Dear Capitolisters,

As many conservatives and libertarians know all too well, “bipartisanship” is one of the most annoyingly misunderstood concepts in American politics and media. Yes, sure, it’s fine and good when Congress approves a good bill with lots of votes from both major political parties, but good law can get made via party-line votes and bad legislation can sail quickly through the legislative process with nary a peep of opposition. Indeed, some of the worst laws on the books were enacted with lots of R and D votes, and—frustratingly—with advocates using that bipartisanship as a useful shield against legitimate criticism.

There’s perhaps no better example of this kind of bipartisanship—the bad kind—than the farm bill, which Congress is again considering (as it does every five years) and will almost surely pass later this year with overwhelming bipartisan support. On its face, the farm bill is a sprawling, $1 trillion piece of legislation ostensibly about U.S. agriculture policy; but it’s really about a lot more than that—and it’s a testament to how bad policy gets made in Washington, too often accompanied by a harmonious chorus of happy Republicans and Democrats.

What’s in the Farm Bill?

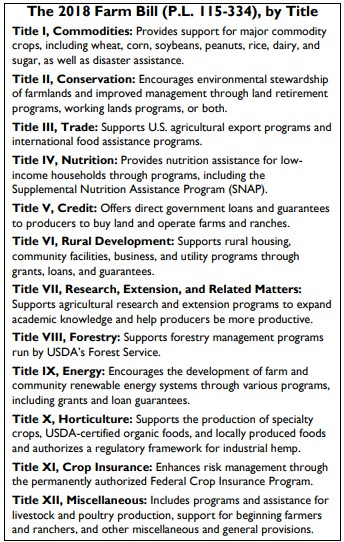

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) provides a good summary of the farm bill’s quinquennial renewal process and content. As you can see from the following table on what was in the 2018 law, it covers a lot:

For our purposes, however, we can put most of this into one of four buckets: farm subsidies, nutrition assistance (SNAP), trade, and conservation. There’s other stuff in there too, of course, but these are the big ones.

In a previous newsletter, I discussed U.S. farm subsidies generally, but didn’t really dive into all the ways that the U.S. government supports American farmers. My Cato colleague Chris Edwards helpfully does that heavy lifting in a new briefing paper, noting that “the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) runs more than 150 programs that provide direct subsidies and indirect support to farm businesses,” with most direct subsidies going to “large producers of corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, and rice—not for livestock producers or fruit and vegetable growers.” He then breaks down the main direct subsidy programs and payment levels involved:

- Crop insurance, under which the feds subsidize farmers’ insurance premiums and pay private insurers’ administrative costs (about $10 billion a year).

- Agriculture risk coverage (ARC), which subsidizes farmers if revenues fall below a certain level (0-$6 billion).

- Price loss coverage (PLC), which pays farmers if their crops’ national prices fall below a government “reference price” (0-$5 billion).

- Conservation programs, which pay farmers to improve their land in various ways ($5 billion).

As he notes, the farm bill also provides special subsidies for certain commodities, as well as billions more in marketing, trade, research, and other types of support, mainly through the USDA. Congress has also authorized billions in ad hoc emergency spending over the years, most recently during the pandemic. But most of this stuff happens through the farm bill.

And little of it is good.

Spending, and Spending, and More Spending

Start with the spending. The types of subsidies doled out via the farm bill change over time, but the level of support has consistently remained in the tens of billions of dollars each year, with disaster assistance almost always a small fraction of the total tab:

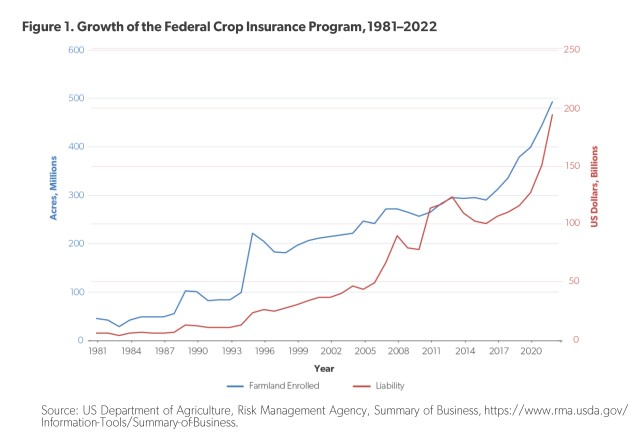

As indicated in the chart above, the big recent changes to U.S. agriculture subsidy levels have come from two things, both of which are governed by the farm bill. First, successive congressional expansions of federally subsidized crop insurance has caused the program to expand dramatically, in terms of acreage covered, total liability, and cost to the government:

