Dear Capitolanivimab,

Happy Tuesday-before-Thanksgiving! At this point, I hope you’ve dominated your Practice Turkey and are now working on the (unfortunately smaller) Thursday feast, as everyone knows that a truly great Thanksgiving meal takes several days of preparation. In that regard, you’ll find in the links section below my mom’s world-famous apple/cornbread/sausage stuffing recipe, which should be started today and is easily the best thing you’ll ever ingest ever. So if you haven’t yet started on your own (inferior) stuffing, I’d recommend you stop reading and head to the grocery store NOW.

OK, good.Now that you’re back, let’s move on to more serious things.

I planned this week to write about a labor market silver lining to COVID’s dark clouds, but Jonah’s column last Friday redirected things because I think what he wrote about Trump and the 2020 election is right and important—even now that President Trump has kinda-sorta-maybe admitted that he won’t be president in 2021. So I want to spend a little time today providing some additional reasons for concern regarding the political spectacle we’re still seeing play out on the internet, various media, and in courts across the country.

First, let’s just reiterate that there is still no legitimate evidence of a massive conspiracy, whether at the state, national, or global level, to rig the 2020 U.S. presidential election in Joe Biden’s favor. Last week Jonah andThe Dispatch Fact Check crew, as well as my Cato colleague (and cybersecurity expert) Julian Sanchez, ably dismantled these claims, which—almost unbelievably! –only got nuttier thereafter. On Friday and Saturday, respectively, two different federal judges—a Trump appointee in Georgia and an Obama appointee (but Republican Federalist Society member) in Pennsylvania—quickly dismissed other legal challenges to the votes in these states, finding them to be essentially groundless (if not worse).

Still, as of my writing this, the president of the United States, several administration officials, the Trump campaign, his (ever-changing) personal legal team, and several state and national leaders of the Republican Party continue to allege in public that a massive, historic fraud has been committed against the American People. Yes, Trump issued a tweet that seemed to acknowledge the reality of his loss, and Sidney Powell is now gazing at the undercarriage of the MAGA Express, but the legal challenges, presidential tweets and retweets (of Randy Quaid, no less), and Tucker Carlson monologues are still going, as is the Republican Party acquiescence, save a few commendable outliers.

As Jonah noted, this is no joke, despite the obvious absurdity of the allegations and sitcom-esque behavior of its protagonists. And the damage they have inflicted—and may still be inflicting—upon the public trust could be substantial, with harms that extend far beyond just our electoral system.

Now, I fully admit that I’m not yet sure just how much damage they’ve done at this stage—if the “strikeforce” clown car continues to backfire and the president continues to retreat, maybe most Americans currently caught up in the moment will wake up or calm down (or both) and we’ll all be able to look back at 2020 and laugh with relief (and a stiff drink). Maybe.

Nevertheless, serious concern is warranted, especially given the president’s unique, Svengali-esque ability to influence the beliefs and actions of millions of Americans—and the cadre of politicians and media personalities willing to reinforce those beliefs for donations and clicks.

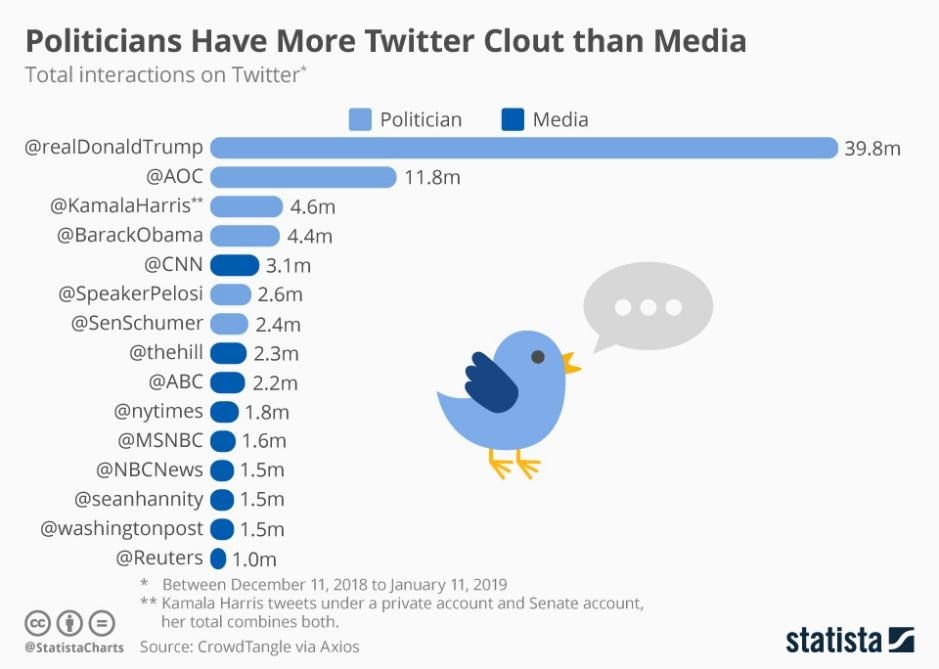

Indeed, there is no politician—and maybe no human—on the planet today who can speak to more people without an intermediary:

