Ever since the start of the coronavirus crisis, I’ve had a number of readers request a Sunday newsletter addressing Christians and conspiracy theories. Until now, I’ve resisted. The honest reason is that I was too optimistic. As the inexorable reality of the pandemic bore down upon us all, I’d hoped (prayed) that the conspiracies would fade.

They have not. At least not in my world. I still see references to the utterly discredited “Plandemic” video. I still see claims the coronavirus death tolls are being intentionally artificially inflated. There are rampant rumors of people receiving false positive test results when they never took a coronavirus test. There have long been claims that the lockdowns weren’t designed for public health, but rather to destroy the Trump economy.

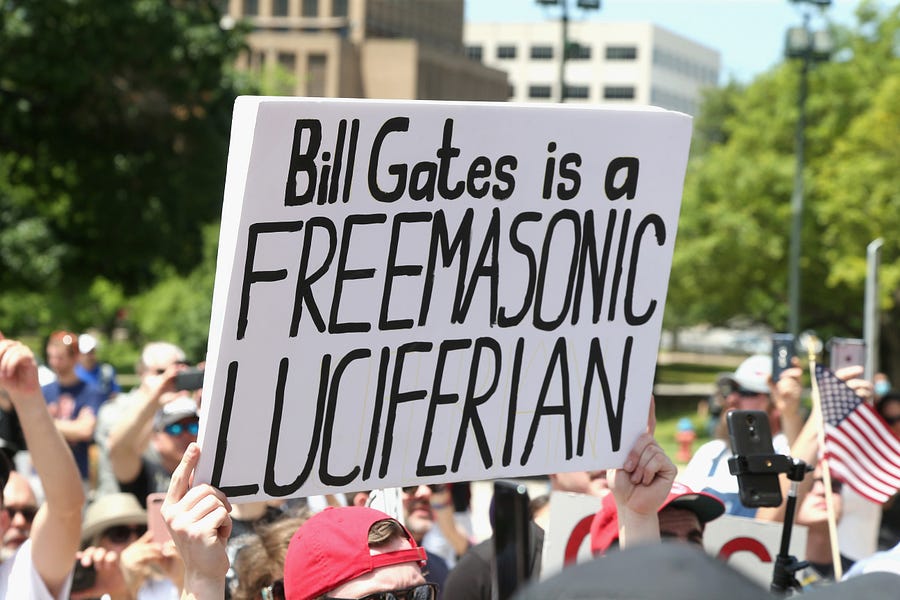

And I haven’t even touched all the wild claims about masks or the alleged microchips in the “Gates vaccine.”

