Readers, let me begin with an apology. If you were hoping that today’s French Press would be laden with premium Dr. Seuss content or insightful analysis of the British royal family, I’m sorry. We’re going legal and philosophical today. We’re going to focus on the Biden administration’s effort to reverse one of the Trump administration’s best policies and revive one of the Obama administration’s worst.

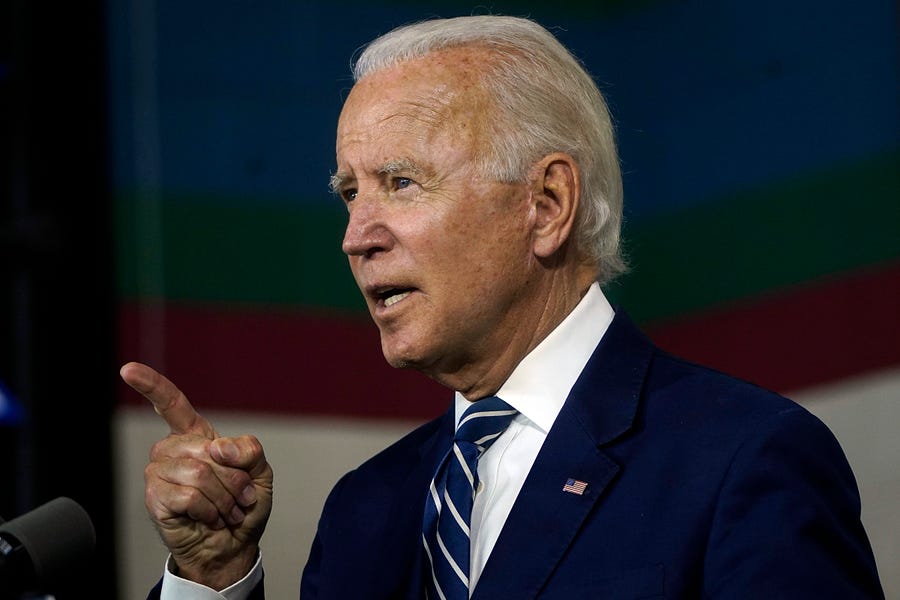

On Tuesday, Biden issued an executive order directing the secretary of education to “consider suspending, revising, or rescinding” Trump administration regulations that guaranteed basic due process protections for accused students in campus sexual misconduct adjudications.

In creating those regulations, the Trump administration had repealed and repudiated a 2011 Obama administration “Dear Colleague” letter that (as I described before) dramatically reduced due process protections for accused students at campuses from coast-to-coast. The administration mandated a low burden of proof (preponderance of the evidence), expanded the definition of sexual misconduct, and failed to preserve for the accused even the most basic right to confront their accuser with cross-examination.

The Obama guidance created a due process nightmare on American campuses. Convinced that too many sexual abusers were escaping accountability for their misconduct, universities implemented streamlined adjudication procedures that sometimes resembled kangaroo courts. I spent years writing piece after piece in National Review highlighting the individual injustices, but to give you a taste of the absurdity, here’s a case I wrote about in 2019:

After a female college student accused her ex-boyfriend of groping her in her sleep, Purdue University conducted an investigation and adjudication so amateurish and biased that it’s frankly difficult to imagine that human adults could believe it was fair or adequate. The plaintiff (John Doe) alleged that he was “not provided with any of the evidence on which decisionmakers relied in determining his guilt and punishment,” his ex-girlfriend didn’t even appear before the hearing committee, he had “no opportunity to cross-examine” his accuser, the committee found his accuser credible even though it did not talk to her in person, the accuser did not even write her own statement or provide a sworn allegation, and the committee did not allow the plaintiff “to present any evidence, including witnesses.”

John Doe sued Purdue, and his case made its way to the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, where the court was singularly unimpressed by the university’s conduct:

[The majority opinion] noted that Purdue’s process, with its permanent, devastating consequences for the student’s career, “fell short of what even a high school must provide to a student facing a days-long suspension.” Withholding evidence from the plaintiff by itself was sufficient to render the process unfair. So was the failure to provide any means of meaningfully examining the accuser’s credibility. As Barrett wrote, the evidence suggests that the committee “decided that John was guilty based on the accusation rather than the evidence.”

And who wrote that majority opinion? The newest member of the Supreme Court, Amy Coney Barrett.

But don’t think for a moment that only conservative judges were appalled at campus procedures. In 2019 California state judges halted more than 70 campus sexual misconduct adjudications to give the California public universities an opportunity to repair their broken procedures. Law professors from across the ideological spectrum condemned the Obama guidance.

So what did the Trump Department of Education do? The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education summed up the regulation nicely. As it noted, the Trump administration required:

-

An express presumption of innocence;

-

live hearings with cross-examination conducted by an advisor of choice, who may be an attorney;

-

sufficient time and information — including access to evidence — to prepare for interviews and a hearing;

-

impartial investigators and decision-makers; [and]

-

a requirement that all relevant evidence receive an objective evaluation.

The regulations also defined “sexual harassment” using a definition provided by the Supreme Court in a case called Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education.

Each of the elements above represents a foundational and basic element of due process. Even in civil proceedings, a plaintiff bears the burden of proof, the defense is entitled to discovery, and defendants enjoy an opportunity to not just cross-examine the plaintiff, but also to cross-examine relevant witnesses.

