In the late summer of 1991 I arrived at Harvard Law School a devout Evangelical, conservative Republican. I grew up in a small town in Kentucky, attended a private Christian college in Nashville, and then walked into an intellectual home for a new theory I’d never encountered: critical race theory.

I remember reading the some of the key early texts, including Kimberle Crenshaw’s seminal law review article, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” first published in 1989. I remember being assigned excerpts from Derrick Bell’s book, Faces At The Bottom Of The Well: The Permanence Of Racism.

I remember being both challenged and frustrated by CRT. There were elements that, even in the moment, were immediately enlightening, such as Crenshaw’s discussion of the inability of contemporary antidiscrimination law to grapple with the nuances of “intersecting” identities.

There were also troubling elements, including a pervasive pessimism about the ability of America’s classical liberal structures to achieve true racial equality and an unwillingness to acknowledge the extent of America’s racial progress. In addition, some of CRT’s most ardent adherents could be remarkably intolerant, sometimes even seeking to shout down competing ideas or suppress dissent.

What I did not think, at any point, was that I was reading an idea fundamentally at odds with orthodox Christianity.

If you wonder why I raise such a thought, you’re not following the grassroots debate about CRT closely enough. You don’t understand the reason for its raw intensity. The Republican attack on CRT isn’t just an attack on an academic idea. At the grassroots it’s seen as a defense of Christianity itself. The origin of this belief, like everything related to CRT, is complicated. But its elements are simple enough to explain.

The process went like this:

First, there was and is an interesting and highly technical academic and theological debate about the compatibility of Christianity and CRT, with a number of voices arguing that CRT clashed with the Christian faith.

Second, the definition of CRT was fundamentally and intentionally changed by conservative activists to encompass an enormous number of arguments and ideas about race, including arguments and ideas that have nothing to do with CRT.

Third, the result is that large numbers of Christians who now hear unfamiliar or unpopular arguments about race not only think those ideas are “CRT” but also that they’re positively unchristian and poisonous to their souls.

Let’s start with the theological debate. The thoughtful Christian argument against CRT boils down to the notion that it’s, in essence, not so much an academic theory as an all-consuming worldview. As Christian writers and scholars Neil Shenvi and Pat Sawyer argued in an important piece in the The Gospel Coalition, critical theory (CRT is one aspect of critical theory)* purports to answer “our most basic questions: Who are we? What is our fundamental problem? What is the solution to that problem? What is our primary moral duty? How should we live?”

The authors contrasted what they described as the “metanarratives” of Christianity and critical theory. Christianity “provides us with an overarching metanarrative that runs from creation to redemption,” whereas “critical theory is associated with a metanarrative that runs from oppression to liberation.”

While the essay doesn’t claim that everything critical theory affirms as false, it asserts that the Christianity and critical theory’s “respective metanarratives will vie for dominance in all areas of life.” How does this work? Shenvi and Sawyer ask us to consider the question of identity: “Is our identity primarily defined in terms of our vertical relationship to God? Or primarily in terms of horizontal power dynamics between groups of people?”

Or consider the question of sin and guilt. Here again Shenvi and Sawyer contrast Christianity with their perception of critical theory: “Is our fundamental problem sin, in which case we all equally stand condemned before a holy God? Or is our fundamental problem oppression, in which case members of dominant groups are tainted by guilt in a way that members of subordinate groups are not?” (Emphasis in the original.)

All of this is nuanced and debatable. Christian defenders of CRT would note, for example, that when you’re talking about oppression, you are talking about sin. And while members of dominant groups don’t have personal guilt for the actions of their ancestors and predecessors, there is a shared responsibility to ameliorate the effects of injustice.

Moreover, biblical commands to “act justly” require us to consider not just our vertical relationship with God but also our horizontal relationships with our neighbors, including those neighbors who face the consequences of systemic sin and oppression. In other words, our vertical relationship with God creates horizontal obligations, and there are ways in which CRT’s historical and legal analyses can help us better understand our nation and our culture.

For example, I’d urge you to read Crenshaw’s law review article with an open mind. She analyzes three employment discrimination cases to make the argument that federal civil rights law should recognize that “black women” can experience discrimination that is distinct from the discrimination experienced by black men and by white women. It’s a fascinating and highly technical legal argument, and it’s hard to even conceive of how it could be unchristian.

But one doesn’t have to get quite as theological as Shenvi and Sawyer to argue about the religious implications of CRT. In an influential 2018 Atlantic article, John McWhorter argued persuasively that elements of secular modern anti-racism (which can often draw on CRT themes and arguments) looked a lot like a religion.

White privilege, he argued, is in this view akin to original sin. “The idea of a someday when America will ‘come to terms with race’ is as vaguely specified a guidepost as Judgment Day.” Declaring speech “problematic” is similar to declaring it heretical or blasphemous. And “virtue signaling” is roughly analogous to an “aggressive display” of faith in Jesus.

