Dear Capitolizers,

Well, that was quite the year we had last week. Sheesh. Anyway, as of this writing, the future composition of the U.S. executive and legislative branches is still a little unclear, but it’s increasingly looking like 2021 will feature a President Biden, a Speaker Pelosi, a Majority Leader McConnell, and little in the way of a governing mandate for any of them. (Count me among those who do not expect a Blue Wave in Georgia’s two upcoming Senate runoffs once Trump’s name is off the ticket.) This prospect has elicited the usual laments about divided government, federal policy-making, and the nation’s economic prospects. This pessimism, I think, is mostly wrong. In fact, there is substantial evidence that political gridlock can actually be pretty good for the economy and especially good for fans of limited government and fiscal restraint.

So today we’ll look at the (mostly) good and (potential) bad of a divided federal government, starting with the latter. Grab your leftover nachos and let’s dig in.

The Bad

It’d be wrong, I think, to say that all political gridlock is all good (hence, the title of this week’s column). For starters, we can all probably think of situations in the past where unified government produced some pretty good federal policy (immigration in 1965 and taxes in 2017 immediately come to my mind).

Furthermore, I see at least two ways in which a divided federal government can create legitimate policy or economic concerns. First, as both the Obama and Trump eras proved, U.S. presidents have increasingly chosen a “pen and phone” approach to policy-making—far beyond merely modifying previous administration’s regulations or executive orders—when the legislative branch won’t do what they want, and the courts have so far provided only a limited (and often delayed) check on such unilateralism.

There’s every reason to think a President Biden, under pressure to show “results” without a willing Congress to help him, would follow a similar (albeit maybe more limited) approach in the areas—like trade and national security—where the president’s powers are least checked. I didn’t like this stuff under Obama or Trump and won’t be cheering it under Biden, either.

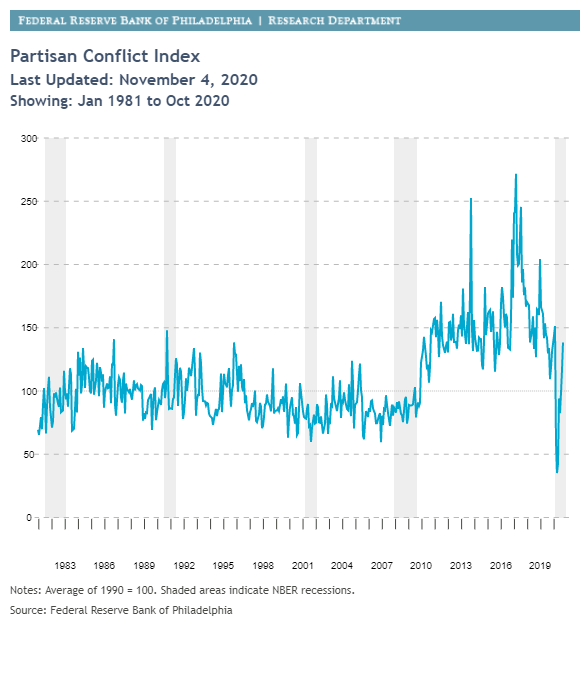

Second, some research shows that political discord increases economic uncertainty, which in turn can hurt the economy. For example, a recent study of business innovation activity in 43 different countries found that “political uncertainty” (as opposed to one certain party in charge) hurts innovation because domestic businesses hold off on investments and inventions—particularly risky ones—when their future financial return is unclear. This effect is particularly strong in election years, when the government’s future makeup is unclear. Similarly, Philadelphia Fed research finds that partisan conflict can “slow economic activity by delaying business investment and consumer spending,” and that this conflict has increased significantly in recent years:

(Do note the dramatic temporary reduction in partisan conflict earlier this year, when Congress passed a series of anti-pandemic economic and medical aid bills; even in deeply partisan times, a true national crisis can sometimes be enough to shake things loose for a bit.)