Because of this reach, its network of amplifiers, and Trump’s own promotional talents, poll after poll over the last four years has shown how Trump, fueled by the nation’s increasing political polarization, can alter Americans’ views of the economy, the pandemic, and (as I showed last week regarding trade) specific policy or cultural issues. (See also this new academic research on how Trump’s election in 2016 altered norms around immigration.) Perhaps the most telling example of this phenomenon came this year, as Republicans continued to overwhelmingly support Trump’s economic performance during the middle of the deep COVID recession, even when they themselves had fallen on hard times: “[n]early three in 10 Republicans who lost jobs say they are better off economically than they were a year ago, a sentiment that is shared by barely one in 10 Democrats who have kept their jobs throughout the crisis.”

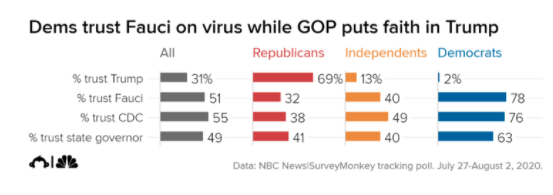

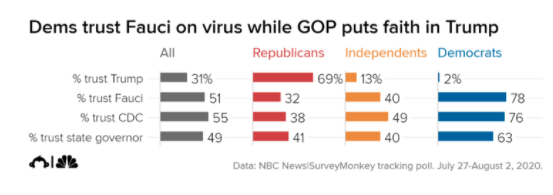

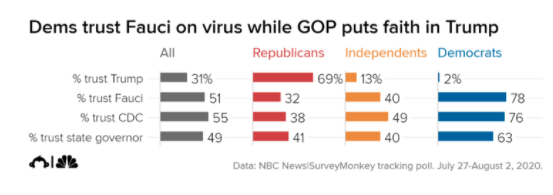

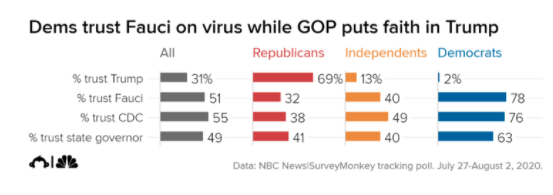

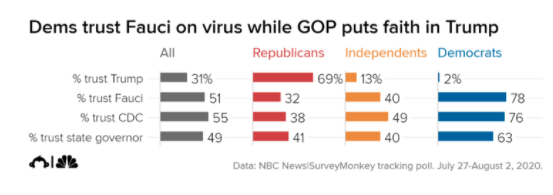

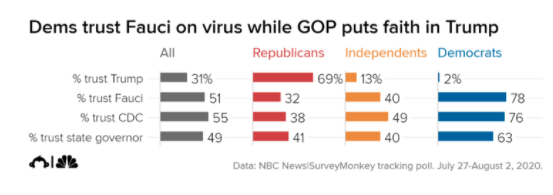

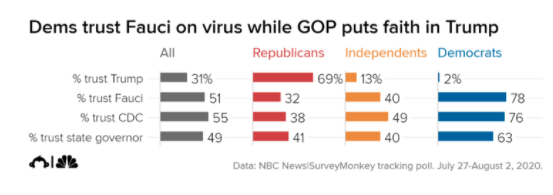

At the same time, these dynamics, along with media and partisan overreach (to put it mildly), have created a bunker mentality among many Republicans, such that they trust Trump—and Trump alone—over anyone else, even friendly media outlets:

Given this informational dynamic and pre-existing GOP trust cocoon, it’s utterly unsurprising to see that Trump’s two-plus-week attack on the integrity of the U.S. election process has caused Republicans’ trust in the system to plummet:

Yes, some of this is just partisanship: Note in these polls how Democrats’ views of the system—and even past elections!—improved after Biden’s victory. However, the magnitude of the GOP swings, as well as certain responses (see charts below) show that something bigger-than-the-usual-partisanship is clearly going on:

Other polls and anecdotal evidence back up these findings. Reuters, for example, spoke to a random collection of 50 Trump voters over the weekend and found them uniformly supportive of Team Trump’s take on the election:

“If President Trump comes out and says: ‘Guys, I have irrefutable proof of fraud, the courts won’t listen, and I’m now calling on Americans to take up arms,’ we would go,” said Fryar, wearing a button-down shirt, pressed slacks and a paisley tie during a recent interview at his office.

