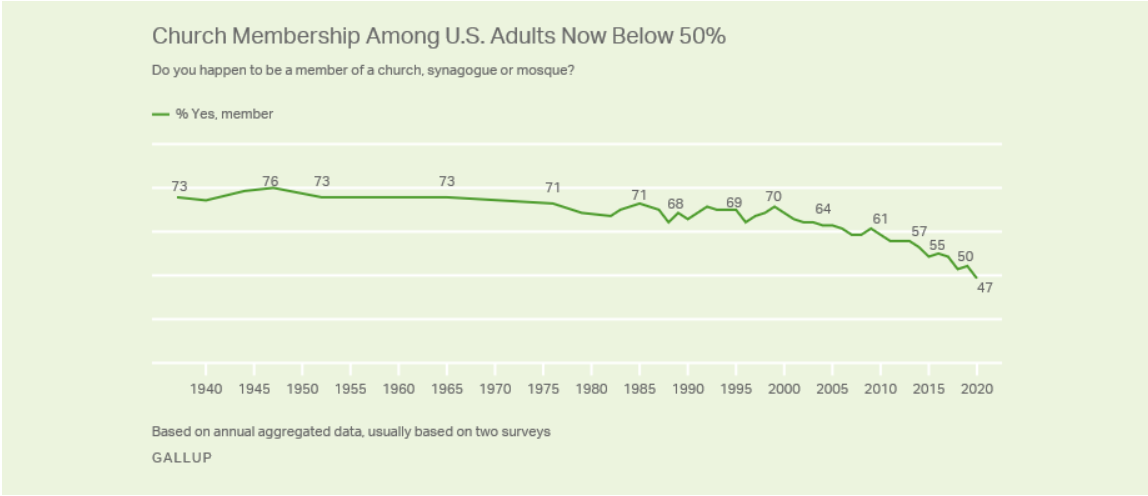

In many ways the timing couldn’t be more symbolic. On Monday, March 29—in the midst of Holy Week and the very day after Palm Sunday—Gallup released polling that conclusively and strikingly demonstrated the rapid decline and fall of American religion. For the very first time church membership among American adults fell below 50 percent. And the decline has been strikingly swift. Between 1940 and 2000, membership in a church, synagogue, or mosque hovered around 70 percent. Then the new century arrived:

There is so much pain and loss summed up in that green line. It’s symbolic of the forces that have buffeted the church from without, including the rise of hostile secular ideologies that scorn traditional faith and seek to suppress its practice. But it’s more symbolic of the forces that have shredded it from within—of the scandals and abuses that have made a mockery of our professed beliefs.

Regardless of the cause, we’re often left with the same emotions. So many Christians fear a seemingly inevitable secular future. There’s a deep anxiety for our children and grandchildren, and real alarm that the church may face deepening isolation and perhaps even persecution.

But that green line also reminds me of something else. It reminds me of Holy Week itself. In the Christian calendar, Easter is the culminating day of a week of observances, with each observance marking an increasingly grim reality. The arc of the week represents—in the world’s eyes—the total collapse of a public ministry and the end of a particular dream of an earthly messiah, of a revolutionary king.

Holy Week begins with Palm Sunday, the “triumphal entry” into Jerusalem. The book of Matthew records the scene. Jesus rode on a donkey’s back, to the roar of the crowd:

Most of the crowd spread their cloaks on the road, and others cut branches from the trees and spread them on the road. And the crowds that went before him and that followed him were shouting, “Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest!” And when he entered Jerusalem, the whole city was stirred up, saying, “Who is this?” And the crowds said, “This is the prophet Jesus, from Nazareth of Galilee.”

For a moment, Christ even seems to play the role of the supernatural revolutionary. He not only purges the Temple of the crooks and conmen, he causes the blind to see and the lame to walk.

But then the collapse begins. Within days, resistance leads to a plot, then to an arrest. After the arrest, the same people who roared their approval days before call for his life. Peter, his most militantly faithful follower, goes from defending Christ with his sword to emphatically and repeatedly denying him in his hours of greatest need.

Ultimately Jesus is executed. It seemed Roman authorities had swatted aside yet another low-rent revolutionary. On Good Friday, Christ died and so did that particular dream of an earthly king. To the extent that Jesus would remain relevant, perhaps some of his teachings would linger. A scattered few disciples could keep a tiny flame lit, for a time, before his name would be lost forever.

We know the rest of the story, of course. Good Friday was not the end. Sunday came. But we forget how the resurrection manifested itself—not as a triumphant, superhero-style act of power, but instead as a quiet return, first to women who occupied a marginalized place in the Roman Empire and Jewish life. Even as the resurrected Christ expanded his circle of influence, it still remained small, and he left his Gospel in the hands of a tiny number of men and women who seemed stuck in the backwaters of the world.

Again, all of this is totally contrary to our innate sense of how we transform nations and exercise power. Christ figures are common in fiction, but even for those ultimately vulnerable enough to die and return, their return is typically a magnificent exercise of raw strength.

We simply cannot seem to resist the grab for power, and when we make that grab—Christ came and now Constantine can reign—we fail and fall. Think of this past year. One after another, institutions of Christian power have faced moments of reckoning and shame.

Easter, however, reminds us that death is a prelude to resurrection—to a very particular form of new life, a life designed to imitate the sacrifice that led to death. In the crucifixion story itself we see a model for how we’re to respond, a human example of the godly response to Christ’s sacrifice.

Catholics call him Saint Dismas. Protestants often refer to him as simply the “Good Thief.” But a better description of Dismas is found in the NIV version of Matthew 27. The men crucified alongside Jesus are called “rebels.” In context, this makes sense. Jesus, the alleged “King of the Jews,” was crucified right next to equivalent criminals—those who would rebel against the authority of Rome.

But in a moment of blinding clarity and miraculous faith, Dismas looks at Christ in his earthly weakness and perceives his eternal strength. “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom,” he says. Which kingdom? The Kingdom that comes “not by might, nor by power” but by the Spirit of a living, resurrected God.

As I look back on the arc of Christian history, it is uncanny how many efforts to achieve change or to preserve influence by might and power have turned to ashes and dust. They’re akin to the Holy Week failure of Christ’s fickle followers to transform the world through the movement they imagined. In so many ways we deserve our decline.

But the resurrection is the response. It’s the great news of the total reset of our expectations and the union with Christ in his true kingdom. Let’s return to Peter, the apostle who embodied the death of one dream and the birth of something entirely different.

Peter never gained the kingdom he fought to forge when he drew his sword to protect Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane. Instead, as Christian tradition has it, Christ’s resurrection and forgiveness led Peter to his own cross, to crucifixion at Nero’s command.

One can look back at the Gallup graph above and perceive a kind of institutional death in process. But the Christian faith is a resurrection faith. It is rooted in an eternal reality that not even death itself can prevail against the sovereignty and love of the Creator God. In rebirth, we change. We transform. Or, to put it another way, when it comes to the health and strength of the American church, Good Friday is in process. But fear not: We know that Sunday is on its way.

One last thing …

Longtime readers know that I love reimagined versions of old hymns. This version, from Carrie Underwood’s new album, combines old and new, and the hymn itself beautifully describes how we approach the risen Lord—just as we are:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.