As documented by the Government Accountability Office, one reason for this expansion is that subsidized crop insurance doesn’t limit eligibility to farmers below a certain income level. The GAO found that one wealthy farmer “received an average of $1.2 million annually in premium subsidies,” while lower income participants received only $7,480 over the same period. GAO also found that a provision in the 2014 farm bill can generate payouts to insurance companies that were well above what would be expected under market conditions.

Second, the farm bill reauthorizes legal provisions that give the executive branch wide discretion to increase spending levels in certain circumstances. Most notoriously, the Trump administration doled out about $25 billion in “market facilitation program” payments to U.S. exporters (farmers and ranchers) hurt—via other nations’ utterly predictable retaliatory tariffs—by the trade wars that he started. According to a recent report, several red states that voted for Trump in 2016—especially in the Midwest—actually came out ahead from these unscheduled, totally avoidable subsidies (though most states lost on net). The farm bill—and by extension Congress—disciplined none of this.

Poorly Targeted ‘Creep’

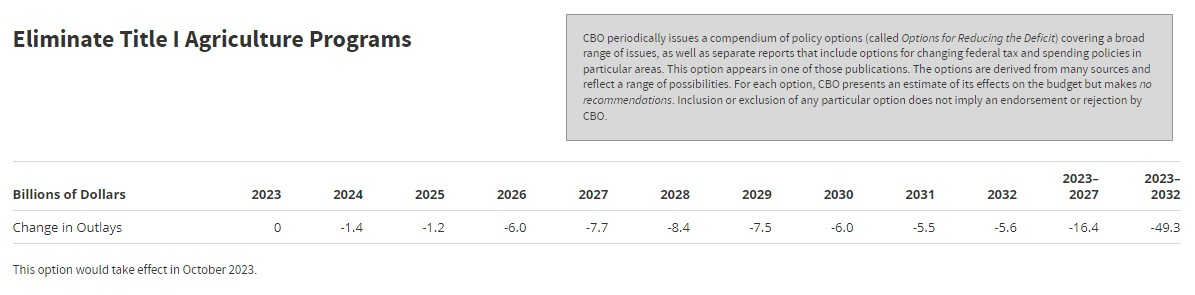

In the grand scheme of America’s budget problems, these spending totals may seem insignificant in isolation. According to a 2022 Congressional Budget Office report, for example, eliminating just the farm bill’s “Title I” subsidies would save a few billion taxpayer dollars per year (almost $50 billion over the next decade):

