Let me start by admitting two things. First, I’m incredibly tired of the online wars over critical race theory. Second, I know I’m a total hypocrite when I lament the obsession, because I seem to be writing about it all the time. But I can’t help myself. The controversy touches on a number of issues where I have an abundant amount of experience—not just with critical race theory itself (I first learned its basic elements thirty years ago and have been writing about it or responding to it ever since), but also on speech codes, free speech in higher education, and the intersection between civil rights laws and the First Amendment.

Moreover, as I noted earlier this week, I co-wrote an op-ed in the New York Times with Kmele Foster, Thomas Chatterton Williams, and Jason Stanley that argues the attempt to ban the expression of ideas through the broad, vague “anti-CRT” laws currently being proposed (and passed) across the nation is a bad idea. Even if lawful (which is debatable in some circumstances), such bans are unwise. As we wrote in the op-ed, a better proposed course of action in response to undeniable abuses is two-fold:

Propose better curriculums and enforce existing civil rights laws. Title VI and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, and they are rooted in a considerable body of case law that provides administrators with far more concrete guidance on how to proceed. In fact, there is already an Education Department Office of Civil Rights complaint and a federal lawsuit aimed at programs that allegedly attempt to place students or teachers into racial affinity groups.

There has been a staggering amount of anger, controversy, and debate in response. For example, good friends and thoughtful folks at National Review have taken aim at my position again and again and again and again and again. But as I read these contributions (and appreciated them! Responding to the excesses of critical race theory is a tough issue that merits serious debate), I began to notice something they all had in common. See if you notice as well.

In his thoughtful piece about the Texas law, Stanley Kurtz says this about a key part of the statute:

This phrasing could potentially prevent even discussion of the various concepts, which would indeed run afoul of our culture of free expression, despite being legally permissible.

In a short critique of our op-ed, Rich Lowry notes that the same Texas law is allegedly “going to get a scrub in the Texas special session” and says “it’s totally legitimate to worry about the wording of the laws,” but then accuses us (wrongly, in my view) of misrepresenting their meaning.

In his own piece which attempts to explain what I “get wrong” about CRT in schools, my friend Dan McLaughlin says, “There are fair criticisms of how some of the bills that would enact such bans have been drafted; legislation is a blunt instrument with which to control a curriculum, and some of the initial efforts have been more careful than others.”

One never, ever wants to run afoul of Kevin Williamson’s sharp pen, and he’s weighed in as well with a characteristically interesting and thought-provoking argument. It includes two interesting comments:

French, Foster, et al. bring up important concerns about the way anti-CRT laws are structured and the assumptions behind them, but that is not a case against anti-CRT laws—it is a case against badly written and clumsily conceived anti-CRT laws.

And:

The anti-CRT laws, coarse and genuinely stupid as they often are, are an attempt to change that ideological balance, or at least to put some limit on how far to the left the public schools will tilt.

I can’t say that I know Cameron Hilditch, but he penned a lengthy endorsement of anti-CRT laws that nonetheless contained this rather amusing line: “It’s true that the laws in question could have been drafted better, but it is better to have them on the statute book than to have none whatsoever.”

Finally, Dan McLaughlin weighed in again, this time pointing readers to my friend Greg Lukianoff’s outstanding, extended discussion of the topic. Dan repeats Greg’s warning “that poorly-drafted laws can end up banning the teaching of things that the legislators never intended to ban, and can lead to confusion and discord at the school level.”

I think my point is clear. The defenses of anti-CRT laws are time and again running aground on the rocky shoals of … the actual anti-CRT laws. Welcome to the incredible difficulty of drafting speech codes. For decades, some of the smartest minds in higher education, Big Tech, and elsewhere have been trying hard to draft laws that ban the ideas they don’t like without sweeping too broadly or creating unintended consequences.

The allure is obvious. If we have the power to ban harmful speech, why not ban harmful speech? But the execution is always clumsy and dangerous if it’s broad, and narrow to the point of irrelevance if it’s precise. Another National Review pal, Ramesh Ponnuru, put things well in his own contribution to the debate in Bloomberg. “But regulation can be defensible in principle,” he says, “without a particular regulation being wise in practice. Some of the provisions in these bills are vague and sweeping.”

Yes, yes they are. But then Ramesh makes this vital point: “The more precisely these laws are written, though, the less they will proscribe and the easier they will be to evade.”

