Dear Capitolisters,

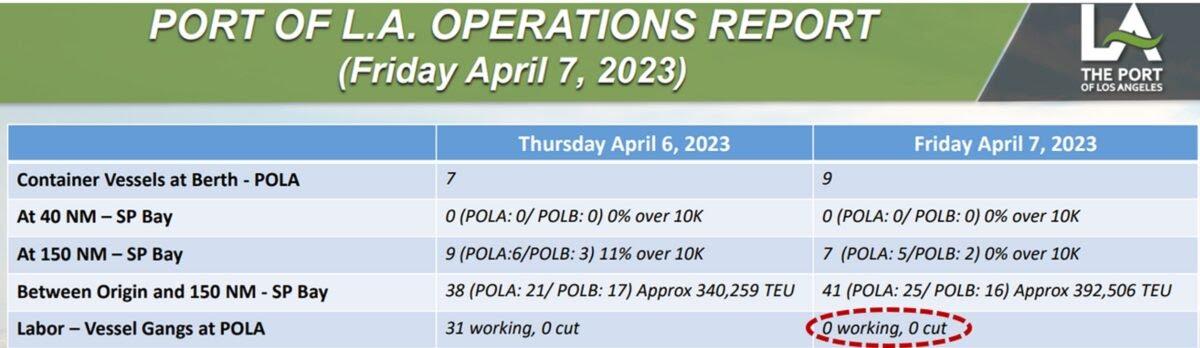

It seems like eons ago that I first wrote about some of the long-term, systemic problems at U.S. ports, and—spoiler alert—nothing much has changed. In fact, the long-simmering, semi-decennial contract talks between the International Longshore & Warehouse Union (ILWU) and West Coast port operators has, as I warned last year, officially entered a new phase of bad, with recent months’ work slowdowns turning into a full-on work stoppage right before Easter:

Other recent “work actions”—a euphemism for “not striking but not working in good faith either”—have also occurred, and with increasing regularity. The Journal of Commerce, for example, reported this week that ILWU dockworkers are now targeting the small handful of Los Angeles/Long Beach port terminals that are semiautomated, “red-tagging” cargo-handling equipment there (which deems it unsafe and forces an inspection) and thus further bogging things down. This, as the industry mag FreightWaves humorously explained last week, is par for the course and signals more strife in the weeks ahead: “Labor action at West Coast ports does not have a history of being explicitly confirmed; rather, it takes the form of passive-aggressive behavior that escalates with increasingly implausible deniability.”

As we’ve discussed repeatedly, labor disputes at U.S. ports occur somewhat regularly (basically every five years or so when the current contract is up), especially out West, and have recently centered on the issue of automation: Port operators and ocean carriers want to use robots, autonomous vehicles, drones, and other cool tech to boost container processing efficiency (“throughput”), while port unions strongly oppose this “job-killing” modernization. And, because the ILWU represents basically all dockworkers on the entire U.S. West Coast (22,000 of them at last count), because those ports are so critical to U.S. trade (especially imports from and exports to Asia), and because both labor law and California politics heavily favor the union, the ILWU been extremely successful in blocking technology that’s widely used around the world (even in places like Europe with strong labor unions):

In principle, West Coast dockworkers agreed to automation in contract negotiations in 2008 and in 2014. In practice, union leaders have resisted cargo-handlers’ efforts to automate. So far, just two of the 13 container terminals at the neighboring Los Angeles and Long Beach ports have been fully or partially automated. Two other facilities have started to introduce automation, or say they plan to.

The ILWU can cheer these “victories,” but the rest of us shouldn’t. Most obviously, research consistently shows that work slowdowns and stoppages act as a self-imposed blockade on imports and exports from the ports involved, hurting anyone—workers, companies, farmers, transporters, etc.—linked to those transactions and the U.S. economy more broadly. Thus, for example, the Congressional Budget Office in 2006 calculated that just the direct costs of an unexpected 7-day strike at Los Angeles/Long Beach would run between $65 million and $150 million per day. A 2008 paper, meanwhile, found that the 2002 West Coast port strike, which resulted in a 10-day lockout, “cost the U.S. economy billions of dollars,” created a 100-day backlog of ships waiting offshore, and depressed the stock prices of affected U.S. companies by approximately 8 percent on average. And a 2018 study found that just the work slowdowns in 2014-15, which the ILWU (of course) denied, significantly dented port efficiency for several months and thus generated more than $7 billion in direct economic losses and another $3-5 billion in indirect ones. (All values are in current dollars, so the losses would be much bigger if I weren’t lazy and did the inflation adjustment for you.)

