One of the joys of being a writer is reading thoughtful responses to your work—especially from people you respect. It’s hard to respect a columnist more than I respect Ross Douthat, and so I was happy to see he engaged at length a few days ago with a column I wrote in Time about teaching American history honestly, warts and all, rather than with the purpose of creating new patriots. Ross wrote to “disagree mildly.”

If I had to sum up Ross’s argument in a sentence, it’d be, “Sure, teach everything, but lay the ‘patriotic foundation’ first. There’s a lot of good in the American story. Lead with that.” It’s a good piece, and he makes a good argument, but I want to engage with something else first. In his piece, Ross described me as “the famous conservative critic of conservatism.”

I chuckled. Mainly at the “famous” part. But then I thought for a moment. Is that what I am? A conservative critic of conservatism? This whole time I thought I was a conservative defender of conservatism against populism and corruption. That’s the concept of the remnant, the “Hey, we’re still here!” band of brothers and sisters who’ve remained faithful to a particular Before Times definition of conservatism that we believe still means something—something good.

As life has opened up, I’ve gotten back on the road, and I’m connecting again with old friends in the conservative movement. And I’m getting a repeated question: “Are you still with us?” I’m starting to answer with a question of my own. “I remember when we believed the same things. Are you still with me?”

In the Before Times, I experienced conservatism on two axes. We’ll call them ideological and dispositional. The ideological element was relatively easy to articulate. I stood (and stand) much closer to the libertarian side of the conservative spectrum. This meant defending civil liberties (including the right to life of the unborn), respecting economic freedom, and defaulting power to local levels as much as possible. School reform, for example, should center more on enhancing school choice than on commandeering the existing, largely hostile public school bureaucracy.

I was (and am) deeply skeptical of central planning, and I believe limiting the power of the state over human liberty is a just and wise policy goal all by itself. In international affairs, however, I believed in American power and presence. Strong treaties. Forward deployments. These measures not only kept America safe, they helped prevent great power war for three full generations.

That’s the ideology. What about the disposition? By “disposition” I mean the way in which a person approaches the public square and the way in which a person conducts their affairs. Here I put a high premium on decency, good character, and an open mind.

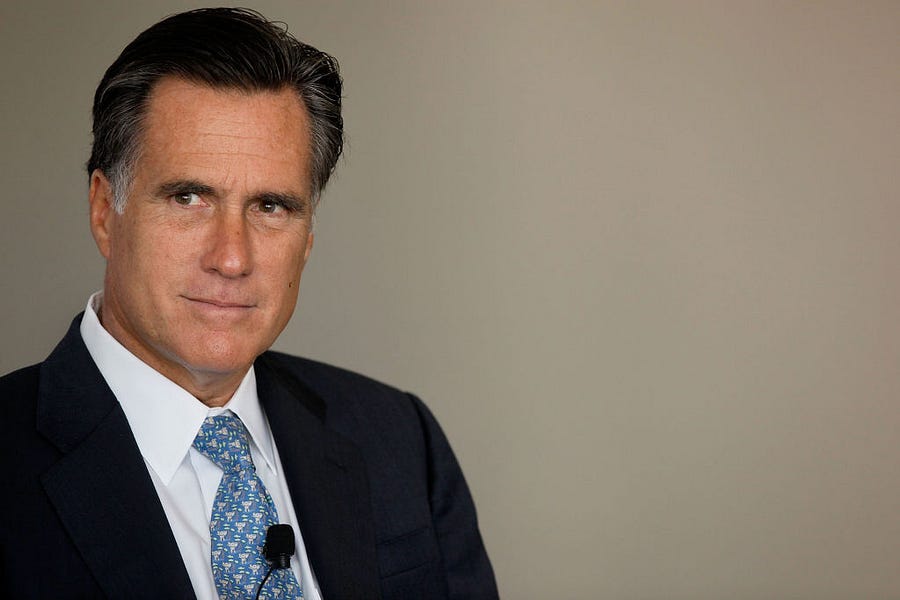

This is the core reason why I weathered the critique of my more ideological friends and supported Mitt Romney in both 2008 and 2012. While he didn’t line up with me ideologically as much as other GOP politicians might have, his core character was (and is) exemplary, and his character qualities (I believed) would have made him a good and perhaps even great president.