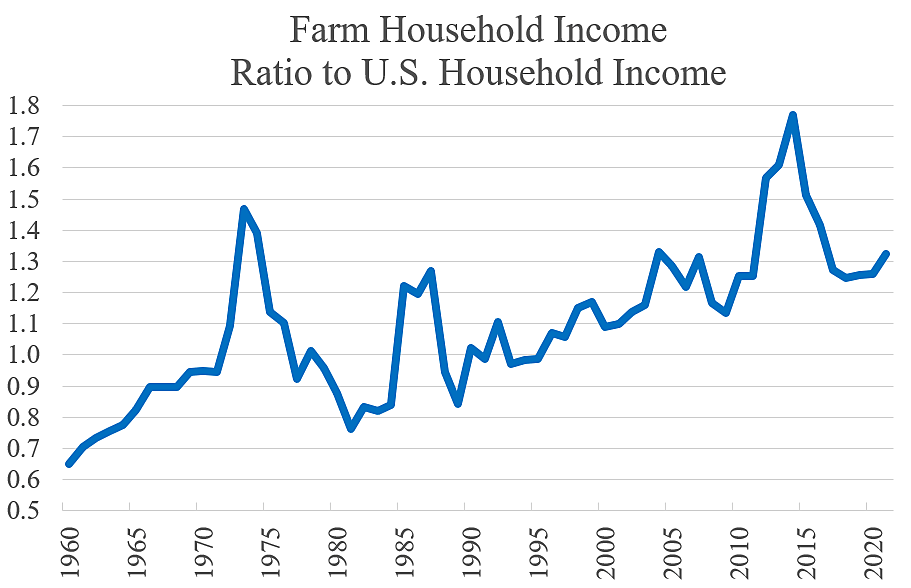

That’s not nothing, of course, but it also won’t plug the United States’ gaping fiscal hole. Instead, the bigger problem with the farm bill’s subsidies is that they are incredibly wasteful, overwhelmingly supporting people who don’t need them and for whom the original U.S. farm subsidies were never intended. As AEI’s Vince Smith documents, farm subsidies were introduced in the Great Depression under what was back then a somewhat justifiable anti-poverty premise: to guarantee some level of income to farmers when markets collapsed in the 1930s, especially because American farm family incomes back then “were measurably lower than the national average.”

Today, however, such claims are a joke. As Edwards explains in his paper and a separate blog post, American farmers these days are actually richer on average than other Americans: “In 1960, farm households earned 65 percent of the incomes of all U.S. households, on average, but by 2021 they were earning 32 percent more. In 2021, the average income of farm households was $135,281, which compared to the average for all U.S. households of $102,316.”

Today, only 2 percent of farm households have below-median wealth levels. Yet most farm subsidies go to the largest and wealthiest farmers, not those potentially in need of assistance. Edwards notes, for example, one study finding that 60 percent of all crop insurance, ARC, and PLC subsidies went to the largest 10 percent of farms, with that group also receiving much bigger crop insurance subsidies on average. USDA found in 2015 that “half of crop payments, crop insurance subsidies, and working‐lands conservation subsidies went to households with incomes of more than $140,000, an income level that compared to a median of $56,516 for all U.S. households that year.” Even the ultra-rich get in on the act: “50 people on the Forbes 400 list of the wealthiest Americans received farm subsidies between 1995 and 2014.”

A new Environmental Working Group (EWG) report corroborates these findings. “Between 1995 and 2021,” the report reads, “the top 10 percent of farm subsidy recipients that received the largest payments received over 78 percent of commodity program subsidies, and the top 1 percent received 27 percent of payments.” None of this is surprising because, as the EWG explains, it’s how the subsidies are designed: “Payments are made based on acreage or production, so the farms with the most acres or most crops produced get the largest payments.”

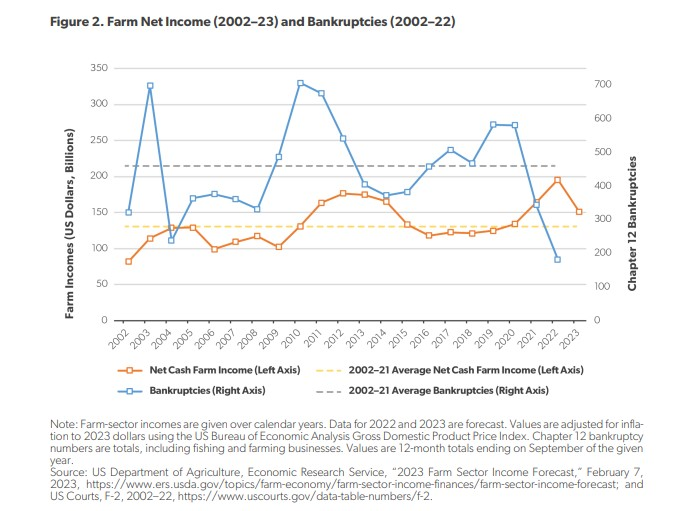

AEI’s Smith adds that American farmers are at no special financial risk that might necessitate consistent, long-term government support—especially these days, when incomes are high and bankruptcies are historically low. As he notes, “Even if some form of a farm safety-net program might be needed to stabilize the agricultural sector in difficult years, an argument for which there is little empirical support, the program should not be paying out large subsidies in financial good times.” Yet it does—and farmers are today gunning for more.

It’s also important to note that direct subsidies aren’t the only U.S. fiscal policies that benefit American farmers. Edwards documents that almost all farmers get better tax treatment than most non-farmers because of how their businesses are structured (allowing them to file under the individual income tax) and because more than a dozen provisions in U.S. tax law allow farmers to report losses on their tax returns and thus reduce their overall tax bill, including on non-farm incomes.