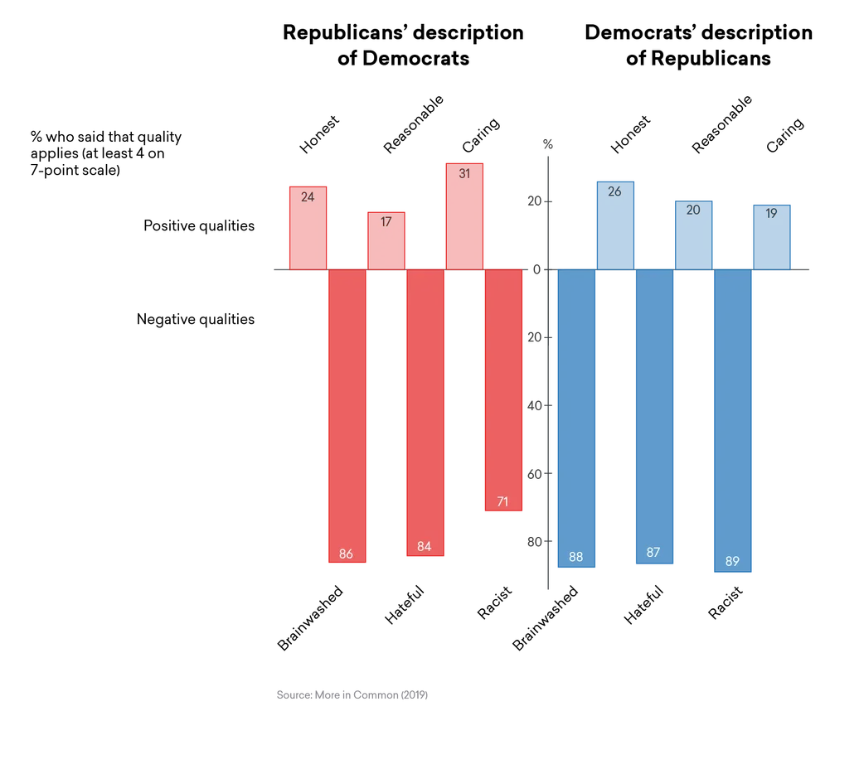

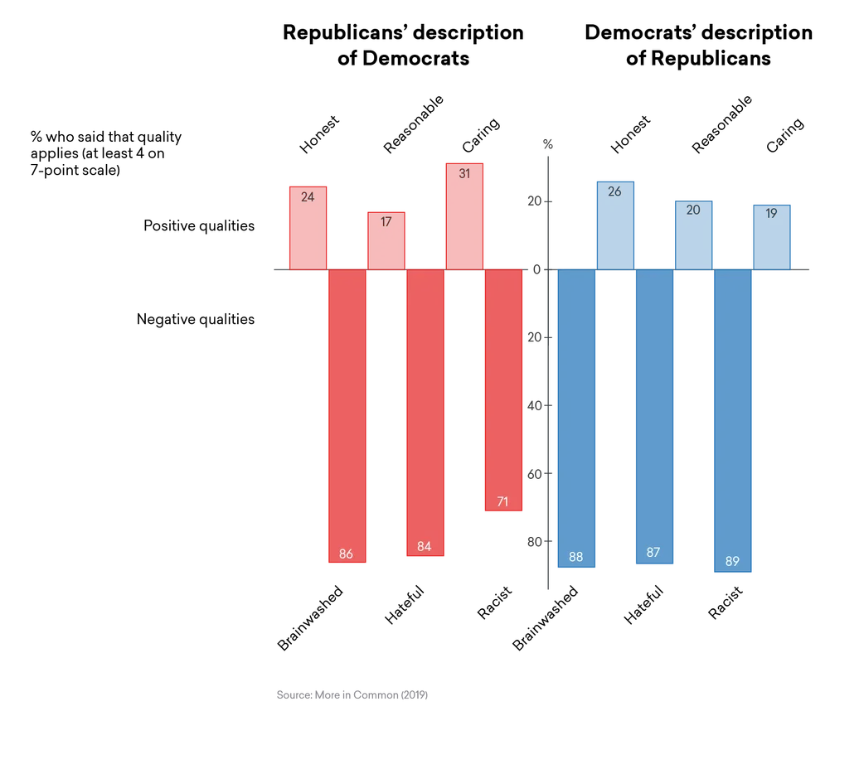

I can list some of the cultural and sociological reasons for the willingness to believe, well, virtually anything about our political and cultural opponents. Combine negative polarization—where partisan Americans often believe the worst about their opponents—with undeniable political and media failures, and you’ve got a recipe for suspicion and mistrust that can spiral out of control.

I mean, look at these numbers from my friends at the More in Common project:

The good news is that we’re often wildly wrong about the nefarious intentions or beliefs of our political opponents. The bad news is that there does not seem to be a Christian exception to these polarizing trends. Our community isn’t so much resisting those trends, it’s empowering them.

For example, white Evangelical voters went from the community least tolerant of unethical politicians to the community most tolerant, and they did so in five short years:

Because we’re in election season, and because I’m one of the few national columnists who’s both Evangelical and lives deep in the heart of Republican Evangelical America, I’m constantly asked some version of the same question, “What the heck is going on?”

The short answer surprises folks who don’t spend time with Evangelicals. As a general rule, all too many Christians do not possess any form of political theology beyond a commitment to a certain set of issues. As a result, their distinct identity within the body politic is frequently defined by those issues alone rather than by their character or conduct.

Let me explain it like this—if you’re a church-going American Christian, you tend to build up a reasonably robust theology of Christianity in your marriage, in your workplace, or in your school. And you don’t obtain your understanding of how to be a Godly husband, father, employee, or boss merely by reading scripture—though scripture should be your foundation. By the time you reach middle age, you’ve been exposed to countless books, Sunday School lessons, speaking series, YouTubes, personal testimonies, retreats, and small group study sessions that help you engage with virtually every life challenge.