My experience of the conservative movement is that it has shifted on both axes, rather decisively. Ideologically, injecting aggressive big-government populism into the ideological stew has rendered conservatism both more ideologically incoherent in its policy aims and more progressive in its vision of state power.

Economic nationalists seek more central planning. Populist critics of Big Tech seek to undermine decades of conservative-supported First Amendment precedent to blur the lines between corporation and state. Anti-woke activists write speech codes. “America First” isolationists seek to pull troops back home and call into question relationships with even strong allies.

I’m open to anyone who wants to question any aspect of traditional conservative dogma. Ideological inflexibility in the face of changing challenges can be its own vice. Closed-mindedness certainly is. In fact, Ross faced his own round of unfair attacks in the Before Times, when he and a small band of lonely comrades wisely argued that the GOP should reorient its economic policies more towards middle-class and working-class voters.

Those were the days of enforced ideological conformity, when right-wing radio hunted RINOs based more on policy than personal loyalty to any politician. Indeed, there has never been a perfect time for American conservatism. There are better times, and there are worse times.

It remains a fact, however, that Trumpist populism is significantly different from classical conservatism, and its view of state power has moved significantly to the left. Limiting state power is no longer an objective. Expanding the power of the state and putting it in service of right-wing policy goals is a core tenet of the New Right.

But just as the conservative movement has become more flexible ideologically (for good and ill), it has become less flexible dispositionally. In fact, disposition now decisively trumps ideology in the self-definition of the right. You. Must. Fight. The will to fight trumps commitments to truth, character, principle, and even basic competence. Democrats delenda est.

At the edges of the right, horseshoe theory rules. How different are Antifa and the Proud Boys, really? They’re both willing to storm government buildings, for example. But the hard right escalated to something the hard left still hasn’t done—storming the Capitol to try to overthrow the results of an American election.

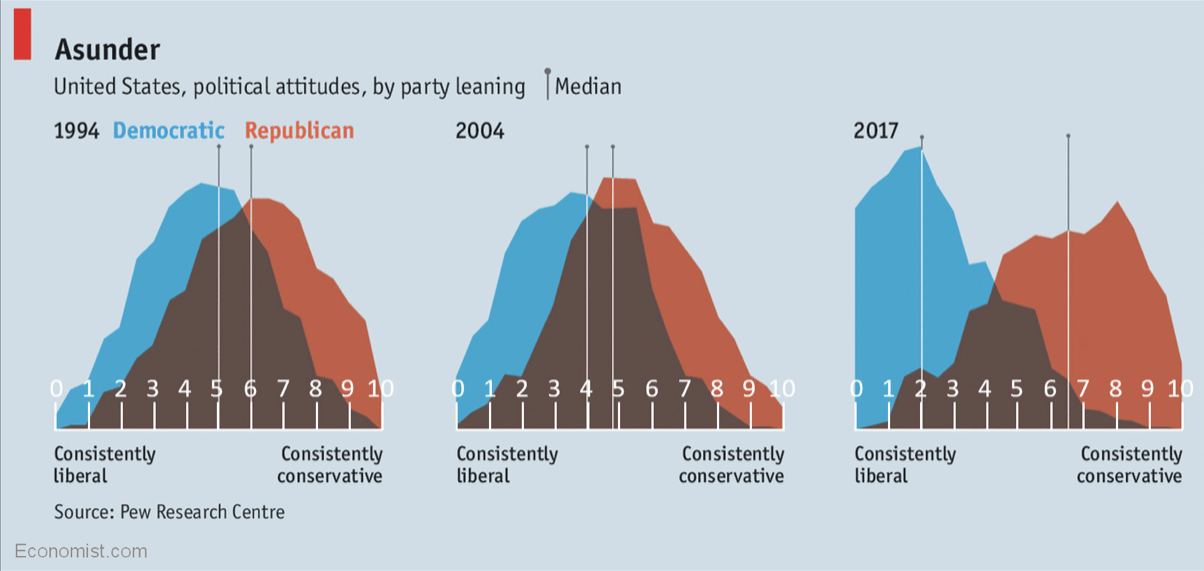

This is where I have my own quibbles with Kevin Drum’s much-discussed essay where he asserted, “If you hate the culture wars, blame liberals.” I completely agree with the data he shares indicating that the left has made larger ideological moves than the right. He shares this vivid chart:

But that’s the ideological axis. The dispositional axis is different. Yes, the far left can be vicious and violent. Cancel culture is real, and riots roiled American streets. But right-wing cancel culture is real as well, and so is right-wing political violence. Moreover, at the end of the day, only one party enthusiastically inflicted Donald Trump on the American body politic in not one, but two (and soon enough, maybe three) presidential elections.

