One of the first and most elementary things a young Christian learns in Sunday school is the idea that God’s commands are “good for you.” The violation of a moral command activates a set of consequences. On the individual level, this is not a controversial thought. Think of the Ten Commandments—violating prohibitions against adultery, theft, and murder results in pain, chaos, and violence.

Extending beyond the basic requirements of the Decalogue, the Bible is full of if/then propositions that describe the terrible consequences of sin and the benefits of obedience. There are so many, in fact, that it’s one explanation for the persistence of legalism or the prevalence of problematic theologies like the prosperity gospel. Seeking certainty in an uncertain world, Christians latch onto these propositions as if the promised rewards for righteousness are typically immediate, literal, and material.

In fact, there are times when we don’t live to see the benefits of obedience—by “taking up our cross” Christians can in fact die unjust deaths and suffer horrible persecution. I’d urge you to re-read Hebrews 11, the “hall of fame of faith,” to understand how obedience can lead to both earthly triumph and terrible tribulation:

And what more shall I say? For time would fail me to tell of Gideon, Barak, Samson, Jephthah, of David and Samuel and the prophets— who through faith conquered kingdoms, enforced justice, obtained promises, stopped the mouths of lions, quenched the power of fire, escaped the edge of the sword, were made strong out of weakness, became mighty in war, put foreign armies to flight. Women received back their dead by resurrection. Some were tortured, refusing to accept release, so that they might rise again to a better life. Others suffered mocking and flogging, and even chains and imprisonment. They were stoned, they were sawn in two, they were killed with the sword. They went about in skins of sheep and goats, destitute, afflicted, mistreated—of whom the world was not worthy—wandering about in deserts and mountains, and in dens and caves of the earth.

Count me in the category of people who’d rather “put foreign armies to flight” than be “sawn in two,” but that’s not for me to decide.

I digress. The point of this newsletter isn’t to decipher all of God’s promises but rather to note two things at once. First, sin has consequences. Second, sometimes you can see those consequences play out in real time.

Let’s move to Matthew 7:1, one of the most-quoted and least understood verses in the entire Bible. Virtually every American—even the most biblically illiterate—can quote the first two words, “Judge not.” It’s turned into a cultural imperative, repeated in songs, talk shows, gifs, and memes. Don’t judge me.

Why do I say the verse is least understood? Well, for one thing, we have to define “judging.” If I say to a Christian friend who’s having an affair with a colleague that his affair is wrong, I’m not “judging.” I’m simply using basic reading comprehension. God has issued his judgment on adultery, not me. It’s right there in the text.

The larger context provides an if/then construct that is a clear warning of the consequences of uncharitable assessments of others—especially when our own sins are grievous. Here it is:

Judge not, that you be not judged. For with the judgment you pronounce you will be judged, and with the measure you use it will be measured to you. Why do you see the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own eye? Or how can you say to your brother, ‘Let me take the speck out of your eye,’ when there is the log in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your brother’s eye.

The moral command is followed immediately by the consequence—you’ll be judged by the same standards you judge others. Give no grace, receive no grace. We’re extremely familiar with the individual application of this concept. How often do people respond not with sorrow but with a peculiar sense of satisfaction and schadenfreude when, say, a judgmental pastor is caught (literally) with his pants down, or when a vicious public personality is revealed to be a crook or a fraud?

But let’s move beyond the individual. Do the first verses of Matthew 7 describe a reality that isn’t just personal but also cultural and political? Can a nation suffer the consequences of mass-scale intolerance?

I think yes. I think we’re living it right now. And no I don’t think it’s confined to the extremes of “cancel culture” but rather to the way in which ordinary, everyday Americans are increasingly judging their political opponents.

On Thursday, the good folks at Beyond Conflict released a study called “America’s Divided Mind,” and while I’m not sure they had Matthew 7 in mind when they looked at the results, they provided strong evidence of the spiritual consequence of unjust judgment—by the measure we judge others, so shall we be judged.

Its results show why we’re in the grips of toxic polarization and a nonstop state of political emergency. Across the great American political divide, the two warring tribes have made an identical judgment about the other—“I’m not hateful, you are.” Or, to put it even more precisely, “I may not hate you, but you hate me.”

Here’s the summary of the findings:

Large majorities of both Democrats and Republicans substantially exaggerate the extent to which members of the other party dehumanize, dislike, and disagree with them—creating a significant divide between perception and reality.

This means:

The more we feel disliked and dehumanized by members of the other party, the more likely we are to express greater dislike and dehumanization toward them. In this way, the divide between actual and perceived dislike and dehumanization can create a downward spiral of hostility that fuels further toxic polarization.