Put it all together, and you can see why Smith rightly concludes that “any evidence-based antipoverty rationales for these programs have effectively disappeared.”

Other, post hoc justifications for U.S. farm subsidies also ring hollow. Smith adds in his paper and elsewhere, for example, that a common excuse for the farm bill—food security—is “fundamentally nonsensical.” American farmers are financially healthy; U.S. agribusiness companies are world-class; as a land-rich nation, the United States has substantial comparative advantages in agriculture; and U.S. farmland is almost always sold to even more efficient farmers. There’s also little relationship between inflation-adjusted U.S. subsidy levels, which have fluctuated significantly over time, and U.S. food prices, which (until recently) have steadily declined. And there’s little evidence that farming is inherently any riskier than running many other types of private businesses, such as energy or tech, and any risk that does exist is mitigated by farmers’ increasing share of non-farm income – and could be further mitigated by an unsubsidized insurance market.

Rent Seeking and Cronyism

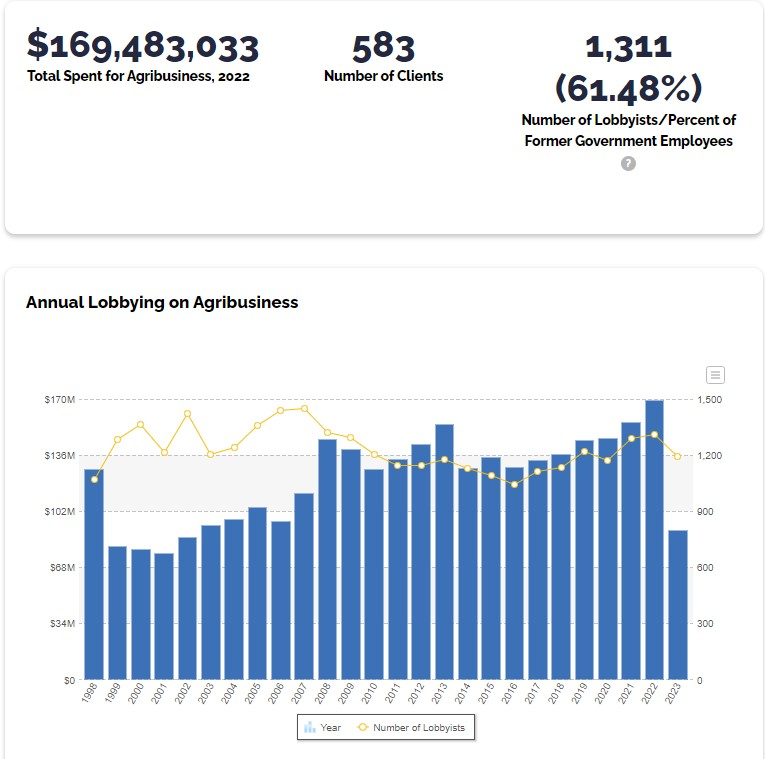

The farm bill’s substantial cost, wasteful scope, and stubborn persistence in the face of changing U.S. and global agriculture markets (some programs, such as dairy price supports and crop insurance, date back to the New Deal) is a testament to the influence of interest group lobbying and good ol’ pork barrel politics. Most obviously, U.S. agribusiness, the American Farm Bureau, and related U.S. farm interest groups spend whopping sums annually to ensure that members know and embrace their priorities:

Perhaps the most notorious example of this influence is the U.S. sugar industry, which we covered in a previous newsletter: “Even though sugar represents 1.36 percent of the value of all crop production, it represents roughly a 55 percent share of crop production lobbying and 9.66 percent of agribusiness lobbying money. … U.S. sugar producers and processors in 2020 donated more than $6 million in campaign cash to congressional members, Republicans and Democrats, from 48 different states (most of which aren’t home to beet or cane production but are home to members of the House and Senate agriculture committees).” But Big Sugar surely isn’t alone: It’s joined by Big Dairy, Big Peanut, Big Wheat, Big Corn, and several others. The last time the farm bill was up for renewal (in 2018), in fact, it was the fourth most lobbied bill of the year, with 602 unique organizations having registered to lobby on the legislation. As the campaign finance group Open Secrets documented late that same year, these efforts proved successful:

Passed overwhelmingly by Congress this week and expected to be signed by President Donald Trump, the new $867 billion Farm Bill has lobbyists’ fingerprints all over it, as is tradition. …

Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) was one of 13 Republican senators to vote against the bill. The senior senator was irate on the Senate floor Tuesday, criticizing the “dark rooms of conference committee meetings” that removed his Senate-approved amendment to lower the cap on subsidies to high-income farms. Another provision to remove a loophole that allows agri-businesses to designate family members as “farm managers” that can receive up to $125,000 in subsidies, even if they don’t work on the farm, was also removed. …

Grassley noted the same thing happened in 2014 when a similar amendment of his passed the House and Senate but was removed in conference committees. Grassley is a member of the Agriculture Committee but was not selected to join the conference committee.

What lobbyists were able to accomplish in the so-called “dark rooms” will never be entirely clear, even when fourth-quarter lobbying disclosures are released. But critics from both ends of the ideological spectrum say the bill reinforces a corporate welfare status quo.

This season’s farm bill lobbying disclosures are still in their early days, but interest groups are lining up once again.

Meanwhile, the congressional committees with primary jurisdiction over the farm bill—the House Committee on Agriculture and the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry—are overwhelmingly populated by members from farm-heavy areas of the country. Many of them are (or were) farmers themselves or have worked hard to get the assignment because of the committee’s value to their constituents. Of course, these members can provide useful insights into the U.S. farm economy, but the biases and downsides are just as obvious. Indeed, trade industry websites are littered with puff pieces about members of both parties who have spent decades in Congress working to deliver rents to their constituents and getting rewarded—sometimes literally!—for doing so. Even worse, Edwards notes, is that “Congress and its farm committees include many members who receive farm subsidies and thus have an obvious conflict of interest on farm votes. There are 25 current members of the House—including 8 members on the House Agriculture Committee—who have received federal farm subsidies.”

This is hardly a way to make good policy.

Finally, the farm bill’s sheer size and scope fuels further interest among groups affected by the policies (and usually vying for their share of the pie), thus creating a perverse cycle of rent seeking, rent delivery, and even more rent seeking. As the CRS puts it, “In recent years, more stakeholders have become involved in the debate on farm bills, including national farm groups; commodity associations; state organizations; nutrition and public health officials; and advocacy groups representing conservation, recreation, rural development, faith-based interests, local food systems, and organic production. These factors can contribute to increased interest in the allocation of funds provided in a farm bill.”

I bet they do.

Logrolling and ‘Omnibusing’

The farm bill’s size and design further confound reform efforts—and quite intentionally so. Most famously, the legislation has since the 1970s coupled all the subsidies with nutritional assistance (SNAP), the latter of which today makes up more than 75 percent of all farm bill spending:

Thus, farm subsidies garner support from anti-corporate Democrats, while SNAP benefits are passed by welfare-reforming Republicans—a textbook example of congressional “logrolling.” The diverse nature of the subsidies themselves further amplifies all the back-scratching:

In his book on government dysfunction, MSNBC host and former congressman Joe Scarborough described the logrolling frenzy leading to the passage of the 2002 farm bill, which he called the “largest corporate welfare scam in history.” He discussed how dairy subsidies were demanded by members from Maine, Pennsylvania, and Vermont, peanut subsidies were demanded by members from Virginia, Alabama, and Georgia, and sugar subsidies were demanded by members from Florida. The logrolling continued for cotton, wheat, wool, mohair, and many other products.

Scarborough concluded, “Standing alone, not one of these corporate welfare measures could survive the bright light of public scrutiny.”

Or, as the CRS puts it, “The omnibus nature of the farm bill can create broad coalitions of support among sometimes conflicting interests for policies that individually might have greater difficulty achieving majority support in the legislative process.” The interests win, and we all lose.

Unsurprisingly, reform efforts to decouple the subsidies and SNAP have been met with strong resistance by the American farm lobby:

A more recent ‘big idea’ in farm policy emerged in the two years leading up to passage of the 2014 Farm Bill—splitting the nutrition title from the remaining farm bill items and treating them as separate legislation. Indeed, the first farm bill passed by the House of Representatives in 2013 eliminated the nutrition title leaving it for a separate bill. That particular idea has not gained much momentum in the subsequent ten years. In fact, a stated priority of many farm groups in 2023 is to maintain the current “farm and food” format of the bill with the nutrition title and its objectives intact.

