Because I’m a complete nerd and basically have no life, when I work out I don’t listen to music, I listen to political podcasts. Better-balanced people might lift weights to Metallica or run to Rush (yes, I’m dating myself), but not me. Yesterday I spent five miles on the roads of Franklin, Tennessee, listening to Ezra Klein talk to Ramesh Ponnuru about Ramesh’s idea that it would be better for the GOP to define itself as a “parents’ party” than a “workers’ party.”

Consider me on Team Ramesh. While I’m suspicious of technocratic tinkering as a tool for improving family life, I do think that we have enough information about some basic social trends to know that there are ways to support both life and marriage that 1) are attainable under a Democratic administration, but 2) may, over the long term, scramble American party alignments.

I’m talking about the combination of immigration and family allowances. A nation that continues to welcome legal immigrants is a nation that is essentially recruiting intact, marriage-based families to its shores. A nation that subsidizes child-bearing through family allowances is a nation that decreases abortion. At the same time, a country that is increasingly majority-minority may well end up more conservative, creating at least the potential of an enduring social conservative (or at least moderate) majority in the United States.

Let’s take each of these contentions in turn. Yesterday, the Institute for Family Studies (IFS) published a fascinating research brief demonstrating that “immigrant families tend to be more stable than families of native-born Americans.” The numbers are fascinating, and the differences are material:

Specifically, 72% of immigrants with children are still in their first marriage, whereas the share among native-born Americans is just 60%, according to a new Institute of Family Studies (IFS) analysis of census data.

Behind these numbers are the relatively higher marriage rates and lower divorce rates of immigrants in general. For every 1,000 unmarried immigrants ages 18 to 64 in 2019, 59 got married. The corresponding number for native-born Americans was 39. Likewise, only 13 out of 1000 married immigrants ages 18-64 got a divorce in 2019, compared with 20 out of 1000 among native-born Americans of [the] same age.

Even more fascinating is the reality that immigrant families are an outlier in another important respect—they defy the “conventional wisdom … that higher education and higher income drive family stability.” In other words, immigrant families are more stable even when they make less money and possess less education than corresponding native-born families. Why? The IFS conclusion is one word—“culture”:

Immigrants are more likely than native-born Americans to embrace a family-first mindset when it comes to marriage and children. In an IFS survey conducted in California, nearly 70% of immigrants said that it is very important for them to be married before having children, compared with 62% of native-born Californians. They also are more likely than native-born Californians to believe that couples with children should make every effort to stay married (50% vs.43%).

And that marriage culture benefits immigrants’ children, greatly:

The familism that immigrants embrace not only provides them a safe harbor when facing the challenges as newcomers, it also helps to provide a better environment for their children to advance in life. According to a recent analysis by IFS senior fellow Nicholas Zill, children of immigrants are doing surprisingly well in school: they are more likely to get “As” and are less likely to have behavior problems. The reason for their academic success is not because these children are from better-off families (in fact, the majority of them are not), it is partly because they are more likely to live in intact families with two married parents.

While not every immigrant demographic is equally likely to hail from intact families, it is fascinating to note that one answer to the public policy question: “How do we encourage a culture of marriage in the United States?” may well be a response that is an anathema to the current populist right: Maintain high levels of legal immigration.

(I do believe, at the same time, the nation should control its borders and regulate immigrant entry into the nation. A pro-immigration policy should never be confused with open borders.)

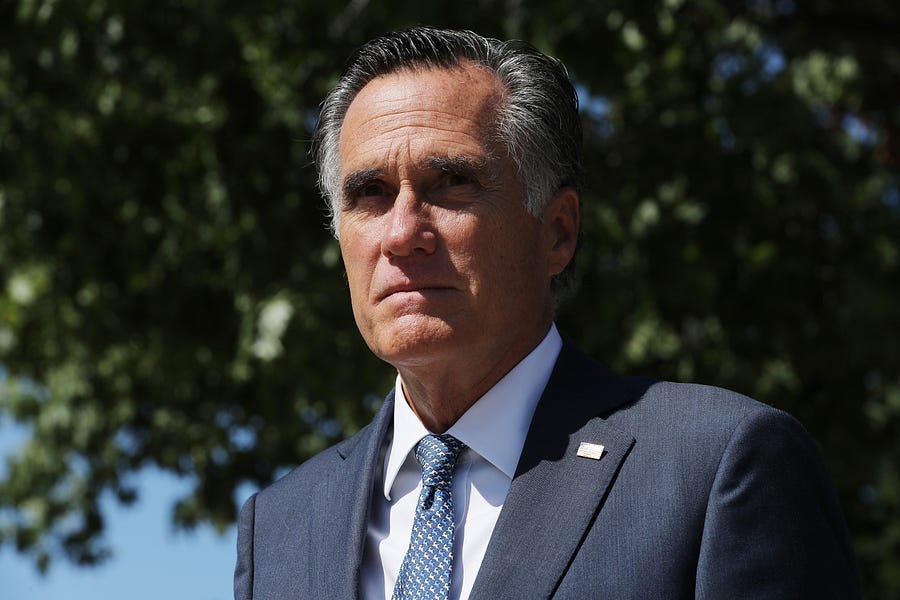

Now, let’s move on to family allowances. I’ve endorsed Mitt Romney’s child allowance proposal before, and I like it better every day (including after I listened to Ramesh and Ezra discuss it on Ezra’s podcast). In a nutshell, under the Romney plan, families would receive $4,200 per year per child (up to age six) and $3,000 per year per child (between ages six and 17). Families would receive monthly payments, and the payments would begin four months prior to the child’s due date. Romney proposes to pay for the program in part by repealing the state and local tax deduction. The allowance would also phase out at the highest income levels.