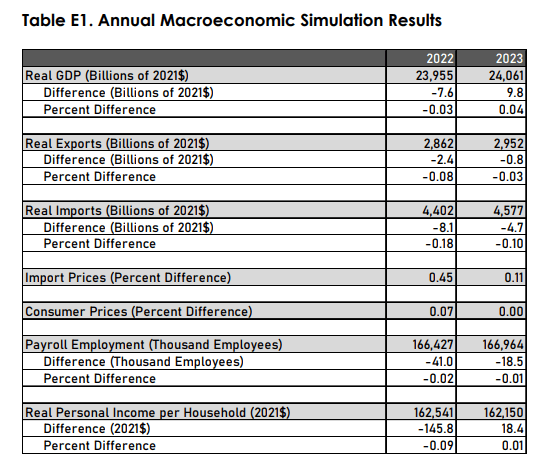

Most recently, a 2022 study commissioned by the National Association of Manufacturers found that a 15-day port disruption “would cost the U.S. economy nearly half a billion dollars a day—for a total of $7.5 billion—and destroy 41,000 jobs, including more than 6,100 in manufacturing.” It’d also represent, they estimate, a tax of “$146 per household” in 2022.

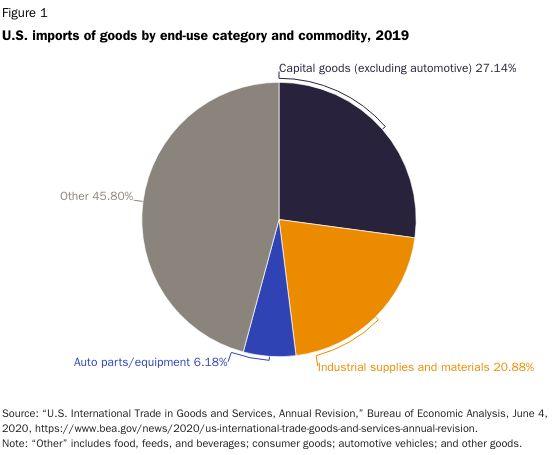

The report’s rundown (Table 1) of the goods routed through Los Angeles/Long Beach over the last few years shows the wide variety of industries that rely on the port—it’s basically every type of manufactured good and farm product you can think of, with perishable food items particularly hard hit because of spoilage (which limits rerouting them to other ports). U.S. manufacturers also suffer—not only because of diminished exports, but also because about half of all imports into the United States are inputs—raw materials, components, equipment, etc.—into American-made stuff.