That said, a divided U.S. government doesn’t necessarily mean political conflict or uncertainty: Some historical analyses actually show that divided governments can function as well or better than unified ones, and a Biden presidency should be an improvement over the significant uncertainty and conflict that was unique to President Trump. Indeed, early reports are that Sen. Mitch McConnell may be trying to dial back the partisan conflict and compromise with Biden, at least on things like Cabinet picks and COVID-19 relief. It’s also likely that a President Biden won’t be as erratic as Trump, especially on immigration and trade policy (where Trump’s actions have been repeatedly shown to have harmed growth and investment), and I seriously doubt he’ll craft policy by tweet. So, while there’s certainly a potential for the Philly Fed’s Partisan Conflict Index to stay elevated, it’s definitely not assured.

The Good

Beyond that (limited) optimism, there are two good reasons to think that divided government and political gridlock are not only not an economic or policy problem but actually a pretty good thing in their own right.

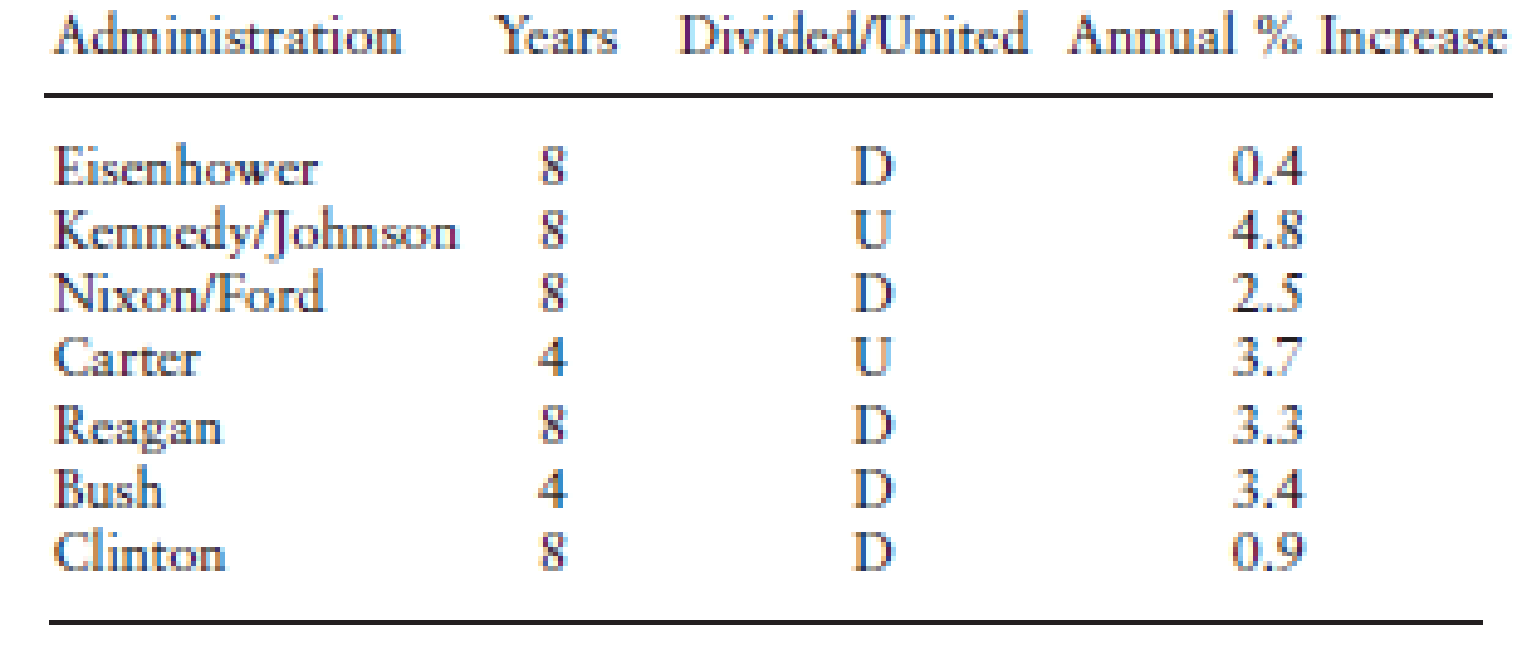

First, as longtime Cato Institute Chairman and former Reagan administration economist Bill Niskanen famously argued, political gridlock often generates policies welcomed by supporters of limited government and fiscal restraint, while unified government often produces the opposite. The most obvious example is on spending: For example, Niskanen in 2003 examined federal spending from the 1950s to 2000 and found that “[t]he only two long periods of fiscal restraint were the Eisenhower administration and the Clinton administration, during both of which the opposition party controlled Congress”:

The trend continued in subsequent years: When the GOP was in charge from 2003 to 2007 and then 2017 to 2018, spending increased at an average annual rate of 7 percent and 4 percent, respectively; when Democrats were in control during Obama’s first two years, it climbed 16 percent. On the other hand, when government was divided during the last six years of the Obama era, spending climbed at an annual average of just 1.9 percent.

As you may recall, those years also produced one of the few recent victories for real fiscal restraint—the 2012 and 2013 “sequester” spending cuts associated with the 2011 Budget Control Act—and it was a classic case of divided government compromise. In particular, House Republicans granted President Obama’s request to increase the debt ceiling by $900 billion in exchange for the same amount of federal spending cuts over the next decade. The result: the first time government spending fell two years in a row since the 1950s.