The policy is obviously pro-parent. It directly and materially eases the financial burden of child-bearing and child-rearing. A Niskanen Center study estimates that the plan “would reduce U.S. child poverty by roughly one third, and deep child poverty by half.”

I also argued that the plan is functionally pro-life. Since we know at least some abortion decisions are driven by financial concerns, child allowances will likely save lives. In an important piece for Public Discourse, IFS research fellow Lyman Stone agrees. Why? Three reasons. His proposed allowances begin during pregnancy, they “unambiguously improve the tax- and benefit-treatment of marriage,” and “cash transfers directly reduce abortions.”

On the latter point, the research is compelling. Here’s Stone:

Three key academic studies have tested this in interesting natural experiments: one using a child allowance program in Spain, one using a baby bonus in the Friuli-Veneto region of Italy, the other using changes in the enforcement of child support in US states. Both studies found the same thing: when mothers get more financial support for childbearing (whether via a direct cash benefits, as in Spain or Italy, or through more reliable and steady child support checks, as in the US example), they are far less likely to pursue abortion. Indeed, reduced abortions accounted for nearly 20 percent of the resulting increase in births after Spain implemented its baby bonus. In Italy, abortions fell by more than births rose: the entire effect on fertility was through reduced abortions.

More:

I found that when government support per child rises by about 5 percent of GDP per capita (in the United States, this would mean offering a new $3,500 annual child allowance on top of the child tax credit), the share of births plus abortions made up by abortions usually falls by about 1 percentage point. This estimate taken from dozens of countries’ data fits the Spanish case to a T: my model suggests the abortion ratio should have fallen by about 2.3 percentage points in response to how generous Spain’s program was. In reality, it fell by 2.5 percentage points.

These effects may seem small, but in the United States, a one-percentage-point decline in the abortion ratio would imply 40,000 fewer abortions: 40,000 more babies born. This would reduce the number of abortions by nearly 5 percent.

If the increased-immigration policy model conflicts with much of the populist right, the child-allowance proposal conflicts with traditional Republican efforts to tie government benefits to work requirements. I like the way our Morning Dispatch crew distilled the dispute:

Ultimately, the intraparty disagreement boils down to this question: What is the primary aim of the social safety net? Proponents of attaching work requirements to all forms of welfare argue that such programs exist to alleviate the worst effects of poverty while also taking pains to ensure that recipients are first supporting themselves to whatever degree they are able. But proponents of plans like Romney’s argue that family policy in particular should take into account that children are a societal good in and of themselves—even when considered from a bloodless economic perspective—since children are necessary to replenish the stock of future taxpayers.

Also, is there a distinction worth mentioning between “small government” and “limited government”? Child allowances, while expensive, aren’t intrusive. Work requirements, though they limit benefits, require bureaucracies to enforce. Again, let’s go back to the Morning Dispatch:

Factions within the conservative movement disagree on whether the interest of “small government” is served by a frequently confusing and bloated bureaucratic compliance regime set up to ensure that only people who deserve welfare benefits receive them. This distinction was on full display in an American Enterprise Institute (AEI) debate on the child allowance policy that took place Tuesday: AEI’s Scott Winship, who opposes the Romney plan, lamented that caseworkers tend to get a bad rap, while economist Lyman Stone, arguing in favor, took the opposite view. (Both Winship and Stone have written for The Dispatch.)

“The point is that while child allowances may risk expanding the total size of government, they also dramatically reduce the intensity of the intervention of that government,” Stone said. “I don’t think we should act like the median [Temporary Assistance for Needy Families] caseworker is our ally in advancing a conservative social vision. And I think generally the bureaucracy is not an ally to conservatism.”

So, over the long term, what does an increasingly-diverse, immigrant-friendly, child-subsidizing nation look like culturally and politically? The answer might surprise you. I’d urge you to read every sentence of this fascinating David Shor autopsy on the 2020 election and American electoral trends, but the short answer is that a Democratic Party that is increasingly-reliant on an educated, white progressive base may be sowing the seeds of its own destruction. Minority voters are simply more conservative (and far more religious) than white Democrats. This excerpt (with Noah Smith’s assessment) is instructive:

I’ve said this before, and I’ll say it again. There is a blue ocean of possibility for a reasonable (and humane) GOP. But right now at the state level it is busy passing laws that are aimed at placing additional hurdles on voting—hurdles that disproportionately harm black and brown voters. And one of the GOP’s key voting blocs—white Evangelicals—are more likely to support cutting legal immigration by 50 percent (and Trump’s family separation policy) than any other American religious demographic.

In fact, by some measures, white Evangelical support for Trump was driven more by Trump’s support for immigration restrictions than by his opposition to abortion.

We’re in the midst of the GOP civil war. So far it appears that the forces of Trumpian populism are winning, and it doesn’t seem close. But it’s not over yet. Is there a vision for a GOP that welcomes immigrants, embraces parents, celebrates birth, and defends the entire Bill of Rights—by protecting free speech and religious liberty and by protecting vulnerable citizens from unlawful police violence and law enforcement overreach? I honestly don’t know. But I do know that’s the party I’d prefer.

One more thing …

I’m biased, but I think today’s Advisory Opinions podcast was especially good. It’s about the Equality Act, the Voting Rights Act, and the rather interesting emerging dynamics on the Supreme Court. Good times.

One last thing …

I’ve done it. I’ve finally found the folks who are even more excited than me about the progress of the SpaceX Starship program. Here’s the latest launch, complete with a seemingly-successful landing followed by a giant kaboom, cued to a few seconds before ignition. Enjoy the ride and soak in the enthusiasm:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.