Dear Capitolisters,

After a week-plus of intense political drama, House Republicans today ousted Wyoming’s Liz Cheney as GOP Conference chair, the third-ranking Republican in the House of Representatives. Unless something zany happens, she’ll soon be replaced by New York’s Elise Stefanik, a young and rabid supporter of ex-President (and apparent horse racing fan?) Donald Trump. Beyond the usual insider scoops and juicy (for political obsessives) quotes, the media have focused primarily on what these moves mean for the GOP in terms of fealty to Trump and the apparent tensions between pleasing him and winning elections, especially in the Trump-skeptical suburbs. (Sounds familiar.) More interesting, I think, is what the situation might say about the current state of Republican Party policy.

Little of it is good.

As you may have heard, several conservatives have lamented Stefanik’s rise to the top of the House GOP because she had one of the least conservative voting records in the caucus, neatly summarized here by Henry Olsen of the Ethics and Public Policy Center:

Her lifetime score from the conservative group Heritage Action is a mere 56 percent, compared with Cheney’s 91. She similarly lags behind Cheney in rankings compiled by the fiscally conservative Club for Growth and neo-libertarian Freedom Works. The group Americans for Tax Reform has criticized her in the past for not signing their famous pledge to reject raising taxes (she won her initial GOP primary 2014 despite this apostasy), a position she has not changed since. Stefanik’s 2019 endorsement of the Equality Act worries many religious conservatives, too.

As a result of this voting record, the fiscally conservative (and generally Trump-supportive) Club for Growth went so far as to publicly oppose Stefanik, arguing instead that “House Republicans should find a conservative to lead messaging and win back the House Majority.” Texas Rep. Chip Roy did the same in a “remarkable three-page broadside” issued yesterday to his colleagues. And the AP reports that other conservative Republicans, including the House Freedom Caucus, are “known to be uncomfortable with her.” (How brave of them.)

For these folks, Stefanik’s voting record is bad for the Republican Party because it doesn’t reflect the party’s conservative policy priorities or principles. Olsen, by contrast, wants us to believe that it’s a good thing, potentially signaling a Republican policy move from “conservative” fundamentalism (or whatever) toward “moderate” policy that can capture more liberal “Trump voters.”

Both views, however, seem not to recognize just how little policy—conservative, liberal, or some kind of “Trumpian” hybrid—matters in the Stefanik/Cheney saga. Indeed, as AEI’s Marc Thiessen shows, the Trump-supporting Stefanik actually voted with Trump much less often than Trump-critic Cheney:

Cheney voted with Trump 92.9 percent of the time, while Stefanik voted with Trump just 77.7 percent of the time. Indeed, Stefanik steadfastly opposed key elements of the Trump agenda. She voted against Trump’s singular legislative achievement—his 2017 tax reform bill—and against making his tax cuts permanent. She voted to block Trump from withdrawing from the Paris climate accords. She voted to condemn Trump for calling on the courts to invalidate the Affordable Care Act. She voted to overturn Trump’s emergency declaration at the southern border so he could fund the border wall, and then voted to override Trump’s veto of a bill that reversed his emergency declaration.

Installing Stefanik thus does not indicate the GOP’s rejection of “Reaganite” conservatism or its embrace of populist Trumponomics. Instead, as Thiessen put it, “This is not about ideology or public policy. It’s not even loyalty to Trumpism. It’s about loyalty to Trump.” Indeed.

Unfortunately, the GOP’s current (momentary?) elevation of Trump—and the culture war that he (still) leads—above policy and principles extends beyond the Cheney-Stefanik situation and even made-for-TV dramas like Dr. Seuss. Instead, GOP “policy” this year has repeatedly been reverse-engineered—pick targets and then craft policy to effect them—to advance various Trump and culture war priorities. As HotAir’s pseudonymous Allahpundit first noted when the Georgia voting law kerfuffle first broke, Republican “economic policy is now seen mainly as a cudgel against cultural antagonists”—and often in ways diametrically opposed to the conservative positions Republicans claim to hold.

The most obvious example of this type of “policy”making is the GOP’s current crusade against “Big Tech,” proposing measures—like Section 230 repeal or treating social media companies like public utilities—that would enlarge government, stifle constitutionally protected speech, slow economic growth and dynamism, and likely empower the very Big Corporations that Republicans want to weaken. Last week, the party’s Big Tech priorities reached their absurdist peak (so far!) when the Florida GOP passed legislation, which Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis intends to sign, that fines social media companies that “knowingly deplatform” political candidates (like a certain ex-president) but exempts “theme parks” (like, oh I don’t know, Florida-based Disney!) from the regulation. This one checks all the ridiculous boxes—including being blatantly unconstitutional and hilariously avoidable (bring on “Zucker Land”!)—but it’s hardly alone or limited to the always-entertaining state of Florida.