Beyond spending, Niskanen found that divided government often produced better governance. Pointing to the Reagan tax laws of 1981 and 1986, as well as Clinton-era reforms of agriculture, telecommunications, and welfare in 1996, he concluded that “[t]he probability that a major reform will last is usually higher with a divided government, because the necessity of bipartisan support is more likely to protect the reform against a subsequent change in the majority party.” Jonah added other data points last week:

It’s worth recalling that 1988 was a good time for grown-up governing. Say what you will about Poppa Bush’s betrayal of his “no new taxes” pledge, it was done in the spirit of responsible government. George H.W. Bush also handled the reunification of Germany and the savings-and-loan crisis with quiet, grown-up professionalism and statesmanship.

Similarly, gridlock can reduce rent-seeking among organized special interest groups. As University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee professor Marcus Etheridge explained in a 2011 paper, under a divided U.S. government, (1) well-organized/well-funded political actors (e.g., the steel industry) are less certain that the rents they seek will be profitable to them because legislative outcomes are less certain; (2) the lobbying costs of acquiring these rents are higher; and (3) the participation of “unorganized citizens” becomes more significant and effective. By contrast, “an institutional arrangement that is not frustrating and protracted will be dominated by interests with superior organizations and political skills.” Indeed, lobbying dollars reportedly fell after the aforementioned sequestration, and tax lobbyists are already paring back their expectations for major tax-related work if the GOP does indeed control the Senate (insert world’s smallest violin).

Finally, there’s foreign policy, where Niskanen notes that “the prospect of a major war is usually higher with a united government,” citing both Afghanistan/Iraq (Republicans) and each of the four major American wars in the 20th century (Democrats). Unilateral foreign policy adventurism has undoubtedly (and unfortunately) increased since then, regardless of the government’s makeup, but a GOP Congress did still occasionally push back on Obama’s unilateralism (e.g., in Libya).