This is not the case with politics. Not at all.

With politics, the theological “training” consists mainly of education about issues and controversies that Christians should be aware of and concerned about. Conservative Christian political engagement, for example, is largely defined by the defense of religious liberty and the protection of the unborn. These issues are important, and our faith principles should inform our political positions.

We do not, however, spend nearly enough time learning how to live as political beings within a political community. We connect our faith with our political objectives but do far less work connecting our faith to our political conduct or our theological priorities.. This is not the way we engage with other significant areas of life.

Christian teaching about our lives in our workplaces is not primarily about how to obtain a promotion, how to invest our money, or how to start a business. In other words, it’s not about the objectives of economic engagement, though those objectives are important. Instead, the focus is on ministering to colleagues, cultivating faith in adversity, and generally learning how to be salt and light even in sometimes hostile or intimidating environments.

Similarly, student ministries aren’t about teaching students how to get good grades or to become accomplished scholars. Instead they address how a student can maintain and grow his faith and act as an evangelist and servant to his classmates even when growing up is hard, and the pressures to conform to the world are great.

You get the idea—time and again, in critical areas of life, Christians are rightly taught that the objective of the secular activity is less important than the manner with which you engage with your community. In every context commandments regarding our conduct aren’t conditioned on levels of adversity. Duties of honesty and kindness don’t slide away when bankruptcies loom or failures threaten our plans—even when those failures can have grave consequences for our lives.

If you think, “Well, of course all this teaching should naturally translate to politics” then you’re forgetting the inexorable pull of our fallen nature. At every turn, the enemy of our souls rejects the upside-down logic of scripture (“The last shall be first; to gain our lives we must lose our lives; love your enemies”). A voice whispers in our ears, saying, “You could be kind, but you’ll lose. You could stand against lies, but you’ll fail. All your worthy goals will turn to ash.”

And so—in the absence of the same kind of teaching that we receive in other vital areas of life—we’re prone to conduct ourselves in politics differently than we do in virtually anywhere else. In fact, I’m sure many readers see it all the time.

There’s your good friend, the person who’d give you the shirt off his back, show up any hour to help a person in need, and would never compromise his values in his marriage or his business—yet there he is, absolutely flaming the libs on Facebook, rejecting the “Gates Vaccine,” and reveling in the most outrageous attacks on his political opponents.

Or there’s the incredibly sweet woman at church. She volunteers in the nursery. She shows up for every community work day to serve the city’s poorest and most disadvantaged kids. And yet she’ll send you Alex Jones clips, trying to prove to you how bad “they” (Democrats) really are.

And some of these same folks, when you urge kindness and decency in political engagement will look at you incredulously. “Don’t you remember what they did to Mitt Romney?” The message is clear—in the realm of politics, personal values matter mainly when they work. Unlike in their businesses, marriages, and schools, compliance with commandments is conditioned on immediate results.

I’m not making these folks up. I know them. I love them. They’re not deplorable, but in this important area of life, they say deplorable things, and they’re spreading those deplorable words far and wide.

This is a long digression to make a simple point: Unless the church can address its deep and more fundamental failure of moral and theological instruction in politics, many of its leaders and thinkers will continue to pay whack-a-mole with the symptoms of the underlying disease. And make no mistake, conspiracy theories represent one of those symptoms.

After all, what is a conspiracy theory but a lie? It comprehensively and grievously violates the Ninth Commandment. A conspiracy theorist bears false witness against his neighbors—against his fellow citizens. He accuses them of grievous sins, he destroys their good name, and he can even incite deadly violence.

“But David,” you respond, “the conspiracy theorist doesn’t think he’s lying.” Yes, of course, but that’s precisely where our moral and theological instruction has failed. If we merely say, “Do not lie,” we’ve not gone far enough.

The Ninth Commandment is no mere admonition against falsehood. Comprehensive duties flow from that command. The failure to understand the full breadth of our Ninth Commandment obligations (especially when combined with fear and anger) renders believers vulnerable to—and ready to spread—the most heinous of lies.