I’ve also argued that extreme manifestations of CRT can clash with Christian orthodoxy. There’s a certain irony in CRT. It argues that race is a social construct (a valuable insight and a concept entirely consistent with Christian thought) yet also sometimes places that social construction at the center of individual identity, as the primary lens through which you view your place in the world.

Again, all of this is complicated, and a true critical theorist would read Shenvi, Sawyer, McWhorter, or me and object on any number of points. Indeed, what even is a “true” critical theorist when the concept includes branching lines of thought, with real debate and disagreement between different scholars?

In June 2019, the Southern Baptist Convention, the nation’s largest Protestant denomination, entered the debate. It enacted a common-sense resolution that argued that CRT had uses and limits.

The resolution, called Resolution 9, noted that Evangelical scholars have “employed selective insights from critical race theory and intersectionality to understand multifaceted social dynamics” and that one could gain “truthful insights found in human ideas that do not explicitly emerge from Scripture.”

In other words, CRT had use as an “analytical tool” which could assist in understanding our world, yet that analytical tool is “subordinate to scripture,” and the “gospel of Jesus Christ alone grants the power to change people and society.”

Resolution 9 reflected the ethos of the less fundamentalist branch of the Evangelical movement. This wing of American Christianity is more apt to seek knowledge and insight about the world from secular sources, taking ideas from psychology, sociology, and critical theory to help understand complex cultural, political, and historical questions.

That’s hardly the universal Christian approach, and more fundamentalist Christians have long looked askance at the social sciences (including each discipline above) and are more apt to argue that the solution to the race problem in America is found in the Bible alone.

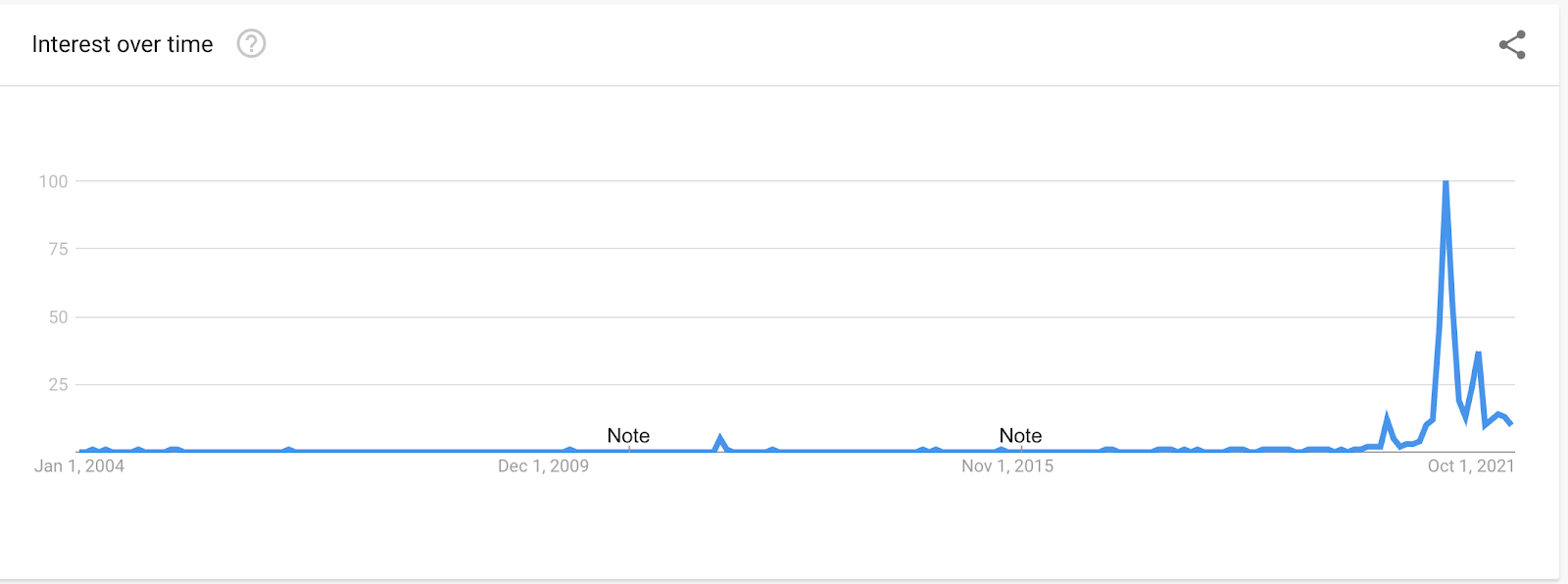

So far, however, everything I’ve explained has been the stuff of panel discussions and competing essays. It’s a niche argument for a relatively niche audience. All that changed last year, however. Last summer CRT became central to the national conversation—with interest spiking far beyond even the days and weeks following George Floyd’s murder and the resulting “national conversation” about race. Google Trends searches of “critical race theory” tell the tale:

So what happened? As with any culturally significant moment, there are multiple explanations. The explosion of interest in CRT is certainly part of the conservative response to the so-called “Great Awokening,” the increasing racial radicalization of white progressives, to the point where white liberals’ perspectives on race moved to the left even of black Democrats.