The bill’s complexity adds another hurdle to reform—something the U.S. government understands well in other contexts. The 2018 law, for example, weighed in at a portly 530 pages, consisted of 503 different sections (14 titles and 51 subtitles), and was the result of a process that included 316 different congressional actions, 369 amendments, and 76 related bills. Such size and complexity—not to mention the actual text (reference price calculations, etc.) and related measures—makes the farm bill incomprehensible to all but the most seasoned wonk, legislative staffer, or lobbyist. Even then, much of the final substance will be hidden from members like Sen. Grassley (see above) until right before the giant omnibus bill is passed.

It’s legislative sausage-making at its worst.

So Much Bureaucracy

Complex programs inevitably require numerous bureaucrats to implement them, and the farm bill is no exception: USDA today has more than 100,000 employees, in 29 agencies and 4,500 locations here and abroad (2,300 in the U.S. alone). Granted, a lot of these folks are in the forest service (e.g. park rangers) or handle health and safety inspections, but an eye-popping 30,000-plus just dole out farm subsidies. That’s nuts.

Indeed, the agency and its programs are so big and convoluted that the USDA has ended up subsidizing itself: “The financial institution that received the most money was a division of the USDA—its [Farm Service Agency] got $346.7 million, or 11 percent of payments to financial institutions, and just under 1 percent of all farm subsidy payments. Dairy programs were responsible for the most money sent to the FSA, with the PLC a close second program.”

You can’t make it up, folks.

Lack of Transparency

As already noted, much of what becomes law is kept from public eyes until the very last second. But the farm bill’s transparency problems can also continue long after it becomes law. According to the EWG, for example, “The USDA has become significantly less transparent about how it discloses [subsidy] payments, obscuring who has received some $3.1 billion” in taxpayer funds. In particular, USDA used to release the names of subsidy recipients in response to the group’s Freedom of Information Act requests, but—after 22 years—ditched that standard procedure and, without explanation, moved to providing only the name of the bank or financial institution involved, even after EWG has appealed the non-disclosure. Why do this? Well, as the group notes, this makes it “impossible to know how many people may be getting such payments, what they’re growing, and other key information”—information that could be used to discredit the subsidies. U.S. food aid programs—discussed next—suffer from similar transparency problems, hiding from taxpayers and policymakers the true extent of their effects.

High Non-Budgetary Costs

As we discussed last time, the farm bill generates all sorts of costs beyond just the budgetary hit and political dysfunction. This includes market distortions (shortages, gluts, etc.), environmental degradation, unhealthy diets, trade conflicts, and harm to poor countries. This last one, as Edwards explains, includes billions for old, in-kind “food aid” programs that most other countries have abandoned because they actually undermine poor countries’ farm sectors and food supplies.

In particular, by shipping U.S. food abroad instead of just sending money, these programs are notoriously slow, convoluted, and expensive, and they can actually displace local food production. Adding insult to injury, the Cargo Preference Act requires that much of this “assistance” be shipped on U.S.-flagged vessels, which are more costly than foreign-flagged vessels. Thus, the GAO has found that “cargo preference rules increase shipping costs of food aid by an average 31 percent.” (Yes, this stuff is pushed by the same folks who love the Jones Act.)

For these and other reasons, the Bush, Obama, and Trump administrations have all proposed reforms to U.S. food aid programs. Yet, thanks to the farm and shipping lobbies, they persist. Blech.

Summing It All Up

So the farm bill has expanded well beyond its original purpose, funnels billions of taxpayer dollars to wealthy Americans and companies that don’t need it, imposes economic, social, and geopolitical costs, and—thanks to quintessential Beltway politics—resists both pragmatic and fundamental reforms. Indeed, it may very well be that lack of reform that’s the most galling part of it all: Not only are there obvious small-ball moves that could, at the very least, keep bajillionaires from cashing U.S. farm subsidy checks, limit government assistance to real emergency situations, or stop flooding developing country markets with subsidized American “assistance,” but other countries—most notably New Zealand but several others too—have proven that agricultural industry can thrive without substantial government support. Yet the Farm Bill ignores all of this and will almost certainly do so again in the coming months—with large, bipartisan majorities.

Chart(s) of the Week

The Links

My globalization project video (ICYMI)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.