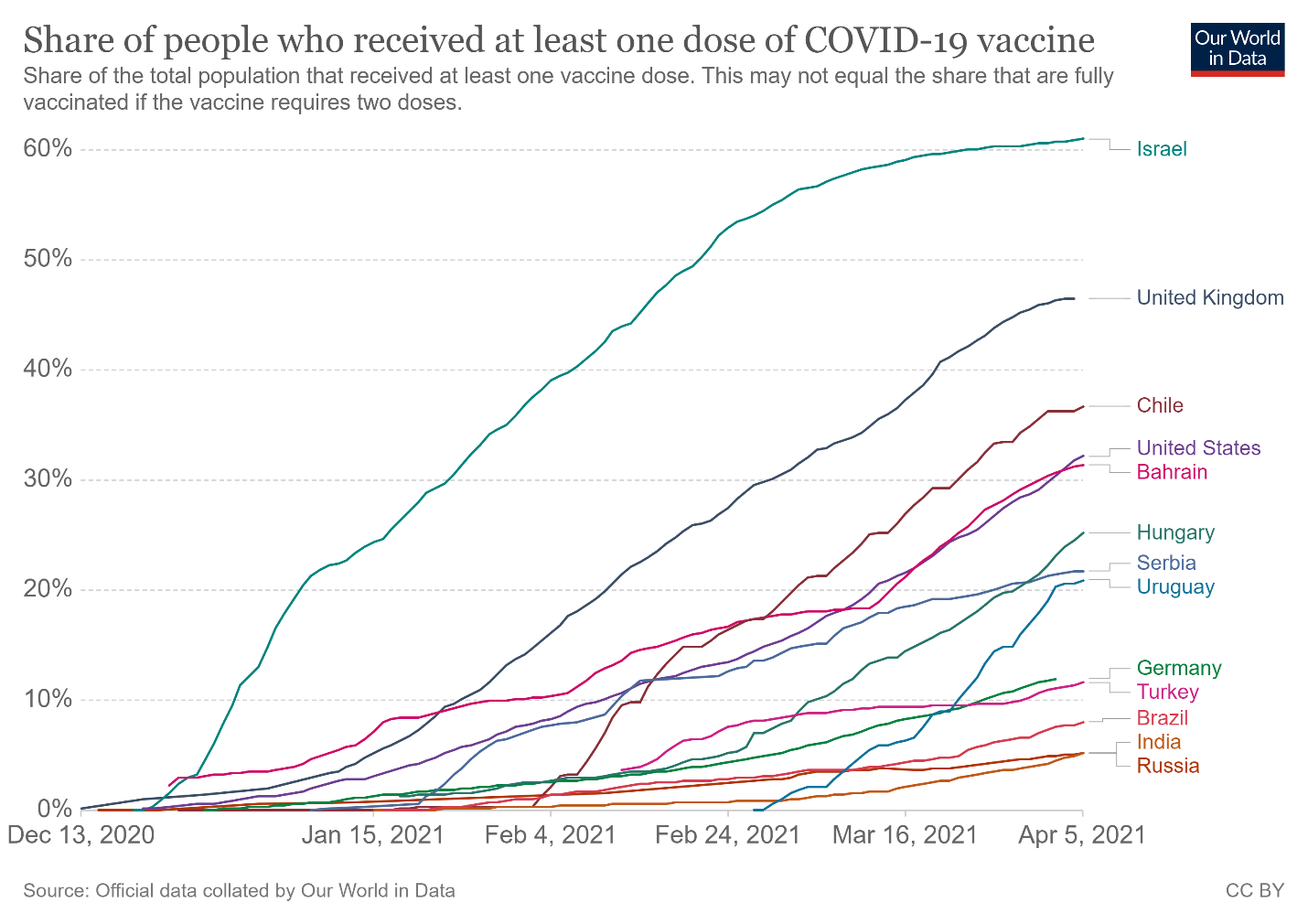

In terms of both total vaccines administered and share of population vaccinated, the U.S. is a global vaccine leader (though Israel and the U.K. deserve all the plaudits they get):

As Bloomberg documented Tuesday, the United States’ turnaround has stemmed from three main things (beyond additional supply): loosened eligibility restrictions, on-the-ground learning, and expanded, decentralized vaccination sites. On the latter two points, the Biden administration deserves credit for recently deciding to prioritize retail pharmacies over costly, bureaucratic FEMA mass vaccination sites:

The vaccination hubs, which are run by FEMA and staffed in part by National Guard troops and other Pentagon personnel, have administered just 1.7 million doses since the beginning of February. Over the last two weeks, the sites gave about 67,000 shots a day, according to a series of internal FEMA briefing documents and data sets obtained by POLITICO. That’s roughly 2.5 percent of all doses administered nationwide during the same period, according to data published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

By comparison, the federal retail pharmacy program reported March 11 it had administered nearly 1 million doses over a single day. Over the course of the next four days, the program’s pharmacies administered more than 5 million more doses, according to the federal vaccination data obtained by POLITICO….