This radical left turn sometimes veered into the kind of religious intensity that McWhorter identified above. This zeal contained a deeply intolerant strain that manifested in an extraordinary wave of cancellations that alarmed not just conservatives, but many liberals as well.

But conservative alarm wasn’t simply organic. Opportunistic activists like James Lindsay and Manhattan Institute senior fellow Christopher Rufo intentionally and explicitly redefined CRT. Here’s Rufo in a tweet thread with Lindsay:

We have successfully frozen their brand—“critical race theory—into the public conversation and are steadily driving up negative perceptions. We will eventually turn it toxic, as we put all of the various cultural insanities under that brand category. The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think “critical race theory.” We have decodified the term and will recodify it to annex the entire range of cultural constructions that are unpopular with Americans.

He proceeded to be as good as his word, and now the right-wing conversation about CRT is all but useless. Consider, for example, the so-called “anti-CRT” bills that are flooding out of red-state legislatures. They ban ideas that sweep far beyond any reasonable definition of CRT. No critical race theorist worth his or her salt would read Tennessee’s anti-CRT bill and think for a moment that the legislature captured the essence of the theory.

Anti-CRT speech codes are problematic on their own terms, for reasons I’ve explained at length—including that the plain text Tennessee’s law even limits instruction about some of Martin Luther King Jr.’s writings—but the mass-branding of “unpopular” racial ideas as “CRT” has much more pernicious effects when combined with the argument that CRT is unchristian. It closes Christian minds to challenging thoughts and ideas, and it incentivizes a relentless effort within Christian communities to suppress conversations with people who are perceived to be “woke.”

To take one example, Grove City College, a conservative Christian college in Pennsylvania, has endured a storm of controversy over alleged “mission drift.” Hundreds of students, parents, and alumni signed a petition against CRT at the school:

The petition cited as evidence of CRT “asserting itself at GCC” a fall 2020 chapel presentation by Jemar Tisby, a historian and author who writes on race and religion; a chapel that included a pre-recorded TED talk by Bryan Stevenson, an Equal Justice Initiative founder and criminal justice reform advocate; a Resident Assistant training that included the concepts of white privilege and white guilt; and several books used in an education studies class and in focus groups, including Ibram X. Kendi’s “How to be an Antiracist” and Wheaton professor Esau McCaulley’s “Reading While Black.”

The petition makes little sense if one thinks of one role of a college—including a Christian college—as exposing students to competing ideas and theories about race. It makes far more sense if you’re convinced that CRT is a threat to American Christianity. In that context even the very few listed examples of alleged CRT can’t be permitted at the school.

There’s an entire cottage industry of Christian voices who relentlessly police American evangelicalism for evidence of “wokeism” or “CRT,” and the definition of both concepts is almost impossibly broad. Do you believe systemic racism exists? That’s CRT. Do you believe in institutional responsibility to correct the consequences of historic oppression? That’s CRT.

Immense damage is being done. Centuries of American racism warped and distorted our society in countless ways. And while we’ve made tremendous progress in creating a more just society, the effects of slavery and Jim Crow—and the lingering reality of existing racism—present our nation (and the church) with a profound and complicated challenge.

This is the exact wrong time to close Christian hearts and minds to thoughtful voices, including thoughtful voices who offer new approaches to our understandings of race and justice in the United States. You don’t have to agree. You can and should dissent when you sincerely believe ideas are wrong. But when activists shout “CRT” about ideas they don’t like, they’re not defending the faith, they’re often trying to block you from perspectives that Christian believers need to hear.

One more thing …

After an avalanche of thoughtful listener comments about fundamentalism, Curtis and I returned to the topic in this week’s Good Faith podcast. And this time we paid close to attention to how fundamentalism forms. It’s a great discussion about how our human nature can push us towards intolerance, especially when we surround ourselves with people of like mind.

One last thing …

A friend sent this to me, and I thought it was incredibly touching. On the streets of one of the most secular cities in the world, Ukrainian Christians sang a prayer for their country. Their expression of faith and hope inspired me, and I hope it inspires you:

Correction, April 10: I originally identified Shenvi and Sawyer’s Gospel Coalition essay as specifically addressing “CRT.” It addresses “critical theory,” a broader concept that encompasses CRT but also other forms of critical social theories, including theories addressing gender and sexuality. I apologize for the error.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.