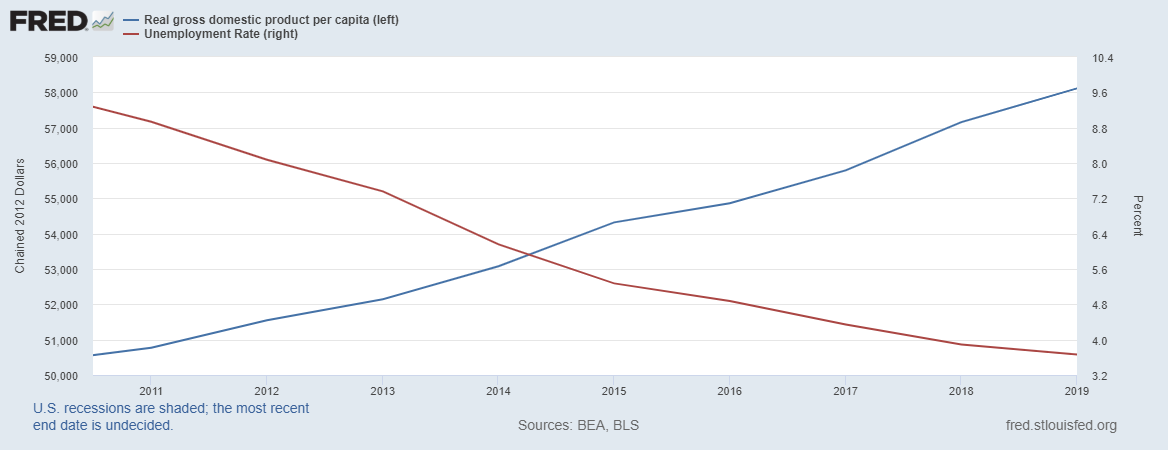

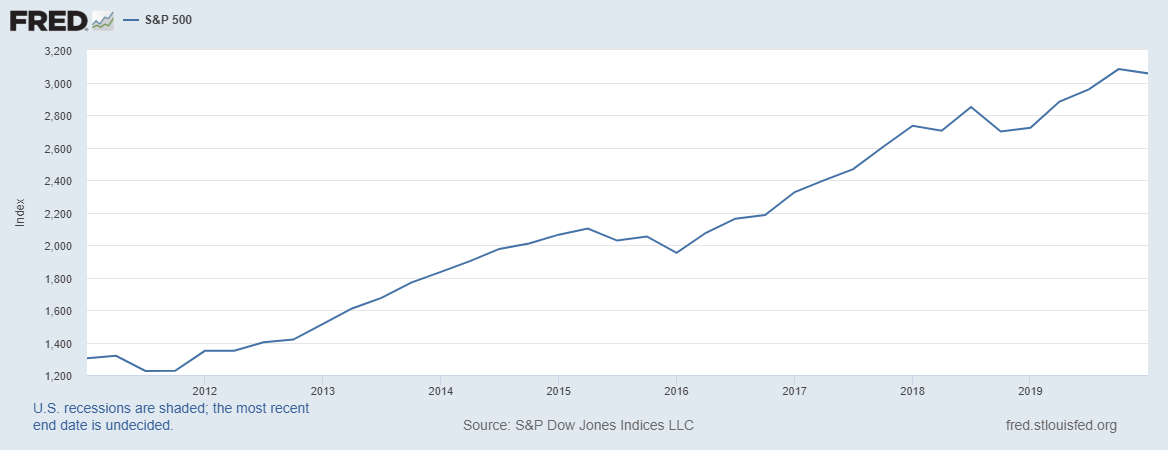

Second, and perhaps for the aforementioned reasons, the economy performs as well, if not a little better, under a divided government than under a unified one (even considering the potential economic uncertainty mentioned above). Examining various economic indicators between 1970 and 2010, Kevin Hassett (formerly of AEI and the President Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers) found that:

From 1970, median GDP has grown 3.3 percent in years of divided government (1970-76, 1981-92, 1995-2002, 2007- 08), compared with 3 percent when government was unified (1977-80, 1993-94, 2003-06, 2009-10) … Since 1970, median unemployment has been 6.1 percent under one-party rule, 5.7 percent when both parties have some control….[and] the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index has increased at a median rate of 13.5 percent per year in divided times and 9 percent per year under one-party rule.