And what are those more complete obligations? I love how the Westminster Larger Catechism articulates our task:

The duties required in the ninth commandment are, the preserving and promoting of truth between man and man, and the good name of our neighbor, as well as our own; appearing and standing for the truth; and from the heart, sincerely, freely, clearly, and fully, speaking the truth, and only the truth, in matters of judgment and justice, and in all other things whatsoever; a charitable esteem of our neighbors; loving, desiring, and rejoicing in their good name; sorrowing for, and covering of their infirmities; freely acknowledging of their gifts and graces, defending their innocency; a ready receiving of a good report, and unwillingness to admit of an evil report, concerning them; discouraging talebearers, flatterers, and slanderers; love and care of our own good name, and defending it when need requireth; keeping of lawful promises; studying and practicing of whatsoever things are true, honest, lovely, and of good report. (Emphasis added; footnotes omitted.)

If a person understands those obligations—if he truly comprehends his duty to his neighbor—will he be a sponge for the worst and most paranoid accusations? Absolutely not. He’ll be inoculated against them. That’s where the church addresses conspiracy theories. That’s a key place where the church addresses enmity and anger between left and right.

Sure, let’s forward fact-checks that correct our friends and neighbors, but don’t believe for a second that we’re changing anything meaningful until the duties articulated above are embedded in our hearts and minds.

What does it mean to have an “unwillingness to admit of an evil report” concerning our political opponents? It doesn’t mean being gullible. It doesn’t mean rejecting the idea that our opponents can do grievous, scandalous things. It means addressing claims of wrongdoing with charitable skepticism—and the wilder the claim, the greater the skepticism. Our moral posture should deter slander.

We understand this obligation with our friends and allies. I’ve seen that some of the same people who forward the worst allegations against Bill Gates or the “deep state” or Anthony Fauci also reacted with extreme outrage at all those who jumped to conclusions about Brett Kavanaugh or immediately attacked the kids from Covington Catholic. They could see the “slandering” or the “talebearing” by their political opponents. They cannot see it in themselves.

We can be frustrated at their blindness. We can be furious at their hypocrisy. But we have to realize a sad failure of the church. They do not see because they were never taught to look.

One more thing …

Rep. John Lewis died yesterday. He was an American hero. Specifically, he was also a Christian American hero, who—in a time of injustice and oppression that we can scarcely comprehend today—responded with courage, dignity, and peace in the face of vicious violence. In the video below, he reflects on one of the most momentous days in modern American history, March 7, 1965—“Bloody Sunday” in Selma, Alabama.

As he explains in the video, he demonstrated his love for this country not through any act of aggression, but through his willingness to die, to lay down his life. Watch and remember what it was like when people of faith changed this nation through the most courageous acts of peace that I’ve ever seen:

And here is Lewis, speaking in 2004 about the power of faith, forgiveness, and reconciliation in those perilous days — and note his emphasis on how they would engage, not just why they resisted:

Are you concerned that the religious aspects of the movement are being lost the further we get from those days?

I’m deeply concerned that many people today fail to recognize that the movement was built on deep-seated religious convictions, and the movement grew out of a sense of faith — faith in God and faith in one’s fellow human beings. From time to time, I make a point, trying to take people back, and especially young people, and those of us not so young, back to the roots of the movement. During those early days, we didn’t study the Constitution, the Supreme Court decision of 1954. We studied the great religions of the world. We discussed and debated the teachings of the great teacher. And we would ask questions about what would Jesus do. In preparing for the sit-ins, we felt that the message was one of love — the message of love in action: don’t hate. If someone hits you, don’t strike back. Just turn the other side. Be prepared to forgive. That’s not anything any Constitution say anything about forgiveness. It is straight from the Scripture: reconciliation. So the movement, the early foundation, the early teaching of the movement was based on the Scripture, the teaching of Jesus, the teaching of Gandhi and others. You have to remind people over and over again that some of us saw our involvement in the civil rights movement as an extension of our faith.

Rest in peace, John Lewis. One of America’s great citizens has gone home to his Savior.

One last thing …

After Aretha Franklin died in 2018, Rep. Lewis said that without her “the Civil Rights Movement would have been a bird without wings.” Lewis singled out his memory of Franklin singing “Precious Lord Take My Hand” at Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral. Here’s the best-sounding version I could find. What a singular talent. Enjoy:

Photograph by Gary Miller/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.