“We see enormous potential with the retail pharmacy program,” one senior Biden health official said. “More and more pharmacies sign up to distribute each day.”

One can quibble with some of the details here and there (see next paragraph!), but overall the U.S. vaccination effort is going well, and the economy has started to reflect that optimism—even before the American Rescue Plan checks hit Americans’ bank accounts.

Finally, there is increasing evidence that many of the unconventional ideas regarding vaccines and COVID-19 more broadly have turned out to be (mostly) correct. In this regard, I recommend this Ezra Klein piece on George Mason University’s Alex Tabarrok, who has been a leader in pushing “radical” ideas—especially “first doses first”—that seem far less radical in retrospect and have been embraced by numerous public health experts (one recent headline: “U.K. Vaccination Puts U.S. to Shame”). My Cato colleague Ryan Bourne helpfully summarized some of Tabarrok’s many good ideas and why (in his view and mine) they’ve worked:

Underlying all Tabarrok’s COVID-19 policy advocacy is the view that the pandemic’s total welfare costs are inevitably massive and so measures that end it or severely mitigate it almost always pay for themselves. Overly precautionary behavior on behalf of regulators, or else Congress focusing on relief spending rather than speeding up vaccine manufacture or distribution, therefore come with huge, unjustifiable opportunity costs.

A more interesting question than “Is Alex Tabarrok right?” then is “Why is Alex Tabarrok right?” Tabarrok has chosen the right battles as a libertarian in this pandemic because he approaches the issues using a sound economics toolkit. That willingness to apply economics to this novel scenario, and use its methods of defining counterfactuals, weighing up of costs and benefits, acknowledging trade‐offs, thinking on the margin, and analyzing incentives, means he can acknowledge where the biggest gains to human welfare can be made, unencumbered by convention, politics, or culture wars.

As a result of using these frameworks, Tabarrok has led the way in advocating: the green‐lighting of at‐home, cheap testing; replacing lockdown regulations with “smart” reopening; using market‐set prices to incentivize production of important goods and services; abandoning mutually destructive sicken‐thy‐neighbor trade policies; making big advanced purchase orders for vaccines; allowing vaccine human challenge trials for the young and healthy; allowing a wider spacing of vaccine doses to achieve greater communal protection sooner; and, of course, approving the AstraZeneca vaccine.

If we had adopted just a few of the policies he’s advocated, we’d have averted much suffering, and we could even now!

As I’ve said a few times around here, it’s probably too late for the United States to shift gears on vaccine strategy, but there’s still (unfortunately) time for other countries to learn these lessons—and for U.S. authorities to consider them when preparing for the next pandemic or other national emergency.

Let’s hope they do.

P.S. A quick housekeeping note: Many readers have asked about sharing an occasional Capitolism newsletter with their contacts. On this question, I toe the Company Line: Please feel free, as long as you don’t make it a habit.

Chart of the Week

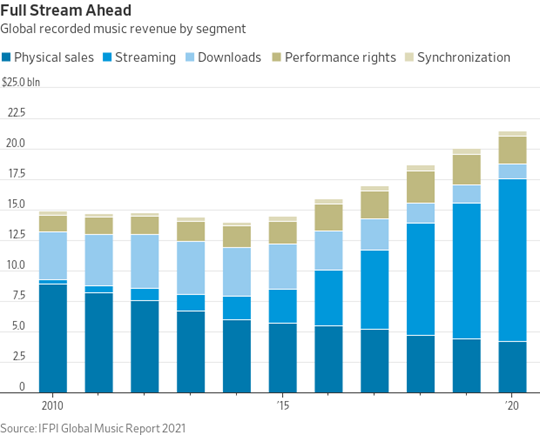

Creative destruction (link):

Bonus Chart of the Week

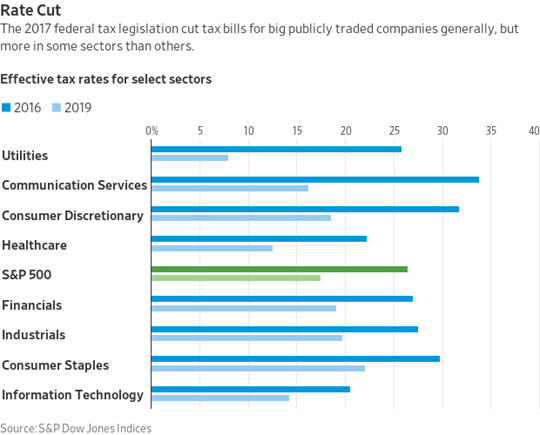

More on corporate taxes (link)

The Links

Me, on Buy American, pandemic supply chains (podcast), NC supply chains (podcast), and social capital (podcast)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.