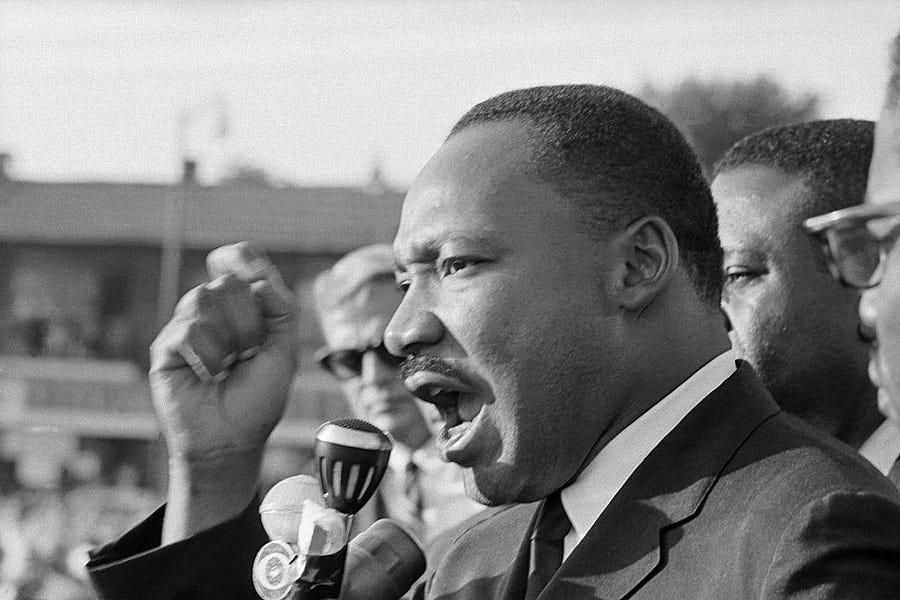

Yup. And that’s exactly why I circle back to my proposal—better curriculums and civil rights litigation. Thus you give teachers the confidence to teach something concrete and real without creating a fear that even their own course materials might suddenly be illegal. Let’s take the book excerpt below. It would now be illegal to include under multiple anti-CRT bills, which often ban including content that argues that a person, by virtue of their race or sex, “is inherently privileged, racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or subconsciously”:

Critical race theory? Nope. Martin Luther King Jr., in Where Do We Go From Here? I’m sorry, but if you’re legally prohibited from teaching King in full, then there is something gravely wrong with your state law. Kentucky’s proposed bill would ban even an “informal” discussion of that excerpt of King’s work.

And now let’s turn back to litigation. I wrote a piece recognizing the threat of CRT abuse (I called it “toxic wokeness”) months before the controversy over anti-CRT laws began its hostile takeover of our national discourse. Here was the key graph:

It just might be time for a [national litigation] effort aimed at the most illiberal and hyper-woke elements of critical theory in the workplace, in academia, and in the media. It is increasingly clear that many elements of modern academic and workplace orthodoxy (including punitive actions) are incompatible with the plain text and obvious meaning of federal civil rights laws.

Inadequate? I have personal experience with national litigation efforts that have achieved dramatic results. For example, in 2003 I launched the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education’s (FIRE) speech codes litigation project with a single case against Shippensburg University in Pennsylvania.

We had virtually no funding and had to fight for media attention. But by 2009, the effort had spread dramatically. More groups than FIRE had picked up the banner. And by 2021, the national landscape had changed. Here are the latest FIRE statistics (a “red light” rating indicates the school has a policy that “clearly and substantially restricts freedom of speech.”):

The percentage of schools earning an overall “red light” rating in FIRE’s Spotlight database has gone down for the thirteenth year in a row—this year to 21.3%. This is approximately a three percentage point drop from last year, and is over 50 percentage points lower than the percentage of red light institutions in FIRE’s 2009 report.

And trust me, hundreds of schools didn’t change their policies because they faced hundreds of suits. Precedents were set, and precedents matter.

Lawsuits have another advantage. To prevail you have to present evidence. Claims are subject to rigorous scrutiny. At the moment, activists are proposing vague and broad reforms that sometimes contain “genuinely stupid” (Kevin Williamson’s words) language without any kind of rigorous process of discerning the extent and true nature of the perceived educational problem.

In other words, don’t listen to those who say that a call for litigation is a call for “surrender.” In a piece in American Mind so cleverly titled “David ‘Vichy’ French,” the writer asks this seemingly rhetorical question: Has any white person ever succeeded against the courts in a case where they were discriminated against for being white? She continues, “Of course, the open secret of civil rights law, which these authors know yet deny, is that it simply doesn’t apply to white people.”

This is just patently, provably false. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission itself highlights multiple cases where it intervened to stop so-called “reverse racism,” racial discrimination against white people (which includes racial discrimination against white Americans by black Americans). Here are two of the many:

In May 2009, the fast food giant Jack in the Box … agreed to pay $20,000 to settle a lawsuit alleging that the company did not take prompt action after a White hostess at its Nashville restaurant complained she was being harassed by Black co-workers who called her racial epithets and insulted her when they learned she was pregnant with a mixed-race child. EEOC v. Jack in the Box, No. 3:08-cv-009663 (M.D. Tenn. settled May 19, 2009).

In April 2009, a private historically Black college located in Columbia, S.C. agreed to settle a Title VII lawsuit alleging that it discriminated against three White faculty members because of their race when it failed to renew their teaching contracts for the 2005-2006 school year, effectively terminating them. EEOC v. Benedict College, No. 3:09-cv-00905-JFA-JRM (D.S.C. April 8, 2009).

So, to recap, even vigorous and thoughtful defenders of anti-CRT laws acknowledge deficiencies in the actual bills time and time again. Existing anti-CRT bills would ban teaching even some of the arguments of Martin Luther King. Narrowing the laws to make them precise would make them ineffective at their intended purpose. Federal laws already protect students and teachers (including white students and teachers) from racial discrimination and racial harassment. Oh, and if you want to teach history, civics, and law more effectively, there are abundant examples of high quality curricula you can propose and enact rather than banning ideas.

Parts of our nation are in the grips of a moral panic. Moral panics are not conducive to reasoned decision-making. It’s time to take a deep breath, slow down, and stop passing bad laws.

One last thing …

We’re two weeks away. The show that has warmed every American heart returns. We need Ted Lasso, now more than ever:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.