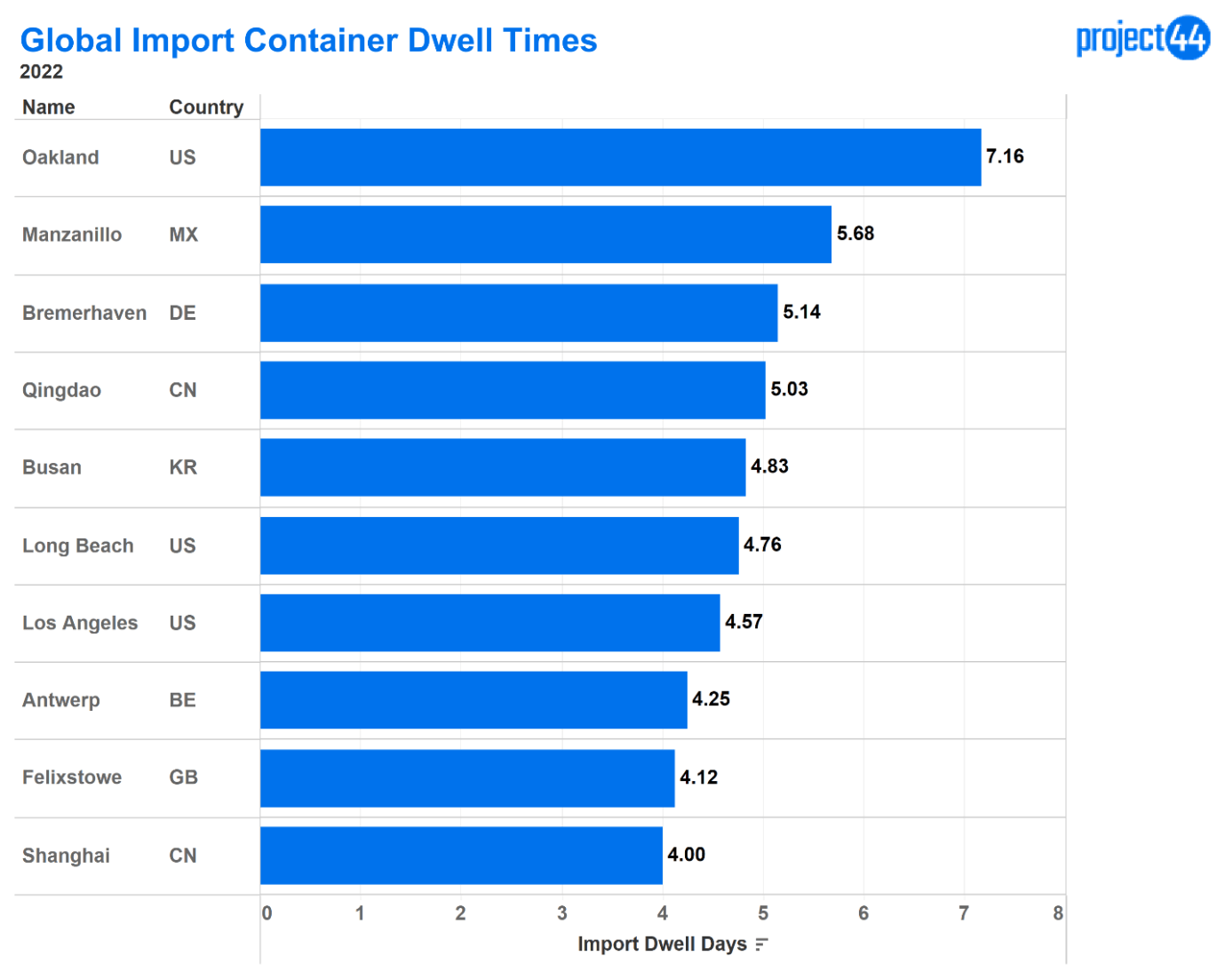

Second, the failure of U.S. ports on both coasts to improve their efficiency—the LA/LB complex ranks “dead last” by the World Bank, “trailing Luanda, Angola, and the Port of Ngqura, South Africa”—imposes broader economic harms. For example, a recent survey of transportation officials found that, while short-term congestion subsided, U.S. ports remain vulnerable to another economic shock (ship queues, container backlogs, etc.) because they haven’t adopted “an arsenal of short-term measures to address cargo surges” or expanded “their assets for the long term.” American port inefficiency also acts as an invisible tariff on all goods transiting these ports and thus will inhibit trendy U.S. “reshoring” and “friend-shoring” efforts because multinational manufacturers, even ones based here, will still need quick, easy access to global markets—access that U.S. ports can’t provide but competitors’ ports can:

Less port activity also means less work for everyone else in the supply chain. That’s why, for example, California’s port truckers strongly support automation (and “rail against dockworkers and city politicians” who block it).

Port delays and congestion even raise geopolitical concerns. For example, Chinese port efficiency is a big reason why multinational manufacturers locate there—and why it’ll be difficult for them to leave, no matter how much the U.S. government wants them to. The United States could improve its relative attractiveness by embracing port automation, but it unfortunately remains a lever that the ILWU and like-minded folks won’t let us pull:

The companies that transport and handle the cargo say the automation is one solution to the congestion at ports, particularly the Los Angeles and Long Beach sites at the heart of America’s supply chain woes. The spare use of robotics at U.S. ports leaves them uncompetitive with big gateways in China and Europe that are packed with automation, they say.

Jeremy Nixon, chief executive of Singapore-based container line Ocean Network Express, told the TPM22 Conference produced by The Journal of Commerce in Long Beach earlier this year that European and Asian ports can clear backlogs quickly because they have automated cargo-handling equipment that operates around the clock. “Here, we just don’t have that resilience,” he said.

The Chinese, on the other hand, have no such reservations:

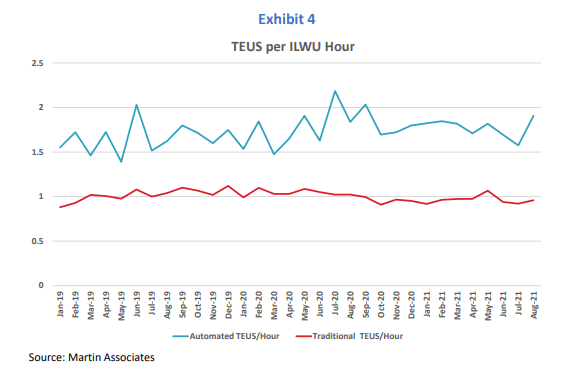

Finally, the ILWU’s efforts might even harm many West Coast port workers. For starters, the automation that the union so vehemently opposes (and now sabotages?) could increase—as automation often does—longshoreman employment and wages at the ports. That’s the conclusion of a recent Pacific Maritime Association study of two partially automated L.A. ports:

Among the key findings being highlighted by the PMA is that TEU throughput is 44 percent higher per acre at the San Pedro Bay’s automated terminals compared to the terminals with conventional operations. They highlight that the automated machinery can stack containers higher, closer together, and more efficiently for transfer to trucks or trains. At times, the two automated terminals have processed containers up to twice as fast as the non-automated operations.