For example, congressional Republicans in April proposed revoking the antitrust exemption for Major League Baseball and nixing Delta’s jet fuel tax break, both in response to the companies’ actions on the Georgia voting law. (The MLB move even made it into real legislation.) A few weeks before that, Sen. Marco Rubio penned an op-ed decrying adversarial corporate-labor relations yet openly rooting for unionization at its Alabama facility. (Oops.) And as reported here last week, likely Ohio Senate candidate J.D. Vance even went so far as to urge Republicans to raise the taxes of (and do “whatever else is necessary” to) the businesses that opposed Republican-led efforts to change state voting laws, while cutting the taxes of “companies (big and small) paying good wages to American workers, investing in their communities, and making it easier for American families.” Carrots and sticks, I guess.

All of this behavior leaves us with one of two conclusions about the current GOP, neither of them flattering: Either Republicans are keeping their policy priors—tax cuts are still good, current U.S. union policies are bad, etc.—and just excepting certain corporate villains from the general rules, or they just never believed in those policies in the first place. Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, for his part, seems to have admitted the latter a few weeks ago in the Wall Street Journal (emphasis mine):

This is the point in the drama when Republicans usually shrug their shoulders, call these companies “job creators,” and start to cut their taxes. Not this time.

This time, we won’t look the other way on Coca-Cola’s $12 billion in back taxes owed. This time, when Major League Baseball lobbies to preserve its multibillion-dollar antitrust exception, we’ll say no thank you. This time, when Boeing asks for billions in corporate welfare, we’ll simply let the Export-Import Bank expire….

We cast votes, too. And we pay attention when CEOs come after our own just so they can look good for a few editorial pages and radical activists.

To them I say: When the time comes that you need help with a tax break or a regulatory change, I hope the Democrats take your calls, because we may not.

As economist John Cochrane noted at the time: “Cruz’ statement is unintentionally devastating. So what about last time? So there it is in front of us, in writing, from a major politician. Political support, and campaign cash bought $12 billion tax breaks, antitrust exemptions, and Ex-Im subsidies. From Republicans. So much for any public policy pretense.” Ouch.

Now, surely, some of these exemptions and subsidies do warrant reform (at least, from a conservative perspective); some Republicans are still trying to make good policy; and some of the aforementioned nonsense is just media fodder for ambitious politicians (there are a lot of 2024 hopefuls in the above items). But culture-war policymaking also has infected the righty wonkosphere too, which all too often appears to pick cultural enemies—Big Tech, “libertarians,” Wall Street, globalization, etc.—and then craft policy to accommodate the pre-existing aversion.