More recent history is a bit muddled due to the Great Recession and COVID-19, but the charts below again show little economic harm from divided government during Obama’s last six years or in 2019 under Trump:

In fact, a 2016 analysis found that “GDP grew faster and the unemployment rate fell more quickly in the 18 months after the sequester went into effect than it did in the 18 months that preceded it.” Correlation isn’t causation, of course, but this remains pretty good evidence against the all-too-common claim that divided government and fiscal restraint will harm the economy.

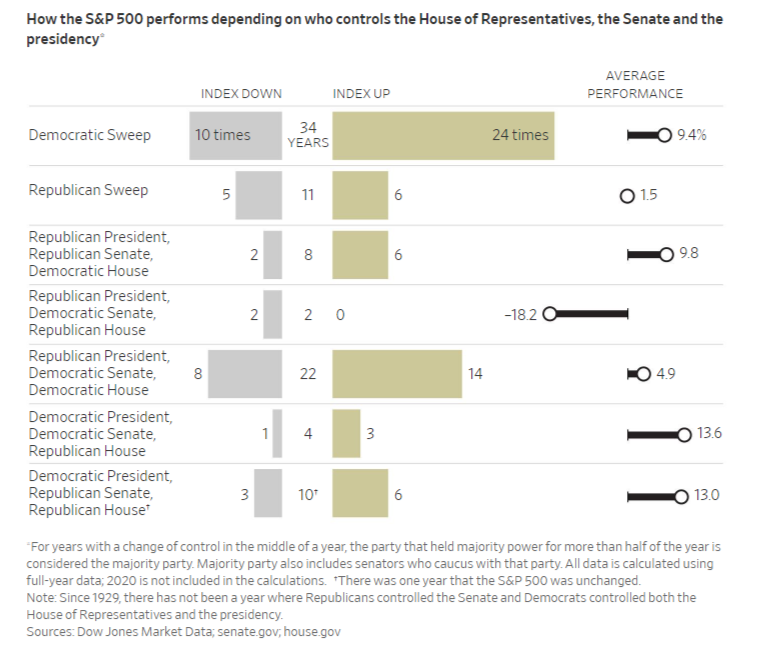

Markets appear to agree (at least so far): In the days following the election, the Dow, S&P and NASDAQ have shot up several percentage points—even as the president rage-tweeted the returns and vowed to fight it out in court. Historically, a divided U.S. government has generated about the same stock market returns as a unified one, but the sample size is small and “every cycle is different.”

With respect to the current cycle, however, the market appears to like what it sees. A lot. Now, some of this bounce is undoubtedly due to reduced uncertainty regarding the election outcome (see the Chart of the Week below), but New York magazine’s Josh Barro gets at some other reasons, all of which support my first point above:

Trump leaving office should mean an easing of international trade tensions that have harmed manufacturers and other corporations that rely on trade with China. It should also mean less policy uncertainty—no need to watch the president’s Twitter feed for clues about whims that could change the fortunes of businesses. But continued Republican control in the Senate means there aren’t likely to be the significant increases in corporate or capital-gains taxes that Joe Biden hoped to implement. The Senate may also act as a check on Biden’s appointments: Needing to get confirmation from an opposition-controlled Senate, Biden is unlikely to pick a progressive favorite like Elizabeth Warren for Treasury Secretary and is more likely to renominate Jerome Powell to run the Federal Reserve. Investors who wanted Trump to go but wanted some of his policies to stay will have their cake and eat it, too.

Sounds pretty tasty to me. (And Barro is certainly not alone.)

Now on to Georgia …

Chart of the Week

Decision Desk HQ deserves a lot of credit for calling the election first on Friday, but the stock market’s fear gauge, the Cboe Volatility Index (VIX), seems to have called it even sooner.

Bonus Chart of the Week

This seems good. (Source)

The Links

Me on tariff history repeating itself, again

2020 ballot initiatives were a “pretty good day for liberty”

Photograph by Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.