The unshakable trust in Trump in this town of about 1,400 residents reflects a national phenomenon among many Republicans, despite the absence of evidence in a barrage of post-election lawsuits by the president and his allies.

Be sure to read the whole thing to get the full flavor of the responses. They do not appear to be cherry-picked, either. Reuters also cited additional polling from mid-November showing that at least half of Republicans think Trump “’rightfully won’ the election but had it stolen from him in systemic fraud favoring Biden,” while less than 30 percent think Biden “rightfully won.” Other polls show the same: high Republican trust in Trump (and his conspiracies) combined with low trust in the electoral process and their fellow Americans running it—even ones in the Republican party!

And just this morning he took to Twitter to reinforce their beliefs:

So why does this matter? Should we really even care about the erosion—if not outright destruction—of millions of Americans’ trust in both the U.S. system of governance and their fellow citizens? Why not just relegate these people to a rump Conspiratorial Loon Party status and move on with our lives?

Well, beyond the mere depressingness of the situation, the deterioration of our fellow Americans’ trust can affect us too, and the nation more broadly, in all sorts of ways—ways that conservatives and libertarians might especially dislike. Most notably, a wide body of academic literature shows that interpersonal trust levels are connected to trust in public institutions and a key determinant of various positive economic outcomes. For starters, there is a very strong correlation between the extent to which individuals trust each other and personal income (Gross domestic product per capita):

As can be seen in the chart above, the more a nation’s citizens trust one another (moving up the Y axis), the richer that country tends to be (moving right on the X axis). As noted at the above link, moreover, trust also has been found to generate more economic growth, more entrepreneurialism, and less income inequality. Other studies support the aforementioned conclusions and also have found significant connections between higher trust levels and improved financial market performance, investment, innovation, productivity and labor relations. On the other hand, countries with lower trust levels (trust in others, trust in firms, or trust in political institutions) tend to have higher levels of regulation and bureaucracy.

All of this makes perfect sense, fancy chart notwithstanding. Every day, individuals (who are often total strangers) undertake millions of spontaneous, voluntary transactions. To the extent that these people trust neither one another nor the legal system that supposedly regulates and protects their transactions (e.g., from fraud), they will either (1) have fewer interactions; and/or (2) invite greater state scrutiny and involvement. By contrast, “when people expect to live in a civic-spirited community, they expect low levels of regulation and corruption, and so become civic. Their beliefs have a self-justifying property, as their choices lead to civic-mindedness, low regulation, and high levels of entrepreneurial activity.”

Trust doesn’t just affect economic stuff, either: “[C]ountries where people are more likely to report trusting others, are also countries where there is less violence and more political stability and accountability.” More trusting countries also tend to have higher quality legal systems (though there is a “chicken-egg” question of causation here).

In short, trust—in each other and in our institutions generally—really matters, so its intentional deterioration among millions of our fellow Americans should be cause for serious concern. That’s especially the case today, as trust levels in the United States have been declining in recent years, particularly among Americans with less education (e.g., the Trump diehard base):

Trust in the federal government has similarly declined over this period, while trust in state and local governments has been surprisingly positive.

(Until recently, at least.)

Now, I don’t mean for a second to imply that Trump’s behavior has singlehandedly destroyed American trust (and thus the nation’s future economic and social prospects). As shown above, national trust levels have been declining for years and Democrats have their own (albeit smaller) issues with accepting election outcomes. Nevertheless, there is simply no denying that the president’s current, weekslong attacks on the legitimacy of our electoral system, on the actions of thousands of state/local officials and volunteer poll workers, and on millions of American votes may—given his position, influence, and persistence—be fundamentally different and more damaging than anything we’ve seen before. This isn’t Hillary Clinton in the New York Times (years after the election, by the way). It’s a sitting president with unlimited reach, unprecedented influence, and an entire team (formally and informally) behind him—a president who not only affects the behavior and beliefs of his diehard followers, but also his enemies—and often to similar, albeit polarized, conspiratorial effect.

This last point bears emphasis: President Trump’s actions risk radicalizing not only his millions of diehard fans but also millions of others who become convinced that a sitting president—or, at least, one more competent—actually can steal an election. As political scientists Henry Farrell and Bruce Schneier put it recently:

The real fear is that this will lead to a spiral of distrust and destruction. Republicans—who are increasingly committed to the notion that the Democrats are committing pervasive fraud—will do everything that they can to win power and to cling to power when they can get it. Democrats—seeing what Republicans are doing—will try to entrench themselves in turn. They suspect that if the Republicans really win power, they will not ever give it back.

That’s not good. Not good at all. And, as already noted, those effects would extend far beyond whose name is on the Speaker’s gavel or Oval Office door.

No amount of “payback” or “lib-owning” can be worth that, can it?

Chart of the Week

(source)

The Links

Steel and aluminum tariffs: still bad (And the trade economists were right)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.