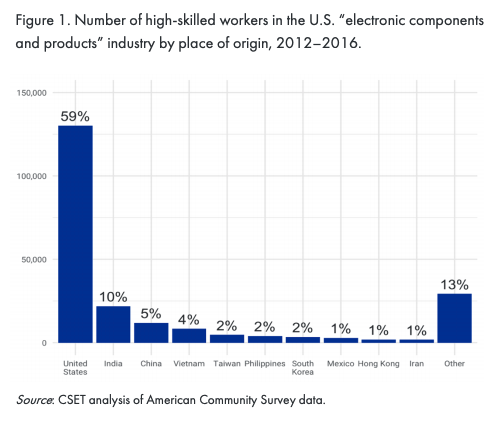

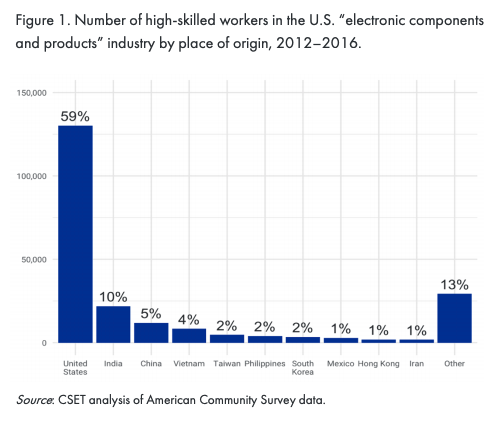

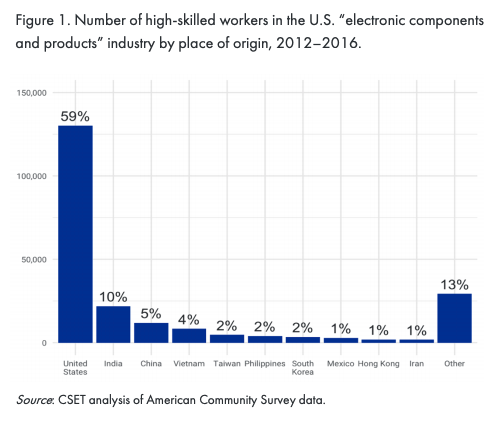

There’s perhaps no better example of this phenomenon than immigration and the resurgent view among many on the right that America needs a robust “industrial policy.” Both academic work and U.S. history show that high-skilled immigration is essential for U.S. innovation, particularly in high tech industries like semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and pharmaceuticals that have been a focus of recent industrial policy proposals.

Other research shows that U.S. restrictions on high-skilled immigration not only push multinational corporations to move their R&D activities offshore, but also can benefit China, which traditionally struggles to attract human capital (especially in semiconductors). These benefits and many others thus make substantial expansions of high-skilled immigration one of the bigger no-brainer policies that the United States could adopt to bolster domestic innovation and corporate R&D spending.

Yet the crucial role that immigration plays in this regard is mostly ignored on the Trump-friendly right, including in the many conservative proposals to boost essential U.S. industries—proposals that instead rely on very unconservative policy levers like subsidies, regulation, and economic planning. Conservative industrial policy advocates can even be outright hostile to immigration when it’s presented (rightly) as an important policy lever for boosting future U.S. growth and productivity. And similar blind spots exist, as we’ve discussed, for imports (especially as part of global supply chains), foreign direct investment, and capital markets—all of which support, as the COVID-19 vaccines recently retaught us, the American economy and especially innovation-intensive U.S. industries.

The omission of these key ingredients in the U.S. economy’s “special sauce,” along with strained attempts to pin various economic ills on various preordained cultural villains, indicates that the goal for many New Right policy advocates is not so much making good, coherent policy, but making policy that checks the right cultural and political (both Trump-related) boxes, regardless of the policies’ actual efficacy. (It also undermines the alleged seriousness of the supposed problems the New Right says we’re facing, but that’s an issue for another time.) Maybe this approach will sell in the new GOP and even win a few votes. On the latter, I’m firmly on record as skeptical. If I’m wrong, however, it sure doesn’t bode well for Republican policy and, if the GOP regains control of government again, the U.S. economy. Unserious signaling might not matter when it comes to selecting a party apparatchik or filing a soon-forgotten messaging bill, but—to the extent that such policies are actually implemented—it can.

And we’d all be worse off for it.

Chart(s) of the Week

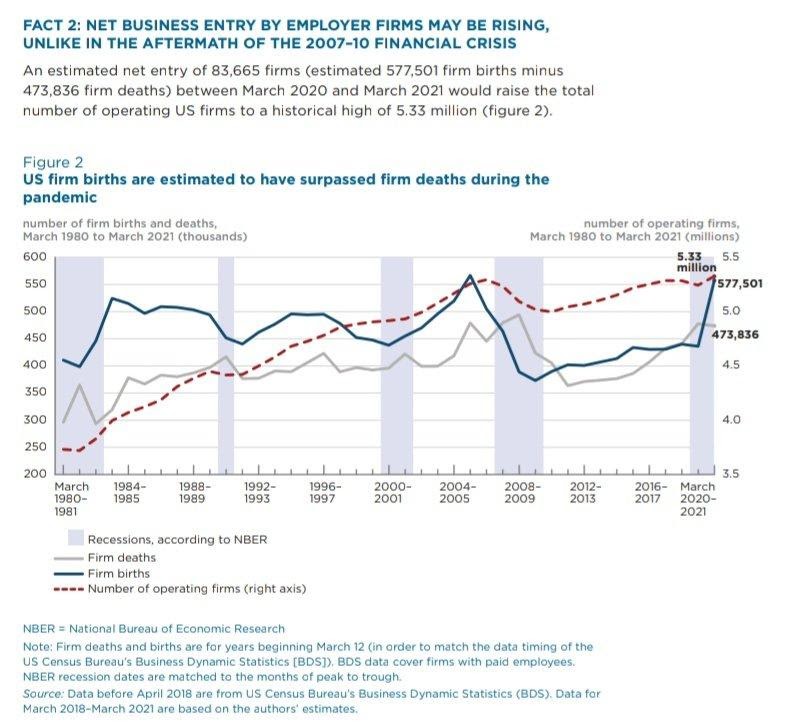

Business dynamism during the pandemic (source)

Home prices in Austin have gotten a little nuts. (Source)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.