So why were the Trump reforms controversial? To understand, we have to go back to the reason for the Obama reforms in 2011. At that point, many campus administrators and activists were in the grips of two firm beliefs—that women on campus faced a staggering wave of sexual assaults and that women rarely make false rape reports. The narrative was terrifying. Here’s how I put it in a 2015 analysis of campus rape statistics:

Campus life is [allegedly] so dangerous for women that one in five of them will be victims of sexual assault before they leave college. In other words, there is a fully 20 percent chance that, between the moment a young woman starts freshman orientation and the moment she walks in the graduation line, she’ll become a victim of one of the worst crimes that can be visited upon the human body. This terrible number is buttressed by other numbers — that only 1 percent of assailants are ever arrested, charged, and convicted; that only 4 percent of victims ever report their attack to police or campus security; and that only between 2 and 8 percent of rape reports are false. In other words, for hundreds of thousands of women, the university experience is a nightmare combination of physical assault, indifferent or hostile administrators, and justice denied.

Acting under this impression, campus administrators (and the Obama administration) issued their marching orders: Crack down on campus sex abuse. That meant streamlining adjudications. That meant denying due process. After all, wasn’t there a 90-plus percent chance that the accused was guilty?

But the Obama crackdown suffered from both conceptual and factual flaws. The conceptual flaw is easy to articulate—it’s a simple constitutional reality that no offense is too heinous for due process. Indeed, due process is often more vital when the offense is heinous. It’s the only thing that slows the rush to judgment.

So even if the campus sexual assault statistics were valid, that was no reason to deny due process. Allocate greater resources towards prosecution? Sure. Devote resources to education and safety? Certainly. But deny due process? No.

Moreover, the sexual assault statistics themselves are deeply suspect, and the estimates of false rape claims are worthless. First, the claim that 20 percent of women would be victims of sexual assault in college was based on an online survey of women at two colleges who were given a $10 Amazon gift card for completing the questionnaire. Even with that inducement, the researchers who ran the study noted that response rates were low and warned against drawing sweeping conclusions on the basis of their research:

Although we used the best methodology available to us at the time, there are caveats that make it inappropriate to use the 1-in-5 number in the way it’s being used today, as a baseline or the only statistic when discussing our country’s problem with rape and sexual assault on campus.

Better reporting revealed that campus rape was far less common than feared:

In December 2014, the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics released a report showing that the true incidence of campus rape wasn’t one in five but rather 6.1 per 1,000. Moreover, women are actually safer on campus than off. The “rate of sexual assault was 1.2 times higher for nonstudents.” Critically, the rate of sexual assault has been trending downward since 1997. So when the OCR issued its “Dear Colleague” letter in 2011, it was doing so after a 14-year decline in campus rapes.

But what about the claim that very few rape claims are false? The relevant studies are woefully deficient. In fact, we can never know the percentage of false claims with any degree of certainty. Simply put, our system does not adjudicate whether a claim is true or false. It adjudicates burdens of proof.

Indeed, a close look at one of the principal studies claiming that only a small portion of claims are false illustrates the difficulty in determining the true number. Researchers classified only 5.9 percent of claims as “false,” but they also noted that 44.9 percent of the cases were classified as “case did not proceed.” The category was defined as follows:

This classification was applied if the report of a sexual assault did not result in a referral for prosecution or disciplinary action because of insufficient evidence or because the victim withdrew from the process or was unable to identify the perpetrator or because the victim mislabeled the incident (e.g., gave a truthful account of the incident, but the incident did not meet the legal elements of the crime of sexual assault). (Emphasis added.)

One side effect of flawed studies that purport to determine the “true” rate of false claims is that they create an artificially inflated sense of justice denied. Every student that escapes conviction creates the impression that something went wrong.

We don’t yet know how the Biden administration will choose to revise the Trump regulations. During his campaign he pledged to restore the Obama administration’s 2011 guidance, but he can’t truly rewind the clock. Too many courts in too many jurisdictions have rejected the old regime.

We do know, however, that a sad irony of the Biden plan is that if Joe Biden was a student—and the Obama guidelines he supports applied—Tara Reade’s sexual assault allegation would have likely ended his career. After all, he would have no right to a detailed description of the charges against him, he would have had no ability to discover exculpatory evidence, and he would have enjoyed no right to cross-examine his accuser. (And there would have been no national media applying any independent scrutiny to her claims.)

Betsy DeVos’s decision to protect campus due process was one of the best executive actions of the Trump administration. Its key elements were supported by civil libertarians across the political spectrum. Not everything Trump touched is tainted. Biden should leave this regulation alone.

One more thing …

A number of readers have written to ask my thoughts about H.R. 1, the Democrats’ extraordinarily broad election reform bill. Well, I’ve written about it before, and I stand by my words today:

At its essence, the bill federalizes control over elections to an unprecedented scale, expands government power over political speech, mandates increased disclosures of private citizens’ personal information (down to name and address), places conditions on citizen contact with legislators that inhibits citizens’ freedom of expression, and then places enforcement of most of these measures in the hands of a revamped Federal Election Commission that is far more responsive to presidential influence.

Material elements of the bill violate the Constitution and permit a future version of President Trump to exercise far more control over national elections. You can read the full analysis at the link above. Here’s a little more:

There are parts of the 571-page bill that are worthwhile, but they’re lost in a thicket of unconstitutional federal encroachment over the powers of the states and the rights of citizens. Rather than treating political speech as among the most vital forms of expression in our constitutional republic, the Democratic bill treats it as among the most suspect.

I’m not a fan.

One last thing …

I missed this 60 Minutes report on the Iranian missile attack on the Al Asad airbase, launched in retaliation for the Trump administration’s strike against Qassem Suleimani. It’s a sobering depiction of what it’s like to endure a missile barrage and a reminder that we were very, very fortunate that no American died. Watch it all:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.