“Critically, the study found that automation has not reduced job opportunities for dockworkers, as many workers have traditionally feared,” they write in the summary of findings. “The gains in output in Los Angeles and Long Beach mean that contrary to fears of job losses, automation has increased, not reduced, ILWU jobs and work opportunities, including training and upskilling.”

They cite data that shows between 2015, the last year before the transition to automated operations, and 2021, paid ILWU hours at the two automated terminals in the San Pedro ports rose 31.5 percent, more than twice the 13.9 percent growth rate at the non-automated terminals. In addition, the data shows that the registered ILWU workforce in Los Angeles and Long Beach grew 11.2 percent, compared to 8.4 percent for the other 27 West Coast ports, during the same timeframe.

Anecdotal evidence supports these conclusions, though the types of work could (and probably would) change.

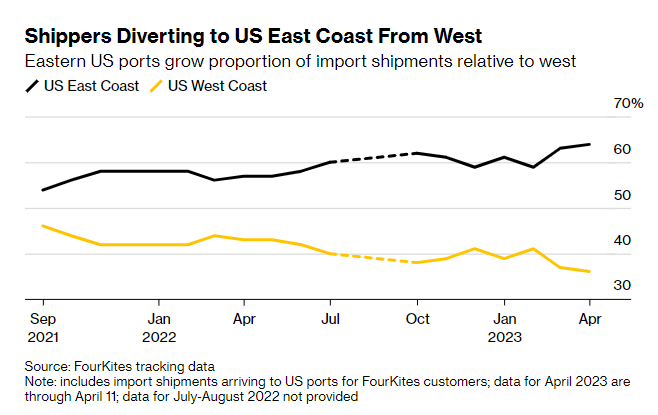

Just as importantly, a failure to improve West Coast port efficiency could push more cargo to other U.S. ports—meaning fewer jobs out West. Over the last year, in fact, concerns about labor strife and a general lack of efficiency have, along with other factors (e.g. facilities/waterway upgrades and U.S. economic growth in the Sun Belt), caused many U.S. companies to avoid West Coast ports and instead use ones on the Gulf of Mexico (especially Houston) and the East Coast:

One new study compared 2019 and 2023 cargo flows and concluded that around 1 million 20-foot equivalent (TEU) import containers per year have shifted away from U.S. West Coast ports to Gulf/East Coast ports, representing a 10.1% loss in volume for the former:

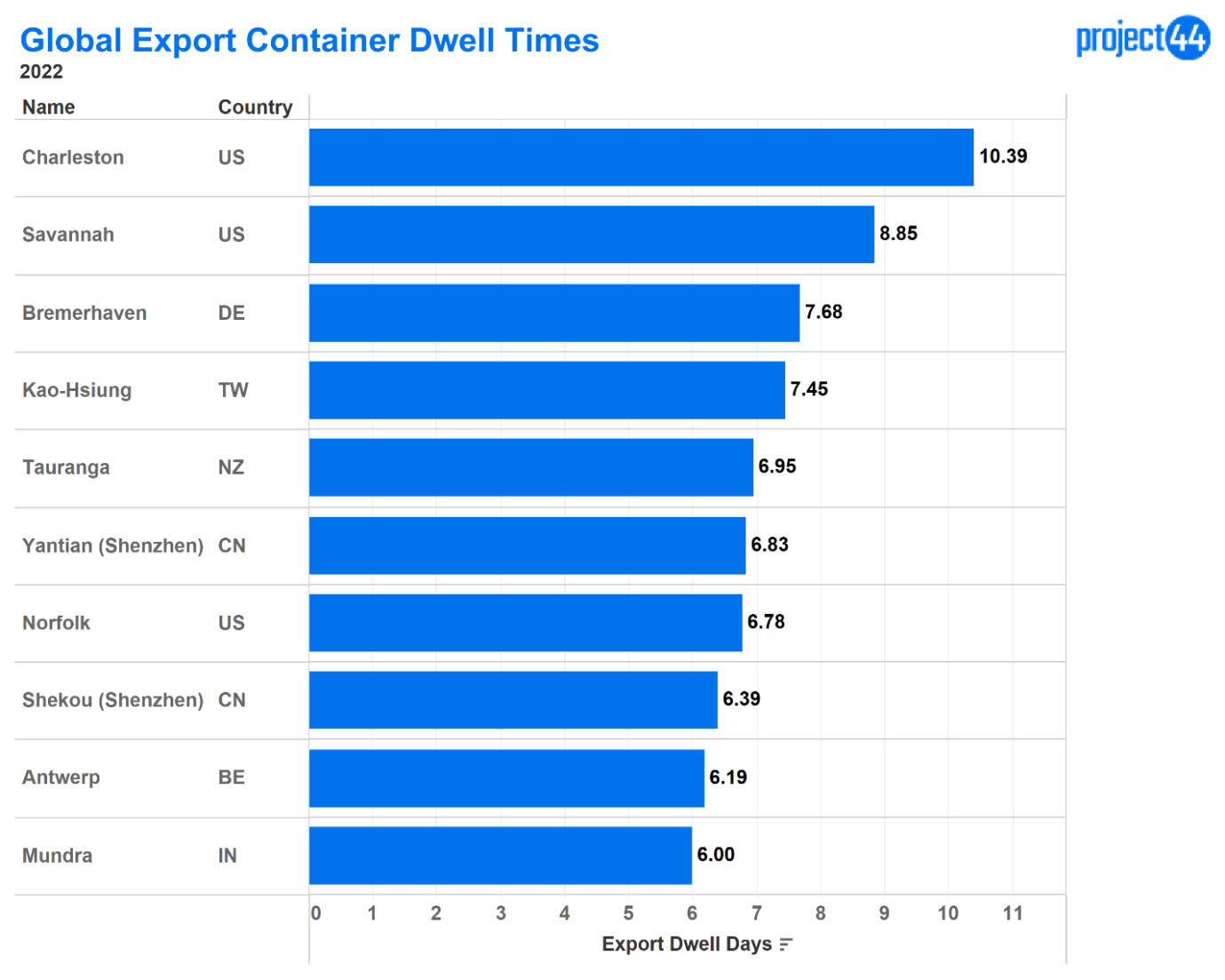

This month’s “work action” nonsense has generated new and growing uncertainty in this regard, “just as importers are making decisions on how to route goods into the country for the peak shipping season, which begins in a couple of months, when retailers stock up for the fall and the holiday sales period.” That means even more cargo diverted away from the West Coast—where containers, even with the cooling economy, still sit around for significantly longer periods than at other ports—and less work for everyone involved:

The local downward trend [in port traffic] is worrisome not just to officials at the twin ports but also for 175,000 Southern California workers — employed at the harbors themselves as well as in related businesses — moving freight valued at $469 billion a year, port data show. At stake are jobs all along the supply chain, including truckers, warehouse workers and people employed by logistics specialists.

Even if the current labor talks are eventually resolved without a major disruption, the longer this drags on means, as the National Retail Federation recently warned in a White House letter, “some portion of the freight will never return to the West Coast ports.” In fact, one recent estimate suggests that the 10 percent decline in West Coast cargo will endure, thanks to existing “logistics bottlenecks, regulatory headwinds and labor uncertainty.” Should the ILWU win future limitations on port automation, thus promising diminished efficiency for years to come, the shift could become even more pronounced—and permanent.

That result might work out well for ILWU officials, whose jobs remain and clout (political or economic) grows regardless of whether ports stay antiquated. And it might be fine (lucrative, even) for many rank-and-file port union members who keep their jobs even as West Coast volumes wane. But since the ports, even in a relatively diminished state, will remain important to U.S. trade (and thus U.S. farmers and businesses), the price of ILWU “victories” on port automation and other efficiency improvements (e.g., on schedules) could be high—for the U.S. economy overall and for millions of other American workers, including some employed at the ports today (or hoping to be so employed in the future) or standing elsewhere in political “solidarity” with their union brethren on the docks. (For the 94 percent—and climbing—share of the U.S. private sector workforce that isn’t unionized, of course, it’s all downside.)

Given the real and potential harms that port closures raise for the U.S. economy and national security, past presidents—George W. Bush in 2002 and Richard Nixon in 1971—have invoked emergency provisions of the Taft-Hartley Act to force West Coast ports to resume their operations. That might sound crazy, but consider that economists routinely group port strikes and lockouts with other natural and man-made “disasters” that disrupt global maritime operations:

In a somewhat hilarious coincidence, in fact, the Wall Street Journal reported mere weeks before the ILWU’s Easter no-show that Pentagon officials today worry that Chinese-made cranes operating at U.S. ports might allow some nefarious actor to—I kid you not—“disrupt the flow of goods” in and out of the country.

Something tells me that President Biden isn’t as concerned about a domestic player doing the same.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.