As much as one might try to rationalize the turn to Trump as a response to the Democrats’ move to the left (and the increasing intolerance of the hard left), at the end of the day it’s hard to credibly stand beside Trump and shout, “But you’re the real bullies!”

Progressives have made bold moves on the ideological axis, and their left-wing base has ramped up its aggressive disposition. Republicans have made modest moves on the ideological axis (and in some cases have become more progressive), but they’ve made extreme changes in disposition, and the disposition is so dominant that it has virtually captured the ideology. Increasingly, the policy is what the disposition demands.

That’s where I get off the bus. Any intellectual movement can and should tolerate a broad range of ideological arguments, and a political party has to have a bigger tent still, but basic commitments to truth, decency, competence, and the rule of law itself must remain. A “conservative” movement isn’t remotely conservative if it doesn’t conserve these foundational, civilizational values.

Another thing …

I’m not done with Ross yet! When I read his piece, I immediately wondered if he’d write the same essay if he lived in deep-red America. Each tribe is beset by its own extremes, and the extremism we experience most directly can’t help but shape our experiences. In deep-blue America there is sometimes a tendency to teach history (especially to older students) through the prism of America’s sins. Deep-red America often yields to the opposite temptation. The two regions need different kinds of correctives.

But there’s something else that I questioned. Here’s the heart of Ross’s argument:

If historical education doesn’t begin with what’s inspiring, a sense of real affection may never take root—risking not just patriotism but a basic interest in the past.

He continues:

Whereas if you teach kids first that the past is filled with people who did remarkable, admirable, courageous things—acts of endurance and creation that seem beyond our own capacity—then you can build the awareness of French’s bad-and-ugly organically, filling out the picture through middle and high school, leaving both a love of country and a fascination with the past intact.

Ross also notes that the story of American heroism is rich with stories of black Americans. He singles out Harriet Tubman and Martin Luther King Jr. But doesn’t telling their story necessitate also telling the story of shocking injustice, and telling it side-by-side with the early introduction of their courage?

Speaking as the father of a black daughter, I can tell you from first-hand experience that a response to, for example, the story of Rosa Parks isn’t always, “Yay Rosa Parks!” It’s “Wait, daddy. They didn’t let people like me ride on the front of the bus?” And that question leads to a much longer conversation. And when your young daughter experiences racial discrimination, it can come as a truly shocking bolt out of the blue unless she is prepared with at least a basic knowledge of one of the persistent founding maladies of the land in which she lives.

I happen to think the directional story of America is good. The dark realities of 1619 and the worldview it represented encountered the startling aspirations of 1776, and slowly, haltingly, and often violently, the aspirations of 1776 are prevailing. They’ve prevailed over slavery. They’ve prevailed over Jim Crow. They’re prevailing over the legacies of those dreadful injustices. But to teach about MLK, one must also teach about Bull Connor and George Wallace, and in so doing students will learn that part of the story of American courage is its necessity to triumph over American sin.

Ross and I are mostly in the same place. He wants to teach all of our history. I want to teach all of our history. But even if you begin with American heroes, you’ll have to learn what they stood against, and especially for students of color that knowledge can be every bit as jolting as, say, Tubman’s courage is inspiring.

One last thing …

I’m traveling today, and I’m bitterly disappointed that I won’t be joining this week’s Dispatch Podcast to talk about one of my favorite topics. Space! I’m still counting on Elon to get me to Mars, but Jeff Bezos launched himself into the void today, and it was fun to watch. I love to see the energy and creativity of American private enterprise applied to space travel. (And it was great to see 82 year-old Mary Wallace Funk finally get her opportunity to experience space. Her story is both frustrating and amazing.) For those who missed the launch, enjoy!

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.