When you dive into the details, the study gets even more remarkable. With striking regularity, Americans misjudge each other in exactly the same ways.

Let’s take dehumanization—Beyond Conflict asked survey participants to define the extent to which their political opponents were fully evolved, from a scale of 1 to 100. Republicans and Democrats rated themselves highly, in the mid to upper 90s. They rated their opponents almost as highly. “Democrats give Republicans a median score of 83 out of 100, while Republicans give Democrats a median score of 80 out of 100.”

The gap is a bit worrisome, but it hardly represents a cultural emergency. But Beyond Conflict asked a second question. It asked “Democrats and Republicans to guess how evolved members of the other party consider them to be on the same scale.”

The results? Wow:

Republicans and Democrats believe that members of the other party dehumanize them more than twice as much as they actually do. Specifically, Republicans estimate that Democrats rate them at a score of 28 out of 100 (in reality Democrats rated them at an 83). Similarly, Democrats estimate that Republicans rate them at 48 points out of 100 (in reality Republicans rated them at an 80).

No wonder Republicans fell for the Flight 93 rhetoric in 2016. But let’s move beyond the extremes of dehumanization to measuring more mundane “dislike” for your political opponents. Here’s Beyond Conflict on the effects of dislike:

The feeling of being disliked by the other party is a powerful force. Overestimating how much the other party dislikes your party is predictive of higher levels of social distance (e.g., feeling uncomfortable with members of the other party serving as your doctor, being your child’s teacher, or marrying one of your children). At the extreme, misperceptions about dislike can lead to higher levels of support for putting your party’s interests above the country’s in a way that undermines democratic norms.

Here, the findings are alarming on every front. Republicans and Democrats not only actually dislike each other (“When asked how cold (0) or warm (100) they feel about the other party, Republicans give Democrats a score of approximately 34 out of 100, while Democrats give Republicans a score of 28 out of 100”), both sides “feel that the other side dislikes them nearly twice as much as they actually do.”

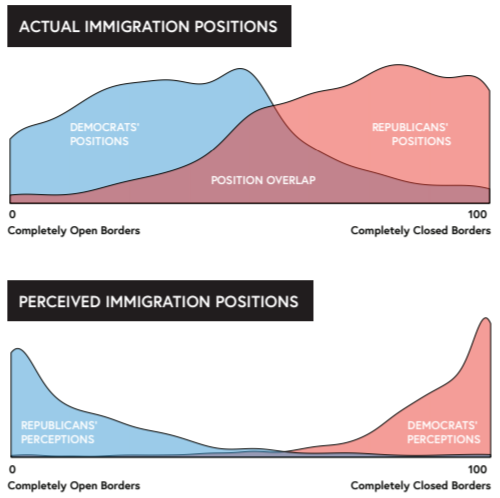

This mutual loathing translates into other misperceptions, such as completely misjudging the extremism of your political opponents. Beyond Conflict looked at the gap between actual and perceived positions in two areas—gun control and immigration. Look at these charts. First, here’s immigration:

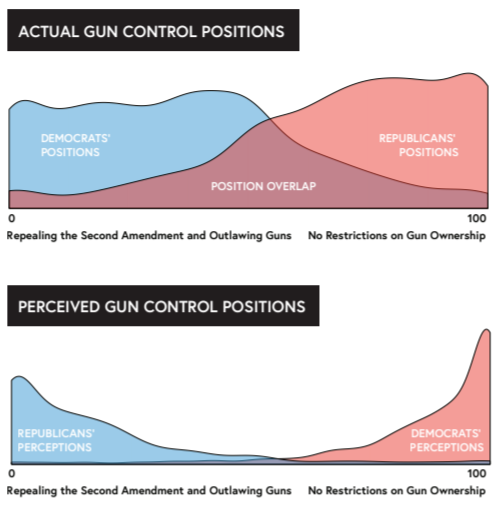

Now, here’s gun control:

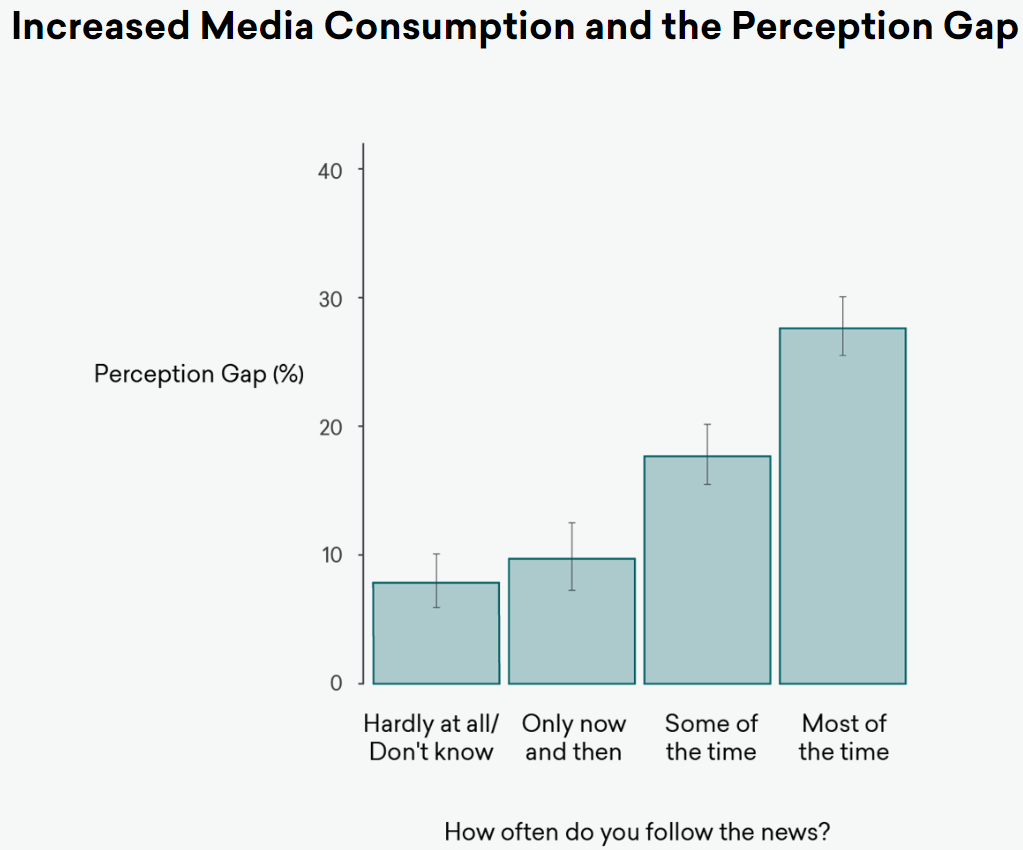

There are differences, but they are not nearly as extreme as we believe. Moreover Beyond Conflict is not the only organization to find this discrepancy. Last year More in Common released a study on the “perception gap” in American politics, finding that Democrats and Republicans were wildly off in their perception of their opponents’ political extremism, and that misperception grew they more news a person consumed:

The most “informed” Americans are leading us astray. They’re the individuals most in the grips of the spiritual law outlined in Matthew 7. As they harshly judge the hatefulness of their political opponents, they are receiving the same judgment in return. As they try to pick out the speck of hate out of their opponents’ eyes, they ignore the plank of misperception in their own.

Longtime readers know that I’m extremely concerned about American polarization. I’ve written an entire book outlining how mutual hatred could cause our nation to divide (pre-order now!) The realities outlined above show the reasons for my alarm. Our sin has consequences.

And yes, believe me, I know that our misjudgments don’t spring from nowhere. Through the magical power of social media, every cancellation, every Karen, every stupid and intolerant comment from any person of any prominence can instantly become a matter of national news, proving what “they” are “really like.”

And the more news you consume, the more Karens and crazies you can quote, so the instant someone asks you why you’re so angry, you can respond, “Did you hear what Shaun King said about Jesus? Have you seen the insanity in the CHAZ? The sins of the few are attributed to the many, and so you say of them all, “You don’t know how bad those people are.”

No, you don’t know how good they are.

In judging our opponents by their worst outliers, we inflict a moral injury on them. We give them grounds to feel aggrieved. We can’t always demonstrate the effects of spiritual laws with charts and graphs (well, maybe we can—consider the documented emotional, economic, and cultural consequences of infidelity and divorce), but that’s how overwhelming our lack of grace has become. That’s how clearly and harshly we misjudge our fellow man.

I’ve said this before, and I’ll say it again. Human beings need forgiveness like we need oxygen. An intolerant nation is a miserable and divided nation. Only grace can light the trail out of the darkness.

One last thing …

Years ago, when I first began listening to Christian music, I bought everything Michael Card published. His music was and is theologically rich, thoughtful, and deeply encouraging. This song, recorded decades ago, is a balm in troubled times:

Photograph by Eduardo Munoz Alvarez/Corbis via Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.